Key messages

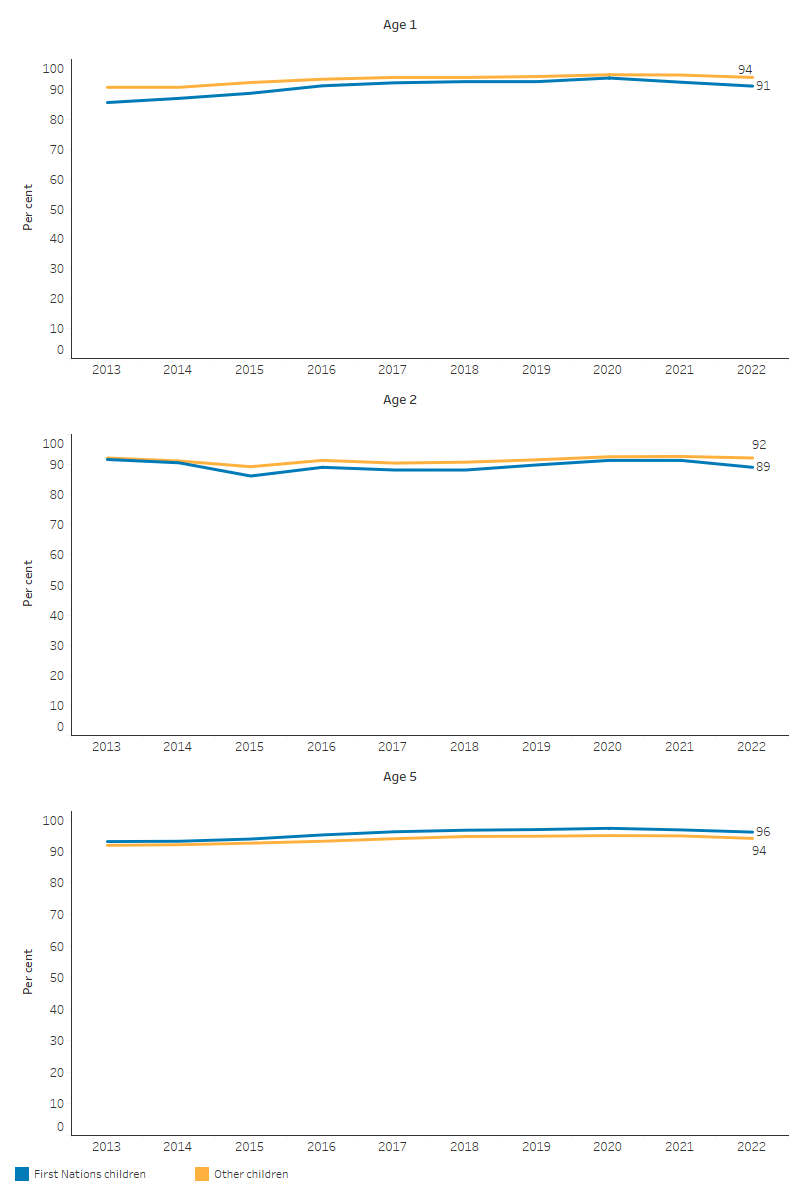

- In 2022, based on data from the Australian Immunisation Register (AIR), the proportions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) children aged 1, 2 and 5 who were fully immunised were 91%, 89% and 96%, respectively. Of concern, the proportion of First Nations children who were fully immunised decreased between 2020 and 2022, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic – this will be explored further in future reports.

- Between 2013 and 2022, the proportion of First Nations children aged 1 who were fully immunised increased from 86% in 2013 to a peak of 94% in 2020 before declining to 91% in 2022. A similar pattern was seen for First Nations children aged 5, where the proportion who were fully immunised increased from 93% in 2013 to 97% in 2020 and then declined to 96% in 2022.

- In 2022, Tasmania had the highest rates of immunisation coverage for First Nations children (between 95% and 98%, depending on age), while Western Australia had the lowest (between 82% and 94%).

- Between 2013 and 2022, the proportion of fully immunised First Nations children at age 5 consistently exceeded that of other children. The gap in immunisation coverage between First Nations and other Australian children aged 1 narrowed between 2013 and 2022.

- In 2022, 83% of First Nations girls had completed a full dose of human papillomavirus virus (HPV) vaccine by 15 years of age, compared with 85% of all Australian girls. Among First Nations boys, 78% had completed a full dose of the HPV vaccine by 15 years of age, compared with 83% of all Australian boys.

- As at 12 April 2024, based on data from the AIR, 18,100 (3.6%) First Nations adults had received a COVID-19 vaccination within the previous 6 months, 418,800 (82.4%) had received a vaccination 6 or more months ago, and 71,500 (14.1%) were unvaccinated.

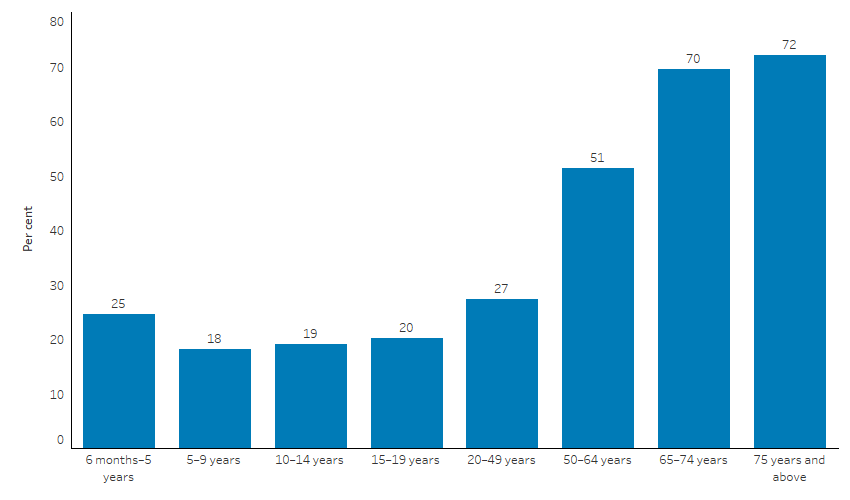

- Infants and children aged under 5 have a higher risk of hospitalisation and increased risk of complications from influenza. One-quarter (25%) of First Nations children aged from 6 months to under 5 years had received an influenza vaccination in 2022. Older people are also at higher risk. In 2022, 51% of First Nations people aged 50–64, 70% of those aged 65–74, and 72% of those aged 75 and over had an influenza vaccination.

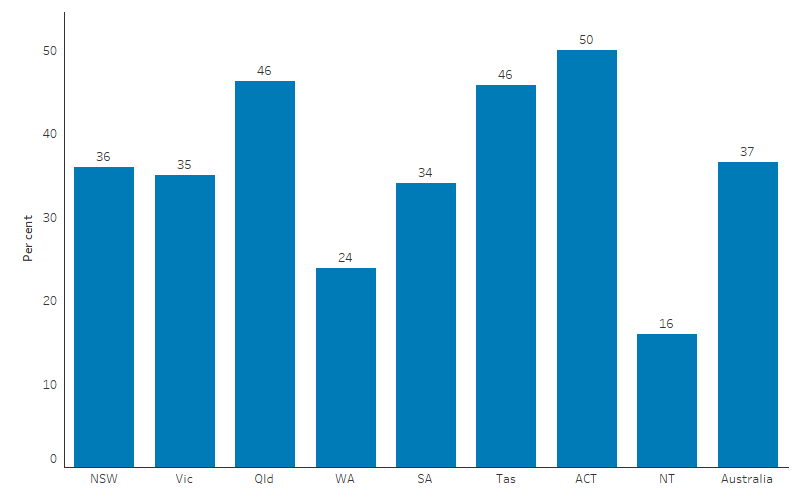

- People who experienced chickenpox as a child are at risk of developing shingles (also called herpes zoster) as an adult. Shingles can cause severe pain and illness. Vaccination is effective at preventing infection and complications. Among First Nations people turning 71 years of age in 2022, 37% were vaccinated for shingles. Coverage across states and territories ranged from 16% in the Northern Territory to 50 % in the Australian Capital Territory.

- Among First Nations people turning 71 years of age in 2022, 38% had been vaccinated against pneumococcal disease – an increase from 25% in 2021.

- Multiple studies have found that personalised and culturally appropriate communication methods, such as personalised calendars, SMS reminders, pre-call services and letters have proven effective in improving immunisation rates and timeliness among First Nations children. In contrast, less personalised methods like pamphlets are less impactful.

Why is it important?

Immunisation is highly effective in reducing illness and death caused by vaccine-preventable diseases. Childhood vaccination for diphtheria was introduced in Australia in 1932 and the use of vaccines to prevent tetanus, pertussis (whooping cough) and poliomyelitis became common in the 1950s. This was followed by vaccines for measles, mumps and rubella in the 1960s, and later vaccines for hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenza type b, varicella (chicken pox), pneumococcal disease, meningococcal C, rotavirus, human papillomavirus (HPV) and influenza.

Deaths from vaccine-preventable diseases have fallen for the general population by 99% since the introduction of childhood vaccinations – it is estimated that vaccinations have saved around 78,000 lives between 1932 and 2003 (Burgess 2003). Internationally, vaccinations have been effective in reducing the disease disparities between indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, despite differences in the socioeconomic circumstances of these populations (Menzies & Singleton 2009).

Vaccinations are necessary not only in childhood; pregnant and post-partum women are subject to high risk from severe illness and complications from influenza, and maternal vaccination is shown to protect mothers and infants from illness (Overton et al. 2016). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) adults may be at increased risk of severe illness resulting from influenza and invasive pneumococcal disease due to other risk factors and comorbidities. Programs to make these vaccines accessible have led to improved vaccination rates.

First Nations people also experience a range of pre-existing health risks and social disadvantage that increase the risk of severe illness or death if infected with COVID-19 when compared with non-Indigenous Australians. First Nations people have higher prevalence of chronic conditions, such as respiratory diseases, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases, which are known to increase the risk of severe illness and death from COVID-19. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the need for swift action to ensure implementation of equitable and appropriate prevention, treatment, and management measures to vulnerable population groups (Yashadhana et al. 2020).

COVID-19 highlighted the unique capacity of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) to respond rapidly and effectively in a national health crisis. Well before the pandemic was declared by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the sector had mobilised. The partnership between the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and the Australian Government was critical in supporting First Nations communities across Australia to develop local plans. It built on a pre-existing relationship that had effectively responded to syphilis outbreaks (Department of Health 2021). A review of the efficacy of COVID-19 pandemic responses heralded First Nations communities in Australia as an exemplary demonstration of how self-determination can achieve optimal health outcomes for First Nations peoples (Dudgeon et al. 2023). Making space for First Nations peoples to define the issues, determine the priorities and suggest solutions for culturally informed strategies that address local community needs is a way to reduce health inequities and has the potential to influence system changes (Crooks et al. 2020).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around four Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including through working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community-controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision making by First Nations communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations health and wellbeing and is the first national health plan to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement.

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

Childhood immunisation coverage

The Australian Immunisation Register (AIR) is a national register that details all funded vaccinations and most privately purchased vaccines given to individuals of all ages who live in Australia. It was set up in 1996 as the Australian Childhood Immunisation Register and renamed following its expansion in 2016 to allow inclusion of information on adult vaccinations.

According to the National Immunisation Program Schedule, Australian children are expected to have received specific immunisations by age 1, 2 and 5. As at December 2022, slightly lower proportions of First Nations children were fully immunised at age 1 and 2 than other children; however, at age 5 the proportion was higher for First Nations children than other Australian children. Based on AIR data, the proportion of children who were fully immunised:

-

at age 1, was 91% for First Nations children, compared with 94% for other children

-

at age 2, was 89% for First Nations children, compared with 92% for other children

-

at age 5, was 96% for First Nations children and 94% for other children (Table D3.02.1, Figure 3.02.1).

‘Other children’ includes non-Indigenous children and those whose Indigenous status was not reported (see Data sources: Australian Immunisation Register).

Across states and territories, the proportion of First Nations children who were fully immunised at age 1 varied from 87% in Western Australia to 96% in Tasmania. Similarly, the proportion of First Nations children aged 2 and 5 who were fully immunised was lowest in Western Australia (82% at age 2, 94% at age 5), and highest in Tasmania (95% at age 2, 98% at age 5) (Table 3.02-1).

Table 3.02-1: Proportion of children fully immunised at age 1 year, 2 years and 5 years, by Indigenous status and jurisdiction, 2022

|

Jurisdiction |

First Nations children (1 year) |

Other children (1 year) |

First Nations children (2 years) |

Other children (2 years) |

First Nations children (5 years) |

Other children (5 years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | 93.1 | 93.8 | 91.2 | 92.0 | 96.9 | 94.0 |

| VIC | 91.6 | 94.0 | 89.6 | 92.6 | 95.6 | 95.0 |

| Qld | 90.3 | 93.5 | 89.4 | 91.9 | 96.0 | 93.2 |

| WA | 86.8 | 94.1 | 82.2 | 91.8 | 94.4 | 93.2 |

| SA | 91.3 | 94.7 | 90.1 | 92.5 | 96.8 | 95.5 |

| Tas | 96.4 | 94.2 | 94.5 | 91.6 | 97.7 | 94.1 |

| ACT | 92.5 | 96.6 | 89.8 | 95.0 | 97.0 | 95.7 |

| NT | 87.9 | 95.9 | 84.4 | 92.9 | 94.9 | 93.1 |

| Australia | 91.1 | 94.0 | 89.1 | 92.2 | 96.1 | 94.1 |

Note: Other children include non-Indigenous children and those whose Indigenous status is unknown.

Source: Tables D3.02.2, D3.02.3 & D3.02.4. AIHW analysis of the Australian Immunisation Register.

Change over time in childhood vaccination

Between 2013 and 2022, there were statistically significant increases in the proportion of First Nations children aged 1 and 5 who were fully immunised. There was no statistically significant change in the proportion of First Nations children aged 2 who were fully immunised over the decade from 2013 to 2022, though this may be affected by an increase in the number of vaccines scheduled for this age group during the time period.

While there was an overall improvement in immunisation coverage over the decade for First Nations children aged 1 and 5, there were decreases in coverage rates between 2020 and 2022, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. For First Nations children aged 2, the coverage rate was the same in 2021 as in 2020, though it dropped in 2022.The recent decline in childhood vaccination coverage in these age cohorts is of concern and will be explored further in future reports as more data become available.

Between 2013 and 2022, the proportion of First Nations children aged 1 who were fully immunised increased from a low of 86% in 2013 to a peak of 94% in 2020 before declining by 3 percentage points to 91% in 2022. A similar pattern was seen for First Nations children aged 5, where the proportion who were fully immunised increased from 93% in 2013 to 97% in 2020 and then declined to 96% in 2022. Similarly, among other children aged 1 and 5, the proportion who were fully immunised increased between 2013 (91% and 92%, respectively) and 2022 (both 94%), peaking in 2020 (both 95%) (Table D3.02.5, Figure 3.02.1).

For First Nations children aged 2, over the period 2013 to 2022, the proportion who were fully immunised ranged between 86.2% (in 2015) and 91.7% (in 2013), with no trend apparent. In 2022, 89.1% of First Nations children were fully immunised – about 2 percentage points lower than in 2020 and 2021 (91.4% in both years) (Table D3.02.5, Figure 3.02.1).

The gap in immunisation coverage between First Nations and other children aged 1 narrowed between 2013 and 2022. There was no statistically significant change in the gap for children aged 2. The proportion of fully immunised First Nations children at age 5 consistently exceeded that of other children over the period from 2013 to 2022 (Table D3.02.5, Figure 3.02.1).

Figure 3.02.1: Proportion of children fully immunised at age 1, 2 and 5, by Indigenous status, 2013 to 2022

Note: The age at which older children are assessed changed from 6 years to 5 years in 2007 and comparisons of trends over time are affected by the introduction of new vaccines on the schedule.

Source: Table 3.02.5. AIHW analysis of data from the Australian Immunisation Register.

Human papillomavirus vaccination coverage among adolescents

Human papillomavirus virus (HPV) is a viral infection that is sexually transmitted and can cause cancers and genital warts. The HPV vaccine is free under the National Immunisation Program (NIP) for young people aged around 12 to 13, primarily provided through school immunisation programs, though adolescents who missed the HPV vaccination at 12 to 13 years of age can catch up for free up to age 26 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023).

In 2022, 83% of First Nations girls had received a full dose of the HPV vaccine by 15 years of age, as had 78% of First Nations boys (Table 3.02-2) (NCIRS 2023). These HPV coverage rates were lower than among all Australian girls and boys at age 15 (85% of all girls, and 83% of all boys). Comparisons are made with all Australians (which includes First Nations people as well as other Australians) due to data availability (see data sources: Australian Immunisation Register).

HPV coverage rates were higher among First Nations adolescents living in Major cities compared with those residing elsewhere. Among First Nations girls, 85% of those living in Major cities received the HPV vaccine in 2022, followed by 83% in Inner and outer regional areas, and 78% in Remote and very remote areas. For First Nations boys, the rates were 80% in Major cities and 77% in Inner and outer regional areas and 77% in Remote and very remote areas (Table D3.02.11) (NCIRS 2023).

Based on the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Economic Resources (see also measure 2.09 Socioeconomic indexes), the rate of HPV vaccination was generally higher among individuals living in areas with a higher advantage in socioeconomic status. In 2022, this trend was observed for both First Nations girls, with 79% in the least advantaged area compared with 89% in the most advantaged area, and boys, with 75% compared with 83% (Table D3.02.11) (NCIRS 2023). Across states and territories, the HPV vaccination rate among First Nations girls by age 15 was lowest in South Australia at 75%, and highest in the Australian Capital Territory at 89%. For First Nations boys by age 15, the coverage rate ranged from 66% in South Australia to 83% in the Australian Capital Territory (Table 3.02-2).

The difference in HPV vaccination coverage rates for First Nations adolescents by age 15 compared with the state average for all adolescents was largest in South Australia (difference of 10.5 percentage points for girls, and 17.7 percentage points for boys). The smallest differences were in Tasmania (0.6 percentage point difference for girls, with a higher rate for First Nations girls, and 0.8 percentage points for boys) (Table D3.02.11).

Table 3.02-2: HPV vaccination coverage for girls and boys by 15 years of age, by Indigenous status and jurisdiction, 2022

|

Jurisdiction |

First Nations girls |

All girls |

First Nations boys |

All boys |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSW | 88.1 | 86.7 | 81.7 | 84.2 |

| VIC | 82.5 | 86.8 | 78.8 | 82.4 |

| Qld | 80.3 | 82.4 | 76.4 | 80.5 |

| WA | 81.4 | 84.5 | 78.6 | 83.1 |

| SA | 74.6 | 85.1 | 65.6 | 83.3 |

| Tas | 84.6 | 84.0 | 79.5 | 80.3 |

| ACT | 88.5 | 89.8 | 82.7 | 87.5 |

| NT | 78.4 | 81.6 | 75.2 | 78.3 |

| Australia | 83.0 | 85.3 | 78.1 | 83.1 |

Notes:

1. Coverage calculated using the number of Medicare-registered adolescents in each year-wide birth cohort with an AIR record of having received at least one dose of HPV vaccine after their 9th birthday (since HPV is registered to be given from 9 years of age) but before their 15th birthday as the numerator and the total number of Medicare-registered adolescents in the relevant birth cohort as the denominator, expressed as a percentage.

2. ‘By 15 years of age’ refers to cohort born 1 January–31 December 2007 for 2022 coverage estimates (vaccines due from early 2019 to late 2020).

3. All girls/boys includes both First Nations and non-Indigenous children, and those whose Indigenous status is unknown.

Source: Table D3.02.11, based on Australian Immunisation Register data as at 2 April 2023 (NCIRS 2023).

COVID-19 vaccination coverage

Vaccination against COVID-19 is currently recommended for everyone aged 18 and over, as well as individuals aged 6 months to 18 years who have certain medical conditions and/or are severely immunocompromised. Booster doses are recommended for people at higher risk of severe illness, including everyone 65 years and over, and those aged 18–64 who are severely immunocompromised. All adults aged 18–64 are eligible for a COVID-19 booster every 12 months. Adults aged 65–74 are eligible for a booster dose every 6 months, and it is recommended for adults aged 75 and above to receive a booster every 6 months (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024c). Note that previous eligibility allowed all adults to receive a booster every 6 months (or 6 months after a confirmed COVID-19 infection).

As at 12 April 2024, based on data from the AIR, among First Nations adults:

-

18,100 (3.6%) had received a COVID-19 vaccination within the previous 6 months, noting that the denominator includes those who would not have been eligible for a booster in the last 6 months due to recent infection, and people outside the groups recommended to get booster doses at that time)

-

418,800 (82.4%) had received a vaccination 6 or more months ago

-

71,500 (14.1%) were unvaccinated (Table 3.02-3).

As at 12 April 2024, 55,800 (11%) First Nations adults had received a COVID-19 vaccination booster since 1 January 2023. This was defined as having received any third or higher dose administered in sequence since 1 January 2023 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b).

Rates of recent COVID-19 vaccination for First Nations people increase with age, with rates significantly higher among First Nations adults, with the highest rates being for those aged 80 years and over. As at 12 April 2024, among First Nations people:

-

aged between 18 and 59, the vaccination rates within the past 6 months ranged from less than 1% in the 18–29 age group to 4% in the 50–59 age group. For those who had received the vaccine between 6 and 11 months ago, the rates ranged from 2% to 9% in these age groups.

For First Nations people in the older age group, for those:

-

aged 60–69, 9% had a COVID-19 vaccination in the last 6 months, and a further 14% had a vaccination between 6 and 11 months prior

-

aged 70–79, 18% had a COVID-19 vaccination in the last 6 months, and a further 19% between 6 and 11 months prior

-

aged 80 and over, 23% had a COVID-19 vaccination in the last 6 months, and a further 18% between 6 and 11 months prior (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024d).

Table 3.02-3: COVID-19 vaccination status for First Nations adults aged 18 and over, as at April 2024

|

Vaccination status |

Number |

Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Last dose <6 months ago | 18,100 | 3.6 |

| Last does more than 6 months ago | 418,800 | 82.4 |

| Unvaccinated(a) | 71,500 | 14.1 |

| Total | 508,400 | 100.0 |

(a) Unvaccinated population is based on the total number of individuals on the Australian Immunisation Register who have identified as being Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin, minus those who have a dose recorded on the Register.

Source: AIHW analysis of based on Australian Immunisation Register data as at 12 April 2024 (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b).

Influenza vaccination coverage

Annual influenza vaccination is recommended for all people aged 6 months and over, and under the NIP, is available free to the following groups:

-

all First Nations people aged 6 months and over,

-

all Australian children aged 6 months to under 5 years,

-

all Australians aged 65 and over,

-

all Australians aged 6 months and over with certain medical conditions putting them at higher risk, and

-

pregnant women (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a).

Until recently, data on influenza vaccination coverage have been based on population surveys. Since 1 March 2021, there has been mandatory reporting of influenza vaccines to the AIR. Note that these data may underestimate true coverage, due to under-reporting of adult vaccinations to the AIR, and relatively recent introduction of mandatory reporting (NCIRS 2023).

Infants and children aged under 5 have a higher risk of hospitalisation and increased risk of complications from influenza due to their still-developing immune systems (Immunisation Coalition 2024). Based on the AIR data, in 2022, among First Nations children aged from 6 months to under 5 years, 25% received an influenza vaccination (Figure 3.02.2). Immunisation coverage for First Nations children aged from 6 months to under 5 years was slightly higher in 2022 than 2021 (25% compared with 23%, respectively). However, immunisation coverage among First Nations children in this high risk age group is considered suboptimal, with three quarters unvaccinated in 2022 (NCIRS 2023).

Influenza vaccination coverage for First Nations children aged from 6 months to under 5 years was highest in the Northern Territory, at 55%; coverage rates in other jurisdictions range from 20% (in Queensland) to 38% (in the Australian Capital Territory).

Among First Nations adults aged 50–64, the proportion who received an influenza vaccination was 51%. This increased to 70% for those aged 65–74, and 72% for those aged 75 and over (Table D3.02.10) (NCIRS 2023).

Vaccination coverage rates for First Nations adults aged 65 and over were similar to the national coverage rate. Among those 65–74, the coverage rate was 69% for First Nations people and 68% for all Australians. Among those aged 75 and over, 72% of First Nations people were vaccinated, compared with 73% for all Australians (Table D3.02.10).

Figure 3.02.2: Influenza vaccination coverage among First Nations people, by age group, 2022

Source: Australian Immunisation Register, based on 2022 data as at 2 April 2023 (NCIRS 2023).

Based on self-reported data from ABS Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health surveys, between 2012–13 and 2018–19, there was an increase in the rate of vaccination against influenza among First Nations people aged 50 and over, from 57% to 68%. In remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined), the rate increased from 68% to 73% over the period, and in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas combined), the increase was from 54% to 67% (Table D3.02.8).

Influenza vaccination among First Nations primary health care organisation clients

First Nations-specific primary health care organisations are organisations that receive funding from the Department of Health and Aged Care to provide primary health care services to First Nations people. This includes Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), state and territory managed organisations, Primary Health Networks and other non-government organisations.

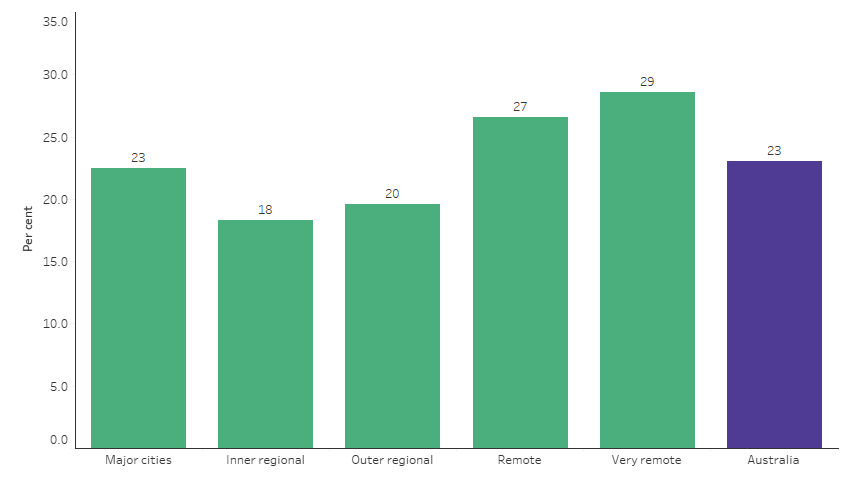

As at December 2023, 23% (81,165) of First Nations regular clients of First Nations-specific primary health care organisations who were aged 6 months or older were vaccinated against influenza. The proportion of First Nations clients vaccinated against influenza varied with remoteness areas, ranging from 18% in Inner regional areas (13,600 of 74,486 regular clients) to 29% in Very remote areas (20,611 of 72,084 regular clients) (Table D3.02.9, Figure 3.02.3).

Young children and older people infected with influenza have a higher chance of serious illness and complications, such as pneumonia. At December 2023, among First Nations regular clients aged 6 months to under 5 years, 19% of males, and 20% of females had an influenza vaccination in the previous 12 months. Among older First Nations regular clients, 35% of males and females aged 55–64 received an influenza vaccination, with this increasing to 47% of males and 48% of females aged 65 and over (AIHW 2024b).

Figure 3.02.3: Influenza vaccination coverage of First Nations regular clients of First Nations-specific primary health care organisations, by remoteness, December 2023

Source: Table D3.02.9. AIHW analysis of the National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care collection.

Pneumococcal disease vaccination coverage

Pneumococcal is a bacterial infection that can cause pneumonia, bloodstream infection and meningitis (inflammation of the membranes around the brain) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022). Vaccination is recommended for infants and children, First Nations adults aged 50 years and over, non-Indigenous adults aged 70 and over, and children, adolescents, and adults with risk conditions for pneumococcal disease.

Based on data from the AIR, in 2022, 96% of First Nations children aged 1 and 2 were vaccinated against pneumococcal disease (Table D3.02.1) (pneumococcal vaccination is included in the ‘fully immunised’ definition for children at these ages – see also Childhood immunisation coverage).

All children are eligible for 3 doses of pneumococcal vaccine. An additional dose of the pneumococcal vaccine is funded for First Nations children in four jurisdictions: Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. Coverage for the additional fourth dose by 2.5 years (30 months) of age was 80% in 2022, with the highest coverage in the Northern territory (88%) (NCIRS 2023).

Among First Nations people turning 71 years of age in 2022, 38% had been vaccinated against pneumococcal disease – an increase from 25% in 2021 (Table D3.02.10) (NCIRS 2023). Across states and territories, the vaccination rate was highest in Tasmania (53%), and lowest in Western Australia (32%).

The national vaccination coverage rate for pneumococcal disease was higher for First Nations people than all Australians turning 71 years of age in 2022 – 38% compared with 34% (Table D3.02.10). The coverage rate was higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians in all jurisdictions except Queensland, Western Australia, and South Australia (NCIRS 2023).

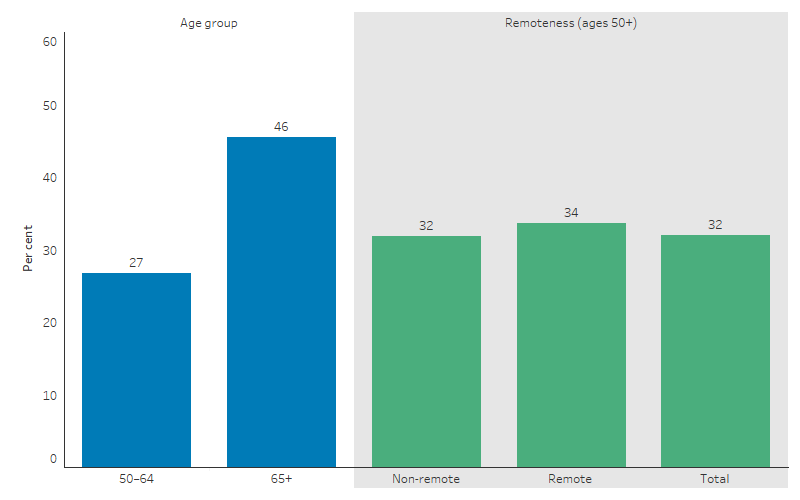

Data on immunisation of adults for pneumococcal disease is also available from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Health Survey (NATSIHS), based on self-report.

In 2018–19, 32% of First Nations people aged 50 and over had been vaccinated against pneumococcal disease in the last 5 years. The vaccination rates for pneumococcal disease for First Nations people aged 50 and over was 34% in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined) and 32% in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas combined). In 2012–13, these proportions were 35% in remote areas and 27% in non-remote areas (Table D3.02.8, Figure 3.02.4).

In 2018–19, First Nations people aged 65 and over had higher rates of immunisation against pneumococcal disease in the last 5 years (46%) compared with those aged 50–64 (27%) (Table D3.02.7).

Figure 3.02.4: First Nations people aged 50 and over who were vaccinated against pneumococcal disease in the last 5 years, by age and remoteness, 2018–19

Source: Table D3.02.7, Table D3.02.8. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

Adult vaccinations are also targeted at younger First Nations people who have various risk factors, such as chronic medical conditions. In 2018–19, 40% of First Nations people aged 15–49 were vaccinated for influenza in the previous year, and 7% had received a pneumococcal vaccination in the previous 5 years.

The 2018–19 NATSIHS found that First Nations people aged 15–49 who had diabetes/high blood sugar levels or circulatory diseases were significantly more likely to have had recent vaccinations against influenza (1.7 and 1.4 times as likely, respectively) and pneumococcal disease (2.4 and 1.8 times as likely, respectively) than First Nations people without those diseases (Table D3.02.6).

Shingles vaccination coverage among older adults

Shingles, also known as varicella-zoster, typically affects older adults and can cause severe pain. It occurs when the varicella-zoster virus, the same virus that causes chickenpox, becomes reactivated in the body. Following the initial chickenpox infection, the virus remains dormant in nerve cells. It can later reactivate as shingles, affecting sensory nerves and typically presenting as a painful rash accompanied by symptoms like headache, fatigue, and fever. The rash progresses into blisters and enters the most painful stage of infection. In cases of chronic shingles, the pain can persist for over four weeks (Healthdirect 2024).

Vaccination is crucial for reducing the risk of shingles, post-herpetic neuralgia, intermittent or continuous nerve pain in an area of your skin previously affected by shingles, and its associated complications. Data in this section are for 2022 – at that time, free vaccination was available through the NIP to people aged 70 and over. From 1 November 2023, eligibility expanded, with vaccination now available for free for all adults aged 65 and over, First Nations people aged 50 and over, and immunocompromised adults with haemopoietic stem cell transplant, solid organ transplant, haematological malignancy and advanced or untreated HIV.

Among First Nations people turning 71 years of age in 2022, 37% were vaccinated for shingles, compared with 41% for all Australians. Coverage varied across states and territories, ranging from 16% for First Nations people in the Northern Territory to 50% for First Nations people in the Australian Capital Territory (Figure 3.02.5) (NCIRS 2023).

Figure 3.02.5: First Nations people turning 71 years of age in 2022 who had been vaccinated for shingles, by state and territory

Note: People were considered vaccinated if they had received one dose of Zostavax® or two doses of Shingrix®.

Source: Annual Immunisation coverage report 2022 (Figure 24), based on AIR data as at 2 April 2023 (NCIRS 2023).

Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) vaccination

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) can cause a range of respiratory conditions, from mild cold-like symptoms to severe illnesses such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia (NCIRS 2024). The risk of severe RSV disease is higher among infants, young children, adults with medical conditions, and older adults.

Data on the RSV disease burden for First Nations people is limited. First Nations infants and young children in this age group are hospitalised with RSV at twice the rate of the rest of the population (NCIRS 2024).

In Australia, RSV vaccines are not currently funded under the NIP. Adults aged 60 and over are able to access an RSV vaccine via private purchase. In 2024, infant vaccination for RSV is being offered in Western Australia, Queensland and New South Wales, with a particular focus on First Nations infants.

Research and evaluation findings

Recent research illustrates the importance of vaccinations for First Nations people. The results point to the ongoing requirement for improvements in the rate of timely vaccinations for First Nations children, and the importance of vaccination in pregnancy and for older First Nations people with increased risk of severe illness. Health care providers play a vital role in encouraging vaccinations for First Nations adults.

A cross-sectional analysis of AIR data (2008–2016) found that a program aimed at improving the rates of vaccinations contributed to the improved vaccination rates for First Nations Australian children in New South Wales (Hendry et al. 2018). The study assessed both the vaccination rates and the timeliness of receipt of vaccinations in children. Vaccinations were compared across First Nations and non-Indigenous children in New South Wales and the rest of Australia, between 2008 and 2016. A comparison of vaccination coverage before and after the introduction of the Aboriginal Immunisation Health care Worker (AIHCW) Program in New South Wales in 2012 showed a significant increase in rates of First Nations and non-Indigenous children fully vaccinated at 9, 15 and 51 months of age. The increases in the vaccination rate were prominent in New South Wales after the introduction of the AIHCW Program compared with the rest of Australia.

A study examined the impact of introducing Aboriginal Health Workers to implement an immunisation pre-call service and found a marked increase in immunisation coverage for First Nations children at 12 months of age, where the gap in immunisation coverage between First Nations and non-Indigenous children significantly narrowed from 8.4% to 1.4%. This intervention involved a pre-call strategy where Aboriginal Immunisation Officers actively contacted families of First Nations infants before their scheduled immunisation dates, as a measure to promote timely vaccination and enhance overall coverage rates. The study included all First Nations children born in New South Wales during the study period, noting that by the end, 6,222 out of 7,086 First Nations children aged 12–15 months in the Hunter New England Local Health District (HNELHD) of New South Wales were fully immunised from March 2010 to September 2014. By the conclusion of the study period, the immunisation coverage for First Nations infants in HNELHD not only met but also exceeded that of non-Indigenous infants by 0.8%. The success of the strategy was largely attributed to the crucial role played by the Aboriginal Immunisation Officers, whose engagement with the families ensured better access to timely immunisation (Cashman et al. 2016).

Various other studies aimed at improving immunisation rates and timeliness among First Nations children through communication methods have also yielded insightful results. A retrospective cohort analysis at the Aboriginal Medical Service Western Sydney demonstrated that personalised calendars significantly reduced the average delay in childhood immunisations to 0.6 months compared with 3.3 months for those without calendars, with 80% of doses being on time versus 57% in the control group (who did not receive a calendar) (Abbott et al. 2013). In Victoria, a randomised controlled trial showed that personalised letters to parents increased influenza vaccination rates among First Nations children by a third, to 5.9% which was significantly higher compared with the control group rate of 4.4% (although this was higher than previous years). Whereas pamphlets were found to be ineffective, with a rate of 4.5%. These findings collectively highlight that personalised and culturally appropriate communication methods, such as personalised calendars, SMS reminders and letters are effective in improving immunisation rates and timeliness, whereas less personalised methods like pamphlets are less impactful (Borg et al. 2018). Similarly, a quasi-experimental study in Central Queensland found that SMS reminders sent to parents five days before scheduled immunisation milestones (6 weeks, 4 months, 6 months, 12 months and 18 months) significantly improved rates of ‘on-time’ vaccination, with absolute risk differences between the intervention group and control group ranging from 4.7% to 12.9% at various milestones. Improvement was seen at all milestones except 12 months. These results are comparable to increases in the proportion of child vaccinations seen in international research publications. The study also found that coverage rates were increasing from 2013 to 2017, even before the Australian Government’s 'No Jab, No Pay' initiative was introduced in 2016, demonstrating the community's proactive commitment to child health and wellbeing (Manderson et al. 2023).

A retrospective population-based cohort analysis estimated the effectiveness of the NIP on the uptake of all 3 doses of pneumococcal vaccines before the age of 1 by comparing the vaccine coverage among 1.3 million children born between July 2001 and December 2012, before and after the universal program period, in New South Wales and Western Australia. The overall 3 dose vaccine coverage for First Nations children increased from 36.6% to 82.9%. For First Nations children with medically at-risk conditions, the rates increased from 38.5% to 80.7%. However, coverage for additional recommended booster doses, such as having the 4th dose of the pneumococcal vaccines, remained low. The findings highlight the need for improved implementation strategies to strengthen the routine vaccination schedule and ensure adequate coverage for high-risk groups (Kabir et al. 2021).

Maternal immunisation has the potential to reduce the burden of infectious diseases in both pregnant women and infants. Marshall et al. (2016) assessed maternal immunisation internationally and noted the role of cultural factors in vaccination programs in order to maximise the uptake of new vaccines for pregnant women (Marshall et al. 2016). They also emphasised the importance of pregnant women having confidence in immunisation providers.

The burden of acute lower respiratory infection (ALRI) in First Nations children of Australia's Northern Territory is among the highest globally. A population-based cohort study examined the effectiveness of maternal pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) in preventing ALRI hospitalisations in First Nations infants residing in the Northern Territory from 2006 to 2015. A 30% reduction in bacterial-coded pneumonia hospitalisations (one of the types of ALRI measured) in the Northern Territory during the era of 13-valent PCV immunisation during 2011–15, supports its ongoing use in the region. Despite the reduction, one in five First Nations infants born in the region continue to be hospitalised with an ALRI in their first year of life (Binks et al. 2020).

A cross-sectional study nested within a randomised controlled trial (RCT) recommended prioritising activities to improve and monitor maternal influenza vaccination coverage for First Nations women (Moberley et al. 2016). First Nations pregnant women who participated in a vaccination trial before and during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic were studied to determine vaccination coverage. Key findings included:

-

Vaccine coverage over the study period increased from 2.2% in the period 2006 to 2009 to 41% in the period 2009 to 2010.

-

Increased maternal influenza vaccination coverage signified greater readiness of First Nations women to be vaccinated.

A survey of First Nations mothers who had recently given birth in Central Australia found:

-

Awareness and uptake by pregnant mothers of influenza vaccination was greater than for pertussis (whooping cough).

-

Vaccination self-reporting underestimated vaccine coverage.

-

There was a good understanding of public health messages of the benefits of maternal vaccination.

-

Lack of health care provider recommendations is the main reason for non-vaccination (Krishnaswamy et al. 2018).

A study in New South Wales found barriers to influenza vaccination among First Nations adults included health system barriers and misconceptions among First Nations people about the vaccine. Poor quality Indigenous status identification in primary health care settings and insufficient recommendations and reminders from health care providers may be contributing to a lack of awareness and lower uptake of the vaccine. There were also misconceptions among First Nations people over vaccine effectiveness, safety, and the severity of influenza. Younger adults and more highly educated adults were less likely to get vaccinated (Menzies et al. 2020).

Data from the national key performance indicators for Indigenous-specific primary health care show that influenza vaccination coverage for adults aged over 50 is improving and stronger improvements are being seen in Major cities, albeit from a lower base (AIHW 2024). This highlights the value of having good quality service-level data for driving improvements, and that ACCHSs are demonstrating to mainstream services that progress is possible even in difficult to reach non-remote environments. Further research is needed to unpack successful strategies to improve vaccination that can be implemented, in particular in mainstream primary health care.

High rates of the first dose of the HPV vaccination among First Nations adolescents is being seen in school-based programs, but strategies are needed to improve the completion rates for First Nations people (Brotherton et al. 2019).The ‘Communicable Diseases Intelligence - Vaccine Preventable Diseases and Vaccination Coverage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Australia, 2016–2019' report analyses health database records to assess vaccination outcomes and the prevalence of vaccine-preventable diseases among First Nations peoples. It aims to guide policy development and improve service delivery by presenting a detailed overview of immunisation trends from 2016 to 2019. The report identifies key factors contributing to the improvement in vaccination coverage during this period, including significant updates to the NIP. These updates encompass the introduction of new immunisation incentives, such as ‘No Jab, No Pay’, and revisions to the methods used to calculate coverage. These enhancements led to an increase in vaccination rates, with 92.9% of First Nations children vaccinated by 12 months of age, 90.0% by 24 months, and 96.9% by 60 months. Additionally, the report highlights a substantial reduction in diseases such as Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib), a bacterium that causes a life-threatening infection that can lead to serious illness, especially in children. Although Hib infection incidence decreased by more than 99% since the introduction of the vaccine in 1993, the rates of Hib infection for First Nations children are still about 12 times as high as those among non-Indigenous children. The successful management of hepatitis A through targeted immunisation programs has resulted in notification rates for First Nations people being consistently lower than those for other Australians, with no notifications or hospitalisations reported in First Nations children under 5 years during the review period (Jackson et al. 2023).

The 2024 Grattan Institute report highlighted that high-risk First Nations adults had a COVID-19 vaccination rate that was about one-third less than the average high-risk individual. As defined by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI), a high-risk individual includes those aged 65 or older or those with medical comorbidities that elevate their risk for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Geographic disparities significantly influence vaccination rates, with those residing in Remote or Very remote areas being about 35% less likely to receive vaccinations compared with those in Inner regional areas. Additionally, socioeconomic conditions influence vaccine uptake; the least disadvantaged adults are 62% more likely to be up-to-date with their COVID-19 vaccinations compared with their most disadvantaged counterparts. The intersectionality of risks, such as low income and remote living conditions, compound access barriers, progressively reducing the likelihood of vaccination with each added risk factor. This reduced vaccination rate among First Nations people correlates with higher COVID-19 death rates (Breadon & Burfurd 2024).

There were clear gaps in uptake of COVID-19 vaccination. Analysis of first-dose vaccination rates by mid-January 2022 showed that First Nations people were significantly and substantially less likely to be vaccinated (Biddle et al. 2022). Those living in Very remote areas were about 35 per cent less likely to have had a recent COVID-19 vaccine as those in Inner regional areas (Breadon & Stobart 2023).

COVID-19 antiviral treatment reduces the severity of illness, minimising the risk of hospitalisation and death (Bernal et al. 2022; Pfizer 2021). High-risk people living in remote areas are 80 per cent less likely to get antiviral treatment than people living in Major cities, and First Nations people are 45 per cent less likely to get treatment than non-Indigenous Australians (Breadon & Stobart 2023). A qualitative study involving 35 First Nations people aged 15–80 living in Western Sydney found that First Nations people preferred to access COVID-19 vaccination through their local Aboriginal medical service or a GP with whom they had an existing and trusting relationship. Reasons why some participants were hesitant about being vaccinated included: fear of vaccine side effects; negative stories on social media; and distrust in Australian governments and medical institutions (Graham et al. 2022; Simon et al. 2022).

A study analysed the spatial variation of COVID-19 vaccination for First Nations people across locations in Australia. Using Local Government Areas (LGAs) data from November 2021 to June 2022, findings indicated a considerable range in vaccination coverage, from 62.9% to 97.5% across LGAs. Rural areas exhibited lower vaccination rates compared with urban counterparts, likely due to challenges in health care access and vaccine distribution logistics. Additionally, lower socioeconomic status was linked to lower vaccination rates. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) were pivotal in promoting COVID-19 vaccination uptake and contributing to the broader public health response to COVID-19 in Australia. These findings highlight how geography significantly influences the accessibility and success of COVID-19 vaccination among First Nations communities, with high coverage rates underscoring community strength and resilience (Soares et al. 2024).

Implications

Achieving good immunisation coverage reflects the strength and effectiveness of primary health care and demonstrates the benefits of large-scale vaccination programs that have little or no cost to eligible participants. The high rates of vaccination for First Nations children is a significant achievement. However, there are still improvements that can be made to increase the vaccination rates in First Nations children, adolescents, and adults. Targeted communication strategies to overcome barriers to vaccination and misconceptions about vaccination could be beneficial. Activities to encourage uptake among First Nations audiences for influenza and routine childhood vaccinations were undertaken in 2022–23.

The Australian Government recognises that immunisation is highly effective in reducing illness and death caused by communicable diseases – diseases that can spread from person to person. The following initiatives aim to reduce the transmission of diseases.

The National Immunisation Program (NIP) is a collaborative initiative in which the Australian Government is responsible for managing national immunisation policy and vaccine procurement, while state and territory governments are tasked with coordinating immunisation service delivery and managing vaccine distribution. The NIP provides free childhood vaccines to eligible Australians and includes specific supplementary vaccines for First Nations people, such as:

- pneumococcal vaccine and hepatitis A vaccine for children in high-risk areas

- pneumococcal vaccine for persons aged 15–49 who are medically at risk, and adults aged 50 years and over

- seasonal influenza vaccines for all Indigenous Australians aged 6 months and over.

Through the National Immunisation Strategy for Australia 2019-24, the Australian and state and territory governments have committed to work towards achieving 95% immunisation coverage for First Nations children aged 1, 2 and 5 years. This is supported by performance benchmarks outlined in the Essential Vaccines Schedule (EVS) of the Federation Funding Agreement – Health (previously the National Partnership on Essential Vaccines, or NPEV). The EVS outlines six key outcomes designed to reduce the incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases across the Australian population and enhance vaccine management and reporting. This includes a specific outcome to minimise the incidence of vaccine preventable diseases in First Nations people for diseases with vaccines listed under the NIP. For the fifth year of the agreement, covering the assessment period 1 April 2021 to 31 March 2022, all states and territories successfully met the performance benchmark of an increase in the vaccination coverage rate for First Nations people in at least two of the following three age cohorts: 12 to under 15 months; 24 to under 7 months; and 60 to under 63 months, relative to the baseline (AIHW 2023).

The National Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccination Program began in 2007 for females and was extended to males in February 2013. It is delivered through an ongoing, school-based program to students aged 12–13. Communication activities to support the NIP and the HPV Vaccination Program include specific components for First Nations people, including tailored resources and social media about the vaccines and eligibility.

The National Preventive Health Strategy 2021-2030 aims to improve health and reduce disparities for First Nations communities, addressing the disproportionate burden of chronic diseases and the social determinants affecting these populations. Emphasising culturally sensitive health initiatives, the strategy targets the root causes of health disparities, such as intergenerational trauma, and integrates traditional knowledge and practices in health interventions. A key focus is on enhancing immunisation coverage, with targets to achieve at least 95% coverage for First Nations children aged 1 and 2 years by 2030 and maintaining this rate for children aged 5 years. This approach ensures that immunisation programs are culturally safe and accessible across all life stages, addressing the higher burden of vaccine-preventable diseases in these communities.

The Health Plan is guided by the National Agreement in aiming to transform government engagement with First Nations people and monitor key health targets. The Health Plan envisions long, healthy lives for First Nations people, supported by culturally safe, equitable, and prevention-focused services. It emphasises a holistic approach to prevention, aligning with the National Preventive Health Strategy to maintain and promote wellbeing. Priority 4 highlights health promotion, recognising culture as a protective factor, and includes a focus on immunisation to protect against preventable conditions. Objective 4.4 ensures culturally safe and responsive immunisation programs, prioritising access to vaccines and addressing the disproportionate impact of pandemics on these communities.

The Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) supports first-time First Nations mothers through a series of regular home visits from pregnancy until the child reaches 2 years old. These visits are conducted by specially trained Nurse Home Visitors (NHV) and Family Partnership Workers (FPW), who work together to provide information and education, which includes a focus on immunisation up to a child's second birthday and promotes healthy pregnancies and confident parenting. By focusing on empowering the mothers within the context of their local First Nations communities, the ANFPP not only ensures cultural safety but also aims to secure a healthy start and future success for both the mothers and their children.

Health care providers play a central and vital role in encouraging vaccination. Research is needed into effective strategies for encouraging vaccination among First Nations clients of mainstream primary health care. There is also a need for better identification of First Nations clients of mainstream primary health care in order for services to make vaccinations more available to First Nations adults. Data collection for continuous quality improvement can be used to drive or at least demonstrate improvements.

The health system should be working to minimise the impact of any future pandemic on the most disadvantaged. Australia’s vaccination system needs to be strengthened to ensure that everyone can get rapid access to vaccines that reduce the risks of infection and illness before being infected, and any treatments that reduce those risks after being infected. Prevention programs need to consider existing inequalities and support disadvantaged communities (Breadon & Stobart 2023).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

Abbott P, Menzies R, Davison J, Moore L & Wang H 2013. Improving immunisation timeliness in Aboriginal children through personalised calendars. BMC Public Health 13:598.

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2023. Essential vaccines: performance report 2021-22, catalogue number HPF 69. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

AIHW 2024. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: results from the OSR and nKPI collections. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed June 2024.

-

Bernal AJ, Gomes da Silva MM, Musungaie DB, Kovalchuk E, Gonzalez A, Delos Reyes V et al. 2022. Molnupiravir for oral treatment of Covid-19 in nonhospitalized patients. New England Journal of Medicine 386:509-20.

-

Biddle N, Welsh J, Butterworth P, Edwards B & Korda R 2022. Socioeconomic determinants of vaccine uptake: July 2021 to January 2022. ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods and National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health: Canberra, Australia.

-

Binks MJ, Beissbarth J, Oguoma VM, Pizzutto SJ, Leach AJ, Smith-Vaughan HC et al. 2020. Acute lower respiratory infections in Indigenous infants in Australia's Northern Territory across three eras of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine use (2006-15): a population-based cohort study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 4:425-34.

-

Borg K, Sutton K, Beasley M, Tull F, Faulkner N, Halliday J et al. 2018. Communication-based interventions for increasing influenza vaccination rates among Aboriginal children: A randomised controlled trial. Vaccine 36:6790-5.

-

Breadon P & Burfurd I 2024. A fair shot: How to close the vaccination gap. Gratton Institute.

-

Breadon P & Stobart A 2023. How to prepare for the next pandemic: Submission to the federal government’s COVID Response Inquiry. Grattan Institute.

-

Brotherton JM, Winch KL, Chappell G, Banks C, Meijer D, Ennis S et al. 2019. HPV vaccination coverage and course completion rates for Indigenous Australian adolescents, 2015. Medical Journal of Australia 211:31-6.

-

Burgess M 2003. Immunisation: a public health success. New South Wales Public Health Bulletin 14:1-5.

-

Cashman PM, Allan NA, Clark KK, Butler MT, Massey PD & Durrheim DN 2016. Closing the gap in Australian Aboriginal infant immunisation rates -- the development and review of a pre-call strategy. BMC Public Health 16:514-.

-

Crooks K, Casey D & Ward JS 2020. First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. Med J Aust 213:151-2.e1.

-

Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Australian Government of Department of Health, Canberra.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2022. Pneumococcal vaccine. Viewed May 2024.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2023. HPV (human papillomavirus) vaccine. Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Viewed June 2023.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a. 2024 Influenza vaccination – Program advice for vaccination providers. Viewed May 2024.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b. COVID-19 vaccination – vaccination data – 12 April 2024. Canberra. Viewed May 2024.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024c. COVID-19 vaccine advice and recommendations for 2024. Viewed July 2024.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024d. First Nations COVID-19 vaccination coverage – National data – 12 April 2024. Department of Health and Aged Care,. Viewed May 2024.

-

Dudgeon P, Collova JR, Derry K & Sutherland S 2023. Lessons Learned during a Rapidly Evolving COVID-19 Pandemic: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander-Led Mental Health and Wellbeing Responses Are Key. Vol. 20.

-

Graham S, Blaxland M, Bolt R, Beadman M, Gardner K, Martin K et al. 2022. Aboriginal peoples' perspectives about COVID-19 vaccines and motivations to seek vaccination: a qualitative study. BMJ Glob Health 7.

-

Healthdirect 2024. Shingles. Viewed May 2024.

-

Hendry AJ, Beard FH, Dey A, Meijer D, Campbell-Lloyd S, Clark KK et al. 2018. Closing the vaccination coverage gap in New South Wales: the Aboriginal Immunisation Healthcare Worker Program. The Medical journal of Australia 209:24-8.

-

Immunisation Coalition 2024. Enhancing Influenza Vaccination Uptake in Children Under 5 years in Australia in 2024. Viewed May 2024.

-

Jackson J, Sonneveld N, Rashid H, Karpish L, Wallace S, Whop L et al. 2023. Vaccine Preventable Diseases and Vaccination Coverage in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, Australia, 2016-2019. Commun Dis Intell (2018) 47.

-

Kabir A, Newall AT, Randall D, Menzies R, Sheridan S, Jayasinghe S et al. 2021. Estimating pneumococcal vaccine coverage among Australian Indigenous children and children with medically at-risk conditions using record linkage. Vaccine 39:1727-35.

-

Krishnaswamy S, Thalpawila S, Halliday M, Wallace EM, Buttery J & Giles M 2018. Uptake of maternal vaccinations by Indigenous women in Central Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 42:321.

-

Manderson J, Smoll N, Krenske D, Nedwich L, Harbin L, Charles M et al. 2023. Communicable Diseases Intelligence. Canberra: Departent of Health and Aged Care,.

-

Marshall H, McMillan M, Andrews RM, Macartney K & Edwards K 2016. Vaccines in pregnancy: The dual benefit for pregnant women and infants. Hum Vaccin Immunother 12:848-56.

-

Menzies R, Aqel J, Abdi I, Joseph T, Seale H & Nathan SA 2020. Why is influenza vaccine uptake so low among Aboriginal adults? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 44:279-83.

-

Menzies R & Singleton RJ 2009. Vaccine preventable diseases and vaccination policy for indigenous populations. Pediatric Clinics of North America 56:1263-83.

-

Moberley SA, Lawrence J, Johnston V & Andrews RM 2016. Influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant Indigenous women in the Northern Territory of Australia. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep 40:E340-E6.

-

NCIRS (National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance) 2023. Annual Immunisation Coverage Report 2022. The National Centre for Immunisation Research and Surveillance.

-

NCIRS 2024. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) immunisation. Viewed June 2024.

-

Overton K, Webby R, Markey P & Krause V 2016. Influenza and pertussis vaccination coverage in pregnant women in the Northern Territory in 2015 – new recommendations to be assessed. Vol. 23 (ed., Health Do). Centre for Disease Control, 1-8.

-

Pfizer 2021. Pfizer announces additional phase 2/3 study results confirming robust efficacy of novel COVID-19 oral antiviral treatment candidate in reducing risk of hospitalization or death. Pfizer.

-

Simon G, Megan B, Reuben B, Mitchell B, Kristy G, Kacey M et al. 2022. Aboriginal peoples’ perspectives about COVID-19 vaccines and motivations to seek vaccination: a qualitative study. BMJ Global Health 7:e008815.

-

Soares GH, Hedges J, Poirier B, Sethi S & Jamieson L 2024. Deadly places: The role of geography in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander COVID-19 vaccination. Aust N Z J Public Health 48:100130.

-

Yashadhana A, Pollard-Wharton N, Zwi AB & Biles B 2020. Indigenous Australians at increased risk of COVID-19 due to existing health and socioeconomic inequities. Lancet Reg Health West Pac 1:100007-.