Key messages

- After accounting for differences in age-structure between the two populations, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people experience a burden of disease and injury around 2.3 times as high as non-Indigenous Australians. In comparison, age-adjusted per person expenditure (excluding the Section 100 Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services Program (s100 RAAHS)) on pharmaceuticals for First Nations people was about 1.4 times the amount for non-Indigenous Australians, suggesting that expenditure is low compared with need.

- In 2022–23, for First Nations people, total expenditure on medicines through the PBS was $685 million nationally. This includes expenditure by the Australian Government and by individuals (through co-payments).

- Expenditure by the Australian Government on medicines under the PBS was $643 million – or $636 per First Nations person, compared with $627 per non-Indigenous Australian. The majority of government PBS expenditure for First Nations people were for scripts eligible for the CTG PBS Co-Payment Program, at $345 million total in 2022–23, or $341 per person.

- When calculated as expenditure per person, total PBS expenditure for First Nations people was highest in Major cities ($716 per person), followed by Inner and outer regional areas ($663 per person), and lowest in Remote and very remote areas ($610 per person). Across all remoteness areas per person PBS expenditure was lower for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians, with the greatest difference in Inner and outer regional areas (a difference of $226 per person).

- Between 2016–17 and 2022–23, age-standardised per person expenditure for First Nations people decreased by an average of 2.2% per annum, compared with an increase of 0.4% per annum for non-Indigenous Australians. The ratio of per person PBS expenditure for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians decreased from 1.6 to 1.4 between 2016–17 and 2022–23.

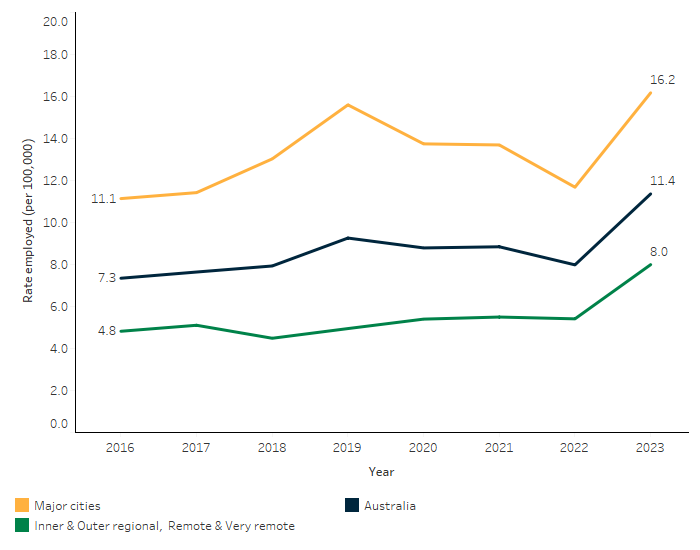

- Increasing the First Nations pharmacy workforce is crucial for providing culturally sensitive care, improving health-care access, and promoting health equity. In 2023, of the 29,582 pharmacists employed nationally, 116 (0.4%) were First Nations people – an increase from 66 First Nations pharmacists in 2016 (0.3%). The number of First Nations people employed as pharmacists per 100,000 population was higher in Major cities (16 per 100,000) than regional and remote areas (8 per 100,000).

- A study showed that the Closing The Gap (CTG) Co-payment program increased medication usage by 39% and decreased out-of-pocket expenses by 61% for First Nations people, with a 156% increase for non-concessional patients. Another study of the effect of the CTG Co-payment Incentive found that there were downward trends in hospitalisations among First Nations people for chronic conditions, relative to other hospitalisations, in areas with higher levels of CTG script uptake. The CTG Co-payment Incentive led to increased use of prescription medication and GP visits among First Nations people.

- Incarcerated First Nations people face significant systemic barriers to accessing health care, including PBS medication, within the prison system.

Why is it important?

Ensuring equitable access to essential medicines is vital for improving health outcomes, especially for the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases (like diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, and kidney failure) and other chronic health conditions. The World Health Organization (WHO)'s policy framework on medicine emphasises the importance of availability, affordability, quality, and proper use of these medicines (WHO 2017). The WHO framework on medicines states that essential medicines are intended to be available ‘at all times in adequate amounts, in the appropriate dosage forms, with assured quality and adequate information and at a price the individual and community can afford' (WHO 2004). Equitable access to essential medicines and other medical technologies depends on affordable pricing and effective financing. Promoting fair prices and cost-effective interventions is central to the achievement of universal health coverage. Affordable access to medicines is important for many acute and chronic illnesses. For chronic illnesses, multiple medications may be required for many years to avoid complications (WHO 2017).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people, who experience high rates of acute and chronic illnesses, access to necessary prescription medicines is particularly crucial. In Australia, the National Medicines Policy is a high-level framework focused on the availability and the use of medicines and medicines-related services. All Australians should have timely, safe, reliable and affordable access to effective and high-quality medicines and medicines services. One of the policy’s principles is focused on equity, highlighting that access to medicines services and medicines information should be culturally appropriate; and that First Nations leadership and self-determination is needed to identify priorities and drive solutions to addressing needs and barriers experienced by First Nations people (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022a).

The main mechanism for ensuring reliable, timely and affordable access to a wide range of prescription medicines is the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS). In 2022–23, the Australian Government subsidised 230.2 million prescriptions at the cost of approximately $17.0 billion (including the RPBS) (AIHW 2024a), of which $16.5 billion is spent through the PBS. The PBS includes specific listings for drugs identified as priorities for redressing the health inequities experienced by First Nations people. The PBS supports the treatment of conditions that are particularly prevalent in First Nations communities to ensure that essential medicines are accessible and affordable for those who need them most. Additionally, the Indigenous Access Program helps First Nations people understand the Medicare services available and their medication entitlements.

PBS medicines are dispensed mainly through community pharmacies, with some available to hospital day patients, in arrangements described under section 85 (s85) of the National Health Act 1953. Other subsidised medicines are available under alternative arrangements described in section 100 of the Act. These arrangements ensure the availability of pharmaceutical benefits in specific circumstances, such as for people living in isolated areas or those requiring treatment where standard PBS provisions are inadequate. Programs under section 100 include the Highly Specialised Drugs Program and the Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy, among others, ensuring tailored access to essential medications for those in unique or challenging situations.

The Community Service Obligation (CSO) Funding Pool continues to play a vital role in ensuring that PBS medicines are accessible to all Australians, including those in remote areas. As of January 2025, the CSO Funding Pool operates under the First Pharmacy Wholesaler Agreement (1PWA), a five-year agreement between the Australian Government and the National Pharmaceutical Services Association (NPSA). This agreement ensures that the rising costs of distributing medicines across Australia are not passed on to consumers. The CSO Funding Pool provides over $200 million annually to eligible distributors who meet specific service standards, ensuring timely delivery of PBS medicines to community pharmacies within 24 to 72 hours.

Complementing this program, the Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services (RAAHS, also known as Section 100 or s100) Program allows approved Aboriginal health services to provide medicines without the need for a normal PBS prescription form, and without charge (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a). The program addresses the lack of pharmacies in remote areas, ensuring First Nations people can access essential medicines.

Subsidised medicines can also be supplied through the Closing the Gap (CTG) PBS Co-payment program, which was established in July 2010 to improve access to affordable PBS medicines for First Nations people living with, or at risk of, chronic disease. The program has been expanded since 2020, so that access is not dependent on chronic disease status. Under this program, patient registration only needs to occur once and lasts for a patient’s lifetime. It allows any PBS medicine to be dispensed under the CTG program by community pharmacies, and private and public hospitals.

The Australian Government also contributes to the cost of PBS medicines supplied to outpatients and patients upon discharge from public hospitals in most jurisdictions, excluding New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, through the Pharmaceutical Reform Agreements (PRAs). However, from 1 January 2025, the patient co-payment for PBS medicines has been frozen at $31.60 for general patients and $7.70 for concession cardholders. Additionally, many public hospitals continue to waive the patient contribution for First Nations people.

It is important to note that expenditure on PBS medicines is not a direct reflection of the quantity of prescriptions as costs per prescription can change over time due to new medicines being listed on the PBS, or existing medicines becoming cheaper as they go off patent. However, price increases can occur due to factors such as changes in manufacturing costs, supply chain issues, or adjustments in pricing agreements. Similarly, the change in expenditure over time should be understood in this context, for example the 2016 listing of new direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) for treating hepatitis C led to a significant increase in government spending on the PBS. These treatments were highly effective but also expensive, which initially drove up costs. However, as the number of prescriptions for these treatments declined over time, the expenditure also decreased (AIHW 2020, 2024b). Understanding these dynamics is crucial for interpreting changes in PBS expenditure over time.

Increasing the First Nations pharmacy workforce is crucial for providing culturally sensitive care, improving healthcare access, and promoting health equity. First Nations pharmacists can enhance trust and communication, inspire more First Nations individuals to pursue healthcare careers, and play a vital role in community health education. This can lead to better health outcomes, greater healthcare equity, and stronger community ties, particularly in regional and remote areas where healthcare access is often limited (Gall et al. 2025; Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2025).

Ensuring equitable access to essential medicines is crucial for improving health outcomes, particularly for chronic illnesses. For First Nations people, who face higher rates of these conditions, having access to necessary prescription medications is vital for their well-being and quality of life.

Data findings

Expenditure

This section presents data on expenditure on medicines through the PBS, based on PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System (see Box 3.15.1 and data sources and quality).

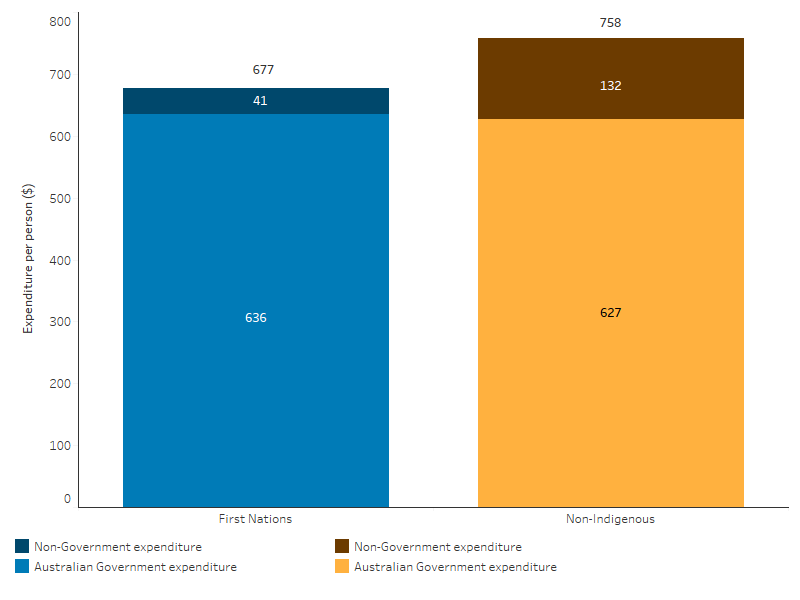

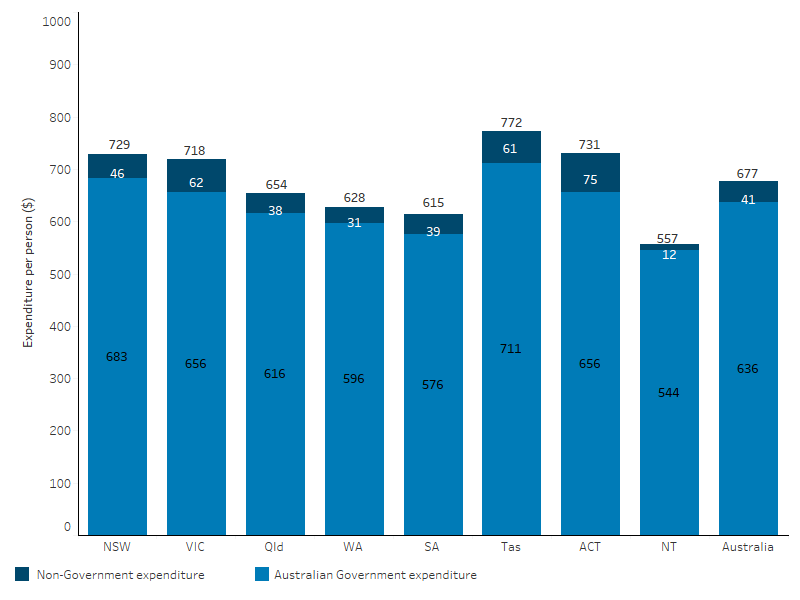

In 2022–23, for First Nations people, the total expenditure on medicines subsidised through the PBS was $685 million, which was an average of $677 per person. For non-Indigenous Australians, the average expenditure was $758 per person, representing a difference of $81 between First Nations and non-Indigenous expenditure per person on average, noting this ‘gap’ does not account for the different age structure of the First Nations population or the higher burden of disease experienced by this population (see Box 3.15.1 and Expenditure by age below) (Table D3.15.1, Figure 3.15.1).

The Australian Government covers the vast majority of expenditure on PBS medicines. For First Nations people, 94% (or $643 million) of the total PBS expenditure was by the Australian Government, while for non-Indigenous Australians it was 83%. The remaining costs are covered by individuals through co-payments. Australian Government expenditure on medicines subsidised through the PBS was $636 per person for First Nations people compared with $627 per person for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.15.1, Figure 3.15.1).

Figure 3.15.1: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person, by source and Indigenous status, 2022–23

Note: Components may not sum to the total due to rounding.

Source: Table D3.15.1. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

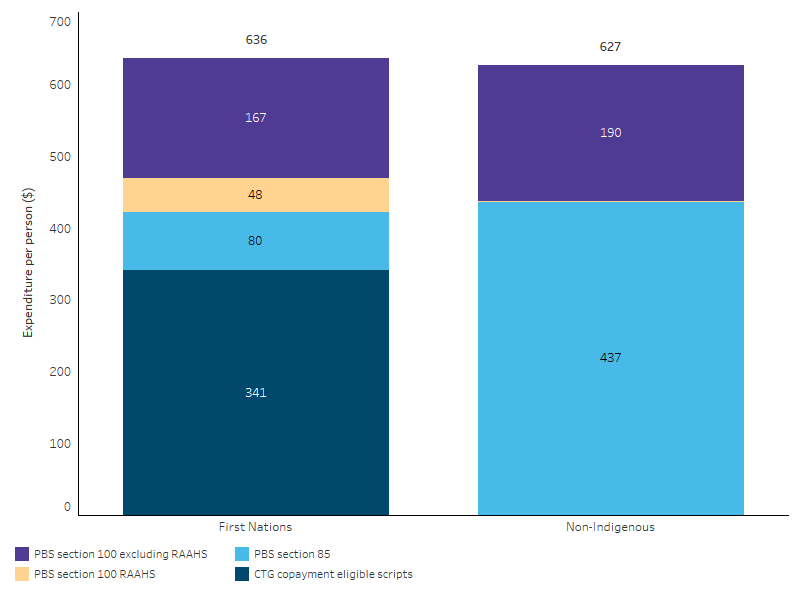

Just over half (54%) of Australian Government PBS expenditure for First Nations people was expenditure on scripts eligible under the CTG PBS Co-Payment Program, at $345 million total in 2022–23, or $341 per person (Table D3.15.1, Figure 3.15.2). This comprises a total of $281 million in benefits paid via the PBS and $64 million in co-payments under the program (Table D3.15.8).

The CTG PBS Co-payment program was established in 2010 to improve access to affordable PBS medicines for First Nations people living with, or at risk of, chronic disease, and in 2020 was expanded with access no longer dependent on chronic disease status. The program is available to First Nations people of any age who are registered with Medicare, and in the opinion of a prescriber or Aboriginal Health Practitioner (AHP):

- would experience setbacks in the prevention or ongoing management of a condition if the person did not take their prescribed medicine; and

- are unlikely to adhere to their medicines regimen without assistance through the program (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a).

For non-Indigenous Australians, the largest part of government expenditure was under PBS section 85, which are ‘General Schedule’ medicines dispensed by community and hospital pharmacies. This makes up a smaller share of expenditure for First-Nations people as both the CTG PBS Co-Payment and RAAHS programs include access to section 85 medicines (Table D3.15.1, Figure 3.15.2).

Expenditure on PBS section 100 items (excluding spending on the CTG Co-Payment and RAAHS programs) represented a similar proportion of government expenditure for both First Nations people (26%) and non-Indigenous Australians (30%) (Table D3.15.1, Figure 3.15.2). This covers medicines which require special storage or dispensing, specialist monitoring during treatment, or administration in a hospital outpatient setting, as well as medicines listed for the treatment of complex conditions (chronic conditions and cancer) where they are supplied mostly through hospitals and administered under specialised medical supervision (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a). From 1 July 2024, the CTG PBS Co-Payment program was expanded to also apply to section 100 PBS medicines dispensed by community pharmacies, approved medical practitioners and private hospitals (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a).

Figure 3.15.2: Australian Government Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person, by program and Indigenous status, 2022–23

Note: S100 Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services (RAAHS) Program expenditure for non-Indigenous Australians is relatively small (<$1 per person) and so is barely visible in the figure but is included in the total.

Source: Table D3.15.1. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

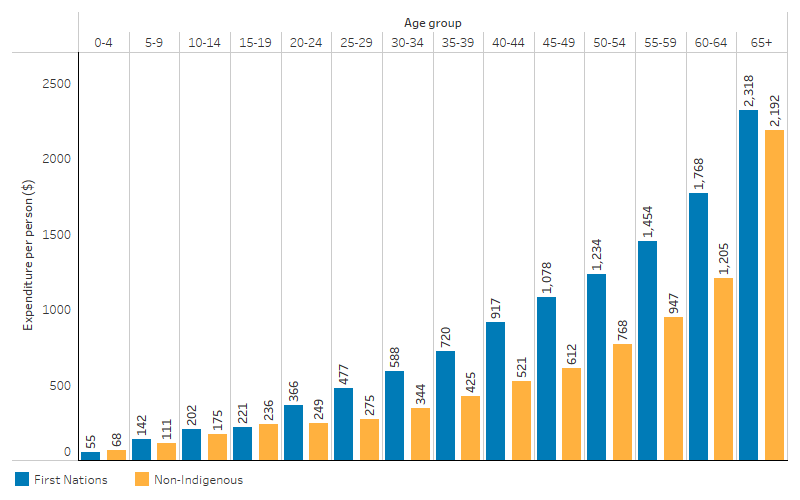

Expenditure by age

Expenditure on PBS items can be allocated to age groups for all medicines except those provided through approved Aboriginal Health Services under the s100 RAAHS, as RAAHS data were not available by age. This means that the following data underestimate true per person expenditure for First Nations people.

In 2022–23, per person expenditure on medicines subsidised through the PBS (excluding the s100 RAAHS) was higher for First Nations people in all age groups except for those aged 0–4 and 15–19, in which higher non-Indigenous expenditure was driven by higher individual (as opposed to government) spending (Table D3.15.7). Per person expenditure increased with age for both First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 3.15.3).

Figure 3.15.3: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person (excluding s100 RAAHS), by age group and Indigenous status, 2022–23

Note: Excludes s100 Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services Program (RAAHS) expenditure as this cannot be apportioned by age.

Source: Table D3.15.7. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

After adjusting for differences in the age-structure between the two populations, total per person expenditure on PBS medicines (excluding the s100 RAAHS) for First Nations peoples was 1.4 times that for non-Indigenous Australians.

Breaking it down further:

- Per person expenditure by the Australian Government for First Nations people was 1.6 times that for non-Indigenous Australians.

- Non-government expenditure (individual contributions) for First Nations people was 0.4 times that for non-Indigenous Australians (60% lower) (Table D3.15.7).

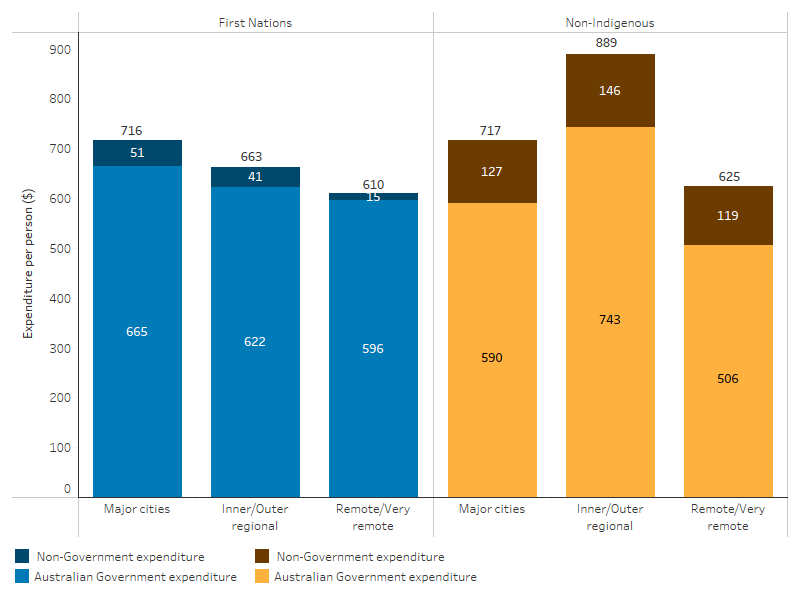

Expenditure by remoteness

The following PBS data should be interpreted with caution given limitations of the geographic information used. PBS expenditure by remoteness is based on the postcode of a person’s mailing address. However, if the mailing address is a PO Box, the postcode may not reflect where the person lives. Additionally, some postcodes span multiple remoteness categories, so expenditure is distributed between these areas based on population estimates. Expenditure with an unknown remoteness has been excluded from the analysis.

In 2022–23, total expenditure per person through the PBS for First Nations people was highest in Major cities ($716), followed by Inner and outer regional areas ($663) and Remote and very remote areas ($610) (Table D3.15.3, Figure 3.15.4).

In 2022–23, Australian Government expenditure per person through the PBS for First Nations people was highest in Major cities ($665), followed by Inner and outer regional areas ($622) and Remote and very remote areas $596). Non-government expenditure for First Nations people was also highest in Major cities ($51 per person), and lowest in Remote and very remote areas ($15 per person).

In 2022–23:

- Australian Government per person PBS expenditure was higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians in Major cities, and Remote and very remote areas

- non-government per person PBS expenditure was lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians across all remoteness areas

- overall per person PBS expenditure was similar for First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians in Major cities, and lower for First Nations people in Inner and outer regional and Remote and very remote areas (Table D3.15.3, Figure 3.15.4).

Note that these data have not been age-standardised.

Figure 3.15.4: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person, by remoteness, source of funding and Indigenous status, 2022–23

Note: Remoteness area is derived from mailing address postcode.

Source: Table D3.15.3. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

Expenditure by state and territory

In 2022–23, total per person expenditure on PBS medicines for First Nations people varied across jurisdictions, from $557 per person in the Northern Territory to $772 per person in Tasmania. Australian Government expenditure was highest per person in Tasmania ($711), while non-government expenditure was highest in the Australian Capital Territory ($75). Both Australian Government and individual expenditure were lowest in the Northern Territory ($544 and $12 per person, respectively) (Table D3.15.2, Figure 3.15.5).

Figure 3.15.5: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person for First Nations people, by jurisdiction and source of funding, 2022–23

Note: Jurisdiction is derived from mailing address postcode.

Source: Table D3.15.2. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

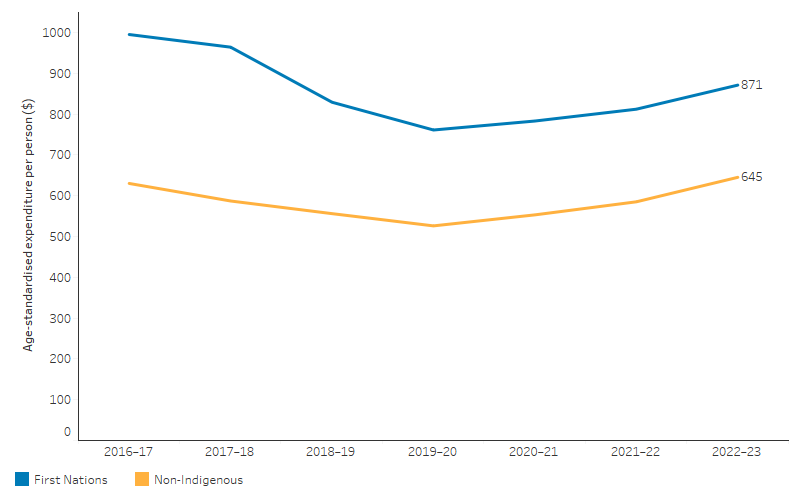

Changes over time

Expenditure in this section has been age-standardised to adjust for differences in age structure between the First Nations population and non-Indigenous populations, and changes in age structures over time. Expenditure on s100 RAAHS has been excluded, as these data are not available by age. This means that the following data underestimate true per person expenditure for First Nations people. For trends based on unadjusted expenditure (including s100 RAAHS), see Table D3.15.4. The data in this section have also been adjusted for inflation.

These per person trends are limited to 2016 onwards, due to a large non-demographic increase in Census counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people between 2016 and 2021 (see Understanding change in counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Guide to using historical estimates for comparative analysis and reporting.

Between 2016–17 and 2019–20, age-standardised per person expenditure on PBS subsidised medicines for First Nations people decreased in real terms (by an average of 8.6% per year). This trend then shifted, with an increase in each year between 2019–20 and 2022–23 (4.6% per year in real terms), though per person expenditure remained lower than in 2016–17. A similar pattern was observed for non-Indigenous Australians, though the size of the change was smaller. Overall, between 2016–17 and 2022–23, age-standardised expenditure for First Nations people decreased by an average of 2.2% per annum, compared with an increase of 0.4% per annum for non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 3.14.6, Table D3.15.4).

It should be noted that part of the decrease in expenditure at the start of this period is likely due to the declining number of prescriptions for hepatitis C treatments supplied through the PBS. When new treatments for hepatitis C were listed on the PBS in 2016, there was a rapid initial uptake, which significantly reduced the number of Australians living with hepatitis C. This led to a subsequent decrease in the number of prescriptions and, consequently, a reduction in expenditure (Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a).

The ratio of per person PBS expenditure for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians decreased from 1.6 to 1.4 between 2016–17 and 2022–23 (based on inflation adjusted and age-standardised data, and excluding the s100 RAAHS) (Table D3.15.4).

Figure 3.15.6: Total Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure per person (age-standardised, excluding s100 RAAHS), by Indigenous status, 2016–17 to 2022–23 (inflation adjusted)

Note: Expenditure from 2016–17 to 2022–23 is expressed in 2022–23 prices, adjusted for inflation.

Source: Table D3.15.4. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System; and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

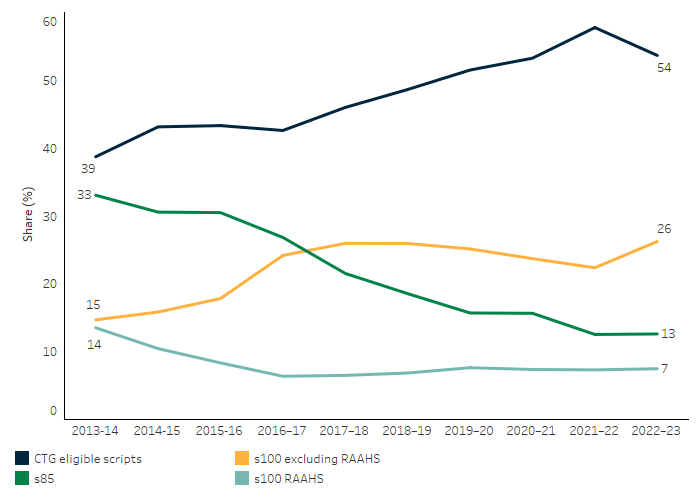

Trends in Australian Government PBS expenditure

Calculated using age-standardised and inflation adjusted data (excluding the s100 RAAHS), the Australian Government’s per person expenditure on PBS medicines for First Nations people decreased by an average of 2.0% per year between 2016–17 and 2022–23.

In contrast, for non-Indigenous Australians, it grew by an average of 0.8% per year (Table D3.15.4). The ratio of Australian Government per person PBS expenditure for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians (excluding the s100 RAAHS) decreased from 1.8 to 1.6 (Table D3.15.4).

Over the past decade the composition of Australian Government expenditure on PBS medicines for First Nations people has evolved. From 2013–14 the share of expenditure going to General Schedule (s85) medicines has declined markedly, from 33% in 2013–14 to 13% in 2022–23. This has been matched by a corresponding increase in the share of expenditure going to PBS scripts eligible for the CTG Co-payment, which has increased from 39% to 54% over this same period (Figure 3.15.7, Table D3.15.9). Section 100 medicines (excluding the s100 RAAHS) have also made up an increasing share of Australian Government expenditure on PBS medicines for First Nations Australians.

Note that changes in program expenditure over time should be interpreted with caution due to changes in eligibility and administration of these programs. For example, in July 2021 all CTG Co-payment patient registration details were moved to a centralised database (Australian Medical Association 2021). This may have impacted the data on uptake of CTG Co-payment eligible scripts at this time.

Figure 3.15.7: Australian Government Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme expenditure for First Nations people, share by program, 2013–14 to 2022–23

Source: Table D3.15.9. AIHW analysis of the PBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse and Financial Journaling System.

Use of medications and having prescriptions filled

Results from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS) showed that 50% of First Nations people (or around 214,900 people) aged 15 and over living in non-remote areas reported having taken medications over the past 2 weeks (including 36% who had taken only medications and 14% who had taken both medications and supplements). The proportion who reported having taken medications over the past 2 weeks was higher for First Nations women than men (54% and 45% respectively). The proportion who reported having taken medications over the past 2 weeks increased with age, from 31% for those aged 15–24 to 77% for those aged over 55 (Table D3.15.6).

In 2018–19, 86% of First Nations people (or around 373,100 people) aged 15 and over (and living in non-remote areas) reported having had their prescriptions filled in the last 12 months. This increased from the 81% that was reported in the 2012–13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Table D3.15.5, HPF 2017 Table 3.15.5). First Nations men were more likely than First Nations women to report having filled their prescriptions (89% compared with 83%, respectively). The most common reasons reported by First Nations people for not having a prescription filled in the last 12 months were because of cost (36%, or about 21,500 people), they decided they didn’t need it (30%, or about 17,900 people), they didn’t want to (15%, or about 9,000 people) or they were too busy (11%, or about 6,400 people) (Table D3.15.5).

Medications in prison

People in prison often have substantial and complex health needs, including higher rates of mental health disorders, chronic physical health conditions, and communicable disease than the general population (AIHW 2023). Medications are an important element in treating many physical and mental health conditions.

Medications provided to people in prison are not covered by the PBS (except for medications that fall under Schedule 100 of the PBS, known as the Highly Specialised Drugs Program) and are instead funded through the state and territory governments. Certain aspects of the prison environment may influence prescribing practices. People in prison have limited access to over-the-counter medications, and are usually not allowed to keep medications in their possession; hence, some medications that may be purchased without prescription in the community are likely to be prescribed in prison.

The National Prisoner Health Data Collection (NPHDC) includes data on prescription medications dispensed to incarcerated individuals on a single day during the data collection period in 2022. This provided a snapshot of the medications typically dispensed by prison clinics. However, the results may underestimate the true proportions of incarcerated individuals taking prescription medication, as not all prison clinics were able to capture all dispensed medications.

On the snapshot day in 2022, 20% of First Nations people in custody were dispensed prescription medicine in prison, compared with 23% of non-Indigenous people in custody (AIHW 2023: Table S142).

The most commonly dispensed medication type for First Nations people in custody was antidepressants/mood stabilisers (for example, sertraline, fluoxetine) (20%), followed by analgesics (for example, paracetamol, codeine, oxycodone) (12%), anti-inflammatories/anti-rheumatic agents (for example, ibuprofen, aspirin) (8.0%), and antihypertensives or beta blocking agents (for example, perindopril, ramipril) (7.6%) (AIHW 2023: Table S143). This is similar to the distribution of medications most commonly dispensed to non-Indigenous people in custody.

First Nations pharmacists

In 2023, out of the 29,582 pharmacists employed nationally, 116 (0.4%) were First Nations people. The number of First Nations pharmacists employed nationally has increased from 66 (0.3%) in 2016 to 116 in 2023 – corresponding to an increase in the rate of First Nations pharmacists from 7.3 per 100,000 in 2016 to 11.4 per 100,000 in 2023 (Figure 3.15.8). A higher proportion of First Nations people were employed as pharmacists in Major cities (16.2 per 100,000 population) compared with Inner regional, Outer regional, Remote and very remote areas combined (8 per 100,000) (Table D3.15.10).

Figure 3.15.8: Employed First Nations pharmacists by remoteness area, 2016 to 2023

Source: Table D3.15.10. AIHW analysis of National Health Workforce Data Set; ABS population estimates and projections based on the 2021 Census (ABS 2024) for the calculation of rates.

Research and evaluation findings

One of the barriers to medication adherence is greater levels of poverty and social disadvantage among First Nations people (Davidson et al. 2010). A study demonstrated the positive impact of the CTG Co-payment program on medication usage and out-of-pocket expenses for First Nations people. The co-payment reductions were linked to a 39% relative increase in medication usage and a 61% decrease in out-of-pocket expenses. The increase in medication usage was particularly significant for non-concessional patients, with a 156% relative increase observed as a result of the CTG Co-payment program. In contrast, concessional patients experienced a 21% relative increase in medication usage. These results are measured per person, indicating a significant improvement in individual medication use among those who benefited from the largest co-payment reductions. These findings indicate that an approach of targeted co-payment reductions effectively enhanced access to prescription medications for First Nations people (Trivedi & Kelaher 2020).

A study of the effect of the CTG Co-payment Incentive investigated hospitalisations for chronic conditions among First Nations people, and found that there were downward trends in hospitalisation for chronic conditions, relative to other hospitalisations, in areas with higher levels of CTG script uptake (Trivedi et al. 2017).

The Independent Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation published in 2017 provided recommendations on future remuneration, regulation and other arrangements that apply to pharmacy and wholesalers for the dispensing of medicines and services offered under the PBS. The review aimed to ensure that there is continued reliable and affordable access to medicines listed on the PBS to Australians who need them, regardless of their location (King et al. 2017).

The review included recommendations to ensure access to PBS medicines and community pharmacy services for First Nations people (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b). These included improved access to medicines programs for First Nations people, particularly in rural areas; pharmacy ownership and operation by Aboriginal health services; and appropriate labelling of medicines for patients, including training for Aboriginal health services and pharmacies in remote areas to mitigate risks associated with remote and bulk supply (King et al. 2017).

Incarcerated First Nations people face significant systemic barriers to accessing health care, including PBS medication, within the prison system. For instance, a study showed many women reported unmet health needs in prison, facing medication discontinuation, abrupt reductions, and long wait times for assessments. Poor communication about new medications and diagnoses left them struggling post-release. Some women required hospital transfers due to acute symptoms and lacked follow-up care, worsening their mental health and leading to self-harm (Kendall et al. 2020).

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) published by the Australian Government's Department of Health and Aged Care in September 2024 aims to improve access to effective, safe, and affordable health technologies for Australians by evaluating and updating the current HTA policies and methods. The review includes 50 recommendations to enhance the systems and pathways for faster patient access to new medicines and vaccines through the PBS, particularly First Nations people. The key recommendations for First Nations people from the review include:

- First Nations Advisory Committee: Establish a committee to address priority health needs.

- Representation: Include First Nations representatives on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee.

- Submission Requirements: Require sponsors to consider the impact on First Nations health outcomes.

- Priority Areas: Develop criteria with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health services to identify high unmet clinical needs.

- Data Governance: Ensure privacy, data security, and First Nations data governance, aligning with existing strategies (e.g. the Department of Health and Aged Care’s Data Strategy 2022–2025).

The review emphasises system-wide reform to address inequities and improve access to innovative medicines for First Nations people (Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b).

A data linkage study examined the proportion of First Nations people who had ever received a script under the CTG PBS Co-payment Program between 2011 and 2020 across Australia. The study found that the uptake varied dramatically depending on where First Nations people live. In parts of northern Australia less than 30% of the First Nations population had ever received a CTG script. The factors influencing uptake of the scheme were: higher rates of chronic conditions in some rural and remote areas, particularly in New South Wales, South Australia, and Victoria; First Nations people in remote areas can receive free prescriptions through the Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services Program (RAAHS), reducing the perceived need for CTG scripts; issues with Indigenous status identification due to First Nations patients’ fear of poorer care; and small health practices with less administrative support and in more remote areas which are less likely to participate in the program. These factors contribute to the varying levels of program uptake and highlight the need for targeted strategies to improve access and participation (Saxby & Stephens 2024).

Evidence suggests that access to primary health care can be improved when services are tailored to needs or are owned and managed by First Nations communities. Central to efforts to build healthier communities is the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) sector. Its focus on prevention, early intervention and comprehensive care has reduced barriers to access and unintentional racism, progressively improving individual health outcomes for First Nations people. The sector also plays a significant role in training the medical workforce and employing First Nations people (Panaretto et al. 2014).

The Integrating Pharmacists within ACCHSs to Improve Chronic Disease Management (IPAC) study found that integrating pharmacists into the primary health care team within ACCHSs provided clinically and statistically significant improvements in self-reported adherence to medicines, the control of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors, glycaemic control in participants with type 2 diabetes, and reduced absolute CVD risk in First Nations adults with chronic disease. Pharmacists provided valuable medication reviews, education, and support, leading to improved medication adherence and safety and the presence of pharmacists within ACCHSs was well-received by both patients and healthcare providers, fostering a collaborative approach to healthcare. The study also found that the relationships between community pharmacies and ACCHSs were strengthened arising from the integrated pharmacist roles within ACCHSs. In 2023 the Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) considered the evidence from the IPAC study and supported public funding for integrating non-dispensing pharmacists within the primary health care teams of Aboriginal Health Services to improve chronic disease management (Couzos et al. 2020; Couzos et al. 2021; Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b; Smith et al. 2020).

The Indigenous Medication Review Service (IMeRSe) study, also funded as part of the 6th Community Pharmacy Agreement (CPA) Pharmacy Trial Program, focused on improving medication management for First Nations people. The study aimed to develop and assess a culturally responsive Indigenous Medication Review service and to improve clinical outcomes and to promote integrated multidisciplinary management of medication safety in primary care. The study was a partnership between the Pharmacy Guild of Australia, Griffith University, and the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO). The target population was First Nations people aged 18 and above with at least one chronic condition and at risk of medication-related problems (MRPs). Under this study community pharmacists integrated with local Aboriginal Health Services (AHSs) provided medication management services. Whereas the final report of the IMeRSe Feasibility Study claimed positive, clinically meaningful, outcomes for participants, MSAC considered the study at its March–April 2022 meeting and did not support public funding. MSAC considered the evidence presented did not demonstrate the comparative effectiveness and cost effectiveness of the proposed service with existing services. MSAC advised that there is an unmet need for culturally appropriate medication review services for First Nations people. Currently, no culturally responsive medication review service is available for First Nations Australians. Equitable access to quality health care, which is responsive to need and provides value for money, are key tenets of the National Medicines Policy (Department of Health and Aged Care 2022b).

Implications

First Nations people in Australia experience a burden of disease and injury 2.3 times as high as non-Indigenous Australians. Despite the average per person expenditure on pharmaceuticals for First Nations people being 1.4 times that of non-Indigenous Australians (age-adjusted, excluding s100 RAAHS), this spending is still insufficient to meet their significantly higher health needs.

The Australian Government's per person expenditure through the PBS is more equitably distributed, with around 1.6 times more per person for First Nations people compared to non-Indigenous Australians (after adjusting for age and excluding the s100 RAAHS). However, this expenditure still falls short of addressing the full extent of the health inequities. This unmet need underscores the crucial role of government funding in ensuring access to essential medicines for First Nations people. While there have been improvements in access to medicines and health outcomes, more effort is required to ensure First Nations people receive timely access to the medicines they require.

To provide effective health care to First Nations patients, the PBS Explanatory Notes recommend addressing several barriers: enhancing financial support to reduce medication costs; improving the availability and location of primary healthcare, specialists, and pharmacies, especially in rural and remote areas; providing resources to overcome language barriers; and improving the cultural competency of healthcare services to ensure First Nations patients feel respected and understood. Addressing these barriers is crucial to reducing health inequities and ensuring timely access to necessary medicines for First Nations people.

A key challenge for medication adherence among First Nations people is ineffective communication due to language barriers and experiences of racism in healthcare settings (Davidson et al. 2010). The findings from research underscore the critical need for culturally appropriate healthcare and improved access to medications for First Nations people. One study identifies cultural insensitivity and access issues as significant barriers to medication adherence, suggesting that enhancing cultural sensitivity and healthcare access can improve adherence rates. Another review highlights the importance of culturally appropriate interventions and the use of dose administration aids to support long-term medication adherence (Davidson et al. 2010; de Dassel et al. 2017; Kumble 2013).

Policy implications from these findings include the necessity of implementing culturally competent healthcare practices and ensuring that healthcare providers are trained in culturally appropriate care. Additionally, policies should focus on improving access to healthcare services and medications, particularly in remote and under-served areas. Specific policies should include expanding the Indigenous Dose Administration Aids (IDAA) Program, enhancing the CTG PBS Co-payment Program, increasing funding for community pharmacies, implementing medication management reviews, strengthening community health programs, and improving access to remote area health services. By addressing these barriers, medication adherence can be enhanced and would ultimately improve health outcomes for First Nations communities (Davidson et al. 2010; Northern Territory Government 2023).

The Pharmaceutical Society of Australia’s Guidelines for pharmacists supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with Medicines Management (the Guidelines) published in July 2022 provide comprehensive guidance on enhancing medicines management to improve health outcomes for First Nations people. The Guidelines outline the professional obligations of pharmacists to deliver culturally safe and responsive care, ensuring that First Nations patients receive respectful and effective support with their medications. The Guidelines emphasise the importance of understanding and respecting the cultural context of First Nations people, promoting health literacy, and fostering strong relationships between pharmacists and First Nations communities (Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd 2022).

For First Nations people living in remote areas without access to pharmacists or health services, the section 100 arrangements for RAAHS allow for the direct provision of PBS medicines during consultations, without charge or the need for a prescription form. This ensures timely access to essential medications and addresses the unique healthcare needs of these remote communities. This initiative complements the CTG Co-payment Program, which reduces the cost of PBS medicines, and the Community Service Obligation (CSO) funding, which ensures the availability of PBS medicines across Australia. Together, these programs enhance healthcare accessibility, affordability, and equity for First Nations people, promoting better health outcomes and reducing disparities.

While the mainstream Health Care Cards (HCCs) program provides eligible people access to subsidised PBS medicines and other government concessions, specific expenditure data comparing the CTG Co-payment Program with HCCs is not detailed in this measure. First Nations people with HCCs benefit from both the general subsidies available to all HCC holders and the additional support from the CTG program, assisting broader access to necessary healthcare services.

On 3 June 2024, the Australian Government signed the Eighth Community Pharmacy Agreement (8CPA) with the Pharmacy Guild of Australia. The 8CPA commenced on 1 July 2024 and includes $484.4 million to cover the costs of a one-year freeze on the maximum PBS co-payment for everyone with a Medicare card and a five-year freeze on the PBS co-payment for pensioners and other Commonwealth concession cardholders.

From 1 July 2024, the CTG PBS Co-payment Program was expanded to include section 100 PBS medicines when dispensed by a community pharmacy, approved medical practitioner or private hospital. This allows eligible CTG patients access to both section 85 (or ‘General Schedule’) and section 100 PBS medicines. This includes all section 100 PBS medicines supplied under Continued Dispensing arrangements. The program was further expanded from 1 January 2025 to all section 85 and section 100 PBS medicines being dispensed by public hospitals.

Section 100 medicines now included under the CTG PBS Co-payment Program encompass all medicines under the following Section 100 programs:

- Highly Specialised Drugs Program

- Efficient Funding of Chemotherapy Program

- Botulinum Toxin Program

- Growth Hormone Program

- In Vitro Fertilization (IVF) Program.

While significant strides have been made in improving access to essential medicines for First Nations people, persistent health inequities highlight the need for continued and enhanced policy efforts and health system improvements. Ensuring equitable access to healthcare services and medications requires sustained government commitment, targeted funding, and culturally competent care.

The Policy Context is at Policies and Strategies.

References

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2020. Australia’s health snapshots 2020. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

AIHW 2023. The health of people in Australia's prisons 2022. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

AIHW 2024a. Medicines in the health system. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed 6 May 2025.

-

AIHW 2024b. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme prescriptions over time. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

Australian Medical Association 2021. Important updates for Prescribers – Closing the Gap Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme Co payment Program Changes. Australian Medical Association. Viewed May 2025.

-

Couzos S, Smith D, Stephens M, Preston R, Hendrie D, Loller H et al. 2020. Integrating pharmacists into Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (IPAC project): Protocol for an interventional, non-randomised study to improve chronic disease outcomes. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 16:1431-41.

-

Couzos S, Smith D, Tremlett M, Loller H, Stephens M, Nugent A et al. 2021. Integrating Pharmacists within Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to Improve Chronic Disease Management (IPAC Project): Public Summary. Canberra: Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

-

Davidson PM, Abbott P, Davison J & DiGiacomo M 2010. Improving medication uptake in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Heart Lung and Circulation 19:372-7.

-

De Dassel JL, Ralph AP & Cass A 2017. A systematic review of adherence in Indigenous Australians: an opportunity to improve chronic condition management. BMC health services research 17:1-13.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2022a. National Medicines Policy Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. Canberra.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2022b. Improved medication management for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Feasibility Study (IMeRSe Feasibility Study). Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) Public Summary Document, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2023a. Sixth National Hepatitis C Strategy 2023-2030. Department of Health and Aged Care, Australian Government.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2023b. Integrating Pharmacists within Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to Improve Chronic Disease Management (IPAC Project). Canberra: Medical Services Advisory Committee (MSAC) Public Summary Document, Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024a. Closing the Gap (CTG) PBS Co-payment Program. Viewed 25/09/24.

-

Department of Health and Aged Care 2024b. Accelerating access to the best medicines for Australian now and into the future. Department of Health and Aged Care, Canberra.

-

Gall A, Stephens M, Gall Z, Armour D, Hewlett N, Kennedy M et al. 2025. First Peoples’ cultural medicines: A review of Australian health policies using an Indigenous critical discourse analysis approach. First Nations Health and Wellbeing - The Lowitja Journal 3.

-

Kendall S, Lighton S, Sherwood J, Baldry E & Sullivan EA 2020. Incarcerated Aboriginal women’s experiences of accessing healthcare and the limitations of the ‘equal treatment’ principle. International Journal for Equity in Health 19:48.

-

King S, Watson J & Scott B 2017. Review of Pharmacy Remuneration and Regulation–Final Report. (ed., Health Do). Canberra: Department of Health.

-

Kumble S 2013. Improving medication adherence amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Australian medical student. Journal. 2014 4:79–82.

-

Northern Territory Government 2023. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Specific Programs FACTSHEET Viewed 17/05/2025.

-

Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring IT 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical journal of Australia 200:649-52.

-

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia 2025. Closing the Gap emphasises need for pharmacists embedded in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Viewed 17/04/2025.

-

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia Ltd 2022. Guidelines for pharmacists supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples with Medicines Management.

-

Saxby K & Stephens M 2024. Medicare and Priority Populations: Structural and Place-based Considerations for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and LGBTIQ+ Australians. Australian Economic Review 57:149-59.

-

Smith D, Couzos S, Tremlett M, Loller H, Stephens M, Nugent A et al. 2020. Integrating practice pharmacists into Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services: Final report. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care.

-

Trivedi AN, Bailie R, Bailie J, Brown A & Kelaher M 2017. Hospitalizations for Chronic Conditions Among Indigenous Australians After Medication Copayment Reductions: the Closing the Gap Copayment Incentive. Journal of General Internal Medicine 32:501-7.

-

Trivedi AN & Kelaher M 2020. Copayment Incentive Increased Medication Use And Reduced Spending Among Indigenous Australians After 2010: A study of government-sponsored subsidies to reduce prescription drug copayments among indigenous Australians. Health Affairs 39:289-96.

-

WHO (World Health Organisation) 2004. WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines. Geneva: WHO.

-

WHO 2017. Towards access 2030: WHO essential medicines and health products strategic framework 2016-2030. World Health Organization.