Key messages

- Around 31% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian adults with high/very high levels of psychological distress had visited a health professional about their distress in the four weeks prior to the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (around 45,800 adults)

- In 2020–21, Australian Government-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations employed 551 full-time equivalent social and emotional wellbeing staff and provided 268,529 client contacts for social and emotional wellbeing, the majority of which were for Indigenous clients (86% or 229,968 people).

- From July 2017 to June 2019, there were 3,258 ambulatory-equivalent hospitalisations (comparable to care provided by community mental health-care services) that involved specialised psychiatric care for Indigenous Australians (a rate of 2.0 per 1,000 population).

- Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, there was a 52% increase in the hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians due to mental health-related conditions (from 19 to 29 per 1,000 hospitalisations). The rate of hospitalisation for mental health-related conditions increased by 58% for Indigenous females and by 46% for Indigenous males.

- In 2015–16, Indigenous Australians were 4.3 times as likely to have utilised the Access to Allied Psychological Services program than non-Indigenous Australians.

- Indigenous Australians were 67% as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have claimed through Medicare for psychologist care (144 compared with 215 per 1,000 population) and 58% as likely for psychiatric care (56 compared with 96 per 1,000 population).

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience a higher rate of mental health issues than non-Indigenous Australians with deaths from suicide almost twice as high; hospitalisation rates for intentional self-harm 3 times as high; and a rate of high/very high psychological distress 2.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (see measure 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing). While Indigenous Australians use some mental health services at higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians, it is difficult to assess whether this use is as high as the underlying need. Leading Indigenous mental health researchers and advocates maintain that mental health care for Indigenous Australians remains inadequate and inequitable (Dudgeon et al. 2020).

Social, historical and economic disadvantage contribute to the high rates of physical and mental health problems, adult mortality, suicide, child removals and incarceration, which in turn lead to higher rates of grief, loss and trauma (see measure 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing). Most mental health services address mental health conditions once they have emerged rather than addressing the underlying causes of distress, using a clinical approach that treats rather than prevents. Even so, early access to effective services can help diminish the effects of these problems and help restore people’s emotional and social wellbeing (World Health Organization 2022).

Mental health care may be provided by specialised mental health care services (for example private psychiatrists, and specialised hospital, residential or community services), or by general health care services that supply mental health-related care (for example general practitioners (GPs) and Indigenous primary health care organisations).

The social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and are mostly responsible for health inequalities (WHO 2020). The causes of inequality have been identified as unequal access to health care, schools and education, conditions of work and leisure, housing, and the associated chances of leading a healthy life (Australian Psychological Society 2018). The causes of this inequality are due to the structural disadvantage brought about by social policy, economic systems and the distribution of power and resources. Social determinants of health also have substantial effects on mental health and social and emotional wellbeing. People with a mental health illness are more likely to have experienced disadvantage and be on a low income, with many living in poverty. In these circumstances, people are not only more likely to experience mental illness but are also less likely to be able to access mental health support services due to their situation.

In July 2020, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) identified the importance of enjoying high levels of social and emotional wellbeing. The target for this outcome is to see a significant and sustained reduction in the suicide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people towards zero.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (the Health Plan), released in December 2021, provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement. Priority 6 of the Health Plan focuses on ‘Social and emotional wellbeing and trauma-aware, healing-informed approaches’ to service delivery. Priority 10 of the Health Plan focuses on mental health and suicide prevention.

The Health Plan and the National Agreement are discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

Based on the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, around 31% of Indigenous Australian adults with high/very high levels of psychological distress had visited a health professional about their feelings in the previous four weeks (around 45,800 adults).

The rate was higher for Indigenous females (33%; 29,025) compared with Indigenous males (28%; 16,865), and for those living in non-remote areas (31%; 38,565) compared with remote areas (27%; 6,933) (Table D3.10.1).

In 2017–18, 10.6% (82,847) of Indigenous Australians accessed Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) subsidised clinical mental health-care services (that is, consultant psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, GPs and allied health professionals), as did 10.5% of non-Indigenous Australians (SCRGSP 2020).

In 2018–19, the proportion of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians aged under 25 years who accessed MBS-subsidised primary mental health-care services (that is, clinical psychologists, GPs and allied health professionals) was roughly the same (8.5% and 8.6%, respectively). In Victoria, Indigenous Australians aged under 25 years were 1.4 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have contact with these services (13.5% compared with 9.5%). In comparison, in the Northern Territory, they were half as likely to do so (1.9% compared with 4.1%) (SCRGSP 2020).

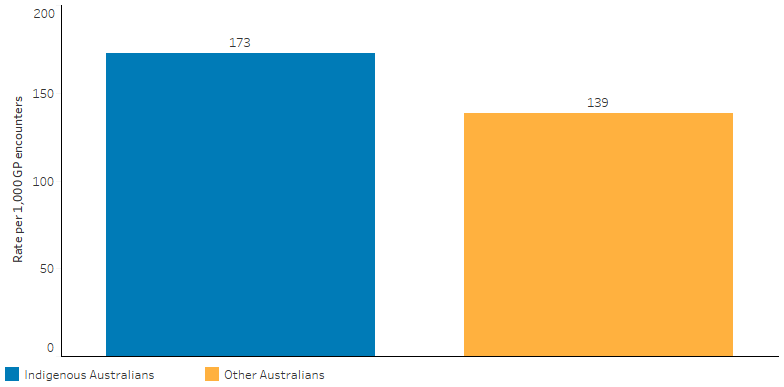

Based on the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (April 2010–March 2015) survey data, 11% of all problems managed by GPs among Indigenous patients were related to mental health. Depression (47 per 1,000 encounters) and anxiety (23 per 1,000 encounters) were the main mental health-related problems managed. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, GPs managed mental health problems for Indigenous Australians at 1.2 times the rate for other Australians (Table D1.18.21, Figure 3.10.1). (Other Australians includes non‑Indigenous Australians and those whose Indigenous status is unknown.)

Figure 3.10.1: Age-standardised rate of mental health-related problems managed by general practitioners, by Indigenous status of the patient, April 2010–March 2015

Source: Table D1.18.21. Analysis of BEACH data by the Family Medicine Research Centre.

Indigenous primary health-care organisations

In 2020–21, there were 191 Australian Government-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations who reported to the Online Services Report Data Collection. These organisations employed 551 full-time equivalent social and emotional wellbeing staff, provided 268,529 client contacts for social and emotional wellbeing, the majority of which were for Indigenous clients (86% or 229,968 people) (AIHW 2022a).

Data for the types of health promotion programs and activities provided by these organisations was available for 2017–18. In 2017–18, 55% (108) of the 198 Indigenous-specific primary health care organisations provided mental health promotion activities (Table D3.03.9). Of the 198 organisations, 89% (177) provided clients access (onsite, offsite, or both) to a psychiatrist, while 94% (187) provided access to a psychologist (AIHW 2019).

More detailed data for social and emotional wellbeing services offered through Indigenous primary health-care organisations was available for 2016–17. In this period, the most common issues related to social and emotional wellbeing managed in terms of staff time and organisational resources were depression (77%), anxiety and stress (76%), grief and loss issues (64%), family and community violence (60%) and family and relationship issues (57%) (AIHW 2018).

In 2016–17, there were 88 organisations funded by the Commonwealth to provide care on social and emotional wellbeing or Link Up counselling services to Indigenous Australians (72 of these were also funded for primary health care and are included above). Eight of these organisations provided Link Up services that assist clients with family tracing and provides reunion support. Within these organisations, 189 counsellors provided 77,068 client contacts to 16,324 clients (an average of 4–5 contacts for each client) (AIHW 2018).

Community and residential mental health services

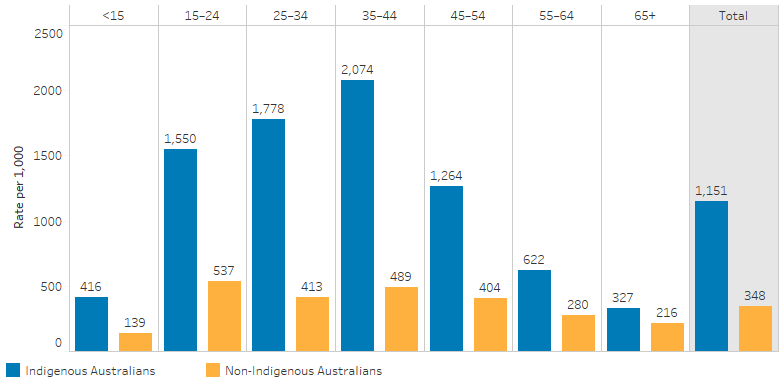

In 2017–18, state and territory-based specialised community mental health services reported approximately 902,900 service contacts for Indigenous clients (10% of service contacts). The rate for Indigenous Australians was 3.3 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians and was higher across all age groups, particularly those aged 25–44 years (Table D3.10.3, Figure 3.10.2).

Figure 3.10.2: Community mental health care service contact rates, by Indigenous status and age group, 2017–18

Note: Totals are age-standardised.

Source: Table D3.10.3. AIHW analysis of National Community Mental Health Care Database.

The community mental health care contact rate for Indigenous Australians was highest in the Australian Capital Territory (2,688 per 1,000 population) and lowest in Tasmania (360 per 1,000population). In New South Wales, the rate for Indigenous Australians was 3.9 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (1,385 and 358 per 1,000 population, respectively) (Table D3.10.4). By remoteness, the rate for Indigenous Australians was highest in Major cities (1,312 per 1,000 population), and lowest in Very remote areas (523 per 1,000 population). In Major cities, the rate for Indigenous Australians was 3.9 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (333 per 1,000 population) (Table D3.10.11).

The rate of residential mental health care episodes in the same period was 6.4 per 10,000 population for Indigenous Australians—2.1 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (3.0 per 10,000 population) (Table D3.10.5).

In 2017, for clinical psychologists, there were 32 full-time equivalent staff per 100,000 people in Remote and Very remote areas combined compared with 105 per 100,000 people in Major cities (Table D3.22.19).

In 2017–18, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 67% as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to have claimed through Medicare for psychologist care (144 compared with 215 per 1,000 population). As was the case for psychiatric care (58% as likely, 56 compared with 96 per 1,000 population) (Table D3.10.2).

In 2015–16, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 4.3 times as likely to have utilised the Access to Allied Psychological Services program than non-Indigenous Australians (826 compared with 193 per 1,000 population) (AIHW 2020).

Hospitalisation

From July 2017 to June 2019, there were 47,096 hospitalisations (or 4.3 % of all hospitalisations) for Indigenous Australians with a principal diagnosis of mental health-related conditions.

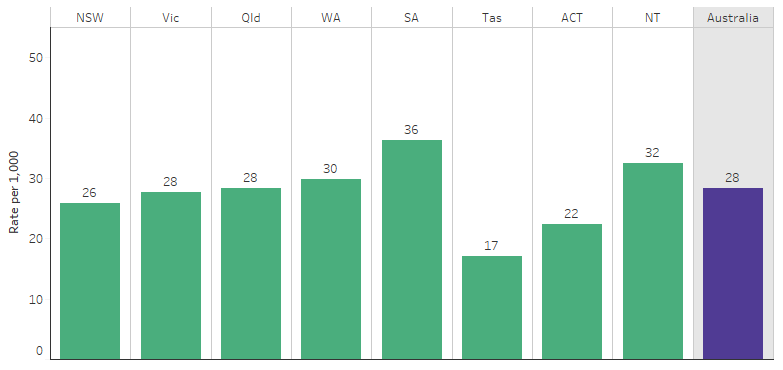

The hospitalisation rate for mental-health related conditions among Indigenous Australians was 28 hospitalisations per 1,000 population, with the highest hospitalisation rate for those aged 35–44 years (58 hospitalisations per 1,000 population) (Table D1.18.14).

From July 2017 to June 2019, the hospitalisation rate for mental health-related conditions for Indigenous Australians was highest in South Australia (36 per 1,000 population), followed by the Northern Territory (32 per 1,000 population). The rate was lowest in Tasmania (17 per 1,000 population) (Table 1.18.15, Figure 3.10.3).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the hospitalisation rate for mental health-related conditions among Indigenous Australians was 1.8 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Figure 3.10.3: Hospitalisation rates for mental health-related conditions for Indigenous Australians, by state and territories, July 2017 to June 2019

Source: Table D1.18.15. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

In some circumstances, patients admitted to hospital are provided with care comparable to that provided by community mental health care services. They are referred to as ambulatory-equivalent and non-ambulatory-equivalent mental health services. Ambulatory-equivalent care comprises a wide range of mental health services that can be classified as being with or without specialised psychiatric care, from care provided in primary care settings through to ambulatory care, community-based mental health care and same day admitted patient mental health care in psychiatric or general hospitals. Non-ambulatory-equivalent mental health care settings include admitted patient mental health care in specialised psychiatric and general hospitals and residential mental health care.

From July 2017 to June 2019, there were 3,258 hospitalisations (a crude rate of 2.0 per 1,000 population) for ambulatory-equivalent care that involved specialised psychiatric care for Indigenous Australians (Table D3.10.7). After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to receive ambulatory-equivalent care that involved specialised psychiatric care (age-standardised rate of 2.4 compared with 5.7 per 1,000 population respectively).

For non-ambulatory-equivalent care, there were 20,857 hospitalisations (a crude rate of 3.5 per 1,000 population) that involved specialised psychiatric care for Indigenous Australians.

Of the 20,857 non-ambulatory-equivalent episodes of care that involved specialised psychiatric care the majority (87% or 18,123 hospitalisations) occurred in non-remote areas. Two-thirds (69% or 11,731 hospitalisations) of non-ambulatory-equivalent episodes of care that did not include specialised psychiatric care occurred in non-remote areas (Table D3.10.7).

In 2017–18, the rate of available psychiatric beds (in public psychiatric hospitals and specialised mental health units in public hospitals) decreased as remoteness increased, ranging from 31 per 100,000 in Major cities to 9.1 per 100,000 in Remote and Very remote areas combined. (Table D3.10.10).

From July 2017 to June 2019, for all non-ambulatory equivalent mental health care, the average length of stay was 16 days for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous patients (Table D3.10.8).

In 2020–21, 5.7% (37,587 presentations or 478 per 10,000 population) of all emergency department presentations for Indigenous patients were mental health-related, compared with 3.3% for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022b).

Homelessness service clients

In 2020–21, 31% (18,187) of Indigenous clients seeking specialist homelessness service assistance presented with a current mental health issue. This was an increase of 997 clients (or 5.8%) since 2019–20 (AIHW 2021a).

Change over time

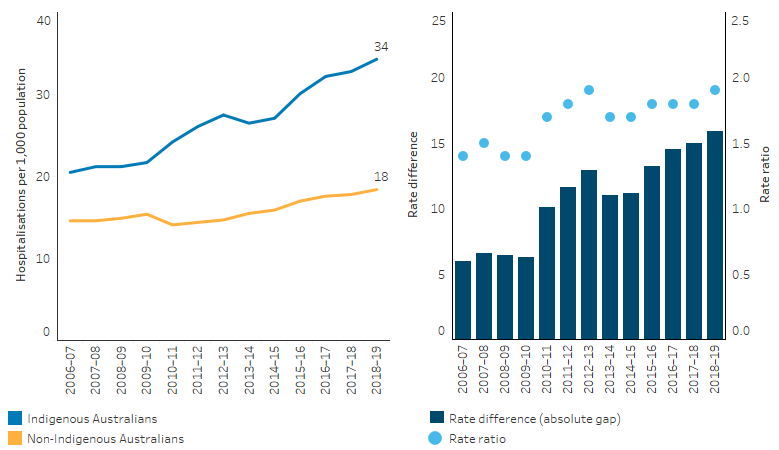

Between 2006–07 and 2018–19, rate of hospitalisation for mental health-related conditions (based on principal diagnosis) among Indigenous Australians increased by 69% in the six jurisdictions with Indigenous identification data of adequate quality (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory).

In the decade between 2009–10 and 2018–19, there was a 52% increase in the hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians due to mental health-related conditions (from 19 to 29 per 1,000 hospitalisations, crude rates). Trends for Indigenous Australians differed by sex: there was a 58% increase for females in this period, compared with a 46% increase for males (Table D1.18.20).

Based on age-standardised rates, increases in the hospitalisation rate between 2009–10 and 2018–19 for Indigenous Australians was higher than for non-Indigenous Australians (increasing by 52% compared with 30%). This resulted in a widening of the absolute gap (rate difference) over the period (Table D1.18.20, Figure 3.10.4).

Figure 3.10.4: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for mental health-related conditions, by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D1.18.15. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Research and evaluation findings

Colonisation disrupted sources of social and emotional wellbeing within cultures, communities and families, with resulting intergenerational impacts (Calma et al. 2017). These effects are exacerbated by the negative impact of social determinants today, including the forced removal of children from families, racism and broader forms of social exclusion. A demographic assessment of life outcomes facing Stolen Generations survivors used data from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey to identify individuals who were born before 1972 and who reported being removed from their families. In 2018–19, compared with other older Indigenous Australians who did not report having been removed, the Stolen Generations aged 50 years and over were 1.4 times as likely to have poor mental health (AIHW 2021b).

An analysis of over 400 Indigenous suicide deaths in Queensland from 1994 to 2007 found that only 23% had received treatment from a mental health professional in their lifetime, compared with 42% of non-Indigenous cases (De Leo et al. 2011). Only 10% of Indigenous cases were seen by a mental health professional in the 3 months prior to suicide, compared with 26% of non-Indigenous cases.

Early intervention can prevent suicide deaths. However, stigma associated mental disorders is a key factor preventing people from accessing the care they need (Knaak et al. 2017). Research into the effects of stigma and discrimination related to problematic alcohol and other drug use in Queensland found that most participants felt they could not obtain support for mental health and problematic alcohol and other drug use when they needed it (QMHC 2020). Participants felt judged by mainstream service providers, and noted the services lacked an understanding of the experiences of Indigenous Australians. They hesitated to seek support from service providers because of ‘personal shame and fear that they will be judged by staff or recognised by other Indigenous patients’ and tended to access mainstream services only in a crisis. Participants suggested that mainstream services could help overcome this barrier of shame associated with mental health issues, for example by enabling discreet access to the building.

Other barriers to accessing mental health services include perceived potential for unwarranted intervention from government organisations, long wait times (more than one year), lack of inter-sectoral collaboration and the need for culturally competent and culturally safe approaches, and effective diagnosis (McGough et al. 2017; Williamson et al. 2010).

Mental health assessment for Indigenous Australians

Research into the extent to which primary health care services undertake social and emotional wellbeing (SEWB) screening analysed 3,407 Indigenous client records between 2012 and 2014 from a sample of 100 government and community controlled Indigenous primary health care (PHC) services in the Northern Territory, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia (Langham et al. 2017). Screening involved the use of standard SEWB tools, such as the Kessler 5, Kessler 6, Kessler 10, Patient Health Questionnaire 2, Patient Health Questionnaire 9, and Edinburgh Postnatal Depression screen. Other standard tools could also be used. There was wide variation in the screening rate at the state/territory level, and variation was also related to PHC service characteristics. Overall, around one-quarter (26.6%) of clients were screened for SEWB in the 2 years prior to the audit, and no further action was taken for 25.4% of clients for whom a SEWB concern was identified. Langham and others (2017) suggested the lack of national guidelines for SEWB screening and management means there is no guidance for best practice when providing these services, which may contribute to the wide variation in SEWB service provision. However, the data set used for this study was not a representative sample of Indigenous PHC services, and only captured those that were part of the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease research project, a national research-based Continuous Quality Improvement initiative focused on improving Indigenous primary health care.

The nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) is a depression subscale of the Patient Health Questionnaire, which has been used for nearly two decades in primary health care facilities as a screening tool for depression and for assessing symptom severity in adults (Costantini et al. 2021). It has also been used in a wide range of cultural settings, but had not been formally validated for use in Indigenous Australian communities (Getting it Right Collaborative Group et al. 2019). The PHQ-9 text was re-worded in “Aboriginal English” and found to be internally consistent in a study with Indigenous Australians from central Australia. The Getting it Right study assessed the validity of the culturally adapted nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (aPHQ-9) as a screening tool for depression among Indigenous Australians attending PHC services. This was a prospective, observational diagnostic accuracy study with 500 participants, undertaken in 10 Indigenous PHC services in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australian, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. The study found that the aPHQ-9 was an effective screening tool for depression in Indigenous Australians, and was regarded as acceptable by 86% of participants, while 13% felt that some or all questions were too personal. While adapting the aPHQ-9 for use with people from five Indigenous language groups, seven key features of depression in Indigenous Australian men not covered by the aPHQ-9 were identified. These were: anger, weakened spirit, homesickness, irritability, excessive worry, rumination, and drug or alcohol use. Additional questions were developed for assessing these features.

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Evaluation Project (the Evaluation Project) identified success factors for suicide prevention and developed a suite of community tools (Dudgeon et al. 2016b). This evaluation recommended that all mental health service provider staff working with Indigenous Australians at risk of suicide, and in Indigenous communities be required to achieve key performance indicators in cultural competence and the delivery of trauma informed care.

Building on the foundation of the Evaluation Project, the Centre of Best Practice in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention (CBPATSISP) was established in 2017 to develop and share evidence about effective suicide prevention approaches for Indigenous people and communities. The work of the CBPATSISP is centred on the rights of Indigenous people and communities to self-determination, and the critical importance of cultural responses to distress alongside clinical approaches. It provides resources and tools to make a real difference in promoting positive mental health and social emotional wellbeing, and in preventing suicide in communities.

Guidelines have been developed containing specific recommendations for the effective and appropriate psychosocial assessment of Indigenous Australians presenting to hospital with self-harm and suicidal thoughts (Leckning et al. 2019). The guidelines are intended to enhance existing practices with aims including developing the cultural competency of hospital staff in providing more culturally responsive and culturally safe mental health services, improving patient satisfaction with hospital services and encouraging help-seeking behaviours.

Accessing mental health services in rural and remote areas

While the prevalence of mental illness is similar across Australia, evidence suggests that people living in Outer regional and Remote areas access mental health services at much lower rates than people living in Major cities and Inner regional areas (DoH 2018). Almost one-fifth (18.6%) of Indigenous Australians live in Remote or Very remote areas (6.7 % in Remote and 11.9% per cent in Very remote), compared with only 2% of non-Indigenous Australians (ABS 2018). There are low numbers of mental health professionals such as psychiatrists, mental health nurses and psychologists in regional and remote areas (DoH 2018). A ‘unique combination of factors’ are believed to contribute to low rates of access to mental health services and high rates of suicide in rural and remote communities. These include poor access to primary and acute health care, social and geographical isolation, limited mental health services, funding restrictions, stigma around mental illness and the cost of travelling to and accessing mental health services (DoH 2018). In addition to these factors, Indigenous Australians also face cultural barriers and a lack of culturally appropriate mental health services. Fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) and outreach services are often provided for communities in these areas. Communities are often not receptive to FIFO workers as they visit for short periods, lack local knowledge and do not build relationships with the community (SCAC Secretariat 2018). Telehealth has increasingly played an important role in mental health service provision in rural and remote Australia, but evidence suggests that access to the internet for telehealth varies widely across these areas (SCAC Secretariat 2018).

Studies have shown that remote culturally appropriate health care may be enhanced by the use of telehealth because it allows care to be provided in the supportive environment of an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health facility. It allows for the advocacy and assistance of an Indigenous health worker and reduces the burden of travel and dislocation from community and family (Caffery et al. 2018). With increasing evidence on the effectiveness of e-mental health interventions for enhancing mental health and wellbeing of remote Indigenous populations, a growing challenge is how to translate promising research findings into service delivery contexts (Bennett-Levy et al. 2017). A review of digital health solutions found there was limited evidence for digital solutions in Indigenous contexts beyond specific examples and pilot projects (Hensel et al. 2019). Digital solutions fell into three categories: remote access to specialists; building and supporting local capability; and patient-directed interventions. Further to telehealth services, some digital Apps treatments have also been found to be effective in treating anxiety and depression in Indigenous Australians, some outcomes being similar to those of non-Indigenous patients. Mental health digital App treatment options if further developed and promoted could help in overcoming barriers to access to mental health care for Indigenous Australians (Titov et al. 2018).

Initiatives to improve cultural competency of mental health services

Two primary mental health care initiatives were introduced through Australia’s national Access to Allied Psychological Services (ATAPS) program—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Mental Health Services (from July 2010) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Services (from July 2011). These initiatives were intended to improve access to, and the cultural appropriateness and cultural safety of, ATAPS services for Indigenous Australians (Reifels et al. 2018). The introduction of these enhanced services increased the uptake of Indigenous ATAPS services between 2010 and 2013 (Reifels et al. 2015). Data from 2015–16 show that, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 4.3 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to use ATAPS (AIHW 2020; DoHA 2012). An evaluation of these services conducted interviews with 31 service providers, but it was limited by a lack of data on the perspectives of Indigenous stakeholders and service users (Reifels et al. 2018). An evaluation of the implementation strategies highlighted the factors that had encouraged the update of ATAPS by Indigenous clients: local service needs assessments; Indigenous stakeholder consultation and partnership development; establishment of clinical governance frameworks; workforce recruitment, clinical/cultural training and supervision; stakeholder and referrer education; and service co-location at Indigenous health organisations. The findings from the evaluation highlighted that national primary mental health care initiatives need to be complemented with local agency-level and provider-level efforts in partnership with Indigenous stakeholders to optimise their integration and use within local Indigenous community and health-care service contexts.

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) have partnered with government service providers to establish new mental health programs, and increased Indigenous Australians’ access to mental health services (Campbell et al. 2018). The Maga Barndi Mental Health Service, run through the Geraldton Regional Aboriginal Medical Service, was introduced to provide a culturally safe service to Indigenous Australians in Geraldton and Midwest Western Australia (Laugharne et al. 2002). Following the commencement of this service, there was a marked increase in use of mental health services by Indigenous Australians in the area, and psychiatric admissions for Indigenous patients at the local hospital were reduced by 58%.

Feedback from practitioners and Indigenous clients

Most mental health and wellbeing services are delivered by non-Indigenous practitioners (Mullins & Khawaja 2017). A qualitative research project conducted semi-structured individual interviews with twelve non-Indigenous psychologists experienced in working with Indigenous Australians and based in Queensland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia, New South Wales and Victoria (in Major cities, Regional and Remote locations). Participants saw flexibility, adaptability and willingness to step beyond traditional psychology as essential. Ongoing attention and effort must be paid to relationships. Trust, respect, honesty, collaboration and safety were fundamental to good relationships with Indigenous clients, their family, community, local Elders, and colleagues. Trauma-informed and client-specific approaches were important and approached cultural competence development as a journey rather than a destination.

Qualitative research conducted with Aboriginal mental health workers working in community mental health services in rural and remote New South Wales found that most of the research participants reported an attitude from other staff that anything ‘Aboriginal’ was their responsibility, and assumed that Indigenous clients would always want to see an Indigenous worker (Cosgrave et al. 2018). One participant reported that they were trying to instil greater cultural understanding among staff, to teach staff that they shouldn’t assume Indigenous clients would want to see an Indigenous worker, and that they should ask the client.

Self-determination in mental health services

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System Interim Report (State of Victoria 2019) recommended expansion of social and emotional wellbeing teams throughout Victoria, and that these teams will be supported by a new Aboriginal Social and Emotional Wellbeing Centre. The Final Report released in 2021, found that culturally safe services were not always available to Aboriginal communities in Victoria. Building on the recommendations of the Interim Report, the Final Report included recommendations to support and resource Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations in delivering culturally safe and appropriate SEWB services, particularly for children and young people (State of Victoria 2021). The Royal Commission also heard significant concerns from Indigenous organisations and experts about the intersections between the mental health and justice systems for Indigenous Australians. Systemic racism and intergenerational trauma contribute to the over-representation of Indigenous Australians in the Victorian justice system. The Commission heard that when Indigenous Australians enter the justice system, mental health supports were often inaccessible or inappropriate.

The Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System Final Report (State of Victoria 2021) built on the interim report to discuss the issues of systemic discrimination that has sustained the inequity in mental health of Indigenous Australians. Among the most disadvantaged Indigenous Australians including the Stolen Generations, children out-of-home care and those who experienced incarceration. The socio-historical and cultural risk factors, combined with intergenerational socioeconomic disadvantage (e.g., poor access to education and housing), social risk factors (e.g., criminal injustice, substance use and violence) and limited access to culturally safe and responsive mainstream services, may have contributed to disengagement from health care among Indigenous Australians. In the interim report, the Commission noted that self-determination in the context of mental health ‘means transferring power and resources to Aboriginal communities to design and deliver their own mental health services while drawing on the skills and expertise of others where needed’. The final report provided several recommendations that would facilitate this change: (a) Indigenous-specific initiatives should ensure better cooperation between governments and respecting Indigenous Australian’s right to self-determination in efforts to improve their health; and (b) the evaluation process of policies and programs involving Indigenous communities should involve Indigenous stakeholders. While these delivery and reforms should be determined by Aboriginal organisations and communities, it also requires support from the Victorian Government. In 2018, the Victorian Government refreshed the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2018–2023 to track government progress to achieve positive outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians. The Commission strongly suggests that the Victorian Government take note of the advice regarding the principles of self-determination.

Implications

Mental health and substance use disorders were the leading cause of the total burden of disease for Indigenous Australians, accounting for almost one-fourth (23%) of the total burden. Mental health and substance use disorders were also the leading contributor to the gap, accounting for one-fifth (20%) of the gap in disease burden between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2021c). While the rate of several types of mental health care and services use may be similar or higher for Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians, there remains unmet need particularly for specialist services, such as clinical psychologists in Remote and Very remote areas.

ACCHS have an important role in delivering culturally safe mental health services to Indigenous communities, as the community-based model of care can be empowering for Indigenous Australians with mental illness (SCAC Secretariat 2018). Aboriginal community controlled substance use treatment and support services also play an important role. Indigenous community-led innovations are developing local, culturally based SEWB programs and new ways of working with mainstream systems (Calma et al. 2017). There is also a need to support growth in the Indigenous mental health workforce and build the cultural competence of the mainstream mental health workforce.

To support access to mental health services for Indigenous Australians, all mental health services need to offer a culturally safe environment. Culturally valid understandings must shape the provision of services and guide assessment, care and management of Indigenous Australians’ health (DoH 2017). There are a range of tools and strategies practitioners can use to help them develop key competencies to be culturally respectful and effective in their practice in Indigenous mental health. Telehealth has great potential to deliver care in culturally appropriate settings such as ACCHS and reduces the burden of travel on patients, allowing them to remain with their family and community.

A lack of understanding regarding Indigenous Australians’ life experiences, stressors, and the concept of SEWB and its relationship with mental health, has ‘posed problems for policy-makers and to mental health service delivery in the past two decades’ (Dudgeon et al. 2016a). The solutions for addressing mental health issues for Indigenous Australians requires a ‘best of both worlds’ approach, including clinical and specialised, culturally informed areas of practice (Calma et al. 2017).

The Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Declaration proposes that change is needed across all levels of the mental health system, and that an approach guided by self-determination is needed (Dudgeon et al. 2016a). In particular, Indigenous leadership is needed to ensure that culturally informed practices are available in addition to clinical responses, and that there is an appropriate balance of clinical and culturally informed mental health system responses to mental health problems among Indigenous Australians (Calma et al. 2017). New approaches are needed that acknowledge disempowerment, cultural losses, racism, and how the cumulative, stressful effect of entrenched poverty and disadvantage adversely affect Indigenous mental health. Key responses needed are the healing of trauma in a culturally appropriate context in a way that includes families and communities as well as individuals, and those that are aimed at strengthening SEWB, which is a protective factor. The Draft Implementation Plan for the Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Declaration was open to public consultation in June 2022 and is currently being finalised.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have heightened the urgency of the need for accessible and affordable internet access and culturally safe and trauma-informed digital and telehealth services for Indigenous communities (Dudgeon et al. 2020).

Reform of the Australian mental health system is a focus of the Australian Government’s Long Term National Health Plan, including the Vision 2030 for Mental Health and Suicide Prevention blueprint and implementation roadmap. Vision 2030 has been delivered through a unified system that takes a whole-of-community, whole-of-life and person-centred approach to mental health; a vision to provide easily navigated, coordinated and balanced community-based services that are offered early to meet each individual's needs and prevent escalating concerns (National Mental Health Commission 2022).

The National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017–2023 provides a dedicated focus on Indigenous Australian social and emotional wellbeing and mental health and sets out a comprehensive and culturally appropriate stepped care model that applies to both Indigenous specific and mainstream health services (Commonwealth of Australia 2017). The framework is designed to complement the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan (the Fifth Plan), endorsed in 2017. The Fifth Plan seeks to establish a national approach for collaborative government effort from 2017–2022 across eight targeted priority areas, including improving Indigenous Australian mental health and suicide prevention.

The National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Agreement (the Mental Health Agreement) sets out the shared intention of the Commonwealth, state and territory governments to work in partnership to improve the mental health of all Australians and ensure the sustainability and enhance the services of the Australian mental health and suicide prevention system. The Mental Health Agreement aims to achieve systemic, whole-of-government reform to deliver a comprehensive, coordinated, consumer-focused mental health and suicide prevention system with joint accountability across all governments. The Mental Health Agreement commits to continuing work under the Fifth Plan and responds to the recommendations of the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Mental Health, the National Suicide Prevention Adviser’s Final Advice, and the House of Representatives Select Committee on Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Final Report. The priority areas addressed within the Mental Health Agreement include regional planning and commissioning, priority populations, stigma reduction, safety and quality, gaps in the system of care, suicide prevention and response, psychosocial supports outside the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS), national consistency for initial assessment and referral, workforce, and data and evaluation. The Mental Health Agreement identifies Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as a priority population, and commits to work in partnership with Indigenous Australians, their communities, organisations and businesses to improve their access to, and experiences of, social and emotional wellbeing, and mental health and suicide prevention services. The Mental Health Agreement is supported by bilateral schedules with all states and territories. Bilateral schedules outline funding commitments to deliver specific initiatives at a state-level and allow for regional variability in the delivery of those initiatives. The Mental Health Agreement and bilateral schedules are publicly available on the Federal Financial Relations Website.

The Indigenous Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Clearinghouse managed by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare was established to build the evidence base to improve mental health services and outcomes for Indigenous Australians. It includes an exploration of mental health and suicide related topics, research articles, and a research and evaluation register.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The Agreement has recognised the importance of Indigenous Australians enjoying high levels of social and emotional wellbeing by establishing the following outcome and target to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Outcome 14 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people enjoy high levels of social and emotional wellbeing.

- Target – Significant and sustained reduction in suicide of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people towards zero.

The National Agreement has also recognised that strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are fundamental to improved life outcomes for Indigenous Australians and that all activities to be implemented under the Agreement need to support, promote and not diminish these cultures. In particular, the Agreement has established the following outcomes to support the cultural wellbeing of Indigenous Australians:

- Outcome 15 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people maintain a distinctive cultural, spiritual, physical and economic relationship with their land and waters.

- Target – By 2030, a 15 per cent increase in Australia’s landmass subject to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s legal rights or interests.

- Target – By 2030, a 15 per cent increase in areas covered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s legal rights or interests in the sea.

- Outcome 16 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported and flourishing.

- Target – By 2031, there is a sustained increase in number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (the Health Plan), was developed in genuine partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders. Priority 6 of the Health Plan focuses on ‘Social and emotional wellbeing and trauma-aware, healing-informed approaches’ to service delivery, and includes the following objectives:

- Objective 6.1 Update and implement a strategic approach for social and emotional wellbeing

- Objective 6.2 Support Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to deliver social and emotional wellbeing services

- Objective 6.3 Support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations to provide leadership on healing and social and emotional wellbeing

- Objective 6.4 Implement training and other support across the whole health system to better understand and respond to social and emotional wellbeing in all aspects of life.

Priority 10 of the Health Plan focuses on mental health and suicide prevention. A number of objectives focus on strengthening culturally safe suicide prevention services, improving continuity of care, and implementing key reforms to Indigenous mental health and suicide prevention policy.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. ABS Canberra.

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report—key results 2016–17. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services report no. 9. Cat. no. IHW 196. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2019. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report—key results 2017–18. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services web report. Cat. no. IHW 212. . Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2020. Mental health services in Australia web report. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2021a. Specialist homelessness services annual report 2020–21. Vol. 5 (ed., AIHW). Canberra: Australian Government.

-

AIHW 2021b. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Stolen Generations aged 50 and over: updated analyses for 2018–19. Cat. no. IHW 257. Canberra.

-

AIHW 2021c. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 – Key findings. Cat. no. BOD 28. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 19 October.

-

AIHW 2022a. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: results from the nKPI and OSR collections. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed September 2022.

-

AIHW 2022b. Mental health services in Australia. Canberra: AIHW.

-

Australian Psychological Society 2018. Accessibility and quality of mental health services in rural and remote Australia APS response to the Senate Community Affairs References Committee Inquiry - Submission 103.

-

Bennett-Levy J, Singer J, DuBois S & Hyde K 2017. Translating e-mental health into practice: what are the barriers and enablers to e-mental health implementation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health professionals? Journal of medical Internet research 19:e1.

-

Caffery LJ, Bradford NK, Smith AC & Langbecker D 2018. How telehealth facilitates the provision of culturally appropriate healthcare for Indigenous Australians. Journal of telemedicine and telecare 24:676-82.

-

Calma T, Dudgeon P & Bray A 2017. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing and mental health. Australian Psychologist 52:255-60.

-

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

-

Commonwealth of Australia 2017. National Strategic Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ Mental Health and Social and Emotional Wellbeing 2017-2023. Canberra: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

-

Cosgrave C, Maple M & Hussain R 2018. Factors affecting job satisfaction of Aboriginal mental health workers working in community mental health in rural and remote New South Wales. Australian Health Review 41:707-11.

-

Costantini L, Pasquarella C, Odone A, Colucci ME, Costanza A, Serafini G et al. 2021. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders 279:473-83.

-

De Leo D, Sveticic J, Milner A & McKay K 2011. Suicide in Indigenous populations of Queensland. Australian Academic Press.

-

DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) 2017. My Life My Lead - Opportunities for strengthening approaches to the social determinants and cultural determinants of Indigenous health: Report on the national consultations. Canberra

-

DoH 2018. Senate Community Affairs References Committee Inquiry and Report into the Accessibility and Quality of Mental Health Services in Rural and Remote Australia - Submission 30. Canberra: Department of Health.

-

DoHA (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing) 2012. Operational Guidelines for the Access to Allied Psychological Services Initiative. Canberra: Department of Health and Ageing.

-

Dudgeon P, Calma T, Brideson T & Holland C 2016a. The Gayaa Dhuwi (Proud Spirit) Declaration–a call to action for aboriginal and torres strait islander leadership in the Australian mental health system. Advances in Mental Health 14:126-39.

-

Dudgeon P, Derry K & Wright M 2020. A National COVID-19 Pandemic Issues Paper on Mental Health and Wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Perth.

-

Dudgeon P, Milroy J, Calma T, Luxford Y, Ring IT, Walker R et al. 2016b. Solutions That Work: What the evidence and our people tell us. Perth: ATSISPEP.

-

Getting it Right Collaborative Group, Hackett ML, Teixeira‐Pinto A, Farnbach S, Glozier N, Skinner T et al. 2019. Getting it Right: validating a culturally specific screening tool for depression (aPHQ‐9) in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Medical Journal of Australia 211:24-30.

-

Hensel JM, Ellard K, Koltek M, Wilson G & Sareen J 2019. Digital health solutions for indigenous mental well-being. Current psychiatry reports 21:68.

-

Knaak S, Mantler E & Szeto A 2017. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc Manage Forum 30:111-6.

-

Langham E, McCalman J, Matthews V, Bainbridge RG, Nattabi B, Kinchin I et al. 2017. Social and emotional wellbeing screening for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders within primary health care: a series of missed opportunities? Frontiers in public health 5:159.

-

Laugharne J, Glennen M & Austin J 2002. The “Maga Barndi” mental health service for Aboriginal people in Western Australia. Australasian Psychiatry 10:13-7.

-

Leckning B, Ringbauer A, Robinson G, Carey T, Hirvonen T & Armstrong G 2019. Guidelines for best practice psychosocial assessment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people presenting to hospital with self-harm and suicidal thoughts. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

-

McGough S, Wynaden D & Wright M 2017. Experience of providing cultural safety in mental health to Aboriginal patients: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing.

-

Mullins C & Khawaja NG 2017. Non‐Indigenous Psychologists Working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Towards Clinical and Cultural Competence. Australian Psychologist.

-

National Mental Health Commission 2022. Vision 2030. Viewed.

-

QMHC (Queensland Mental Health Commission) 2020. Don't Judge, and Listen: Experiences of stigma and discrimination related to problematic alcohol and other drug use. Brisbane.

-

Reifels L, Bassilios B, Nicholas A, Fletcher J, King K, Ewen S et al. 2015. Improving access to primary mental healthcare for Indigenous Australians. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 49:118-28.

-

Reifels L, Nicholas A, Fletcher J, Bassilios B, King K, Ewen S et al. 2018. Enhanced primary mental healthcare for Indigenous Australians: service implementation strategies and perspectives of providers. Global health research and policy 3:16.

-

SCAC Secretariat 2018. Community Affairs References Committee: Accessibility and quality of mental health services in rural and remote Australia. (ed., Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs). Canberra: SSCCA.

-

SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision) 2020. Report on Government Services 2020. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

-

State of Victoria 2019. Royal Commission into Victoria's Mental Health System Interim Report. Melbourne: Victorian Government Printer.

-

State of Victoria 2021. Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Final Report, Volume 3: Promoting inclusion and addressing inequities, Parl Paper No. 202, Session 2018–21 (document 4 of 6).

-

Titov N, Schofield C, Staples L, Dear BF & Nielssen O 2018. A comparison of Indigenous and non-Indigenous users of MindSpot: an Australian digital mental health service. Australasian Psychiatry:1039856218789784.

-

WHO (World Health Organization) 2020. Social determinants of health. Geneva: WHO. Viewed 8 October 2020.

-

Williamson AB, Raphael B, Redman S, Daniels J, Eades SJ & Mayers N 2010. Emerging themes in Aboriginal child and adolescent mental health: findings from a qualitative study in Sydney, New South Wales. The Medical Journal of Australia 192:603-5.

-

World Health Organization 2022. Mental health: strengthening our response. Viewed December 2022.