Key messages

- If left untreated, sexually transmissible infections (STIs) can have serious long-term health consequences, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, adverse pregnancy outcomes, miscarriage, and neonatal infections. Rates of infection for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are higher than those for non-Indigenous Australians.

- Among First Nations people in 2020–2022, young people aged 15–24 had the highest notification rates for chlamydia and gonorrhoea. The notification rate of both infectious syphilis and hepatitis C were highest among First Nations people aged 25–34. Hepatitis B notification rates were highest for First Nations people aged 45–54.

- In 2019–2021, there were 59 notifications (2.3 per 100,000 population) of HIV for First Nations people. First Nations people aged 25–39 (4.4 per 100,000 population) had the highest HIV notification rate, compared with those aged 40 and above (3.0 per 100,000 population) and those aged 15–24 (2.5 per 100,000 population).

- Of newly diagnosed HIV infections in 2019–2021, 29% of notifications among First Nations people and 59% of notifications among non-Indigenous Australians were classified as late or advanced diagnoses.

- As at December 2018, the vaccination coverage for hepatitis B for children aged 2 years was 97% for First Nations children and 96% for other Australian children.

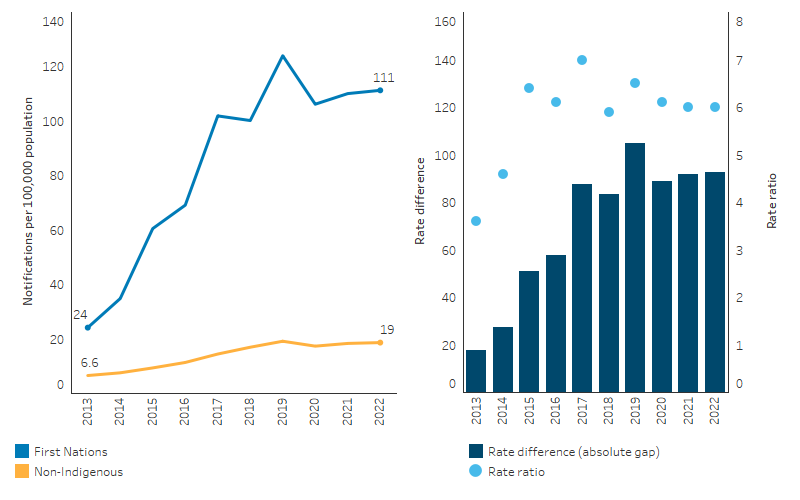

- Infectious syphilis notification rates among First Nations people increased from 22 to 111 per 100,000 population between 2013 and 2022.

- Between 2013 and 2022, notification rates among First Nations people decreased for chlamydia and hepatitis B, increased for infectious syphilis, and there was no statistically significant change for gonorrhoea and hepatitis C. Between 2010–2012 and 2019–2021, HIV notification rates for First Nations people almost halved. Note that changes in notification rates over time are influenced by a range of factors including access to health care, improved screening and improved accuracy of tests.

- Between 2010–2012 and 2019–2021, the percentage of HIV notifications that were late or advanced diagnoses decreased from 46% to 29% for First Nations people.

- An independent evaluation of the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation’s (NACCHO) role under the Enhanced Syphilis Response (ESR) Program (2017–18 to 2020–21), highlighted the leadership role played by NACCHO while working collaboratively across the community-controlled health sector. The resulting trust and relationship between ESR stakeholders also contributed to the seamless transition into managing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on First Nations communities. Systematic efforts to normalise STI testing within services to circumvent shame and stigma were recognised as drivers of increased acceptability and uptake among First Nations young people.

Why is it important?

Sexual health is another important early intervention area that can result in positive gains over the life course, particularly for adolescents and young people. For this to be successful, young people must have the knowledge and tools to manage their sexual, reproductive and mental health. For young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, this means access to culturally safe and responsive sexual and reproductive health services and promotion activities, including age-appropriate sexual development education. To ensure the health of individuals and communities, early detection and treatment of sexually transmissible infections (STIs) are vital to prevent further spread. If outbreaks do occur, it is critical that responses embed point-of-care testing as a way to prevent further transmission, including through routine antenatal care to minimise mother to child transmission (Department of Health 2019; Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

This measure reports on the following STIs: chlamydia; gonorrhoea; non-congenital infectious syphilis (≤2 years duration) (henceforth referred to as ‘infectious syphilis’); and the bloodborne viruses: hepatitis B and C; and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Since the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV infections, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) notifications have decreased substantially, and AIDS surveillance is no longer a reliable measure of the HIV epidemic. Rather, focus moved to monitoring HIV infections at their first diagnosis (see Federal Register of Legislation – National Health Security (National Notifiable Disease List) Amendment Instrument 2016 (No. 1) for more information). Consequently, AIDS was removed from the National Notifiable Disease List in 2016 and this measure no longer captures data on AIDS.

Globally, STIs pose a significant impact on sexual and reproductive health and have remained a major public health challenge that requires serious attention (Otu et al. 2021; Starrs et al. 2018; World Health Organization 2023; Zheng et al. 2022). If left untreated, STIs can have serious long-term health consequences, such as pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, adverse pregnancy outcomes, miscarriage, and neonatal infections. Untreated syphilis can cause heart and brain damage (Bowden et al. 2002; Campbell et al. 2011; Department of Health 2014; Guy et al. 2012). Syphilis can also be passed from mother to child before or during birth (called ‘congenital syphilis’) which can cause miscarriage or stillbirth. It can also cause other serious health problems in babies, including organ, brain or nerve damage (Department of Health Victoria 2024). Chlamydia, gonorrhoea and syphilis are currently curable (World Health Organization 2023) but cases are often asymptomatic for long periods (Bowden et al. 2002). There is also evidence that STIs like gonorrhoea and syphilis can enhance transmission of HIV (Cohen 1998; World Health Organization 2023). First Nations people currently experience a relatively high number of notifications for bacterial STIs, relative to their representation in the total population. Although rates of HIV are not particularly high, First Nations people are possibly more susceptible due to the high rates of STIs (Australasian Sexual Health Alliance 2017).

HIV is a bloodborne virus that targets the immune system and gradually weakens the body’s immune response. As the body becomes immunodeficient, it is at increased susceptibility to a wide range of infections and some types of cancers. The advanced stage of HIV infection is AIDS, which can take years to develop and is characterised by development of severe illnesses and infections and certain cancers such as lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. However, with appropriate treatment, HIV is now a manageable chronic health condition with patients able to lead long and healthy lives (World Health Organization 2020). The global success in managing HIV as a chronic condition through access to prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and care highlights a pathway towards long, healthy lives for those affected, provided they have access to the necessary health services. For First Nations people, achieving similar outcomes necessitates overcoming unique barriers, including access to culturally appropriate healthcare. A report by the Kirby Institute emphasises that the integration of cultural safety into healthcare delivery is crucial. Addressing these specific challenges can ensure that global advancements in HIV management effectively extend to First Nations people, enhancing health outcomes by making treatment more accessible and culturally sensitive (King et al. 2022b).

Hepatitis B and C are bloodborne viruses that cause inflammation of the liver. It is estimated that of the 1% of the Australian population that is living with chronic hepatitis B, 9% are First Nations people (MacLachlan et al. 2013). As these forms of hepatitis can become chronic, they can cause serious illness and can also progress to cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, and premature death (Australasian Sexual Health Alliance 2017). Hepatitis B is transmitted through exposure to infective blood such as through shared injecting needles and sexual contact, but this disease is vaccine preventable. Hepatitis C is most commonly transmitted through shared injecting needles and there is no vaccine available (World Health Organization 2019). While no vaccine is available, effective treatment options are available, and can cure more than 95% of people (HealthDirect 2022).

Notification data includes cases that have been tested, diagnosed, and notified to health authorities, representing only a proportion of the total incidence of disease. As the data relates to notifications rather than people, it also does not allow analysis of the person-level experience. Changes in notification rates over time are influenced by a range of factors including access to health care, improved screening programs for First Nations people and improved accuracy of tests. The completeness of Indigenous status in the data is also an issue and varies by jurisdiction. Improved primary health care can lead to increased testing and a corresponding increase in notification rates.

In July 2020, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people and communities.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations people’s health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

Burden of disease

Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) is a measure of the years of healthy life lost from death and illness at the population level. One DALY is equivalent to the loss of one year of healthy life, through either premature death or from living with an illness or injury (AIHW 2022b).

In 2018, among First Nations people, in relation to bloodborne viruses:

- HIV/AIDS was responsible for 122 years of healthy life lost, equivalent to 0.2 DALY per 1,000 population. Unsafe sex was estimated to contribute to 76% of the burden due to HIV/AIDS, and unsafe injecting practices was estimated to contribute 17%.

- Hepatitis B (acute) was responsible for 49 years of healthy life lost, equivalent to 0.1 DALY per 1,000 population. One-third (33%) of the burden due to hepatitis B was attributable to unsafe injecting practices, and 19% to unsafe sex.

- Hepatitis C (acute) was responsible for 0.8 years of healthy life lost. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of this burden was attributable to unsafe injecting practices, and about 5% to unsafe sex (AIHW 2022a).

Disease burden estimates for STIs among First Nations people in 2018 show that:

- Chlamydia was responsible for 53 years of healthy life lost, equivalent to 0.1 years per 1,000 population. All of the burden due to chlamydia was due to the impact of living with ill health (rather than premature death)

- Gonorrhoea was responsible for 17 years of healthy life lost – 99.8% of this was due to the impact of living with ill health (0.2% was due to premature death)

- Syphilis was responsible for 2.9 years of healthy life lost, 99.7% of the burden due to the impact of living with poor health (0.3% due to premature death) (AIHW 2022a). Note that these data relate to 2018, and may not reflect current burden, with an ongoing outbreak of infectious syphilis among First Nations people living in remote and rural areas of Australia.

Data findings

HIV, chlamydia, infectious syphilis, gonorrhoea, hepatitis B and C are notifiable diseases in each state and territory in Australia. These data are reported from states and territories to the Australian Government under the provisions of the National Health Security Act 2007. Notifications data used in this measure are sourced from 2 national level data repositories:

- HIV notifications are sourced from the National HIV Registry, which is maintained by the Kirby Institute, a research institute based at the University of NSW (King et al. 2022b).

- Chlamydia, infectious syphilis, gonorrhoea, hepatitis C and hepatitis B notifications are drawn from the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), which is maintained by the Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

The NNDSS and the National HIV registry aim to monitor, control and prevent the occurrence and spread of infectious diseases listed on the National Notifiable Disease List.

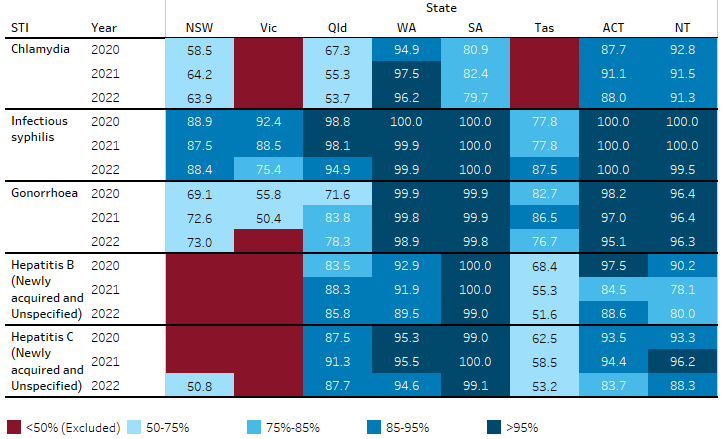

The completeness of Indigenous status information varies by disease and by state and territory. In this measure, and consistent with general NNDSS reporting conventions, the analysis has been limited to jurisdictions where Indigenous status completeness was greater than 50% for the specified disease for all years in the specified time period.

Data for HIV are reported nationally for the years presented, with very high completeness rates (for example, 100% in 2021). For the other notifiable conditions, completeness was more variable (Figure 1.12.1, Table D1.12.supp).

Over the 3-year period from 2020 to 2022, jurisdictions included in the analysis were as follows:

- chlamydia: all jurisdictions except Tasmania and Victoria

- infectious syphilis: all jurisdictions

- gonorrhoea: all jurisdictions except Victoria

- hepatitis B: all jurisdictions except New South Wales and Victoria

- hepatitis C: all jurisdictions except New South Wales and Victoria.

When considering time trends over the decade from 2013 to 2013, jurisdictions included in the analysis were:

- chlamydia: Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory

- infectious syphilis: all jurisdictions

- gonorrhoea: all jurisdictions except Victoria

- hepatitis B: all jurisdictions except New South Wales and Victoria

- hepatitis C: all jurisdictions except New South Wales and Victoria.

Similarly, when reporting data by remoteness area, analysis has been limited to where Indigenous status completeness was greater than 50% across all years for the specified disease and in all 5 remoteness areas (Major cities, Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote, and Very remote areas) where Indigenous status completeness was greater than 50% across all years for the specified disease and remoteness areas (see Table D1.12.supp). For the data period reported 2020–2022, completeness was less than 50% for chlamydia in some remoteness areas, and as such analysis by remoteness is not presented for chlamydia.

Caution should be used while interpreting the data, with reference to the completion rates, noting that 50% is a low threshold for completion for inclusion in reporting (see Table D1.12.supp). Throughout this measure, notifications with a ‘not stated’ Indigenous status are excluded.

Various activities are being undertaken to improve the completeness of Indigenous status, such as consideration of the addition of Indigenous status to pathology forms, enhanced data review processes, and continuing education of health care providers (King et al. 2022b).

Figure 1.12.1: Indigenous status completion rates for selected notifiable diseases, by state and territory, 2020 to 2022

Note: See also Table D1.12.supp in Data tables and resources for completion rates for the years 2013 to 2022.

Source: National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data.

Pattern of selected notifiable diseases by age and remoteness

Collectively, the data show that in 2020–2022:

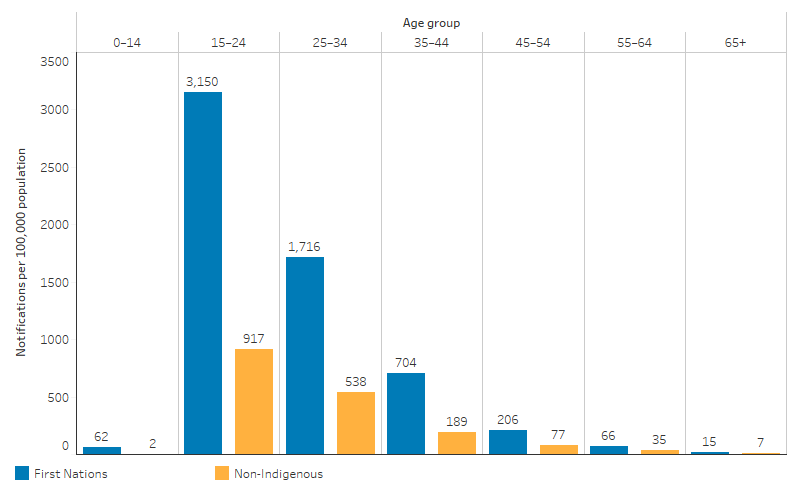

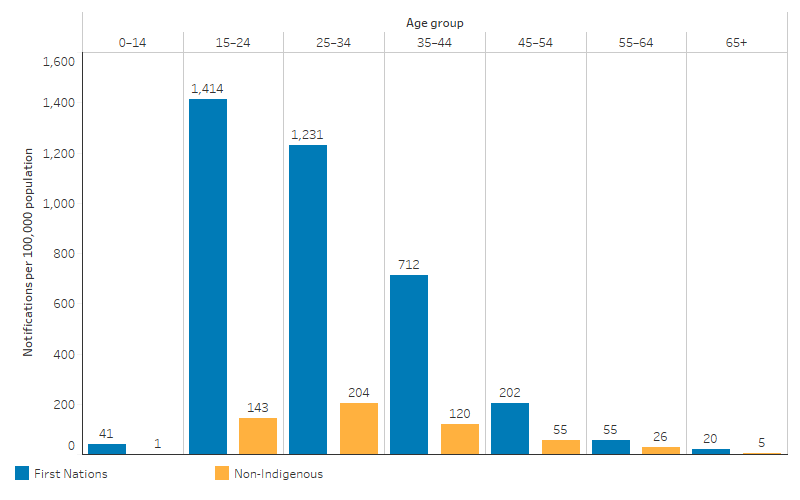

- Among First Nations people, those aged 15–24 had the highest notification rates for chlamydia (3,150 notifications per 100,000 population), and gonorrhoea notifications (1,414 notifications per 100,000 population).

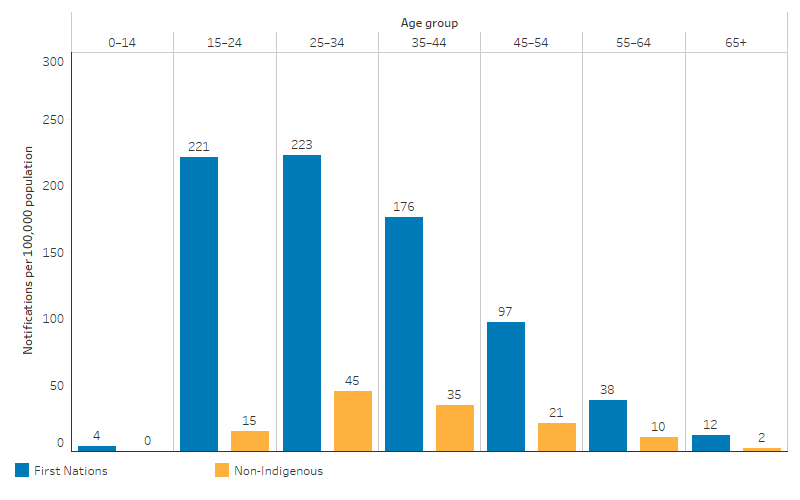

- Infectious syphilis notification rates were highest among First Nations people aged 25–34 (223 per 100,000 population), followed closely by those aged 15–24 (221 per 100,000 population) and 35–44 (176 per 100,000 population).

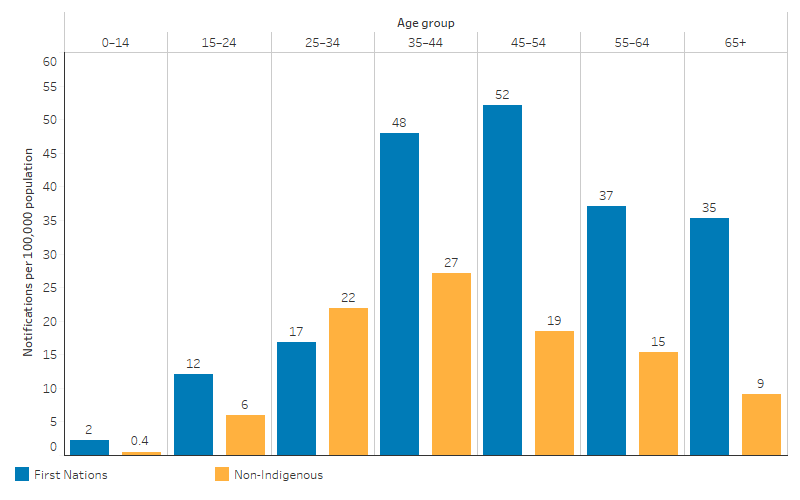

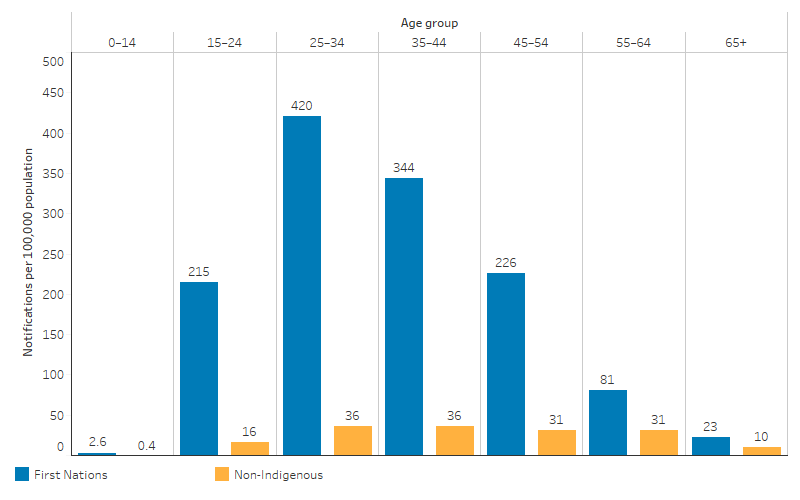

- Hepatitis B notification rates were highest for First Nations people aged 45–54 (52 per 100,000 population) followed closely by those aged 35–44 (48 per 100,000 population). Hepatitis C notification rates were highest for those aged 25–34 (420 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.2).

- Among First Nations people, notification rates of chlamydia, infectious syphilis, gonorrhoea and hepatitis B were higher in remote areas than non-remote areas. In contrast, the rate of hepatitis C notifications was lower in remote than non-remote areas (Table D1.12.18).

- The age-standardised notification rates of gonorrhoea, hepatitis C and infectious syphilis for First Nations people were 6.7, 8.6 and 6.0 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians respectively. For First Nations people, the age-standardised notification rate of chlamydia was 3.4 times and of hepatitis B was 2.0 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.2). In contrast, the age-standardised notification rate for HIV was lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians (rate ratio 0.9) (Table D1.12.8).

More detailed information, organised by type of infection, is presented in subsequent sections.

Chlamydia

Over the 3-year period 2020–2022, there were 23,138 chlamydia notifications (985 per 100,000 population) among First Nations people in the 6 jurisdictions included in the analysis (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory).

In 2020–2022, chlamydia notifications for First Nations people were:

- higher for females than males (1,271 per 100,000 First Nations females compared with 699 per 100,000 First Nations males) (Table D1.12.1)

- higher among those aged 15–24 (3,150 per 100,000 population) than those in other age groups (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.2).

Notification rates were higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians in all age groups (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.2). Among people of all ages, the rate was 4.3 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians (985 compared with 228 per 100,000 population, based on crude rates). Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the notification rate for First Nations people was 3.4 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.2).

Figure 1.12.2: Age-specific notification rates for chlamydia, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA, ACT and the NT combined, 2020–2022

Source: Table D1.12.2. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

Infectious syphilis

Without treatment, someone with syphilis is usually sexually infectious for up to 2 years (Department of Health Victoria 2024). Syphilis has been nationally notifiable since 1991. However, prior to 2004, syphilis cases were reported under the overarching category of syphilis (all), which was inclusive of all cases of syphilis regardless of the stage of infection. Since 2004, the syphilis (all) category was redefined with cases of syphilis reported under 3 new categories: infectious syphilis (<2 years duration), unspecified syphilis (unspecified or >2 years duration) and congenital syphilis (Department of health and Aged Care 2023a). This section focuses on infectious syphilis, with information on congenital syphilis provided in the next section.

In the 3-year period 2020 to 2022, there were 2,881 notifications of infectious syphilis (non-congenital infections of ≤2 years duration) among First Nations people. This corresponds to a rate of 109 notifications per 100,0000 First Nations people, with a similar rate for First Nations males and females (108 and 110 per 100,000) (Table D1.12.1).

Across states and territories, the infectious syphilis notification rates for First Nations people ranged from 35 (in New South Wales) to 310 per 100,000 population (in Western Australia) (excluding Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory due to small numbers) (Table D1.12.1).

Across remoteness areas, rates were lowest for those in Inner and outer regional areas (53 per 100,000 population), followed by those in Major cities (74 per 100,000) and was highest for those in Remote and very remote areas (316 per 100,000) (Table D1.12.18).

Across age groups, the highest rates were observed in the 25–34 age group for both First Nations people (223 per 100,000 population) and non-Indigenous Australians (45 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.3).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structure of the population, the notification rate of infectious syphilis for First Nations people was 6 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (109 compared with 18 per 100,000 population).

Figure 1.12.3: Age-specific notification rates for infectious syphilis, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2020–2022

Source: Table D1.12.2. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

Congenital syphilis

Syphilis can be passed from mother to child before or during birth, which is referred to as congenital syphilis (Sankaran et al. 2023). In the 3-year period 2020 to 2022, there were 25 congenital syphilis notifications among First Nations infants, accounting for over one half of all notifications (45 notifications) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023c; King et al. 2022b).

First Nations infants were disproportionately represented in the notification data, with rates nearly 15 times the rate in non-Indigenous infants (35.8 and 2.4 per 100,000 live births, respectively) (AIHW analysis of data from Department of Health and Aged Care 2023c; King et al. 2022b and ABS 2024).

Gonorrhoea

For the 3-year period 2020–2022, there were 13,967 notifications (572 per 100,000 population) for gonorrhoea among First Nations people in the 7 jurisdictions included in the analysis (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory) – accounting for 26% of all notifications of gonorrhoea (54,492) in Australia (Table D1.12.1).

Gonorrhoea notification rates were higher among First Nations people living in Remote and very remote areas (1,676 per 100,000 population) than among those living in the Major cities (310 per 100,000 population) and Inner and outer regional areas (268 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.18).

The age-specific notification rate for gonorrhoea was highest among First Nations people aged 15–24 (1,414 per 100,000 population), followed by those aged 25–34 (1,231 per 100,000 population). For non-Indigenous Australians, the notification rate was highest for those aged 25–34 (204 per 100,000 population), followed by those aged 15–24 (143 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.4).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the notification rate of gonorrhoea for First Nations people was 6.7 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.2).

Figure 1.12.4: Age-specific notification rates for gonorrhoea, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and the NT combined, 2020–2022

Source: Table D1.12.2. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

Hepatitis B

For the period 2020–2022, there were 322 notifications (21 per 100,000 population) of hepatitis B among First Nations people in the 6 jurisdictions included in the analysis (Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory) (Table D1.12.1).

Hepatitis B notification rates were higher among First Nations people living in Remote and very remote areas (35 per 100,000 population) than among those living in Inner and outer regional areas (13 per 100,000 population) and Major cities (12 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.18).

The age-specific hepatitis B notification rate for First Nations people was highest for those aged 45–54 (52 per 100,000 population), whereas the rate for non-Indigenous Australians was highest for those aged 35–44 (27 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.5).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structure of the population, the rate of hepatitis B notifications for First Nations people was 2.0 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.2).

Figure 1.12.5: Age-specific notification rates per 100,000 for hepatitis B, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2020–2022

Source: Table D1.12.2. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

As at 31 December 2022, among First Nations children aged 1, the vaccination coverage for hepatitis B varied by jurisdiction and was lowest for those living in Western Australia (88%) and highest for those in Tasmania (97%). Among First Nations children aged 2, the coverage rate varied little across jurisdictions, ranging from 95% of those in Western Australia to 99% of those in the Australian Capital Territory and Tasmania (Tables D3.02.2, D3.02.3).

Nationally, 92% of First Nations children aged 1 were vaccinated against hepatitis B, which is slightly lower than other Australian children aged 1 (95%). For those aged 2, 97% of First Nations children had received the vaccination, slightly higher than other Australian children of the same age (96%) (Table D3.02.1).

Hepatitis C

In the 3-year period 2020–2022, there were 2,735 notifications (175 per 100,000 population) for hepatitis C for First Nations people in the 6 jurisdictions included in the analysis (Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory) (Table D1.12.1).

Hepatitis C notification rates were higher among First Nations people living in Major cities (156 per 100,000 population) and in Inner and outer regional areas (154 per 100,000 population), than among those living in Remote and very remote areas (54 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.18).

The age-specific notification rate among First Nations people was highest for those aged 25–34 (420 per 100,000 population). The rate was higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians in every age group, with the largest gap (rate difference) for those aged 25–34 (Table D1.12.2, Figure 1.12.6).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structure of the population, the hepatitis C notification rate for First Nations people was 8.6 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.2).

Figure 1.12.6: Age-specific notification rates per 100,000 for hepatitis C, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and the NT, 2020–2022

Source: Table D1.12.2. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

HIV

In the 3-year period 2019–2021, First Nations people accounted for 2.8% of all HIV notifications (59 of 2,082 notifications), which is equivalent to 2.3 notifications per 100,000 population (Table D1.12.8, Table D1.12.11).

First Nations people aged 25–39 (4.4 per 100,000 population) had a higher HIV notification rate than those aged 15–24 (2.5 per 100,000 population) or 40 and over (3.0 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.9).

The notification rate for HIV was highest for First Nations people in New South Wales (1.5 per 100,000 population), followed by Victoria (4.2 per 100,000 population), Queensland (3.0 per 100,000 population) and Western Australia (2.8 per 100,000 population) (Table D1.12.8).

In the 3-year period 2019–2021, male-to-male sex was the most common HIV exposure category for First Nations people (exposure category for 50.8% of total HIV notifications), followed by exposure to both male-to-male sex and injecting drug use (20.3% HIV notifications), and exposure through heterosexual sex (15.3% HIV notifications). Among non-Indigenous Australians, male-to-male sex was the exposure category for 59.6% of the total HIV notifications, followed by heterosexual sex (25.1% HIV notifications), and exposure to both male-to-male sex and injecting drug use (7.7% HIV notifications) (Table D1.12.10).

In 2019–2021, 29% of notifications in First Nations people and 59% of notifications in non-Indigenous Australians were classified as late or advanced diagnoses. Between 2016–2018 and 2019–2021, the percentages of late or advanced HIV diagnoses decreased for First Nations people (from 36% to 29%) but increased for non-Indigenous Australians (from 48% to 59%) (Table D1.12.12).

Changes over time

Note that changes over time in notifications may be influenced by a range of factors, such as changes in access to screening and in the quality of Indigenous status identification. An increase (or decrease) in notifications may or may not reflect trends in actual incidence of the conditions. States and territories were included in the analysis if information on Indigenous status was available for at least 50% of notifications in all years included in the time trend. In analysing change over time, linear regression has been used. This takes into account all data points in the time period (rather than just the start and end points).

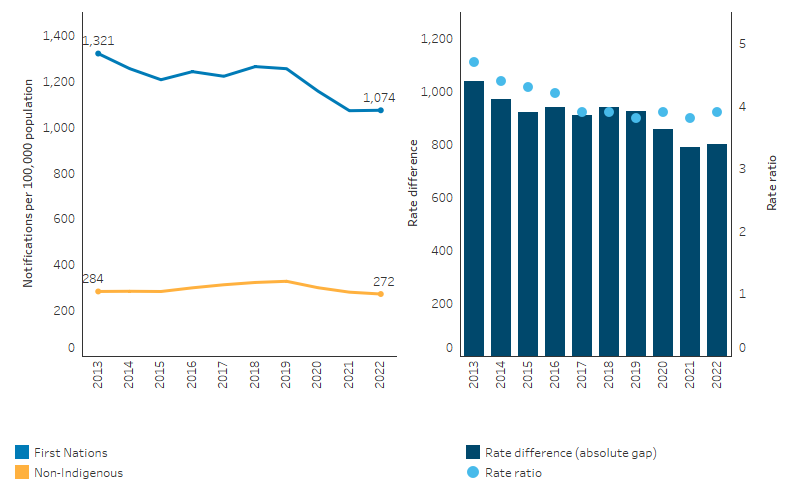

Between 2013 and 2022, notification rates decreased for chlamydia and hepatitis B, and increased for infectious syphilis, while there was no statistically significant change in the notification rates of gonorrhoea and hepatitis C among First Nations people. Between 2010–2012 and 2019–2021, HIV notification rates for First Nations people almost halved.

Note that trends in notifications may be influenced by COVID-19 – for example, through changes to sexual behaviour, restrictions to travel and access to testing (King et al. 2022b).

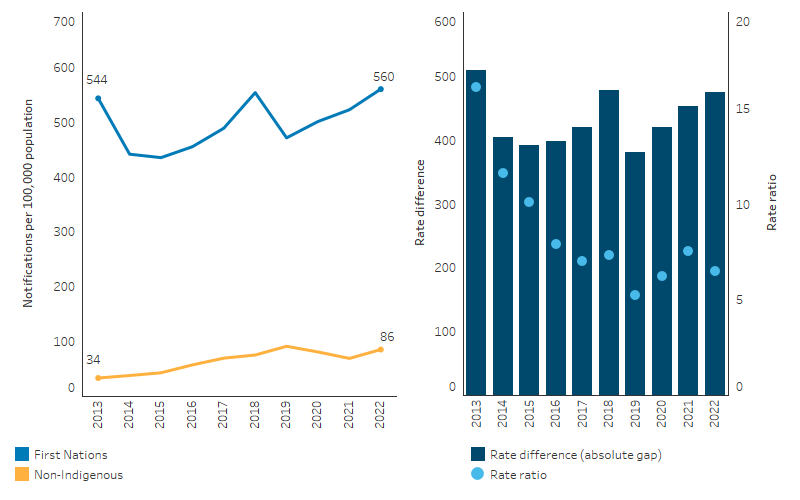

Chlamydia

Between 2013 and 2022, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory combined, the rate of chlamydia notifications among First Nations people decreased from 1,610 to 1,269 per 100,000 population (crude rates). Based on linear regression of data points over the period, the rate of chlamydia notifications among First Nations people declined by an annual average of 33 notifications per 100,000 population (Table D1.12.3).

A larger decline in the rate of chlamydia among First Nations people was evident between 2019 2021 than over the earlier period. This decline coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have influenced notifications. The rate in 2022 was similar to that in 2021 (1,269 and 1,276 notifications per 100,000 population, respectively).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structures between the two populations and over time, the notification rate for First Nations people for chlamydia decreased (by an average of 22 notifications per 100,000 population annually) between 2013 and 2022, with no significant change in the chlamydia rate for non-Indigenous Australians. As a result, the gap in notification rates for chlamydia between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians narrowed between 2013 and 2022 (by an average of 23 notifications per 100,000 population annually) (Table D1.12.3, Figure 1.12.7).

Figure 1.12.7: Age-standardised notification rates for chlamydia, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2013 to 2022

Source: Table D1.12.3. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

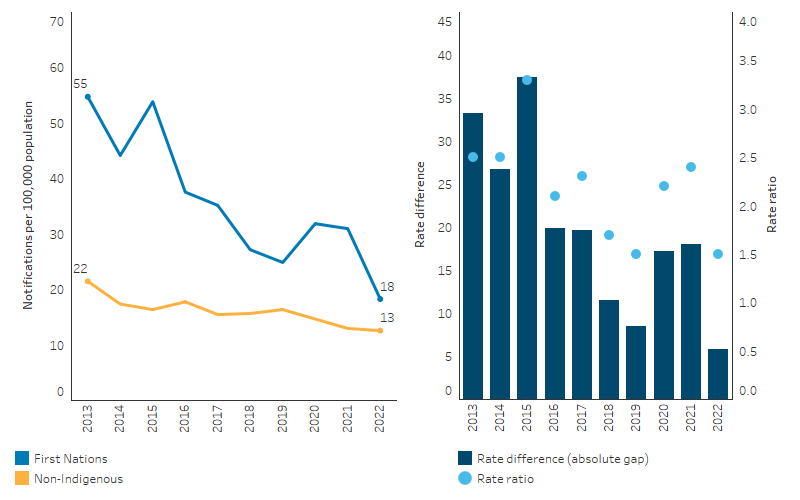

Infectious syphilis

Nationally, between 2013 and 2022, the rate of infectious syphilis among First Nations people generally increased – from 22 to 111 notifications per 100,000 population (crude rates) (Table D1.12.4).

While there was an overall increase in the rate over the decade, the rate of infectious syphilis among First Nations people declined between 2019 and 2020 (from 123 to 106 per 100,000 population), which coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic. The rates of infectious syphilis in 2021 and 2022 among First Nations people (112 and 111 per 100,000 population, respectively) were slightly higher than in 2020 (106 per 100,000 population).

Based on linear regression of crude rates over the period, the rate of infectious syphilis notifications among First Nations people increased by an average of 10.6 notifications per 100,000 annually. Age-standardised data show a similar trend, with an annual increase of 10.3 notifications per 100,000 annually for First Nations people, compared with an increase of 1.5 for non-Indigenous Australians. Reflecting the larger increase for First Nations people, the absolute gap in notification rates for infectious syphilis between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians widened between 2013 and 2022, by an average of 8.8 notifications per 100,000 population annually (Figure 1.12.8, Table D1.12.4).

Figure 1.12.8: Age-standardised notification rates for infectious syphilis, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2013 to 2022

Source: Table D1.12.4. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

In response to an ongoing outbreak of infectious syphilis among First Nations people living in remote and rural areas of Australia, the Multijurisdictional Syphilis Outbreak (MJSO) Working Group was formed by the Communicable Diseases Network of Australia (CDNA) in April 2015. An outbreak of syphilis began in January 2011 in Queensland, extending to the Northern Territory in July 2013, the Kimberley in Western Australia in June 2014, and most recently in South Australia in November 2016.

From the start of the syphilis outbreak on 1 January 2011 through to 30 June 2023, a total of 5,511 infectious syphilis outbreak cases were reported from 4 jurisdictions: 2,020 from Queensland; 2,021 from the Northern Territory; 1,262 from Western Australia; and 208 from South Australia (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b). These outbreak cases consist of:

- First Nations people diagnosed with syphilis who were residing in an outbreak declared region at the time of diagnosis (5,392 cases) (category 1 outbreak cases)

- Sexual contacts of a confirmed outbreak case – which includes First Nations people who do not reside in an outbreak area at the time of diagnosis (36 cases) and non-Indigenous Australians regardless of where they reside (83 cases) (category 2 outbreak cases).

In August 2018, the test and treat model to curb the syphilis outbreak in First Nations communities began at 3 Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS). This was expanded in subsequent phases, and from July 2021, NACCHO has been commissioned to deliver the test and treat model within the prescribed syphilis outbreak regions.

The test and treat model has been rolled out to ACCHS in the following regions: Adelaide, Alice Springs, Bamaga, Barkley Region, Broome, Cairns, Ceduna, Coober Pedy, Darwin, East Arnhem, Innisfail, Kalgoorlie, Katherine, Kimberley, Kintore, Mareeba, Mt Isa, Palm Island, Pilbara, Port Augusta, Port Lincoln, Rockhampton, Tennant Creek, Townsville, Utopia, West Arnhem, Whyalla and Yalata.

From August 2018 through to 30 June 2023, through participating ACCHS, 105,881 syphilis tests were delivered, with an average of 5,294 new tests performed each quarter. Note that data were missing for some services and therefore testing numbers are likely to be an underestimate of all tests delivered. Based on available data, the proportion of people attending a participating ACCHS who received a syphilis test averaged 13% for all individuals in 2022–23, and averaged 23% for the target age group (15–34 years) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b).

Gonorrhoea

Between 2013 and 2022, there was no significant change in the notification rate of gonorrhoea for First Nations people in the 7 jurisdictions included in the analysis (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory) (Table D1.12.5, Figure 1.12.9). Based on age-standardised rates, there was also no statistically significant change in rate of gonorrhoea for First Nations people.

In contrast, the rate for non-Indigenous Australians increased between 2013 and 2022 (annual increase of 6.0 notifications per 100,000 population in the age-standardised rate); however, there was no statistically significant change in the gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians.

Figure 1.12.9: Age-standardised notification rates for gonorrhoea, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2013 to 2022

Source: Table D1.12.5. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

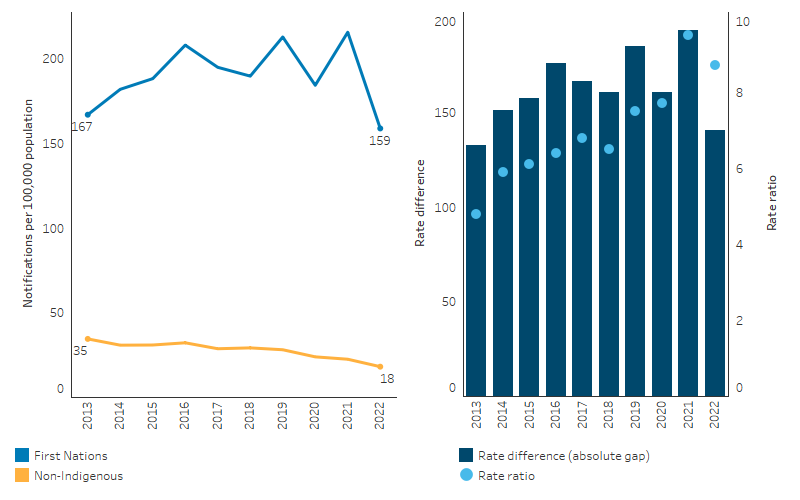

Hepatitis B

Between 2013 and 2022, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory combined, the rate of hepatitis B notifications among First Nations people decreased from 39.9 to 14.1 notifications per 100,000 population (crude rates). Based on linear regression, the rate of hepatitis B notifications among First Nations people declined by an annual average of 2.5 notifications per 100,000 population (Table D1.12.7).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structures between the two populations and over time, the notification rate for First Nations people for hepatitis B decreased by an average of 3.5 notifications per 100,000 population annually, compared with an annual decrease of 0.7 notifications per 100,000 for non-Indigenous Australians. As a result of the larger decrease for First Nations people, the absolute gap in notification rates for hepatitis B between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians narrowed between 2013 and 2022 (by an average of 2.7 notifications per 100,000 population annually) (Table D1.12.7, Figure 1.12.10).

Figure 1.12.10: Age-standardised notification rates for hepatitis B, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2013 to 2022

Source: Table D1.12.7. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

Hepatitis C

Between 2013 and 2021, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory combined, the rate of hepatitis C notifications among First Nations people ranged between 156 per 100,000 population (crude rates) to 205 per 100,000 population. In 2022, the notification rate decreased to 148 per 100,000 population (Table D1.12.6).

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structures between the two populations and over time, there was no statistically significant change in the notification rate for First Nations people for hepatitis C. In contrast, the rate for non-Indigenous Australians decreased between 2013 and 2022 (annual decrease of 1.5 notifications per 100,000 in aged-standardised rates); however, there was no statistically significant change in the gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.6, Figure 1.12.11).

Figure 1.12.11: Age-standardised notification rates for hepatitis C, by Indigenous status, Qld, WA, SA, Tas, ACT and NT, 2013 to 2022

Source: Table D1.12.6. AIHW analysis of National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS) data and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

HIV

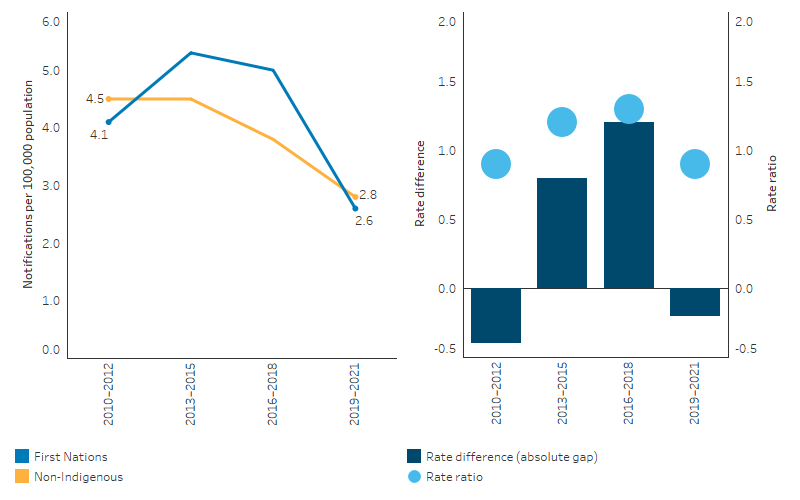

HIV notification rates in the First Nations population are based on relatively small numbers, and changes over time may reflect localised occurrences rather than national patterns (King et al. 2022a).

The HIV notification rate for First Nations people ranged between 3.8 and 4.5 per 100,000 population (crude rates) between 2010–2012 and 2016–2018. In 2019–2021, the notification rate was lower (2.3 per 100,000 population), with these data likely influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Based on age-standardised rates, which adjust for differences in the age structures between the two populations and over time, there was no statistically significant change in HIV notifications for First Nations people between 2010¬–2012 and 2019–2021, or in the gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.12.11, Figure 1.12.12).

Figure 1.12.12: Age-standardised notification rates for HIV, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2010–2012 to 2019–2021

Source: Table D1.12.11. AIHW analysis of National HIV Registry and ABS population estimates and projections ABS 2019, 2022 for calculation of rates.

Research and evaluation findings

First Nations people experience high rates of STIs, particularly in Remote and very remote areas (Department of Health 2018a). Infectious syphilis rates have been exacerbated in Remote and very remote areas by an ongoing outbreak. In 2021, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the First Nations and non-Indigenous populations, the infectious syphilis notification rate for First Nations people in remote areas was more than 77 times as high as the non-Indigenous notification rate, compared with more than 3 times as high in major cities, and more than 6 times as high in regional areas. The notification rates for gonorrhoea and chlamydia in remote areas were also higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians, with rates 24 times and 3 times as high respectively. Remote areas provide particular challenges for sexual health promotion, screening, testing and treatment services which are explored further in the sections below (King et al. 2022b).

Young people’s perspectives on STI risk

A study was conducted based on a national cross-sectional survey of young First Nations people aged 16–29 years between 2011 and 2013. The study found that the majority of study participants had sex for the first time when they were 14 years or younger. There is a strong association between an earlier age at sexual debut and a history of STIs. Earlier onset of sexual activity is also associated with low levels of education, risky sexual behaviours and illicit drug use (Wand et al. 2018).

A review of qualitative research was conducted regarding young First Nations people’s perspectives on sexuality and sexual health, protective factors, and social vulnerability (which arises from interconnected social, cultural, economic, legal and health system-related factors and contributes to negative sexual health outcomes). Findings from the review show that some young First Nations people are practicing a range of harm reduction measures to protect sexual health. Many young women are able to use peer networks for support and to share information. However, many had incomplete knowledge about the transmission and prevention of STIs and were more focused on preventing pregnancy. The dominance and controlling behaviour of young men and the influence of alcohol were negative factors raised in some studies as influencing sexual practice. There was also a clash between Western and First Nations understandings of the body, which can cause confusion when accessing health services. There was evidence of positive family influences and supportive behaviours, but often a lack of inter-generational communication about sexual health issues. The positive role of ACCHSs and other support services in promoting good sexual health was identified, but also a distrust among young First Nations people of services which lacked cultural appropriateness (Bell et al. 2017).

Health Promotion and outreach programs

A 2012 review found that there was limited evidence to support the effectiveness of sexual health education programs for First Nations people, and that few evaluations had been completed (Strobel & Ward 2012). However the evidence available suggested that comprehensive strategies including community education and health promotion are most effective in reducing STIs (Strobel & Ward 2012). Peer education has also been noted as a potential strategy for prevention (MacPhail & McKay 2016).

A more recent study aimed to assess the impacts of the ‘Young Deadly Syphilis Free’ multi-media campaign on both young First Nations people aged 15–34 years and health and community workers across 12 remote Australian regions in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory in 2017–2018. The campaign components encompassed television and radio advertisements, social media posts, and health promotion resources available on a dedicated website. Using a cross-sectional (post-only) evaluation design, data were gathered through online surveys and metrics from social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram. The results indicated that 58% of young people and 75% of health and community workers were aware of the campaign. Key campaign messages were recognised by both groups (> 64%), with television, Facebook, and the website being the primary exposure sources. The campaign positively influenced intended behaviour among young people and professional practices among health and community workers. The study concluded that a multi-media campaign is valuable in raising awareness about syphilis among young First Nations individuals and health professionals in remote areas, suggesting that a prolonged campaign tailored to the diverse needs of remote First Nations youth could optimise campaign impacts to strengthen knowledge and support behavioural change (D'Costa et al. 2022).

A cross-sectional study to explore the uptake of HIV/STI knowledge and safer sex-efficacy in an arts-based sexual health workshop, targeted Northern and Indigenous adolescents in the Northwest Territories (NWT) in Canada. Researchers sought to evaluate the impact of arts-based sexual health workshops on STI knowledge and safer sex efficacy among youth in the NWT. The study utilised a pre- and post-test design, recruiting a convenience sample of students aged 13–18 years from 17 communities. The methodology involved analysing changes in STI knowledge and safer sex efficacy before and after the workshops. The findings revealed statistically significant increases in STI knowledge overall and in safer sex efficacy among participants. Notably, these increases were observed across various demographic and gender groups, including those aged less than 15 years, those in rural communities, those reporting food insecurity, those reporting dating violence, and Indigenous youth. The study identifies the potential of youth-targeted, arts-based sexual health workshops in enhancing STI knowledge and safer sex efficacy among adolescents. However, there were no statistically significant differences in safer sex efficacy observed among participants who were aged 15 or over, sexually active, reporting consistent condom use, and using drugs/alcohol. The study emphasised the need for further research to understand how safer sex efficacy may be influenced by factors such as age, substance use, and sexual experience to inform tailored interventions (Lys et al. 2023).

A small qualitative study in 2 remote Australian communities investigated young First Nations people’s own individual and collective approaches to reducing sexual health risks. In-depth interviews of 35 young First Nations women and men aged 16–21 years revealed individual practices that included: accessing and carrying condoms; having a regular casual sexual partner; being in a long-term trusting relationship; using long-acting reversible contraception; having fewer sexual partners; abstaining from sex; and accessing STI testing. More collective strategies included: refusing sex without a condom; accompanied health clinic visits with a trusted individual; encouraging friends to use condoms and getting STI testing; and providing friends with condoms. Findings signal the need for multi-sectoral STI prevention and sexual health programs driven by young people’s existing harm minimisation strategies and cultural models of collective support and training to help health professionals to support young people in building on these existing strengths. Specific strategies to enhance young people’s sexual health include: peer condom distribution; accompanied health service visits; peer-led health promotion; continued community-based condom distribution; enhanced access to a fuller range of available contraception in primary care settings; engaging health service-experienced young people as ‘youth health workers’ (Bell et al. 2020b).

Socio-ecological analysis of factors influencing young First Nations people’s willingness to undertake testing for STIs within clinics in Australia found that strategies to improve uptake of STI testing must tackle the overlapping social and health service factors that discourage young people from seeking sexual health support. Much can be learned from young people’s lived sexual health experiences and family and community-based health promotion practices (Bell et al. 2020a).

The Deadly Liver Mob (DLM) is a peer-delivered incentivised health promotion program by and for First Nations people. The program aims to increase access to bloodborne virus (BBV) and STI education, screening, treatment, and vaccination for First Nations people in recognition of the systemic barriers for First Nations people to primary care, including BBV- and STI-related stigma, and institutional racism. The evaluation of the DLM presents routinely collected data across 9 sites in New South Wales on the ‘cascade of care’ progression of First Nations clients through the DLM program: hepatitis C education, screening, returning for results, and recruitment of peers. The DLM program shows promise in acting as a ‘one stop shop’ in addressing the needs of First Nations people in relation to BBVs and STIs. Future implementation could focus on addressing any potential barriers to participation in the program, such as co-location of services and transportation (Cama et al. 2023).

Screening, testing and health care responses

A systematic review of the impact of STI programs delivered by primary health-care (PHC) centres in remote First Nations communities found 12 evaluations of 4 programs delivered in South Australia, the Northern Territory and Western Australia (Guy et al. 2012). There was some evidence of success in 3 of the 4 programs, indicating that clinical best practice and well-coordinated sexual health programs can reduce chlamydia and gonorrhoea prevalence in remote First Nations communities. Interpretation of the findings was limited by a lack of systematic reporting of program indicators, and other potential confounding factors. The authors identified characteristics of a comprehensive approach to STI control which although resource intensive, will reduce STI prevalence, and encompassed: regular screening; timely treatment; partner notification; staff training; health education and promotion; disease surveillance; and monitoring and evaluation. Many other factors are likely to play a role in the success of an STI program including the retention of staff, recruitment of health-care workers with the appropriate gender, the variability in the types of health promotion programs undertaken in remote settings, young people’s access to health services, and historical and contemporary issues that impact on health service delivery between communities and health service providers.

Nattabi et al. (2017) examined the extent of variation in delivery of recommended STI screening investigations and counselling within Aboriginal PHC centres (both government and community-controlled, across 5 jurisdictions and across urban, regional and remote settings). The study used data from preventive health audits conducted at 137 Aboriginal PHC centres participating in the Audit and Best Practice for Chronic Disease (ABCD) Program over the period 2005–2014. The ABCD program supports systematic continuous quality improvement (CQI) in services. The study found:

- there are significant variations in STI testing and counselling among Aboriginal PHC centres. A number of Aboriginal PHC centres were achieving high rates of STI testing and counselling, while a significant number were not;

- there were positive associations between the provisions of both adult health checks and Pap tests, and higher levels of STI testing and counselling for female clients (more women were screened for STIs in conjunction with Pap tests and following conversations about contraception). The study noted that the move to 5 yearly HPV testing in 2017 could therefore impact STI testing rates among female clients;

- women were benefitting from more STI screening as a result of their particular health seeking behaviours, and having good access to culturally appropriate care delivered by female health workers in regional and remote Australia;

- there were a significant number of health centres with relatively low documented evidence of adherence to best practice; and

- several areas of improvement for services, with analysis showing that variations in STI related service delivery were mainly attributed to health centre factors (such as duration of participation in the CQI project, providing adult health checks and Pap tests) rather than client factors (Nattabi et al. 2017).

A randomised crossover trial was conducted from 2013 to 2016 to assess the efficacy of a point of care molecular test for chlamydia and gonorrhoea among First Nations people attending Australian remote primary health services. The trial recruited primary health services in Western Australia, Far North Queensland, and South Australia that provide care to First Nations people in regional or remote locations. The primary outcome was the proportion of people (aged 16–29 years) found to have chlamydia or gonorrhoea who had a positive result at retesting 3 weeks to 3 months after treatment (Guy et al. 2018). Molecular point-of-care tests can provide rapid results which make it easier to quickly treat positive cases – some of whom would not otherwise receive treatment. The findings showed that time to treatment could be substantially reduced by the use of molecular point-of-care tests, but retesting rates were too low to draw conclusions about the impact on reinfection rates.

A Queensland population-based study of 1,107,233 women, aged 20–69 years who underwent cervical screening (or previously the Pap test) between 2013 and 2017 identified factors associated with regional variation in First Nations women receiving Pap tests. The study found that North Queensland, where there is a greater population coverage of PHC (including ACCHSs), had a much higher rate of Pap test screening of First Nations women than among First Nations women in the rest of Queensland. This study indicates that access to ACCHSs may explain at least part of the regional variation in cervical screening participation for First Nations women in Queensland. Improving access to PHC, especially through ACCHSs may reduce existing disparities in cervical screening participation (Dasgupta et al. 2021).

A secondary analysis of interview data of health care providers and managers collected as part of the BBV & STI Research, Intervention and Strategic Evaluation Aboriginal Systems Project (BRISE ASP) in 2016 clearly identified that the offering of STI testing to all young people attending a service as part of routine health care was an effective mechanism to circumvent shame and stigma that can act as a barrier to testing. Systematic efforts to normalise STI testing within services were recognised as drivers of increased acceptability and uptake among the target population. The MBS item 715, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples health assessment, for the adult cohort (15–54 years), does require the consideration of the need for examination for STIs. This includes urine or endocervical swab for chlamydia and gonorrhoea especially among those aged 15 to 35 years. Participants in the interviews strongly recommended incorporating standardised STI test sets into MBS item 715 as a best practice strategy for integrating STIs into routine care within the ACCHS setting (McCormack et al. 2022).

An independent evaluation of NACCHO’s role under the Enhanced Syphilis Response (ESR) Program (2017–18 to 2020–21), concluded the ESR model may serve as a blueprint for how the Government can achieve broader positive health outcomes for First Nations people, including by harnessing the leadership role played by NACCHO across the community-controlled health sector. The evaluation found the approach to co design, collaboration and partnership, and the inclusive, flexible and responsive project management style were integral to stabilising infectious syphilis in outbreak areas. The resulting trust and relationship between ESR stakeholders also contributed to the seamless transition into managing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on First Nations communities (Equity Economics 2021). For more on the response to the syphilis outbreak see the Implications section of this Measure.

A study explored the barriers and facilitators to hepatitis C virus treatment for First Nations people in rural South Australia as viewed from a health care provider perspective in the era of direct acting antivirals (DAAs). The study was conducted using 2 methods including a qualitative systematic review examining the barriers and enablers to diagnosis and treatment among indigenous peoples living with hepatitis C worldwide; and a qualitative descriptive study with health care workers from 6 de-identified rural and regional ACCHSs in South Australia. The results from both the international systematic review and the study of South Australian health care workers were integrated at the analysis phase to understand how hepatitis C treatment could be improved for rural First Nations people. This study explored barriers at the individual, provider, and system levels, especially stigma and shame which impact multiple aspects of care including prevention, management, and treatment. Key implications for public health policy included emphasising culturally appropriate hepatitis C education for clients, the community, and health service providers. Continued efforts to facilitate the uptake of DAA medications for First Nations people in rural and remote areas should use a multifaceted approach to provide education to clinicians and the community, increasing hepatitis C knowledge and cultural awareness, and aiding in reducing stigma and discrimination (Lim et al. 2023).

Implications

Meeting and exceeding international obligations and targets are a critical part of Australia’s response to STIs. Internationally, Australia supports the World Health Organization’s Global Health Sector Strategy on Sexually Transmitted Infections 2016–2021, which has an overarching goal of ending sexually transmissible infection epidemics as major public health concerns. STIs are a major health problem for First Nations people in Australia. Bacterial STIs are treatable through antibiotics, but if left untreated can have significant health consequences (Australasian Sexual Health Alliance 2017). A range of access issues have been identified for health care (see measure 3.14 Access to services compared with need) and shame has been found to be an additional factor for STIs (MacPhail & McKay 2016).

First Nations people are disproportionately impacted by STIs compared with the non-Indigenous population. Lack of access to testing and treatment and complex social and medical factors mean that First Nations people are more frequently exposed to environments and situations where there is an increased risk of exposure to STIs and are therefore disproportionately impacted (King et al. 2022a). High rates of infection for First Nations people highlight the need for targeted prevention, along with opportunistic testing (Fairley & Hocking 2012; Graham et al. 2015; O'Connor et al. 2014).

There is a critical and ongoing need to identify and address the barriers experienced by First Nations people in accessing STI prevention, testing, treatment and support services. The implementation of targeted approaches using culturally appropriate education, prevention, testing, treatment and care programs are imperative. This includes culturally inclusive and safe approaches which are tailored for people from remote, rural, regional and urban areas, women, people who are highly mobile, people who use drugs, people with complex needs and people in custodial settings. Young people continue to experience a significant burden of STIs in Australia. There is also a disproportionate burden of STIs among First Nations people, who experience notification rates many times that of the non-Indigenous population. A review has found young First Nations people display similar risk-taking and health-seeking behaviours to non-Indigenous young people, suggesting that a lack of accessibility of services is a key issue in STI management for First Nations youth. Barriers faced by young First Nations people in accessing health services include stigma, shame, confidentiality concerns and the absence of age-responsive or culturally responsive services. A lack of access to both male and female health professionals across the clinical workforce limits the ability of young people to access professionals of the appropriate gender and can impact on their engagement with services (Bell et al. 2017; MacPhail & McKay 2016; Wand et al. 2016).

The ongoing syphilis outbreak in northern and central Australia is of particular concern. A nationally coordinated enhanced response is currently underway to control this outbreak by addressing barriers and collectively developing sustainable solutions. This enhanced response also provides an opportunity to address other BBVs and STIs (Department of Health 2018a).

In 2017, the NACCHO began working with ACCHSs and state and territory affiliates to raise awareness of the syphilis outbreak among Australian Government, and state and territory governments. NACCHO’s leadership resulted in the Australian Government funding the $21.2 million Enhanced Syphilis Response (ESR) Program (2017–18 to 2020–21) to support ACCHSs provide locally appropriate and culturally safe services in outbreak regions. Under this program, NACCHO was tasked with coordinating the roll-out of the response in partnership with its member ACCHSs in declared outbreak regions. ESR funding has been used to employ additional staff; provide staff with training to undertake syphilis point-of-care testing; support the development and delivery of culturally safe community education, engagement and health promotion resources; and for the purchase of testing equipment and supplies. Additionally, the creation of a community of practice (ESR Network) has provided access to a cohort of committed and highly experienced Aboriginal Health champions to support staff at new participating ACCHSs to establish their own syphilis programs. They share their experiences and lessons learned, clinical protocols and health promotion strategies. They also provide new staff with the confidence to address the stigma commonly associated with syphilis (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

The Fourth National STI Strategy 2018–2022 provides the guiding principles, goals, targets, priority areas and priority populations for the national approach to addressing STIs (Department of Health 2019). Together with the National STI Strategy, the National Strategic Approach for Responding to Rising Rates of Syphilis in Australia 2021 guides the national response. The National Syphilis Surveillance and Monitoring Plan 2021 provides indicators to monitor progress towards achieving 3 targets (reducing the incidence of syphilis; eliminate congenital syphilis; control outbreaks among First Nations people in Queensland, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia). The Australian Government reports on progress through the National syphilis surveillance quarterly reports.

The Australian Government is addressing the high rates of STIs and BBVs among First Nations people and communities through the:

- National strategic approach for an enhanced response to the disproportionately high rates of STI and BBV in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Department of Health 2018a); and

- Action plan – Enhanced response to addressing STI (and BBV) in Indigenous populations (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022).

The objectives of the strategic approach (and supported by the Action Plan) are to:

- control the syphilis outbreak in northern and central Australia

- undertake opportunistic control efforts for other STIs and BBVs

- consider the long-term sustainable response to STI and BBV issues for First Nations people.

The strategic approach and action plan were developed by the governance group of the Australian Health Protection Principal Committee and endorsed by the Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council.

The increase in hepatitis C notification rates may be showing signs of slowing, however, rates remain very high. Improved access to culturally responsive education, needle and syringe programs and evidence-based opioid treatment programs (OTP), as well as improved diagnosis and treatment rates, are all critical aspects of the response to hepatitis C. This highlights the importance of equitable access to DAA treatment and evidence-based harm reduction, including culturally respectful and safe needle and syringe programs (NSPs), for this population as key actions (Department of Health 2018a). The Fifth National Hepatitis C Strategy 2018–2022, seeks to revitalise efforts in education and awareness, and in encouraging early treatment, testing and continued care (Department of Health 2018b).

Hepatitis B is associated with significant morbidity and mortality; therefore, it is essential that access to appropriate services for the management of chronic hepatitis B is available for First Nations people. Improvement in the notification rate for hepatitis B is encouraging, with high vaccination rates among First Nations children. However, ongoing effort is required particularly among middle and older age groups with chronic hepatitis B, who need regular testing and treatment to prevent the development of liver cancer.

First Nations people in Australia remain disproportionately vulnerable to HIV due to factors such as high rates of STIs, poorer general health, high levels of injecting drug use and also unique challenges in accessing HIV treatment and care (Bryant et al. 2016; Templeton et al. 2015). Access to testing and treatment is essential to prevent the development of AIDS and associated morbidities, achieve viral suppression, enhance individual health outcomes and prevent onward HIV transmission.

The Fifth National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Blood-Borne Viruses and Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2018–22 was published in 2018 (Department of Health 2018a). This is one of a set of 5 national strategies that together outline a framework for a high-quality and coordinated national response to BBVs and STIs in Australia. First Nations young people aged 15 to 29 and people living in remote areas have been identified as a priority group in the Strategy, which recognises that young people are disproportionately affected by BBVs and STIs and need special consideration in the national response.

The ACCHS sector, including services and support organisations, and broader community organisations at the national, state and territory level are central to the partnership approach espoused by the Fifth Strategy. They continue to play a vital role in the national response through coordination, capacity building, resource development and provision, policy translation and being a facilitator between government and priority First Nations sub-populations (Department of Health 2018a).

An achievement of previous strategies was to increase testing. This may have contributed to the increases seen in notifications for some STIs and BBVs. However, under-identification of First Nations people and the volatility in small numbers means that caution should be used in interpreting short-term trends in these data.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 - 2031. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2022. National, state and territory population, Reference Period December 2022. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2024. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander births and confinements, summary, by state. Canberra. Viewed 11/01/2024.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2022a. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on disease burden among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed October 2023.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. AIHW, Australian Government.

- Australasian Sexual Health Alliance 2017. Australian STI Management Guidelines for use in Primary Care. ASHA. Viewed 21 July 2020.

- Bell S, Aggleton P, Ward J & Maher L 2017. Sexual agency, risk and vulnerability: a scoping review of young Indigenous Australians’ sexual health. Journal of Youth Studies 20:1208-24.

- Bell S, Aggleton P, Ward J, Murray W, Silver B, Lockyer A et al. 2020a. Young Aboriginal people's engagement with STI testing in the Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Public Health 20:459-.

- Bell S, Ward J, Aggleton P, Murray W, Silver B, Lockyer A et al. 2020b. Young Aboriginal people's sexual health risk reduction strategies: a qualitative study in remote Australia. Sex Health 17:303-10.

- Bowden FJ, Tabrizi SN, Garland SM & Fairley CK 2002. MJA Practice Essentials — Infectious Diseases Chapter 6: Sexually transmitted infections: new diagnostic approaches and treatments. Med J Aust 176:551-7.

- Bryant J, Ward J, Wand H, Byron K, Bamblett A, Waples-Crowe P et al. 2016. Illicit and injecting drug use among Indigenous young people in urban, regional and remote Australia. Drug & Alcohol Review 35:447-55.

- Cama E, Beadman K, Beadman M, Smith K-A, Christian J, Jackson AC et al. 2023. Increasing access to screening for blood-borne viruses and sexually transmissible infections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: evaluation of the Deadly Liver Mob program’s ‘cascade of care’ across nine sites in New South Wales, Australia. Harm reduction journal 20:1-125.

- Campbell S, Lynch J, Esterman A & McDermott R 2011. Pre-pregnancy predictors linked to miscarriage among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women in North Queensland. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 35:343-51.

- Cohen MS 1998. Sexually transmitted diseases enhance HIV transmission: no longer a hypothesis. The Lancet 351:S5-S7.

- D'Costa B, Lobo R, Sibosado A, Leavy JE, Crawford G & Ward J 2022. Evaluation of the Young, Deadly, Syphilis Free multi-media campaign in remote Australia. PloS one 17:e0273658-e.

- Dasgupta P, Condon JR, Whop LJ, Aitken JF, Garvey G, Wenitong M et al. 2021. Access to Aboriginal Community-Controlled Primary Health Organizations Can Explain Some of the Higher Pap Test Participation Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women in North Queensland, Australia. Front Oncol 11:725145.

- Department of Health 2014. Fourth National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Blood-borne Viruses and Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2014–2017. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Health 2018a. Fifth National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Blood Borne Viruses and Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2018–2022. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

Department of Health 2018b. Fifth National Hepatitis C Strategy. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia. - Department of Health 2019. Fourth National Sexually Transmissible Infections Strategy 2018-2022. Commonwealth of Australia: Department of Health.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2021. The new National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Viewed December 2023.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2022. Action plan – Enhanced response to addressing sexually transmissible infections (and bloodborne viruses) in Indigenous populations. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of health and Aged Care 2023a. National Syphilis Surveillance Quarterly Report Quarter 3: 1 JULY – 30 SEPTEMBER 2023 Canberra.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b. National syphilis surveillance report - April to June 2023. Department of Health and Aged Care. Viewed 10 October 2023.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2023c. National syphilis surveillance quarterly report 2024. Syphilis. Viewed 7/02/2024.

- Equity Economics 2021. Blueprint for the Future: Evaluation of NACCHO’s Role under the Enhanced Syphilis Response. A Report prepared for the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO).

- Fairley CK & Hocking JS 2012. Sexual health in Indigenous communities. Med J Aust 197:597-8.

- Graham S, Guy R, Ward J, Kaldor J, Donovan B, Knox J et al. 2015. Incidence and predictors of annual chlamydia testing among 15–29 year olds attending Aboriginal primary health care services in New South Wales, Australia. BMC Health Services Research 15:437.

- Guy R, Ward J, Causer L, Natoli L, Badman S, Tangey A et al. 2018. Molecular point-of-care testing for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in Indigenous Australians attending remote primary health services (TTANGO): a cluster-randomised, controlled, crossover trial. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 18:1117-26.

- Guy R, Ward J, Smith K, Su J, Huang R, Tangey A et al. 2012. The impact of sexually transmissible infection programs in remote Aboriginal communities in Australia: a systematic review. Sex Health 9:205-12.

- HealthDirect 2022. Hepatitis C. Viewed 10 October 2023.

- King J, McManus H, Kwon A, Gray R & McGregor S 2022a. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia: Annual surveillance report 2022. Sydney, Australia: The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney.

- King J, Naruka E, Thomas J, McManus H & McGregor S 2022b. Blood borne viral and sexually transmissible infections in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Annual surveillance report. Sydney, Australia: The Kirby Institute, UNSW Sydney. Viewed 19 December 2023.

- Lim D, Phillips E, Bradley C & Ward J 2023. Barriers and Facilitators to Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Treatment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in Rural South Australia: A Service Providers' Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20:4415.

- Lys C, Logie CH, Mackay KI, MacNeill N, Loppie C, Gittings L et al. 2023. Exploring uptake of HIV/STI knowledge and safer sex-efficacy in an arts-based sexual health workshop among Northern and Indigenous adolescents in the Northwest Territories, Canada. AIDS Care 35:411-6.

- MacLachlan JH, Allard N, Towell V & Cowie BC 2013. The burden of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Australia, 2011. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 37:416-22.

- MacPhail C & McKay K 2016. Social determinants in the sexual health of adolescent Aboriginal Australians: a systematic review. Health & Social Care in the Community.

- McCormack H, Guy R, Bourne C & Newman CE 2022. Integrating testing for sexually transmissible infections into routine primary care for Aboriginal young people: a strengths‐based qualitative analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 46:370-6.

- O'Connor C, Ali H, Guy R, Templeton D, Fairley C, Chen M et al. 2014. High chlamydia positivity rates in Indigenous people attending Australian sexual health services. Med J Aust 200:595-8.

- Otu A, Danhoundo G, Toskin I, Govender V & Yaya S 2021. Refocusing on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) to improve reproductive health: a call to further action. Reprod Health 18:242-.

- Sankaran D, Partridge E & Lakshminrusimha S 2023. Congenital Syphilis-An Illustrative Review. Children (Basel) 10.

- Starrs AM, Ezeh AC, Barker G, Basu A, Bertrand JT, Blum R et al. 2018. Accelerate progress—sexual and reproductive health and rights for all: report of the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission. Lancet 391:2642-92.

- Strobel NA & Ward J 2012. Education programs for Indigenous Australians about sexually transmitted infections and bloodborne viruses. (ed., Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Templeton DJ, Wright ST, McManus H, Lawrence C, Russell DB, Law MG et al. 2015. Antiretroviral treatment use, co-morbidities and clinical outcomes among Aboriginal participants in the Australian HIV Observational Database (AHOD). BMC Infectious Diseases 15:326.

- Wand H, Bryant J, Worth H, Pitts M, Kaldor J, Delaney-Thiele D et al. 2018. Low education levels are associated with early age of sexual debut, drug use and risky sexual behaviours among young Indigenous Australians. Sexual health 15:68-75.

- Wand H, Ward J, Bryant J, Delaney-Thiele D, Worth H, Pitts M et al. 2016. Individual and population level impacts of illicit drug use, sexual risk behaviours on sexually transmitted infections among young Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: results from the GOANNA survey. BMC Public Health 16:600.

- World Health Organization 2019. Q&A Detail: What is hepatitis? Viewed 7 August 2020.

- World Health Organization 2020. HIV/AIDS. Viewed 7 August 2020.