Key messages

- Potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) are hospitalisations considered to have been avoidable if timely and adequate non-hospital care had been provided, either to prevent the condition occurring, or to prevent the hospitalisation for the condition. There were 91,703 PPH for Aboriginal for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people in the 2-year period from July 2019 to June 2021, corresponding to a rate of 53 PPH per 1,000 population.

- PPH fall into 3 broad categories: vaccine-preventable conditions, acute conditions, and chronic conditions. Between July 2019 and June 2021, First Nations people were hospitalised for potentially preventable acute conditions at a rate of 27 PPH per 1,000 population, chronic conditions at a rate of 22 PPH per 1,000 population, and vaccine-preventable conditions at a rate of 5.9 PPH per 1,000 population.

- Between July 2019 and June 2021, for First Nations people, the leading causes of hospitalisations due to vaccine-preventable conditions were chronic hepatitis B (65%) and influenza (19%). For PPH due to acute conditions, cellulitis (22%) in conjunction with dental conditions and urinary tract infections (both 18%) were the leading causes. For PPH due to chronic conditions, COPD (28%) and diabetes complications (24%) were the leading causes.

- First Nations people were hospitalised for potentially preventable conditions at 3 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians between July 2019 and June 2021 (based on age-standardised rates).

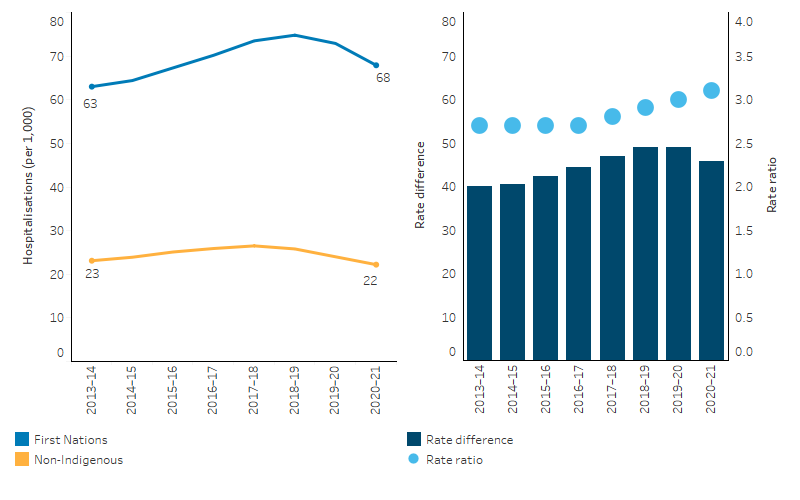

- The age-standardised rate of PPH for First Nations people increased between 2013–14 and 2018–19 (from 63 to 75 PPH per 1,000 population), before decreasing to 68 PPH per 1,000 population in 2020–21. This was mainly due to a decrease in vaccine-preventable hospitalisations. The decrease coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic, and public health measures put in place to control the pandemic (such as physical distancing, mask-wearing and handwashing) would have also affected the spread of other infectious diseases.

- Overall, between 2013–14 and 2020–21, the gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians increased, from a rate difference of 40 PPH per 1,000 population (in 2013–14) to 46 PPH per 1,000 population (in 2020–21).

- A historical cohort study of First Nations residents living in remote communities in the Northern Territory from 2002 to 2011 found that those who utilised primary health care at medium/high levels were less likely to be admitted to hospital than those in the low utilisation group, and that higher levels of primary care utilisation for renal disease reduced avoidable hospitalisations by 82%–85%, and 63%–78% for ischaemic (coronary) heart disease.

- The cohort study also showed that primary health care in remote First Nations communities was shown to be associated with cost-savings to public hospitals and health benefits to individual patients. Investing $1 in primary care in remote First Nations communities could save $3.95–$11.75 in hospital costs, in addition to health benefits for individual patients.

- Comprehensive, accessible and well-integrated care is needed, particularly in managing chronic conditions, in order to prevent hospitalisations and death from avoidable causes. Ensuring services, particularly Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs), are accessible and appropriate throughout Australia is therefore important to drive reductions in PPH and avoidable deaths.

Why is it important?

An analysis of the conditions for which people are admitted to hospital revealed that, in many cases, the hospital admission could have been prevented through timely and effective care outside of hospital (Li et al. 2009). Hospitalisations for conditions that could potentially have been prevented through provision of appropriate preventative health interventions and early disease management in primary care and community-based care settings are referred to as potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) (AIHW 2022a). This is a key measure of the performance of the health system. In particular, it serves as a proxy measure of access to timely, effective and appropriate primary and community-based care (AIHW 2020). The term ‘PPH’ does not mean that the patient did not require hospitalisation at the time of the admission, but that hospitalisation could potentially have been prevented with effective management in primary or community health care settings (AIHW 2019a).

PPH fall into 3 broad categories:

- vaccine-preventable conditions – including, influenza, tetanus, whooping cough, chicken pox, and measles

- acute conditions – including cellulitis (skin infections), urinary tract infections, convulsions/epilepsy, dental conditions, ear nose and throat infections

- chronic conditions – including many forms of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes complications, asthma, iron deficiency and hypertension.

Systematic differences in hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people and non-Indigenous Australians can indicate gaps in the provision of population health interventions (such as immunisation), primary care services (such as early interventions to detect and treat chronic disease), and continuing care support (such as care planning for people with chronic illnesses, e.g., congestive heart failure). However, higher hospitalisation rates can also reflect appropriate referral mechanisms and access to hospital care. Among First Nations people, there is also a higher prevalence of the underlying diseases, indicating deficiencies in access to primary health care and prevention/health promotion services. First Nations people are also more likely to live in remote areas where non-hospital alternatives are limited (Gibson & Segal 2009; Li et al. 2009).

The PPH rates for First Nations people need to be understood in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and cultures. This history and the ongoing affects of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism has fundamentally affected the determinants of health and wellbeing. In light of this context, it is important to recognise the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) sector which plays a significant role in providing comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people (Panaretto et al. 2014).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations people’s health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Early access to responsive primary care, and addressing barriers to accessing care, are identified by the Health Plan as key to addressing high hospitalisation rates for First Nations people. The Health Plan includes among its priorities a focus on prevention and early intervention; having a strong, sustainable and equipped ACCHS sector; and improving the health system such as through eliminating racism and improving cultural safety among mainstream health settings (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

In the period July 2019 to June 2021, there were 91,703 potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) for First Nations people, corresponding to a rate of 53 PPH per 1,000 population (Table D3.07.3).

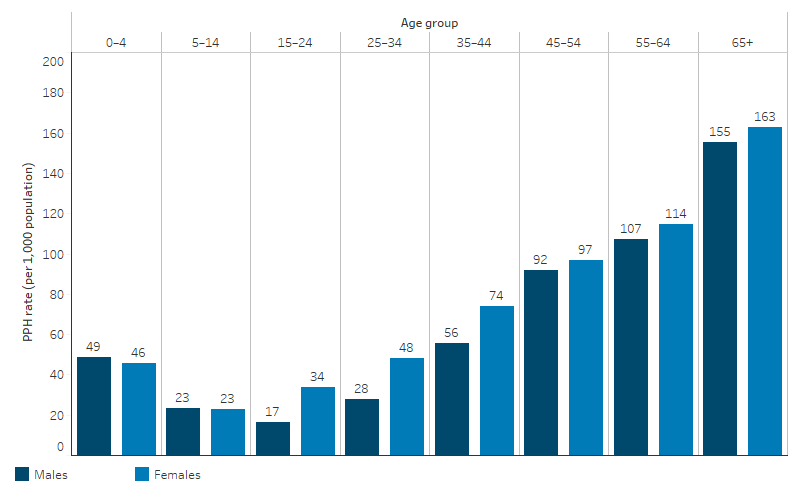

PPH rates were generally higher in older age groups. For First Nations people, the PPH rate was lowest for children aged 5–14 (23 PPH per 1,000 population). Among First Nations people aged over 5, the rate increased with successive age groups, with the highest rate of 163 PPH per 1,000 population for those aged 65 and over (Table D3.07.1).

Rates of PPH were higher for First Nations females than First Nations males (59 compared with 47 PPH per 1,000 population). This was true across all age groups except for those aged 5–14 (where rates for both were around 23 PPH per 1,000 population) and those aged under 5 (where the rate for males was higher than for females – 49 compared with 46 per 1,000 population).

The largest difference in rates by sex for First Nations people were for the age groups 15–24, 25–34 and 35–44, where the rate for females was between 17 and 20 PPH per 1,000 population higher than for males, compared with a difference of 8 PPH per 1,000 population or less in other age groups (Table D3.07.1, Figure 3.07.1).

Figure 3.07.1: Potentially preventable hospitalisation rate for First Nations people, by sex and age group, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.1. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019) for calculation of rates.

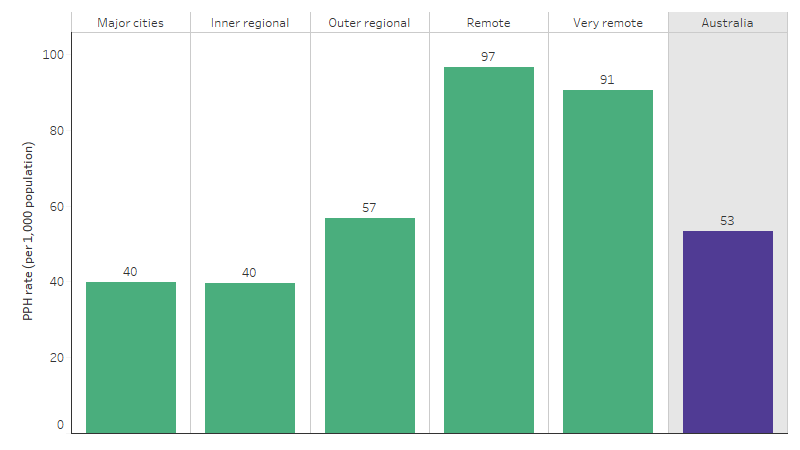

At a national level, the rate of PPH for First Nations people was higher for those living in remote than non-remote areas. The rate among First Nations people was highest for those living in Remote areas (97 PPH per 1,000 population), followed by Very remote areas (91 PPH per 1,000 population). The rate was lowest for those in Major cities and Inner regional areas (both 40 PPH per 1,000 population), followed by Outer regional areas (57 per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.3, Figure 3.07.2).

Figure 3.07.2: Potentially preventable hospitalisation rate for First Nations people, by remoteness, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.3. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019) for calculation of rates

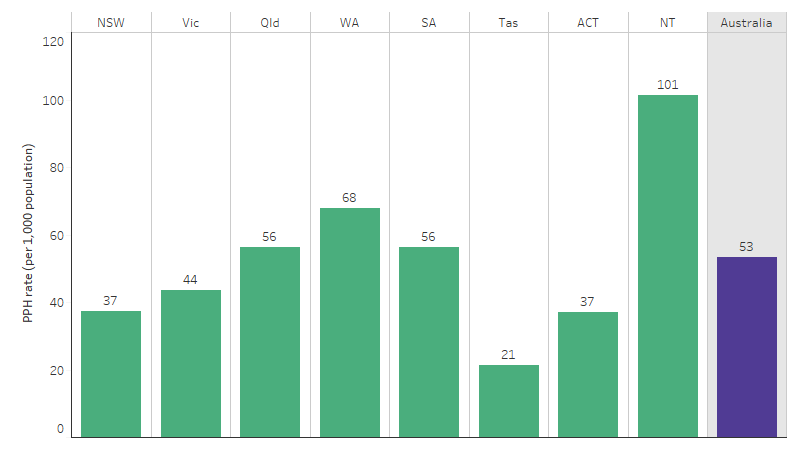

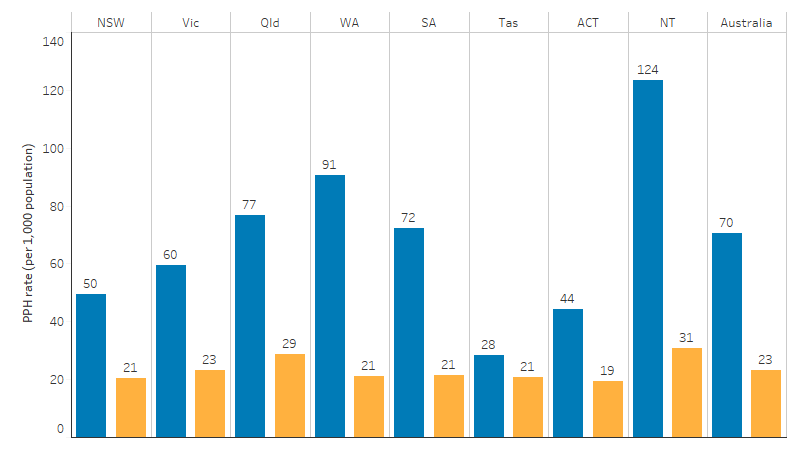

Across states and territories, PPH rates were lowest for First Nations people living in Tasmania (21 PPH per 1,000 population) and highest for those living in the Northern Territory (101 PPH per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.2, Figure 3.07.3).

Figure 3.07.3: Potentially preventable hospitalisation rate for First Nations people, by jurisdiction, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.2 and D3.07.3. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019) for calculation of rates.

Leading causes of potentially preventable hospitalisations

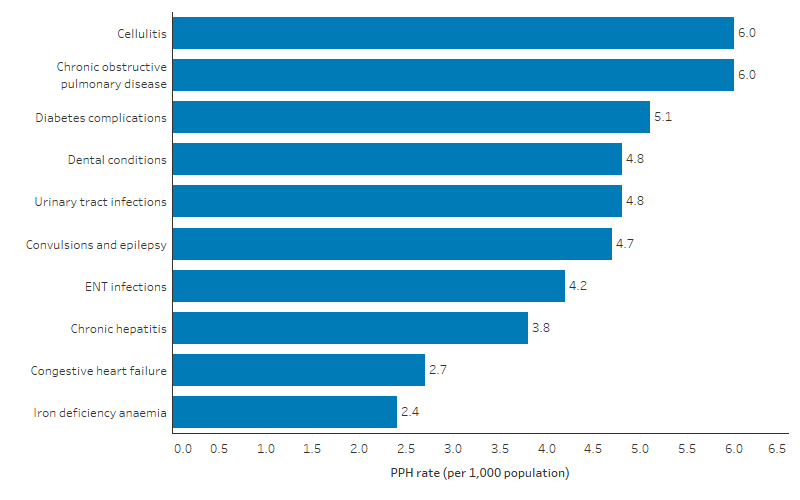

Between July 2019 and June 2021, of 91,703 total selected PPH among First Nations people, the 5 leading causes were:

- cellulitis, which accounted for 11.3% (10,324 PPH, or 6.0 PPH per 1,000 population)

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), which accounted for 11.2% (10,276 PPH or 6.0 PPH per 1,000 population)

- diabetes conditions, which accounted for 9.6% (8,829 PPH or 5.1 PPH per 1,000 population)

- dental complications, which accounted for 9.1% (8,345 PPH or 4.8 PPH per 1,000 population)

- urinary tract infections (including pyelonephritis), which accounted for 9.0% (8,272 PPH or 4.8 PPH per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.5, Figure 3.07.4).

Figure 3.07.4: Potentially preventable hospitalisation rate for First Nations people, top 10 leading causes, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.5. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019) for calculation of rates.

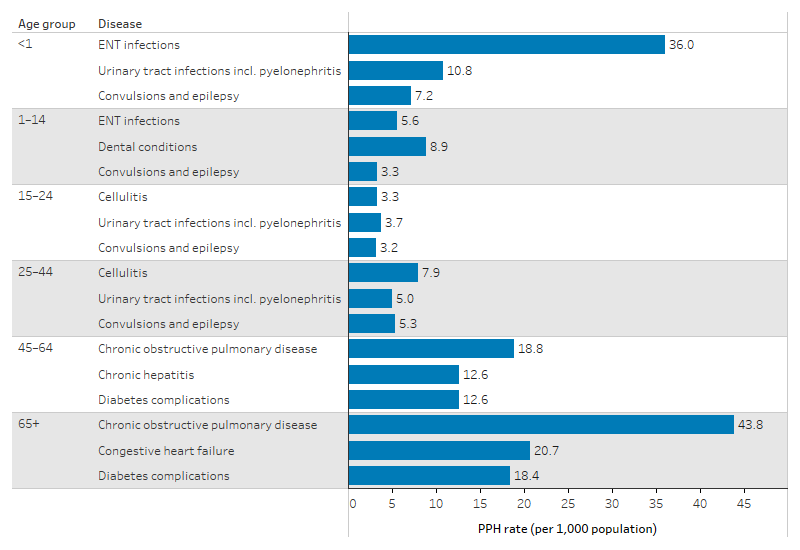

The leading causes of PPH among First Nations people by age group were:

- ear, nose and throat infections for infants aged under 1 (36.0 PPH per 1,000 population)

- dental conditions for children aged 1–14 (8.9 PPH per 1,000 population)

- urinary tract infections for those aged 15–24 (3.7 PPH per 1,000 population)

- cellulitis for those aged 25–44 (7.9 PPH per 1,000 population)

- COPD for those aged 45 and over (18.8 PPH per 1,000 population for those aged 45–64 and 43.8 PPH per 1,000 population for those aged 65 and over) (Table D3.07.6, Figure 3.07.5).

Figure 3.07.5: Rates of the top 3 potentially preventable hospitalisations among First Nations people, by age group, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.6. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019) for calculation of rates.

When grouping PPH conditions among First Nations people into acute, chronic and vaccine-preventable conditions:

- acute conditions accounted for 50% (46,153) of all PPH (26.8 PPH per 1,000 population)

- chronic conditions accounted for 41% (37,195) of all PPH (21.6 PPH per 1,000 population)

- vaccine-preventable conditions accounted for 11% (10,097) of all PPH (5.9 PPH per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.12).

Note that the sum of the categories exceeds the total, as more than one potentially preventable condition can be diagnosed for each hospitalisation.

For First Nations people, the leading causes of PPH due to acute conditions were:

- cellulitis, a skin infection usually caused by bacteria, accounted for 22% of all PPH due to acute conditions (6.0 PPH per 1,000 population)

- dental conditions and urinary tract infections, both accounted for 18% of all PPH due to acute conditions (4.8 PPH per 1,000 population).

The leading causes of PPH due to chronic conditions among First Nations people were:

- COPD, accounted for 28% of PPH due to chronic conditions (6.0 PPH per 1,000 population)

- diabetes complications, accounted for 24% of PPH due to chronic conditions (5.1 PPH per 1,000 population)

- congestive heart failure, accounted for 12% of PPH due to chronic conditions (2.7 PPH per 1,000 population).

The leading causes of hospitalisation due to vaccine-preventable conditions for First Nations people were:

- chronic hepatitis B, accounted for 65% of all PPH due to vaccine-preventable conditions (3.8 PPH per 1,000 population)

- influenza, accounted for 19% of all PPH due to vaccine-preventable conditions (1.1 PPH per 1,000 population)

- pneumonia, accounted for 14% of all PPH due to vaccine-preventable conditions (0.8 PPH per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.12).

Comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

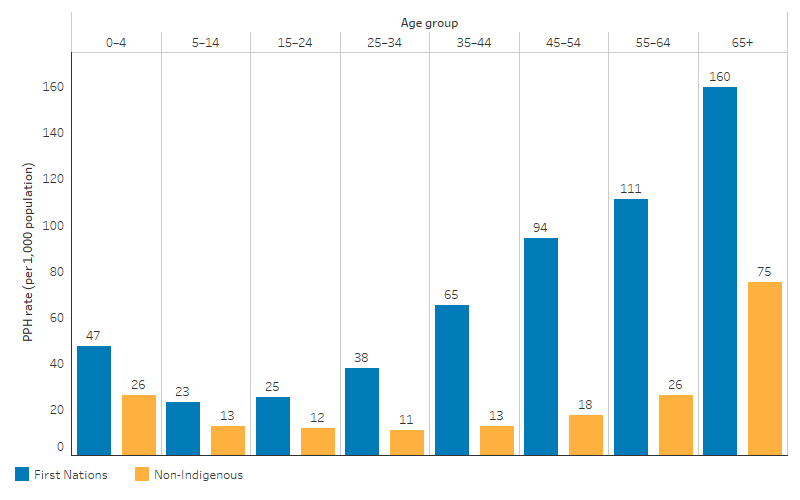

From July 2019 to June 2021, the PPH rates for First Nations people were higher compared with non-Indigenous Australians across all age groups (Table D3.07.1, Figure 3.07.6).

The relative difference in the PPH rate, measured by the rate ratio of First Nations people to non-Indigenous Australians, was largest for those aged 45–54. The rate for First Nations people in this age group was 5.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (94 compared with 18 PPH per 1,000 population). The smallest relative difference was for those aged 0–4 and 5–14. In both these age groups the rate for First Nations children was 1.8 times as high as for non-Indigenous children (Table D3.07.1).

The absolute gap in PPH rates, measured by differences for First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians, was largest for those in the 55–64 age group. For people aged 55–64, the absolute gap was 85 PPH per 1,000 population (111 compared with 26 PPH per 1,000 population). The smallest absolute gap was for those aged 5–14, where the absolute gap was 10 PPH per 1,000 population (23 compared with 13 PPH per 1,000 population) (Table D3.07.1).

Figure 3.07.6: Potentially preventable hospitalisation rate, by age group and Indigenous status, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.1. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019, 2022) for calculation of rates.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the PPH rate among First Nations people was 3 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.07.1).

Across states and territories, the age-standardised PPH rate for First Nations people ranged between 1.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (in Tasmania) to 4.3 times as high (in Western Australia) (Table D3.07.2, Figure 3.07.7).

Figure 3.07.7: Age-standardised potentially preventable hospitalisation rate, by jurisdiction, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.07.2 and Table D3.07.3. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019, 2022) for calculation of rates.

The age-standardised rates of PPH for First Nations people were higher than the rates for non-Indigenous Australians across all remoteness areas, with larger differences in remote than non-remote areas. Compared with non-Indigenous Australians, the age-standardised rate of PPH for First Nations people was 4.4 times as high in Remote areas and 4.2 times as high in Very remote areas (Table D3.07.3).

Across all the 10 most common causes of PPH for First Nations people, non-Indigenous Australians had lower PPH rates than First Nations people (based on age-standardised rates). The largest relative difference was for chronic hepatitis B, for which the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations for First Nations people was 8.2 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians. This was followed by COPD, for which the age-standardised PPH rate was 6.0 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.07.5).

Changes over time

Over the period 2013–14 to 2020–21, the age-standardised rate of potentially preventable hospitalisations for First Nations people increased by 13%. From 2013–14 to 2018–19, the age-standardised rate of PPH among First Nations people increased from 63 to 75 PPH per 1,000 population, before decreasing to 73 PPH per 1,000 population in 2019–20 and to 68 PPH per 1,000 population in 2020–21, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic (Table D3.07.11). This decrease was mainly due to a decrease in vaccine-preventable hospitalisations. Between 2013–14 and 2017–18, the number of hospitalisations from vaccine-preventable conditions among First Nations people increased from about 3,600 hospitalisations to about 6,600 hospitalisations, with a broadly similar number in 2018–19 (6,500 hospitalisations), before declining to about 4,000 hospitalisations in 2020–21. The age-standardised rate of vaccine-preventable PPH among First Nations people declined from 10.9 to 6.5 PPH per 1,000 population between 2018–19 and 2020–21 (Table D3.07.8).

A similar pattern was seen for PPH due to chronic conditions, though the decrease was smaller. For First Nations people, the number of PPH due to chronic conditions generally increased from about 13,500 hospitalisations to about 19,000 between 2013–14 and 2018–19, then declined to about 18,400 in 2020–21. The age-standardised rate of PPH due to chronic conditions for First Nations people increased from 31 to 36 PPH per 1,000 population between 2013–14 and 2018–19, with a subsequent drop to 33 per 1,000 population in 2020–21 (Table D3.07.9).

The age-standardised rate of PPH due to acute conditions among First Nations people increased between 2013–14 and 2018–19 (from 25 to 30 PPH per 1,000 population), with rates in 2018–19 and 2020–21 (29 and 30 per 1,000 population respectively) similar to that in 2018–19.

The decrease observed in PPH between 2018–19 and 2020–21 coincides with the COVID-19 pandemic. Public health measures put in place to control the pandemic, such as physical distancing, international and local travel restrictions, lockdowns, mask-wearing and handwashing, would have also affected the spread of other infectious diseases, particularly respiratory viruses (Sullivan et al. 2020). For example, nationally (for First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians), influenza fell from a 5-year average of 163,000 notifications per year over 2015–2019 to 21,363 in 2020 and 731 in 2021. The majority of influenza notifications in 2020 occurred in the first 3 months of the year, before the first lockdowns began. In 2020–21, there were only 368 hospitalisations nationally for influenza (AIHW 2022b).

In addition, people may have been less likely than usual to seek hospital care, which may also affect the PPH rates.

For non-Indigenous Australians, a similar pattern was seen – the age-standardised rate of PPH increased from 23 to 27 PPH per 1,000 population between 2013–14 and 2017–18, with a slightly lower rate in 2018–19 at 26 PPH per 1,000 population, and then decreased to 22 PPH per 1,000 population in 2020–21 (Table D3.07.11).

The absolute gap (rate difference) in PPH between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians widened between 2013–14 and 2018–19, (from 40 to 49 PPH per 1,000 population), with a small decrease between 2018–19 and 2020–21 (from 49 to 46 PPH per 1,000 population).

The relative difference (rate ratio) generally increased between 2013–14 and 2020–21, from 2.7 to 3.1 (Table D3.07.11, Figure 3.07.8).

Figure 3.07.8: Age-standardised rates of potentially preventable hospitalisations, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2013–14 to 2020–21

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (PPH per 1,000 population) for First Nations people minus the age-standardised rate (PPH per 1,000 population) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for First Nations people divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D3.07.11. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections for calculation of rates.

Research and evaluation findings

A prevalence study of linked public hospital data examined sociodemographic variations in the amount, duration and cost of PPH for chronic conditions among First Nations and non-Indigenous South Australians. Disparities in length of stay (LOS) and hospital costs of PPH for selected chronic conditions among First Nations and non-Indigenous South Australians were found, with disparities increasing with level of socioeconomic disadvantage and remoteness. First Nations people’s heightened risk of chronic PPH resulted in more time in hospital and greater cost. Systematic disparities in chronic PPH by Indigenous status, area of disadvantage and remoteness highlight the need for improved uptake of effective primary care. Routine, regional reporting will help monitor progress in meeting these population needs (Banham et al. 2017).

Another study showed that vulnerable groups (including refugees and First Nations people) were more likely to have excess emergency department (ED) visits for a range of issues that were potentially better addressed through primary and community health care. First Nations people had the highest rates of ambulatory care sensitive condition (i.e. potentially preventable) presentations to the ED with twice the risk of multiple presentations. Inequities in the uptake of effective primary care could generate excess burden and costs to the public hospital system (Banham et al. 2019).

There is a significant gap between health outcomes in First Nations children and non-Indigenous children in Australia, which may relate to inequity in health service provision, particularly in remote areas. A systematic review that examined health services and their use by children living in remote Australia identified that existing services were struggling to meet the demand. The review found that barriers to effective child health service delivery in remote Australia include the availability of trained staff, limited services and difficult access. Best practice service models that include community leadership and collaboration with a focus on primary prevention and health promotion are essential (Dossetor et al. 2021).

First Nations people have high rates of avoidable hospital admissions for chronic conditions; however, little is known about the frequency of avoidable admissions for this population. A study that examined trends in avoidable admissions among First Nations people and non-Indigenous people with chronic conditions in New South Wales, concluded that First Nations people were significantly more likely to experience frequent avoidable admissions over a 9-year period compared with non-Indigenous people. These high rates reflect the need for further research into which interventions are able to successfully reduce avoidable admissions among First Nations people, and the importance of culturally appropriate community health care (Jayakody et al. 2020).

In addition to culturally safe clinical services, ACCHSs provide health promotion, prevention and early intervention, continuity and coordination of care, among other services. Their model of comprehensive primary health care and community governance has reduced barriers to accessing care and unintentional racism, progressively improving individual health outcomes for First Nations people. ACCHSs have been shown to be strong in the completion of health checks and outperformed mainstream general practice in the identification and management of client risk factors, and ACCHSs have shown a strong commitment to continuous quality improvement. ACCHSs are significant employers of First Nations people and have had a major role in Aboriginal health worker training (Panaretto et al. 2014).

Research by Harrold et al. (2014) found that the rate of PPH for First Nations people was 2.16 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians who lived in the same Statistical Local Area in New South Wales, after controlling for age and sex (Harrold et al. 2014). The disparity was greatest in rural and remote areas relative to major cities. The largest differences in PPH were for diabetes complications, COPD and rheumatic heart disease. Geospatial analysis of PPH data can help identify areas where greater effort is needed to target the determinants of disease and to better manage chronic disease through culturally appropriate primary health care (Harrold et al. 2014).

An Australian study found that there were substantial inequalities in paediatric avoidable hospitalisations between First Nations and non-Indigenous children, regardless of where they live. The avoidable hospitalisation rates were found to be almost double in First Nations children compared with non-Indigenous children aged less than 2. Respiratory and infectious conditions were the most common reason for hospitalisation for children of all ages in the study, with First Nations children being more likely to be hospitalised for all conditions (Falster K et al. 2016).

First Nations people have access to an annual health check specifically tailored to their needs, funded through Medicare. The health check can help identify whether a person is at risk of developing illnesses or chronic conditions. If required, the person may also be referred to other healthcare professionals, such as physiotherapists, podiatrists, or dietitians, for free follow-up care.

A study in New South Wales found that personal sociodemographic and health characteristics are major drivers of geographic variation in PPH rates, and explain more of the variation than general practitioner (GPs) supply (Falster M et al. 2015). These personal characteristics (which included age, sex, Indigenous status, highest level of education, annual household income, level of psychological distress and more) also explained a greater amount of the variation for chronic conditions than for acute or vaccine-preventable conditions.

A retrospective analysis explored the geographical variations of hospital admissions for dental conditions across Australia (not only for First Nations people) from 2010–2011 to 2014–2015. It revealed 316,937 hospital admissions for dental conditions over the 5-year period, with a higher rate in Remote and Very remote areas (4.1 per 1,000 population) compared with Major cities (2.5 per 1,000). The most affected group was children aged 0–14 years in remote regions, with dental caries (including tooth decay or dental cavities) being the predominant cause of admission. The study specifically highlighted disparities in oral health and access to dental care in these regions, affecting groups including First Nations people (Crocombe et al. 2019).

Several factors contribute towards the poorer oral health of First Nations children, including social disadvantage and lack of access to appropriate diet and dental services. Since 2007, the Australian Government has helped fund oral health services for First Nations children aged under 16 in the Northern Territory. The Northern Territory Remote Aboriginal Investment Oral Health Program (NTRAI OHP) complements the Northern Territory Government Child Oral Health Program by providing preventive (application of full-mouth fluoride varnish and fissure sealants) and clinical (tooth extractions, diagnostics, restorations and examinations) services. The NTRAI OHP services are provided across the Northern Territory, in multi-chair community clinics as well as single-chair clinics in urban and regional primary schools. To improve access to oral health services in remote areas, single-chair clinics are also found in remote community health centres or delivered through mobile dental trucks. From March 2009 to December 2021, the proportion of children with tooth decay experience fell for most ages, though it rose from 82% to 84% for children aged 10, 69% to 71% for children aged 11 and 75% to 80% for children aged 15. Changes over time could be either associated with changes in the sample of children who were in the program at different times, or due to actual changes in tooth decay experience among children in the program (AIHW 2022).

A historical cohort study of First Nations residents living in remote Northern Territory communities from 2002 to 2011 found that those who utilised primary health care at medium/high levels were less likely to be admitted to hospital (and to die) than those in the low utilisation group. Higher levels of primary care utilisation for renal disease reduced avoidable hospitalisations by 82%–85% and for ischaemic (coronary) heart disease the reduction was 63%–78%. Primary health care in remote First Nations communities was shown to be associated with cost-savings to public hospitals and health benefits to individual patients. Investing $1 in primary care in remote First Nations communities could save $3.95–$11.75 in hospital costs, in addition to health benefits for individual patients (Zhao et al. 2014).

COPD is a preventable and yet irreversible chronic lung disease and one of the most common conditions responsible for PPH, which is characterised by chronic airway obstruction and airflow limitation, giving rise to shortness of breath, chronic cough and mucous production along with considerable impact on quality of life. Rates of COPD for First Nations people are disproportionally higher when compared with non-Indigenous Australians, and more so among First Nations people residing in the Northern Territory. In a 15-month study conducted in the Top End Health Service region of the Northern Territory, researchers assessed COPD disease awareness among 86 First Nations and non-Indigenous patients. They found a significant disparity in COPD knowledge, with 68% of First Nations participants and 19% of non-Indigenous participants reporting little to no knowledge of the disease. Despite the widespread use of puffers/inhalers, only 18% adhered to their therapy. Shortness of breath was the most common symptom leading to hospital presentations. Notably, First Nations patients expressed a preference for being managed in their local communities during COPD exacerbations (flare-up of symptoms), although they were often transferred to tertiary centres. The findings emphasise the need for tailored and culturally appropriate initiatives to improve COPD knowledge and management for patients and health professionals. This will improve quality of life and reduce recurrent hospitalisations and healthcare costs (Pal et al. 2022).

Medication-related problems (MRPs) contribute significantly to preventable patient harm and global healthcare expenditure. A descriptive case study provided valuable insights into the effective management of MRPs among two cohorts, with one cohort being First Nations people. Conducted over a period from June 2018 to December 2021, it involved participants from the Indigenous Medication Review Service (IMeRSe) trial. In this cohort, pharmacists identified various MRPs, with non-adherence to medication, under-treatment, and the presence of toxicity or adverse reactions being the most notable problems. The study emphasises the proactive role of community pharmacists in identifying and addressing these MRPs, highlighting the importance of culturally responsive and patient-centred approaches in healthcare. Pharmacists' recommendations predominantly involved changes in pharmacotherapy, tailored to meet the unique health needs of First Nations people. This approach underlines the significance of understanding and respecting the cultural contexts and health requirements of First Nations communities. Overall, the study contributes to a positive and constructive understanding of healthcare provision among First Nations people, showcasing the effectiveness of community pharmacists in enhancing medication management and health outcomes in these communities (Collins et al. 2023).

All First Nations Australians are eligible for a First Nations-specific health check, which can be claimed by health services every 9 months, allowing First Nations people to receive more than one Health Check in a calendar year. Following a Health Check, First Nations people can access up to 5 follow-up allied health MBS items provided by a practice nurse or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioner. Following the MBS Review, this is due to increase to 10 items. The health check can help identify whether a person is at risk of developing illnesses or chronic conditions. An analysis by the AIHW of geographical variation in rates of First Nations-specific health checks, PPH and potentially avoidable deaths, found that – somewhat counter-intuitively – areas with the highest rates of First Nations health checks were often not those with the lowest rates of PPH and potentially avoidable deaths. However, the report notes that while the uptake of First Nations health checks has increased (national rates tripled between 2010–11 and 2016–17), it is reasonable to expect some lag time as to when positive effects on health outcomes, such as reduced PPH, could be seen. Note also that an increase in checks may not translate to quality of care provided. How effective health checks are at preventing PPH will also depend on the extent to which recommended follow-up care resulting from these health checks is completed. Preliminary analysis by the AIHW showed that areas where a relatively high proportion of health checks result in follow-up care also tend to be in areas with relatively high rates of PPH; this may be because more health checks are likely to result in follow-up care being recommended in areas with relatively poor health outcomes. Reasons for low PPH rates include effective local primary health care, people not being hospitalised when they should be, and Indigenous status under-identification in hospital records. Reasons for high PPH rates include ineffective or culturally unsafe local primary health care, high prevalence of certain diseases or conditions and high rates of inter-hospital transfers. The importance of these factors is not well understood and further investigation is needed into how they impact on PPH rates for First Nations people (AIHW 2019).

Please refer to measure 1.24 Avoidable and preventable deaths for more information on relevant evaluations.

In 2017, the Australian Government announced it was undertaking a national evaluation of its investment in Aboriginal and Torres Islander primary health care which occurs primarily through the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP). The evaluation has a whole of system, person-centred approach that not only focuses on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the IAHP, but its interactions and influence on other parts of the primary health care and wider health system. The evaluation is drawing on the perspectives of First Nations stakeholders at different levels of the system and aims to facilitate learning across these levels. This evaluation is composed of 2 separate pathways, one looking at monitoring and evaluation, and the second looking at economic evaluation.

The monitoring and evaluation pathway is framed by 4 key evaluation questions:

- How well is the IAHP enabling the primary health care system to work for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

- What difference is the IAHP making to the primary health care system?

- What difference is the IAHP making to the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

- How can faster progress be made towards improving the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

The Department of Health and Aged Care is working with the IAHP Yarnes Health Sector Co-design Group on finalising the evaluation in 2024.

Phase 1 of the economic evaluation pathway has been published (Department of Health 2018) and showed:

- The analysis of national data for this project found a preventative effect upon hospitalisations from ACCHSs care.

- Provision of care through mainstream services is likely to be associated with worse health outcomes for First Nations people because mainstream services provide a less comprehensive and less integrated approach.

- First Nations people may face financial difficulties in accessing mainstream services, and if reliance were to be placed on mainstream services in lieu of ACCHSs, reduced attendance and adherence to treatment is highly likely due to services that may not meet their cultural needs and expectations (Dalton et al. 2018).

Implications

In Australia, data on PPHs are collected routinely by the AIHW and used as an indicator of primary health care accessibility and effectiveness. Targeting reduction in PPH is a specific objective of health care reform in Australia, with the aim of improving patients’ outcomes, reducing pressure on hospitals and enhancing health system efficiency and cost-effectiveness (Katterl et al. 2012). PPH rates have typically been seen as useful indicators of the effectiveness of, or access to community-based health services (Passey et al. 2015). The rates of PPH for First Nations people are considerably higher than rates for non-Indigenous Australians, particularly in Remote and Very remote areas. An AIHW report highlights opportunities that exist to prevent hospitalisations through primary health care interventions including:

- reducing and managing risk factors for disease

- vaccination

- oral health checks

- lifestyle interventions

- management of chronic conditions

- antenatal care (AIHW 2020).

Several studies have found that improving patient-provider communication and collaboration makes it easier for people to navigate, understand and use information and services to take care of their health. This requires patient-centred innovation in the health system, particularly innovations addressing patient-centred goals of improved access, continuity, communication and coordination, cultural competency, and family- and person-focused care over time. The research also provides some evidence of solutions including efforts to promote patient–professional communication and collaboration to bring about a more active role for patients and to support self-care (Hernandez et al. 2012; Øvretveit 2012).

For First Nations children, there is scope to reduce PPH though targeted prevention, early intervention through primary health care and better access to treatment for common childhood conditions. Policy measures that aim to reduce disparities in social determinants (such as access to better housing) may also help to reduce the incidence of these conditions in First Nations children.

Research has started to show that geographic variation in PPH may not be simply explained by the supply of GPs. PPH may be more a reflection of social determinants and individual health factors, particularly for chronic conditions, than access to GPs (Falster et al. 2015). PPH may, therefore, indicate areas where primary health care could be more effective or where it may be underutilised. There is a need for improvements in efforts to address cultural and social determinants of health beyond the health sector. These efforts should include partnerships with the First Nations community-controlled health sector, as providers of comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care.

The data in this measure has illustrated the high rate of PPH for First Nations people, indicating that primary health care is not adequately meeting the need. Further research is needed using data linkage to understand the patient journey throughout the health system, at smaller levels of geography across Australia. This should include measures of social determinants, and primary care utilisation to explore areas of unmet health need or underutilised health care for First Nations people.

Understanding the reasons for underutilisation of primary health care at the local level is important in order to address barriers to accessing care (see measure 3.14 Access to services compared with need) such as distance, cost, availability, racism and cultural safety.

First Nations people’s health checks under MBS items 715 or 228 encourage early detection, diagnosis and intervention for common and treatable conditions that cause considerable morbidity and early mortality. There are also incentives to encourage bulk billing of Health Assessments. First Nations patients who have received a health check can be referred by their GP to eligible allied health professionals for up to 5 services per calendar year using MBS items 81300–81360. Patients who have received an MBS item 715 or 228 can also receive up to 10 follow-up services per calendar year from a practice nurse or registered Aboriginal Health Worker, on behalf of their General Practitioner under MBS item 10987.

The National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) are currently updating the National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People (4th Edition). The National Guide is a practical resource intended for all health professionals delivering primary healthcare to First Nations people. The recommendations aim to prevent disease, detect early and unrecognised disease, and promote health. The National Guide emphasises that a culturally supportive and culturally safe environment needs to be established and continuously demonstrated. The National Guide also includes the templates used to administer First Nations health checks, see: Resources to support health checks for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. The 4th edition of the National Guide will be titled the National guide to preventive healthcare for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and is due for public release in 2024 along with updated health check templates. The health check templates refer to both the National Guide and the Central Australian Rural Practitioner’s Association (CARPA) standard treatment manual.

ACCHSs play an essential role in providing comprehensive, appropriate and culturally safe care for First Nations people. The evaluations in measure 1.24 Avoidable and preventable deaths point to mainstream services being less effective than ACCHSs. Comprehensive, accessible and well-integrated care is needed, particularly in managing chronic conditions, in order to prevent hospitalisations and death from avoidable causes.

Ensuring services are accessible and appropriate is therefore important to drive reductions in PPH and avoidable deaths. ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. The Australian Government committed to building a strong and sustainable First Nations community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people across the country under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Further work to ensure mainstream services can provide culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations people is also critically important. These 2 dimensions of health care for First Nations people have been emphasised in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course.

The Health Plan states that early intervention is vital to manage the development or progression of health conditions over time. A key focus must be on the conditions with the potential to become serious, but that are preventable and/or easily treatable with early intervention. Early intervention approaches must be determined locally to be effective and be place-based. Access to culturally safe and responsive, best practice early intervention must continue to be enhanced to ensure early identification of risk factors and proactive management of chronic disease, including by prioritising the delivery of care through ACCHSs. There must also be a focus on ensuring accessible culturally safe primary health care services for First Nations communities across all stages of life, and particularly in childhood to provide the greatest protection across the life course. Targeted, culturally and linguistically responsive health promotion activities are vital for First Nations young people transitioning into adulthood. Integrated, cross-sectoral care must be embedded to ensure that First Nations people have greater access to culturally safe and inclusive care pathways through early intervention, aftercare and post intervention services, no matter where they live (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

Implementation of the Health Plan is driving structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism, provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities. The Priorities of the Health Plan span 4 high-level categories: the enablers for change; focusing on prevention; improving the health system; and a culturally informed evidence base. Focusing on prevention covers:

- Priority 4: Health promotion

- Priority 5: Early intervention

- Priority 6: Social and emotional wellbeing and trauma-aware, healing-informed approaches

- Priority 7: Healthy environments, sustainability and preparedness.

ACCHSs advocate for and deliver person-centred and community-centred programs. These include health promotion and illness prevention, integrated family and community services, and action on the cultural determinants and social determinants of health. In this way, the ACCHSs model of care goes beyond what mainstream primary care services typically deliver.

As part of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, the community-controlled health sector was identified as one of four initial sectors for joint national strengthening effort and the development of a 3-year Sector Strengthening Plan. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) was developed in 2021, to acknowledge and respond to the scope of key challenges for the sector, providing 17 transformative sector strengthening actions. Developed through strong consultation across the First Nations community-controlled health sector and other First Nations health organisations, the Health-SSP will be used to prioritise, partner and negotiate beneficial sector-strengthening strategies.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 - 2031. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2022. National, state and territory population, Reference Period September 2022. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019a. Potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia by age groups and small geographic areas, 2017–18. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed May 2020.

- AIHW 2019b. Regional variation in uptake of Indigenous health checks and in preventable hospitalisations and deaths. Cat. no. IHW 216. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2020. Disparities in potentially preventable hospitalisations across Australia: Exploring the data. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed May 2020.

- AIHW 2022a. National Healthcare Agreement: PI 18–Selected potentially preventable hospitalisations, 2022. Viewed Feb 2024.

- AIHW 2022b. Infectious and communicable diseases. Viewed Feb 2024.

- AIHW 2022c. Oral health outreach services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the Northern Territory: July 2012 to December 2021. Canberra: AIHW.

- Banham D, Chen T, Karnon J, Brown A & Lynch J 2017. Sociodemographic variations in the amount, duration and cost of potentially preventable hospitalisation for chronic conditions among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians: a period prevalence study of linked public hospital data. BMJ Open 7:e017331.

- Banham D, Karnon J, Densley K & Lynch JW 2019. How much emergency department use by vulnerable populations is potentially preventable?: A period prevalence study of linked public hospital data in South Australia. BMJ Open 9:e022845.

- Collins JC, Hu J, McMillan SS, O’Reilly CL, El-Den S, Kelly F et al. 2023. Medication-related problems identified by community pharmacists: a descriptive case study of two Australian populations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Policy and Practice 16:133.

- Crocombe L, Allen P, Bettiol S, Khan S, Godwin D, Barnett T et al. 2019. Geographical variation in preventable hospital admissions for dental conditions: An Australia-wide analysis. Australian Journal of Rural Health 27:520-6.

- Dalton A, Lal A, Mohebbi M & Carter R 2018. Economic Evaluation of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme Phase 1 Report. Canberra: Department of Health.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2021. The new National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Viewed Feb 2024.

- Dossetor P, Thorburn K, Oscar J, Carter M, Jeffery H, Harley D et al. 2021. Health services for Indigenous children in remote Australia: a strategic literature review. Research Square.

- Falster K, Banks E, Lujic S, Falster M, Lynch J, Zwi K et al. 2016. Inequalities in pediatric avoidable hospitalizations between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in Australia: a population data linkage study. BMC pediatrics 16:169.

- Falster M, Jorm L, Douglas K, Blyth F, Elliott R & Leyland A 2015. Sociodemographic and health characteristics, rather than primary care supply, are major drivers of geographic variation in preventable hospitalizations in Australia. Medical care 53:436.

- Gibson O & Segal L 2009. Avoidable hospitalisation in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory. The Medical Journal of Australia 191:411.

- Harrold T, Randall D, Falster M, Lujic S & Jorm L 2014. The Contribution of Geography to Disparities in Preventable Hospitalisations between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians. PloS one.

- Hernandez SE, Conrad DA, Marcus-Smith MS, Reed P & Watts C 2012. Patient-centered innovation in health care organizations: A conceptual framework and case study application. Health Care Management Review.

- Jayakody A, Oldmeadow C, Carey M, Bryant J, Evans T, Ella S et al. 2020. Frequent avoidable admissions amongst Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people with chronic conditions in New South Wales, Australia: a historical cohort study. BMC health services research 20:1082.

- Katterl R, Anikeeva O, Butler C, Brown L, Smith B & Bywood P 2012. Potentially avoidable hospitalisations in Australia: Causes for hospitalisations and primary health care interventions. Adelaide: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service.

- Li SQ, Gray N, Guthridge S, Pircher S, Wang Z & Zhao Y 2009. Avoidable mortality trends in Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal populations in the Northern Territory, 1985‐2004. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33:544-50.

- Øvretveit J 2012. Summary of 'Do changes to patient-provider relationships improve quality and save money?'. London: The Health Foundation.

- Pal A, Howarth TP, Rissel C, Messenger R, Issac S, Ford L et al. 2022. COPD disease knowledge, self-awareness and reasons for hospital presentations among a predominately Indigenous Australian cohort: a study to explore preventable hospitalisation. BMJ Open Respir Res 9.

- Panaretto K, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring I 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

- Passey ME, Longman JM, Johnston JJ, Jorm L, Ewald D, Morgan GG et al. 2015. Diagnosing Potentially Preventable Hospitalisations (DaPPHne): protocol for a mixed-methods data-linkage study. BMJ Open 5:e009879.

- Sullivan S, Carlson S, Cheng A, Chilver M, Dwyer D, Irwin M et al. 2020. Where has all the influenza gone? The impact of COVID-19 on the circulation of influenza and other respiratory viruses, Australia, March to September 2020. Euro Surveill 25.

- Zhao Y, Thomas S, Guthridge S & Wakerman J 2014. Better health outcomes at lower costs: the benefits of primary care utilisation for chronic disease management in remote Indigenous communities in Australia's Northern Territory. BMC health services research 14:463.