Key messages

- In 2018–19, 38% (307,340) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people reported eye or sight problems, and of those, 83% (255,470) wore glasses or contact lenses.

- Based on the 2016 National Eye Health Survey, 10% of Indigenous Australians aged 40 and over were living with vision impairment (not corrected by glasses or contact lenses), and 0.3% were blind.

- Among the estimated 15,000 Indigenous Australians aged 40 and over living with vision impairment or blindness, the most common cause of vision loss were uncorrected refractive error, including long- and short-sightedness (61% of those with vision loss), cataract (20%) and diabetic retinopathy (5.2%).

- In 2018, the prevalence of active trachoma was 3.9% among children aged 5–9 in 120 remote Indigenous communities at risk of endemic trachoma in Qld, WA, SA and the NT.

- In 2018–19, 3.2% (an estimated 26,357) of Indigenous Australians reported having had a sight problem corrected by laser or cataract surgery. The most common condition corrected was cataracts (78% or 20,451).

- The estimated prevalence of active trachoma among children aged 5–9 in at risk communities fell from 14% in 2009 to 3.9% in 2018. From July 2017 to June 2019, there were 9,681 hospitalisations of Indigenous Australians where diseases of the eye and adnexa were recorded as the principal diagnosis – a rate of 6.2 per 1,000 population.

- Hospitalisation rates were higher for Indigenous females than Indigenous males (6.3 compared with 5.3 per 1,000 population).

- In the decade from 2009–10 to 2018–19, the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians for diseases of the eye and adnexa increased by 88% (from 5.6 to 12 per 1,000), compared with by 24% (from 11 to 14 per 1,000) for non-Indigenous Australians.

- A range of factors heighten the risk of poor eye health among Indigenous Australians, including low birthweight, malnutrition, repeated infections, alcohol and tobacco use, high blood pressure and diabetes.

- Indigenous Australian patients are more likely to attend ophthalmology appointments if eye clinic staff employ a sensitive, patient-centred approach to providing encouragement, reminders and patient transport.

Why is it important?

The partial or full loss of vision is the loss of a critical sensory function that has effects across all dimensions of life. Vision loss and eye disease can lead to linguistic, social and learning difficulties and behavioural problems during schooling years, which can then limit opportunities in education, employment and social engagement. Visual impairment can affect health-related quality of life, physical mobility and independent living (Access Economics 2010; George Institute for Global Health 2017; Hsueh et al. 2013) and the family dynamic (Alsehri 2016). It is also found to reduce life expectancy and increase the risk of earlier nursing home placement and death, mainly due to a higher risk of injury and resultant disability (Access Economics 2010; Estevez et al. 2018; Ng et al. 2018; Taylor H et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2003).

Eye diseases and vision problems are the most common long-term health conditions reported by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Around one-third of Indigenous Australians report eye or sight problems (AIHW 2021). Indigenous Australians people experience higher rates of cataract, diabetic retinopathy and trachoma compared with non-Indigenous Australians (Landers et al. 2010; Razavi et al. 2018).

The factors that contribute to poorer eye health for Indigenous Australians are complex and may be related to a range of social and cultural determinants of health (Razavi et al. 2018; Taylor H et al. 2012; The Kirby Institute 2019). Factors contributing to poorer eye health include those that affect health more generally such as age, high blood pressure, obesity, diabetes, low birth weight and malnutrition. These, in turn, are linked to health risks such as diet, and alcohol and tobacco use (AIHW 2021).

There is evidence that Indigenous Australian children, especially those living in remote areas, generally experience less vision loss, blindness and refractive error than non-Indigenous children (Hopkins et al. 2016; SCRGSP 2016; Taylor H et al. 2009). However, this trend reverses by adulthood, with the prevalence of blindness and vision loss higher in Indigenous Australian adults than non-Indigenous adults (Foreman et al. 2016; Taylor H et al. 2010).

Most of the blindness and vision impairment experienced by Indigenous Australians is caused by conditions that are preventable or amenable to treatment—that is, vision loss due to refractive error, cataract and diabetic retinopathy (AIHW 2021). For example, use of glasses and cataract surgery are 2 relatively low-cost, effective interventions for treating the main causes of vision loss.

Blindness from cataract is now rare in non-Indigenous Australians due to a highly effective surgical procedure to remove cataracts but remains a major cause of vision loss among Indigenous Australians (Taylor H. et al. 2015).

Without treatment, diabetic retinopathy can progress to blindness. Although diabetic retinopathy often has no early symptoms, early diagnosis and treatment can prevent up to 98% of vision loss (Taylor H. et al. 2015). The National Health and Medical Research Council recommends that Indigenous Australians with diabetes should have an eye examination at diagnosis and every year thereafter (Australian Diabetes Society 2008).

Australia remains the only developed country with endemic trachoma. Active trachoma among children and trichiasis among adults is still reported in at risk communities (prevalence of active trachoma of >5% in Indigenous children aged 5-9) in Remote and Very remote Indigenous populations, with endemic areas in Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory (The Kirby Institute 2018). Trachoma is associated with living in an arid, dusty environment; poor waste disposal and a high number of flies; lack of hand and face washing; overcrowding and low socio-economic status (National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit 2019). Clean faces have been shown to have a protective effect (Warren & Birrell 2016), but findings for swimming pools in assisting with prevention are inconclusive for eye conditions (Hendrickx et al. 2016). If left untreated, trachoma can cause scarring of the eyelid, which causes eyelashes to turn inwards (trichiasis). This damages the eye and can lead to blindness (The Kirby Institute 2018).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (the Health Plan), released in December 2021, provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. The Health Plan was developed in genuine partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure early intervention across the life course. Vital to manage the development or progression of health conditions over time, early intervention must focus on the conditions with the potential to become serious, but that are preventable and/or easily treatable.

Priority Five and Priority Seven of the Health Plan focus on early intervention and healthy environments which are crucially important to addressing eye health for Indigenous Australians.

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Burden of disease

In 2018, hearing and vision disorders contributed 2.4% (or 5,833 DALY) of the total disease burden for Indigenous Australians – of this, vision disorders accounted for 12% of the total burden. Indigenous females experienced more burden from refractive errors (a type of vision problem that makes it hard to see clearly) than Indigenous males (53% and 47%, respectively). Indigenous females also experienced more burden due to cataract and other lens disorders than males (54% and 46%, respectively). However, this is partly due to more women living to older ages where these eye conditions become more prevalent. The contribution of refractive errors and cataract and other lens disorders to the hearing and vision disease burden increased with age. For those aged 75 and over, this accounted for almost one-third (32%) of the burden due to hearing and vision disorders.

After adjusting for the differences in the age structure between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, the burden due to hearing and vision disorders was 3.3 times as high for Indigenous as for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022).

Data findings

Eye health based on self-reported data

The 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey provides the most recent reported eye health data for all age groups. These data, which are based on self-reporting, showed that 38% (307,340) of Indigenous Australians reported eye or sight problems and of those, 83% (255,470) wore glasses or contact lenses (Table D1.16.3).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians reported eye or sight problems at a slightly lower rate than non-Indigenous Australians in 2018–19 (49% compared with 52%).

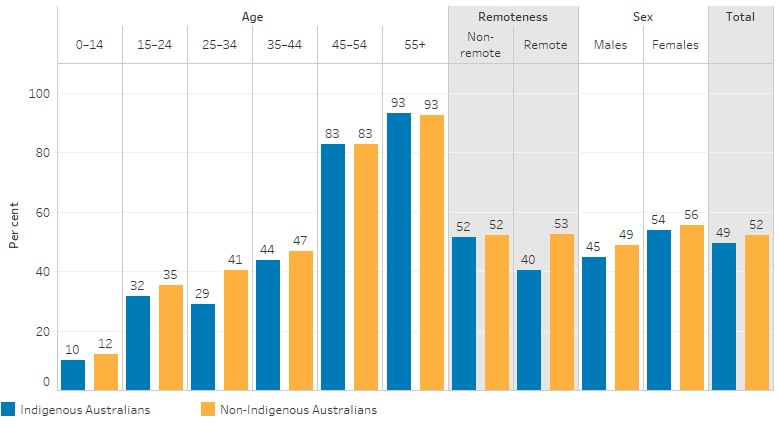

Eye or sight problems for Indigenous Australians increased with age, ranging from 10% for those aged 0–14 to 93% for those aged 55 and over, and rates were lower than for non-Indigenous Australians in age groups under 45.

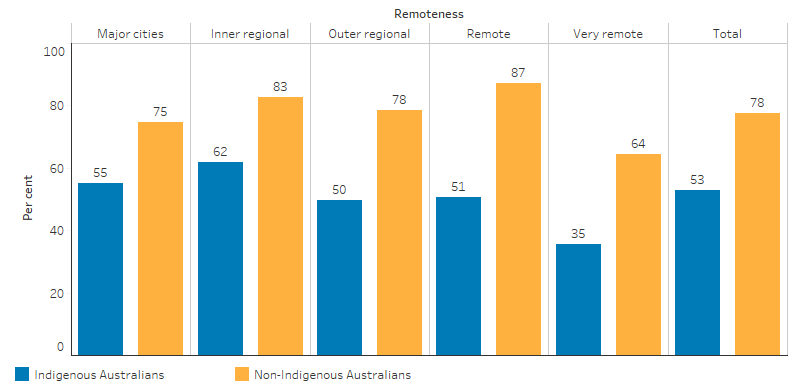

A higher proportion of Indigenous females (54%) than Indigenous males (45%) reported eye or sight problems. Indigenous Australians in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner and Outer regional areas combined) were more likely to report eye or sight problems than those in remote (Remote and Very remote areas combined) areas (52% compared with 40%, respectively) (Table D1.16.6, Figure 1.16.1).

Figure 1.16.1: Age-specific and age-standardised proportion of persons reporting eye/sight problems, by Indigenous status, age, remoteness and sex, 2018–19

Note: Age-specific data is not age-standardised.

Source: Table D1.16.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 and National Health Survey 2017–18.

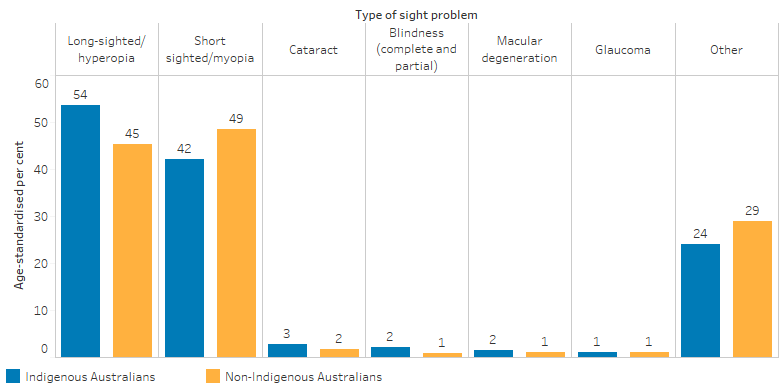

Among Indigenous Australians with eye or sight problems, the most commonly reported were long-sightedness (54% of those with eye or sight problems, age-standardised; an estimated 177,000 people) and short-sightedness (42%; 125,800), followed by cataract (3%; 11,400) and partial or complete blindness (2%; 7,000). Of non-Indigenous Australians reporting eye or sight problems, the most common conditions were short-sightedness (49%, age-standardised), followed by long-sightedness (45%) (Table D1.16.3, Figure 1.16.2).

Figure 1.16.2: Type of eye or sight problems reported among people with an eye or sight problem, by Indigenous status, 2018–19 (age-standardised proportion of those with eye or sight problems)

Notes:

1. ‘Other’ includes other disorders of choroid and retina, presbyopia, astigmatism, other disorders of ocular muscles binocular, other visual disturbances or loss of vision, colour blindness and other diseases of eye and adnexa.

2. Denominator for percentages is the number of people (Indigenous or non-Indigenous, as applicable) with eye or sight problems.

Source: Table D1.16.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 and National Health Survey 2017–18.

Indigenous Australians reported higher rates of partial or complete blindness (2.4 times as high) and cataract (1.6 times as high) than non-Indigenous Australians. Rates for Indigenous Australians were slightly higher for long-sightedness (1.2 times as high) but were slightly lower for short-sightedness than for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.16.3).

Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who had diabetes were 1.7 times as likely to report eye problems (81% or around 53,700 people) as those without diabetes (48% or around 225,600 people) (Table D1.16.7).

Based on self-reported data, among Indigenous Australians of all ages who had diabetes (an estimated 84,157 people), 81% of them had an eye condition in 2018–19 (around 67,900 people). Of Indigenous Australians who had diabetes and an eye condition, 17% reported that the eye condition was due to diabetes (around 11,400 of 67,900 people). Of Indigenous Australians who had diabetes, 48% (around 40,500) had last consulted an eye specialist or optometrist in the previous year (Table D1.16.4).

Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who rated their health as fair/poor were 1.6 times as likely to report eye problems as those rating their health as excellent/very good/good (72% compared with 46%) (Table D1.16.7).

For Indigenous children aged 0–14, 10% were reported to have eye or sight problems in 2018–19 (an estimated 28,100 children), up from 8.8% in 2012–13 (Table 1.16.6) (AHMAC 2017). In 2014–15, treatment was received by 89% (21,200) of Indigenous children with eyesight problems. The most common treatments were glasses or contact lenses (71%; 16,800), and eye checks with specialists (27%; 6,500). A higher proportion (90%; 19,600) of those Indigenous children living in non-remote areas received treatment compared with those in remote areas (68%; 1,420) (Table D1.16.22).

In 2018–19, among Indigenous Australians of all ages, an estimated 3.2% (around 26,400 people) had a sight problem corrected by laser or cataract surgery. Of those who reported eye conditions corrected by laser or cataract surgery, the most common condition corrected among Indigenous Australians was cataracts (78%, or around 20,500 of 26,400 people). The proportion of those who have ever had corrective eye surgery increased with age, 0.1% of those aged 0–24, 1.2% of those aged 25–44, and 13% of those aged 45 and older (Table D1.16.3).

Vision loss in adults based on eye examinations

The 2016 National Eye Health Survey (NEHS) measured eye health in Indigenous Australians aged 40 and over and non-Indigenous Australians aged 50 and over. A younger minimum age was chosen for Indigenous participants due to an earlier onset and more rapid progression of eye diseases (Foreman et al. 2017a). The survey involved a general questionnaire, vision testing, anterior segment examination, visual field testing, fundus photography and intraocular pressure testing.

The results estimated that 399,000 Australians were living with vision impairment or blindness in 2016; this estimate includes 15,000 Indigenous Australians aged 40 and over (Foreman et al. 2017b). For Indigenous participants aged 40 and over, 10% were living with vision impairment, and 0.3% were blind (AIHW 2020). After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the rate of vision loss (including vision impairment and blindness) for Indigenous participants was around 3 times the rate for non-Indigenous participants (Foreman et al. 2017b).

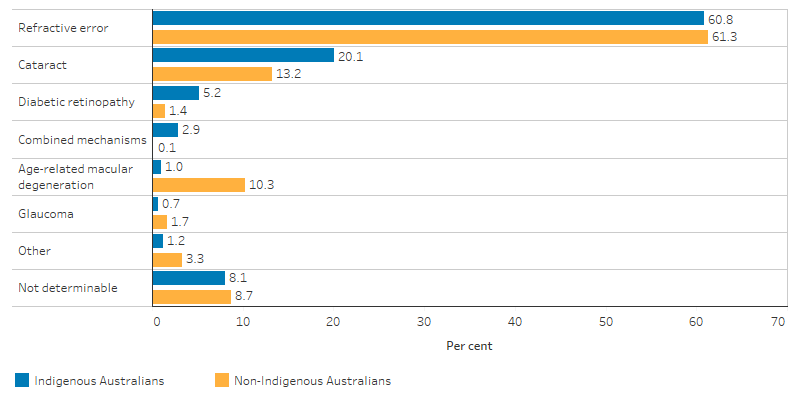

Of those with vision loss, the most common causes for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in the survey were uncorrected refractive error, including long- and short-sightedness (both 61%), cataract (20% and 13%, respectively), diabetic retinopathy (5.2% and 1.4%, respectively), age-related macular degeneration (1% and 10%, respectively) and glaucoma (0.7% and 1.7%, respectively) (AIHW 2020) (Figure 1.16.3).

Figure 1.16.3: Main causes of bilateral vision loss (vision impairment and blindness) for Indigenous adults aged 40 and over and non-Indigenous adults aged 50 and over, by Indigenous status, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey 2016 (AIHW Indigenous eye health measures 2020 report, Figure 2.3).

The major cause of blindness for Indigenous participants over 40 was cataract (40%), while for non-Indigenous adults over 50, the major cause was age-related macular degeneration (71%) (Foreman et al. 2017b).

In 2016, the prevalence of vision loss increased with age for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous participants. The rate of vision loss for Indigenous adults aged 50–59 was 1.6 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians this age, and for those aged 60–69 it was 4 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians the same age (AIHW 2020).

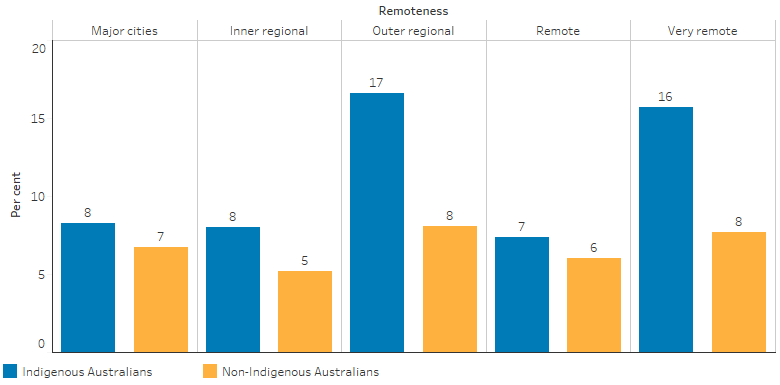

The prevalence of vision loss for Indigenous adults aged 40 and over was highest in Outer regional areas (17%) and Very remote areas (16%), while for non-Indigenous Australians, the rate did not differ significantly by remoteness (AIHW 2019a) (Figure 1.16.4).

Figure 1.16.4: Prevalence of bilateral presenting vision loss, by Indigenous status and remoteness, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey 2016 (AIHW Indigenous eye health measures 2018 report, Table 1.1.1e).

More than half of those with vision loss who were found to have a major eye disease or condition were previously undiagnosed. This amounted to 57% for Indigenous participants and 52% for non-Indigenous participants (AIHW 2019a).

NEHS Indigenous survey participants with reported diabetes had lower rates of recommended diabetes eye checks than non-Indigenous participants (53% compared with 78%), particularly in Very remote areas (35% compared with 64% respectively) (AIHW 2019a) (Figure 1.16.5).

Figure 1.16.5: Proportion of those with diabetes who had an eye examination in the recommended timeframe, by Indigenous status and remoteness, 2016

Source: National Eye Health Survey 2016 (AIHW Indigenous eye health measures 2018 report, Table 2.4.2b).

In 2016, for those who needed cataract surgery, Indigenous adults aged 40 and over had a lower rate of surgery than non-Indigenous adults aged 50 and over, 59% compared with 89%. The treatment rate for refractive error was also lower for Indigenous Australians—82% compared with 94% (AIHW 2019a).

In the 2008 National Indigenous Eye Health Survey (NIEHS), trachoma accounted for 9% of blindness among Indigenous adults, whereas it was not found to be a cause of vision loss or blindness in the 2016 NEHS (Foreman et al. 2016; Taylor et al. 2009). The prevalence of blindness among Indigenous participants reduced between 2008 and 2016, from 1.9% to 0.3%, suggesting a possible improvement in the prevention or treatment of the most severe forms of vision loss. However, these results should be treated with caution, as they are based on small numbers (AIHW 2019a).

Medicare usage

In 2018–19, there were 81,637 Medicare health assessments (which included eye checks) undertaken for Indigenous Australian children aged 0–14, representing 29% of children in this age group. There were also 127,798 health checks undertaken for Indigenous Australians aged 15–54, 28% of those in this age group and around 39,406 for those aged 55 and over, amounting to 40% of adults in this age group (Table D3.04.1).

Trachoma

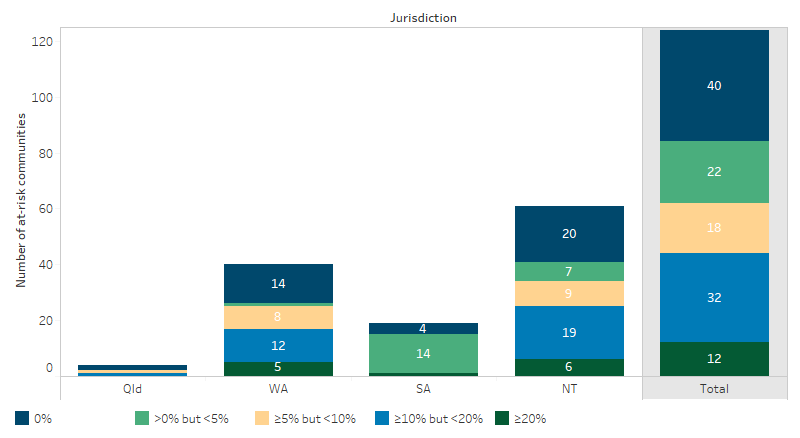

In 2018, the National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit reported on a screening study conducted in 120 remote Indigenous communities at risk of endemic trachoma in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory (National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit 2019). The prevalence of active trachoma among children aged 5–9 in these communities was 3.9% (Figure 1.16.6).

Figure 1.16.6: Number of at-risk communities according to level of trachoma prevalence in children aged 5–9, by jurisdiction, 2018

Note: Includes at-risk communities that did and did not screen in 2018.

Source: National Australian Trachoma Surveillance Report 2018.

Trachoma prevalence was 5.1% in the Northern Territory, 4.6% in Western Australia, 2.8% in Queensland and 0.5% in South Australia. Of the at risk communities in these jurisdictions, 52% had endemic (prevalence above 5% in children aged 5–9) trachoma and 33% had no trachoma detected. Of detected active trachoma cases (144), 100% received treatment. Additional screening was for clean faces, with 73% of children overall having clean faces. Trachoma is no longer considered a public health concern in Queensland (Table D1.16.9)

The estimated prevalence of active trachoma among 5–9 year-olds in at risk communities fell from 14% in 2009 to 4.0% in 2012 and then plateaued to 3.9% in 2018 (AIHW 2019a) (Table D1.16.9).

Eye health managed by general practitioners

The Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health survey (2010–15) showed that eye health problems accounted for 1.1% of all problems managed by general practitioners (GPs) for Indigenous Australian clients. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, this was a rate of 24 per 1,000 encounters for Indigenous Australians, which is similar to the rate for Other Australians (23 per 1,000 encounters) (Other Australians includes non‑Indigenous Australians and those whose Indigenous status is unknown).

Cataract was the leading eye health problem managed by GPs for Indigenous Australians (5.1 per 1,000 encounters). This was 3.5 times the rate as for Other Australians (1.5 per 1,000 encounters) (Table D1.16.11).

Indigenous primary health organisations

In 2017–18, Australian Government‑funded Indigenous primary health care organisations facilitated access to optometrists and ophthalmologists for their clients. Some services were provided at the organisation’s premises, and others were provided offsite. Access to optometrists was provided onsite by 111 organisations (56%), offsite by 50 organisations (25%) and a combination of onsite and offsite by 29 organisations (15%). There was no access provided by eight organisations (4%). Access to ophthalmologists was provided onsite by 39 organisations (20%), offsite by 112 organisations (57%) and a combination of onsite and offsite by 28 organisations (14%). There was no access provided by 19 organisations (10%) (AIHW 2019b).

Eye health and hospitalisation

Between July 2017 and June 2019, there were 9,681 hospitalisations of Indigenous Australians where diseases of the eye and adnexa were recorded as the principal diagnosis (a rate of 5.8 hospitalisations per 1,000 population), accounting for 1.6% of all hospitalisations of Indigenous Australians (excluding dialysis). Hospitalisation rates were higher for Indigenous females than Indigenous males (6.3 compared with 5.3 per 1,000 population, respectively) (Table D1.02.1, Table D1.16.12).

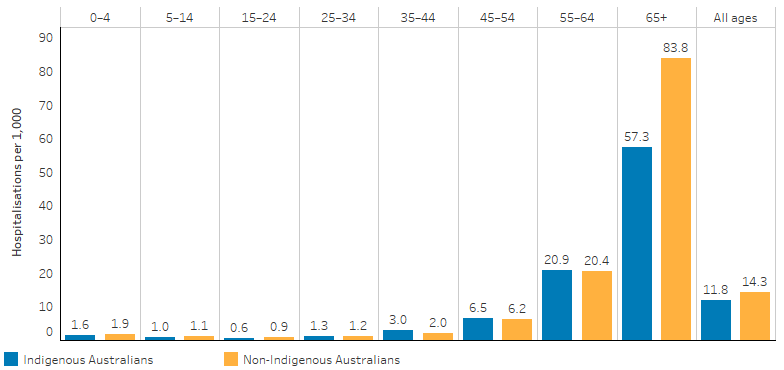

For Indigenous Australians, the hospitalisation rate for diseases of the eye and adnexa increased with age, from 1.3 per 1,000 for those aged 25–34 to 57 per 1,000 for those aged 65 and over. Hospitalisation rates were higher for Indigenous females than males in all age groups over 15–24 of age (Table D1.16.12, Figure 1.16.7).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, the hospitalisation rate for diseases of the eye and adnexa was 21% lower for Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians.

Figure 1.16.7: Hospitalisation rates for diseases of the eye and adnexa (based on principal diagnosis), by Indigenous status and age group, Australia, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Totals are age-standardised.

Source: Table D1.16.12. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

The leading cause of hospitalisations for diseases of the eye and adnexa was disorders of the lens (senile and other cataracts), which accounted for 60% of these hospitalisations (5,826 of 9,681 hospitalisations). This was followed by disorders of the choroid and retina (13% or 1,260) and disorders of the conjunctiva (7.1% or 684) (Table D1.16.15).

The hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians for diseases of the eye and adnexa was nearly three times as high as for those living in the Northern Territory compared with those living in the Australian Capital Territory (6.9 and 2.5 per 1,000 population, respectively). These jurisdictions reflect the highest and lowest rates across all states and territories (Table D1.16.14). Generally, the hospitalisation rate increased as remoteness increased, the exception being for Indigenous Australians living in Very remote areas, where rates were lower than for those living in Remote areas (7.4 compared with 8.6 per 1,000, respectively) (Table D1.16.13).

In 2017–18, cataract surgery was the most common reason for Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for diseases of the eye. The rates were similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (8.3 and 8.9 per 1,000, respectively) (AIHW 2019c). In 2017–18, the median public hospital waiting time for cataract surgery was 123 days for Indigenous patients, compared with 85 days for Other Australians (AIHW 2018a).

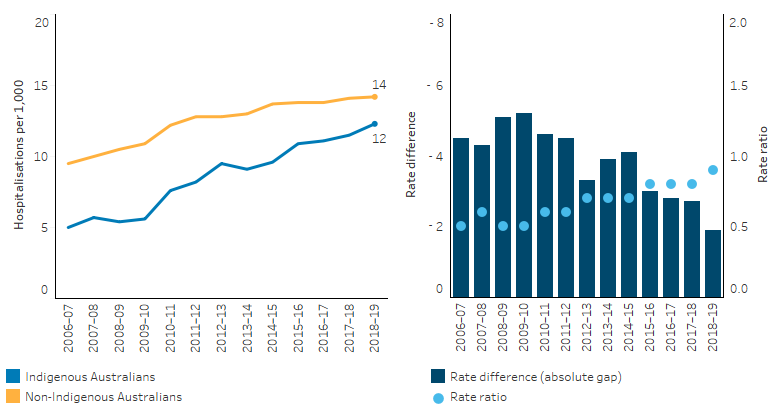

Changes over time

Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians for diseases of the eye and adnexa increased by 88% (from 5.6 to 12 per 1,000), compared with by 24% for non-Indigenous Australians (from 11 to 14 per 1,000) (Table D1.16.18, Figure 1.16.8)

Despite the higher increase in hospitalisation rates for diseases of the eye and adnexa among Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians over time, hospitalisation rates for Indigenous Australians remain lower than non-Indigenous Australians.

Figure 1.16.8: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates and changes in the gap for a principal diagnosis of diseases of the eye and adnexa, by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT combined, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D1.16.18. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Research and evaluation findings

A 2017 review of data from 1,347 Indigenous adults (40 and over) from remote central Australia found that visual impairment in both eyes increased the risk of death by 40% over a 10-year follow-up period, compared with those who were not visually impaired, after adjusting for age, sex, hypertension and diabetes (Ng et al. 2018). Another study of the same cohort also found that diabetic retinopathy was the only specific ocular condition that significantly increased the likelihood of death over the 10 years of follow-up (70% more likely to die when compared with those without visual impairment) (Estevez et al. 2018).

Research shows that over one-third of Indigenous Australian adults report that they had never had an eye examination. A lack of specialist services in rural and remote areas, the complexity of the patient journey, a lack of coordination within and between services, and uncertainty about service providers and the cost of treatment have all been shown to be barriers to accessing eye care (Anjou et al. 2013; Boudville et al. 2013; Taylor H et al. 2012; Turner et al. 2011b). However, Indigenous Australian patients are more likely to attend ophthalmology appointments if eye clinic staff employ a sensitive, patient-centred approach to providing encouragement, reminders and patient transport (Copeland et al. 2017).

Research has found that while diabetic retinopathy screening rates for Indigenous Australians appear to be improving, they remain low compared with non-Indigenous Australians (Keel et al. 2017). Regular eye exams are required to diagnose diabetic retinopathy in the early stages, monitor progression and enable timely referral for treatment (Dirani 2013).

A study published in 2010 from the Eastern Goldfields of Western Australia reported on service-based data collected over 12 years (1995–2007) and emphasised the increasing importance of diabetic retinopathy as a cause of vision loss. The same study found that 75% of Indigenous Australians with vision loss also had diabetes, having diabetes increased the risk of vision loss from any cause by 8.5 times, and 25% of Indigenous Australians with diabetes had signs of diabetic retinopathy (Clark et al. 2010).

A 2015 literature review of diabetic retinopathy screening programs undertaken in urban, rural and remote communities in Australia confirmed that retinal photography screening programs implemented in mainstream and Indigenous communities were highly effective at increasing the number of people who underwent screening for diabetic retinopathy (Tapp et al. 2015).

A study published in 2013 explored the barriers and solutions for the delivery of refractive services among Indigenous Australians. The study collected data from health care providers, policy makers and community members in New South Wales, Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia, Victoria and Western Australia and identified a range of barriers that limited Indigenous Australians’ access to specialist eye care services. Barriers included a poor understanding of eye care and referral processes among primary care practitioners; irregular use of eye charts and vision testing by primary health practitioners resulting in inadequate referral to specialist eye care services; uncertainty about the costs of services and glasses; and confusion about the different providers for eye care services. A barrier identified in remote areas is the need to travel long distances for specialist eye care services. A lack of confidence in the value of the service and inadequate access to culturally safe specialist services were identified as barriers in urban areas (Anjou et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2011c).

A study of cataract procedures conducted in New South Wales between 2001 and 2008 found that compared with non-Indigenous Australians, Indigenous Australians were admitted for cataract surgery at a younger age, were more likely to be a public patient and go to a public hospital, and live in a more disadvantaged or remote area. The researchers suggested that barriers may include inadequate cultural safety in these environments and low levels of private health insurance among Indigenous Australians (NSW Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence 2012).

One study performed nationwide consultations to identify health system barriers that limit access to cataract surgery for Indigenous Australians. Barriers were found to include lack of awareness among health professionals; inadequate knowledge regarding the availability of ophthalmology services; difficulties experienced in making appointments; limited surgical capacity at regional hospitals; poor coordination between hospital, health and eye care services; complexity of the treatment process leading to surgery; inadequate support for patients; costs associated with private ophthalmology consultations and gap fees; long waiting times for public cataract surgery and visiting ophthalmology services; and lack of consistent eye health data for monitoring and evaluation (Kelaher et al. 2012; Razavi et al. 2018).

A 2018 study in Queensland demonstrated that a new cataract surgery pathway led to a dramatic increase in the cataract surgery completion rate, from 1.8% to 45% of Indigenous patients referred for surgery. Staff working on the study and community stakeholders mapped the traditional external cataract surgical pathway; it was then redesigned to reduce the number of patients being removed by the system at key transition points. By integrating the surgical pathway within the local primary health care service, the study showed improved continuity and coordination of care and ensured the sustainability of collaborative partnerships with key external organisations. This led to high-quality outcomes for patients (Penrose et al. 2018). Other studies have recommended appropriate funding models, such as fee-for-service, safety-net or differential funding, in order to incentivise the provision of outreach ophthalmology services in Australia to increase cataract surgery rates, reduce waiting times and lower the costs of attendance (Turner et al. 2011a).

Studies have established the association between trachoma and poor environmental conditions. Factors that contribute to the spread of trachoma include lack of clean water for bathing and general hygiene, dry, dusty conditions, inadequate sewerage facilities, household overcrowding, and high numbers of flies (Cowling et al. 2011; SCRGSP 2011; Taylor H 1997; The Kirby Institute 2015). The regular movement of people between communities is also believed to be an important factor sustaining endemic trachoma in Australia (Shattock et al. 2015).

A 2012 systematic review of the promotion of facial cleanliness for the prevention of active trachoma in endemic communities found that having clean faces when combined with the use of topical antibiotics, reduced the rate of severe active trachoma when compared with topical antibiotic use alone (Ejere et al. 2015).

A 2016 review found that sanitation infrastructure in the community was the critical determinant of facial cleanliness, but face-washing education programs have produced no significant benefits. The review found that the installation of swimming pools in remote Indigenous communities has resulted in a reduction in the prevalence of several common childhood infections. However, the review also noted that there is minimal research on the effect of pools on trachoma rates specifically and that a prospective, controlled trial was needed to test this hypothesis in communities where trachoma is endemic (Warren & Birrell 2016).

A review by Razavi in 2018 showed that the overall gap in vision (a three-fold disparity) has remained unchanged in the eight years between the 2008 NIEHS and 2016 NEHS. However, encouragingly, the prevalence of blindness has reduced over the same time. The review suggested the gap in possession of appropriate spectacles highlights a need for an integrated, well-coordinated and nationally consistent spectacle subsidy scheme for Indigenous Australians. The review also noted the remaining gap in the cataract surgery rate calls for an expansion of existing surgical services, a systems-wide approach for early detection and access to treatment, along with increased investment in comprehensive care pathways for Indigenous Australians with cataract. The review suggested that ongoing priorities to prevent and treat the avoidable vision loss from diabetic retinopathy include improved primary care, health promotion, regular annual screening and timely treatment (Razavi et al. 2018).

A 2017 study further analysing the 2016 NEHS concluded that vision loss is more prevalent in Indigenous Australians than in non-Indigenous Australians, highlighting improvements in eye health care in Indigenous communities are required. The study also confirmed that the leading causes of vision loss were uncorrected refractive error and cataract, which are readily treatable. The study suggested that other countries with Indigenous communities may benefit from conducting similar properly stratified surveys of Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, thereby informing targeted interventions to reduce vision loss in those countries (Foreman et al. 2017b).

The 2019 annual update on the Implementation of The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision (the roadmap) showed that over the last decade, the gap in eye health and vision for Indigenous Australians has halved, and substantial progress has been made towards improving Indigenous eye health and vision. Of the 42 recommendations outlined, 21 have now been fully implemented, and 78% of all activities completed (Taylor H & Anjou 2019).

In 2019, evaluation of the Roadmap commenced to measure the progress and effectiveness of regional approaches to addressing eye care needs for Indigenous Australians since the launch of the Roadmap. The evaluation found evidence of change at both a national and regional level across the country, where Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations are central to this work, and have contributed to improvements in the way services were delivered, and led to increased eye care services (Indigenous Eye Health Unit 2022).

A recent systematic literature review in 2020 described research into non-clinical support for Indigenous eye health, the people who provide such care, and its effects on eye health outcomes. The review found that non-clinical support is critical for facilitating attendance at appointments by patients and ensuring that preventive, primary and tertiary eye care services are accessible to Indigenous Australians (Yashadhana et al. 2020).

A recent review showed that a great deal of progress has been made in improving eye care for Indigenous Australians, but there is still a significant gap in the eye care received and eye health outcomes. The review highlighted that one of the critical areas remaining to be addressed is the provision of access to prompt, culturally safe and affordable cataract surgery. The review recommended that much needs to be done to rectify the long waiting times for both outpatient assessment and cataract surgery in Australia’s public hospitals (Taylor H & Anjou 2020).

The five-year program delivery review of the Victorian Aboriginal Spectacle Subsidy Scheme (VASSS) in 2015 demonstrated the successful implementation of the VASSS for Indigenous Australians. The report showed an increased number of people ordering glasses and accessing eye‐care services, with patient services increasing from 400 to 1,800 per year between 2009 and 2014. The report noted that overcoming the barriers to using eye‐care services by Indigenous Australians can be difficult and resource intensive; however, positive outcomes can be achieved with carefully designed and targeted approaches (Napper et al. 2015).

A 2017 evaluation of the National Trachoma Health Promotion Programme (THPP) was undertaken in six remote Aboriginal communities in Central Australia, to identify community knowledge and perceptions of the THPP and what effects this knowledge had on the respondents and their actions in order to improve and develop future activities and initiatives in trachoma elimination. The evaluation found the level of engagement of community members with the THPP is high, with high levels of recognition, ideas and suggestions that community members provided, and that respondents offered a wealth of comments, indicating that people notice and care about health promotion (Ninti One Limited 2017).

The efficacy of a multi-component health promotion strategy for trachoma was evaluated in 63 Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory. This consisted of health promotion initiatives delivered to 272 health, education and community support staff between 2010 and 2012. The evaluation showed increased trachoma knowledge, attitude and practice among support staff (Lange Fiona D et al. 2017). The study found that trachoma-related knowledge, attitudes and practice increased across all settings and for all primary outcome measures. It concluded that the health promotion strategy for trachoma was associated with increased trachoma knowledge, attitude and practice among health, education and community support staff working with children and in remote Northern Territory communities.

Implications

The factors contributing to the eye health of Indigenous Australians are complex and reflect a combination of broad historical influences, behavioural risk factors (and ensuing chronic disease) and social and cultural determinants. Limited access to primary and other medical care (SCRGSP 2016), sub-standard living conditions, inadequate environmental sanitation and poverty all contribute to the development of eye problems in Indigenous Australian communities (Razavi et al. 2018) and limit opportunities for detection and treatment. Given the modifiable nature of many of these risk factors, efforts to minimise their prevalence will help to reduce eye problems and associated morbidity among Indigenous Australians (Razavi et al. 2018).

Health promotion tools should be culturally appropriate and engaging, created in partnership with Indigenous Australians, and enable people to take preventative action, such as the Trachoma Story Kit (Razavi et al. 2018; Vision 2020) (see Strong Eyes, Strong Communities: Five Year Plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Eye Health and Vision 2019–2024 under Policies and strategies).

The World Health Organization endorses the SAFE Strategy, which has been shown to be an effective tool in reducing blinding trachoma (Lange F et al. 2012). The components of the SAFE strategy are:

- Surgery for trichiasis

- Antibiotics to treat active infection

- Facial cleanliness

- Environmental improvements to sustain reduction of transmission

There are barriers to the uptake of the ‘F’ and ‘E’ aspects of the strategy as they involve behaviour change, sanitation measures and environmental hygiene promotion which are generally outside the role of the health care system (Wright et al. 2010). In addition, a lack of educational and promotional resources and standardised teaching about trachoma has been observed in Australia (Wright et al. 2010). Research has found that local service providers were best placed to inform and liaise within the community and obtain consent; they had the best access to population data, and were able to tailor an intervention that would be appropriate to their community. However, these locally driven programs were unlikely to succeed without support from governments and resources being in place. More evidence is needed about what prevention strategies and interventions are effective in reducing Indigenous eye health problems (Warren & Birrell 2016). Further rigorous evaluation is needed to enable a better understanding of the effectiveness and sustainability of eye health prevention strategies and intervention programs among Indigenous Australians (Warren & Birrell 2016).

It has been estimated that 94% of vision loss among Indigenous Australians is preventable or treatable, and much of it can be rapidly reversed. However, despite higher rates of eye conditions, research consistently shows that Indigenous Australians use eye health services at lower rates, with 35% of Indigenous adults having never had an eye exam (Taylor H. et al. 2015; Turner et al. 2011c). Barriers to accessing eye care include a lack of specialist services in rural and remote areas, the complexity of the patient journey, a lack of coordination within and between services, and uncertainty about service providers and the cost of treatment (Anjou et al. 2013; Boudville et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2011b).

A number of new initiatives have been implemented successfully in recent years that can assist with the costs and management of Indigenous eye health, including the Medicare item for retinal screening, and eye health outreach services. In addition, the Australian Government has been working with Vision 2020 Australia to encourage State and Territory Governments to enhance their existing arrangements for subsidising the cost of spectacles for Indigenous Australians, to help achieve equity of access and a more consistent approach to spectacle subsidies.

Between 2008 and 2016, some measures of Indigenous eye health showed improvement, including the prevalence of blindness and glasses coverage rates. The estimated prevalence of active trachoma among 5–9 year-olds in at risk communities fell from 14.9% in 2009 to 4.0% in 2012 and then plateaued to 3.9% in 2018. However, significant gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians remain, including lower cataract surgery rates and coverage, and longer waiting times for surgery (AIHW 2018; Foreman et al. 2017a; Randall et al. 2014). This is despite Australian guidelines for the monitoring and improvement of waiting times for cataract surgery for Indigenous Australian patients (Boudville et al. 2013). This suggests that health services and hospitals are not yet meeting the need for treating eye problems for Indigenous Australians (Razavi et al. 2018).

The disparity in cataract surgery rates is likely to represent the heterogeneous, ‘patchwork’ provision of cataract surgical services and funding models in regional Australia, which differ at the state, regional and local levels (Turner et al. 2011c).

A strategy for reducing diabetic retinopathy could be to ensure that patients with diabetes undergo the recommended annual diabetic retinopathy eye screening and receive timely treatment. As suggested in a 2015 study, an effective national diabetic retinopathy screening program could address the discrepancy in adherence with screening guidelines and capture up to three-quarters of treatable eye diseases in Indigenous patients (Tapp et al. 2015).

The emerging role of telehealth technology may cost-effectively increase the access to and coverage of diabetic retinopathy screening in the future. As well as retinal cameras and smartphones, newer technology such as optical coherence tomography may have a role in remote diabetic retinopathy screening in future (O'Halloran & Turner 2018).

It is important to develop a better understanding of the various barriers to accessing eye health services, eye examinations, cataract surgery and diabetic retinopathy screening. As data improve, better analysis of gaps in eye health arrangements will be possible to inform programs and policies, to reduce the high proportion of Indigenous vision loss that is preventable or treatable.

To continue to improve Indigenous eye health outcomes, there is a need for a ‘whole-of-system’ approach that includes prevention activities and an integrated and coordinated pathway through primary, secondary and tertiary care, with a capable and culturally competent workforce.

Research has highlighted the need for culturally appropriate and accessible eye care services across all levels of the patient journey (Taylor H & Stanford 2011); the appointment of recognised positions; training and support for eye health workers; the integration of eye care within primary health care and Aboriginal health services (Boudville et al. 2013); and the integration of chronic disease programs and diabetic eye care.

Strong regional and local partnerships that support active collaboration between Indigenous communities and service providers are critical to plan, deliver and improve eye care. Embedding eye care into community-controlled and mainstream services (while enhancing cultural safety in mainstream services), are other vital elements to help ensure that the eye health needs of all Indigenous Australians can be met (Vision 2020).

Priority Five of the Health Plan focuses on early intervention approaches that are accessible to Indigenous Australians and provide timely, high quality, effective, culturally safe and responsive care. This includes an emphasis on place-based approaches that are locally determined. The Health Plan recognises that for some communities a focus on preventing avoidable blindness through the diagnosis and management of eye conditions such as trachoma will be an important priority.

Priority Seven focuses on healthy environments recognising that appropriately sized and functioning homes are important for preventing and controlling illnesses such as trachoma, otitis media and acute rheumatic fever.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

Access Economics 2010. Clear focus: the economic impact of vision loss in Australia in 2009. Melbourne Victoria: Vision 2020 Australia.

-

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2017. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2017. Canberra: AHMAC.

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Indigenous eye health measures 2017. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2019a. Indigenous eye health measures 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2019b. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report — key results 2017–18. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2020. Indigenous eye health measures 2020. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2021. Indigenous eye health measures 2021. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2022. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

-

Alsehri F 2016. Impacts of visual impairment on quality of life and family functioning in adult population. International Journal of Biomedical Research 7.

-

Anjou MD, Boudville AI & Taylor HR 2013. Correcting Indigenous Australians' refractive error and presbyopia. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 41:320-8.

-

Australian Diabetes Society 2008. Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Retinopathy. Canberra: NHMRC.

-

Boudville AI, Anjou MD & Taylor HR 2013. Indigenous access to cataract surgery: an assessment of the barriers and solutions within the Australian health system. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 41:148-54.

-

Clark A, Morgan WH, Kain S, Farah H, Armstrong K, Preen D et al. 2010. Diabetic retinopathy and the major causes of vision loss in Aboriginals from remote Western Australia. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 38:475-82.

-

Copeland S, Muir J & Turner A 2017. Understanding Indigenous patient attendance: a qualitative study. Australian Journal of Rural Health 25:268-74.

-

Cowling CS, Liu BC, Ward JS, Snelling TL, Kaldor JM & Wilson DP 2011. Australian Trachoma Surveillance Annual Report, 2010 Sydney.

-

Dirani M 2013. Out of sight: A report into diabetic eye disease in Australia. Melbourne.

-

Ejere HO, Alhassan MB & Rabiu M 2015. Face washing promotion for preventing active trachoma. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 18.

-

Estevez J, Kaidonis G, Henderson T, Craig JE & Landers J 2018. Association of disease‐specific causes of visual impairment and 10‐year mortality amongst Indigenous Australians: the Central Australian Ocular Health Study. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 46:18-24.

-

Foreman J, Keel S, Xie J, van Wijngaarden P, Crowston J, Taylor H et al. 2016. The National Eye Health Survey 2016: Full report of the first national survey to determine the prevalence and major causes of vision impairment and blindness in Australia. Melbourne: CERA.

-

Foreman J, Xie J, Keel S, van Wijngaarden P, Crowston J, Taylor H et al. 2017a. Cataract surgery coverage rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians: the National Eye Health Survey. The Medical Journal of Australia 207:256-61.

-

Foreman J, Xie J, Keel S, van Wijngaarden P, Sandhu SS, Ang GS et al. 2017b. The Prevalence and Causes of Vision Loss in Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians; The National Eye Health Survey. Ophthalmology.

-

George Institute for Global Health 2017. Low vision, quality of life and independence: a review of the evidence on aids and technologies. Sydney.

-

Hendrickx D, Stephen A, Lehmann D, Silva D, Boelaert M, Carapetis J et al. 2016. A systematic review of the evidence that swimming pools improve health and wellbeing in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40:30-6.

-

Hopkins S, Sampson GP, Hendicott PL & Wood JM 2016. A Visual Profile of Queensland Indigenous Children. Optometry & Vision Science 93:251-8.

-

Hsueh Ys, Brando A, Dunt D, Anjou MD, Boudville A & Taylor H 2013. Cost of close the gap for vision of Indigenous Australians: On estimating the extra resources required. Australian Journal of Rural Health 21:329-35.

-

Indigenous Eye Health Unit 2022. Evaluating the progress and effectiveness of regional implementation of The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision.

-

Keel S, Xie J, Foreman J, Van Wijngaarden P, Taylor H & Dirani M 2017. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Australian adults with self-reported diabetes: the National Eye Health survey. Ophthalmology 124:977-84.

-

Kelaher M, Ferdinand A & Taylor H 2012. Access to eye health services among indigenous Australians: an area level analysis. BMC ophthalmology 12:51.

-

Landers J, Henderson T & Craig J 2010. Central Australian Ocular Health Study: design and baseline description of participants. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 38:375-80.

-

Lange F, Baunach B, McKenzie R & Taylor H 2012. Trachoma elimination in remote Indigenous Northern Territory communities: baseline health-promotion study. Australian journal of primary health 20:34-40.

-

Lange FD, Jones K, Ritte R, Brown HE & Taylor HR 2017. The impact of health promotion on trachoma knowledge, attitudes and practice (KAP) of staff in three work settings in remote Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 11:e0005503.

-

Napper G, Fricke T, Anjou MD & Jackson AJ 2015. Breaking down barriers to eye care for Indigenous people: a new scheme for delivery of eye care in Victoria. Clinical & Experimental Optometry 98:430-4.

-

National Trachoma Surveillance and Reporting Unit 2019. Australian Trachoma Surveillance Report 2018. Sydney.

-

Ng SK, Kahawita S, Andrew NH, Henderson T, Craig JE & Landers J 2018. Association of visual impairment and all-cause 10-year mortality among Indigenous Australian individuals within central Australia: the central Australian ocular health study. JAMA ophthalmology 136:534-7.

-

Ninti One Limited 2017. Evaluation of the National Trachoma Health Promotion Programme. Alice Springs.

-

NSW Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence 2012. The health of Aboriginal people of NSW: Report of the chief health officer. Sydney.

-

O'Halloran RA & Turner AW 2018. Evaluating the impact of optical coherence tomography in diabetic retinopathy screening for an aboriginal population. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 46:116-21.

-

Penrose L, Roe Y, Johnson NA & James EL 2018. Process redesign of a surgical pathway improves access to cataract surgery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in South East Queensland. Australian journal of primary health 24:135-40.

-

Randall DA, Reinten T, Maher L, Lujic S, Stewart J, Keay L et al. 2014. Disparities in cataract surgery between Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal people in New South Wales, Australia. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 42:629-36.

-

Razavi H, Burrow S & Trzesinski A 2018. Review of eye health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra.

-

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2011. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: key indicators 2011. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

-

SCRGSP 2016. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: Key indicators 2016. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

-

Shattock AJ, Gambhir M, Taylor HR, Cowling CS, Kaldor JM & Wilson DP 2015. Control of trachoma in Australia: a model based evaluation of current interventions. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 9:e0003474.

-

Tapp RJ, Boudville AI, Abouzeid M, Anjou MD & Taylor HR 2015. Impact of diabetes on eye care service needs: the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 43:540-3.

-

Taylor H 1997. Eye Health in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

-

Taylor H, Anjou M, Boudville A & McNeil R 2012. The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision: Full Report. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit, School of Population and Global Health, The University of Melbourne; 2012.

-

Taylor H & Anjou MD 2019. 2019 Annual Update on the Implementation of The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision. Melbourne.

-

Taylor H & Anjou MD 2020. Cataract surgery and Indigenous eye care: A review. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology.

-

Taylor H, Anjou MD, Boudville AI & McNeil RJ 2015. The Roadmap to Close the Gap for Vision: Summary Report. Melbourne: Indigenous Eye Health Unit.

-

Taylor H, Keeffe J, Arnold A, Dunn R, Fox S, Goujon N et al. 2009. National Indigenous Eye Health Survey − minum barreng (tracking eyes): Summary report. Indigenous Eye Health Unit, Melbourne School of Population Health, Centre for Eye Research Australia and the Vision CRC: Melbourne.

-

Taylor H & Stanford EE 2011. Coordination is the key to the efficient delivery of eye care services in Indigenous communities. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 39:186-8.

-

Taylor H, Xie J, Fox S, Dunn RA, Arnold AL & Keeffe JE 2010. The prevalence and causes of vision loss in Indigenous Australians: the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Medical Journal of Australia 192:312-8.

-

The Kirby Institute 2015. Australian trachoma surveillance report 2014. Sydney NSW 2502: University of NSW.

-

The Kirby Institute 2018. Australian trachoma surveillance report 2017. Sydney NSW 2502: University of NSW.

-

The Kirby Institute 2019. Australian trachoma surveillance report 2019. Sydney NSW 2052: University of NSW.

-

Turner AW, Mulholland W & Taylor HR 2011a. Funding models for outreach ophthalmology services. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 39:350-7.

-

Turner AW, Mulholland WJ & Taylor HR 2011b. Coordination of outreach eye services in remote Australia. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 39:344-9.

-

Turner AW, Xie J, Arnold AL, Dunn RA & Taylor HR 2011c. Eye health service access and utilization in the National Indigenous Eye Health Survey. Clinical & experimental ophthalmology 39:598-603.

-

Vision 2020. Strong eyes, strong communities: a five year plan for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander eye health and vision 2019-2024. Melbourne.

-

Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Cumming RG & Smith W 2003. Visual impairment and nursing home placement in older Australians: the Blue Mountains Eye Study. Ophthalmic epidemiology 10:3-13.

-

Warren JM & Birrell AL 2016. Trachoma in remote Indigenous Australia: a review and public health perspective. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40 Suppl 1:S48-52.

-

Wright H, Keeffe J & Taylor R 2010. Barriers to the Implementation of the SAFE Strategy to Combat Hyperendemic Trachoma in Australia. Ophthalmic epidemiology 17:349-59.

-

Yashadhana A, Lee L, Massie J & Burnett A 2020. Non‐clinical eye care support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a systematic review. Medical Journal of Australia 212:222-8.