Key messages

-

Transport is a key enabler for access to health care, goods and services and supports for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people to achieve education and employment. Lack of transport access can impede service access, even where distances are relatively short.

-

Based on 2021 Census data, about 9 in 10 First Nations households (88%) owned or used at least one motor vehicle, ranging from 66% in the Northern Territory to 93% in the Australian Capital Territory.

-

The proportion of First Nations households with one or more vehicle was higher in non-remote than remote areas (90% compared with 68%), and lower in the most socioeconomically disadvantaged areas (quintile 1) compared with those in the least disadvantaged areas (quintile 5) (80% compared with 96%).

-

In 2014–15, three-quarters (75% or 334,000) of First Nations people aged 15 and over reported they could easily get to places when they needed to, an increase from 70% (197,900) in 2002. However, in 2014–15, First Nations people aged 15 and over were 9.1 times as high as non-Indigenous Australians to report being unable to get to places they needed to or being housebound – 8.2% compared with 0.9%.

-

In 2018–19, 30% of First Nations people aged 15 and over reported they needed to go to a health provider in the last 12 months but could not. Of those, 13% reported transport/distance as the reason.

-

The rates of End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) among First Nations people in remote areas are very high; however, haemodialysis is often not available in these areas. Dialysis patients must therefore leave their Country and relocate to metropolitan or regional centres multiple times a week, disrupting their kinship and the cultural ties.

-

Many First Nations-specific primary health-care services offer transport for their clients to see health professionals. In 2022–23, transport accounted for 5.4% of client contacts (304,794) nationally.

-

All states and territories have established Patient Assisted Travel Schemes (PATS) to provide support for health-related travel and associated accommodation. A review of these PATS identified a number of issues, including inconsistent eligibility criteria between jurisdictions (particularly with regard to distance and eligible medical services), inconsistent benefits of the programs, and the complexity of the application process.

-

Weather conditions, particularly during the wet season, can be extremely disruptive to transport and service delivery in many remote parts of Australia. Damage or closure of roads can mean that communities are completely cut off from essential health services, food and fuel supplies, social activities, culture, and from each other, or that the cost of accessing these necessities increases dramatically.

-

While transport is a key enabler of access to health services, it also poses risks to health if the mode of transport is unsafe, such as if the vehicle is not in good working order, the driver is exhibiting risky driving behaviours, or the vehicle is overcrowded.

-

First Nations people are over-represented in transport-related morbidity and mortality. Over the period 2017–2021, there were 406 road deaths among First Nations people, accounting for 9.7% of all road deaths (4,165). After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the rate of road deaths among First Nations people was 2.9 times as high as among non-Indigenous Australians (12.0 compared with 4.2 per 100,000 population, respectively).

-

First Nations people experience barriers to obtaining a driver’s licence, including financial hardship; literacy and language issues; identification requirements; the need to practise driving which requires access to a car and access to an experienced driver, and being able to afford petrol; and cyclical defaults on traffic fines. A lack of driver licensing access for First Nations people is a key barrier to accessing health, education, and employment services. It can also result in increased contact with the criminal justice system, increased risk of transport-related injury and unsafe transport behaviours.

-

Evidence suggests that racialised people (characterised by their race) including First Nations people are subject to racial profiling, a higher level of high-discretion police vehicle, pedestrian and bicycle stops, as well as unjustified post-stop behaviour. Furthermore, around 35% of First Nations people were subjected to racism while using public transport.

-

The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) recommended in 2018 that state and territory governments should work with relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and community organisations to identify areas without services relevant to driver licensing and to provide those services, particularly in regional and remote communities.

Why is it important?

Transport is a key enabler for access to health care, goods and services, and supports Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people to achieve education and employment outcomes and meet cultural and kinship responsibilities (Cullen et al. 2017; Helps et al. 2010; Ivers et al. 2016).

A lack of access to transport is experienced disproportionately by women, children, disabled people, people from minority ethnic groups, older people and people with low socioeconomic status, especially those living in remote areas, including First Nations people (Macniven et al. 2016; Simcock et al. 2021). This lack of access faced by First Nations people has been identified as a critical barrier to accessing appropriate health care, along with logistics, distance and cost (see measure 3.14 Access to services compared with need). Having limited or no transport options significantly affects capacity to access specialist health care, including birthing services (Parker et al. 2014; Teng et al. 2014). This is particularly the case for patients with chronic health conditions (Teng et al. 2014), and those in rural and remote areas (AIHW 2019; Kelly et al. 2014). Access to transport is also a factor in enabling early detection and treatment of health conditions (see measure 3.04 Early detection and early treatment).

While transport is a key enabler of access to health services, it also poses risks to health if the mode of transport is unsafe, such as if the vehicle is not in good working order, the driver is exhibiting risky driving behaviours, or the vehicle is overcrowded (Fitts et al. 2013; Pammer et al. 2021; Symons et al. 2012). First Nations people are also over-represented in transport-related morbidity and mortality, such as road traffic crashes.

Transport accessibility, along with the prevalence of racial profiling during traffic stops, has also been observed to be a factor in the over-representation of First Nations people incarcerated for transport offences (Clapham et al. 2017). Contact with the criminal justice system is another social determinant of health (see measure 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system). This relationship is explored further in Research and evaluation findings.

Data findings

Access to transport

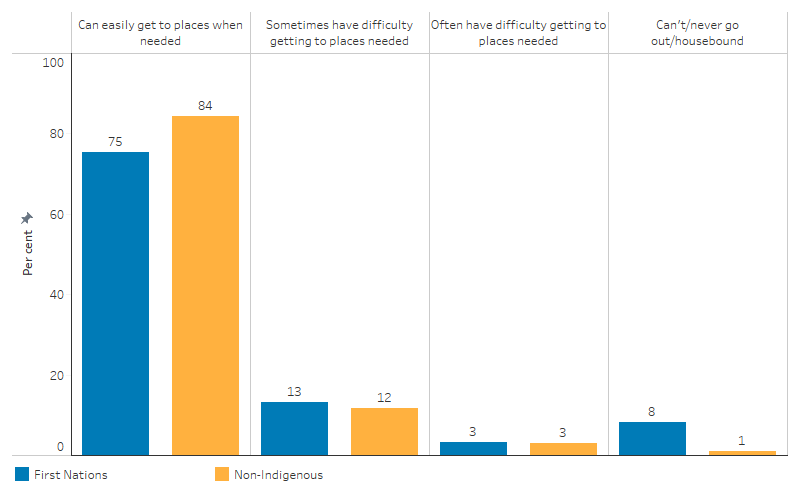

Based on self-reported data from the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS), about three-quarters (75% or 334,000) of First Nations people aged 15 and over could easily get to places when they needed to, an increase from about 70% (197,900) in 2002. For non-Indigenous Australians, data from the 2014 General Social Survey indicated that about 84% (15,335,700) could easily get to places they needed to (based on self-report), which was the same proportion that was reported in 2002 (Table D2.13.5, Figure 2.13.1).

Figure 2.13.1: Perceived ease/difficulty with transport, by Indigenous status, persons aged 15 and over, 2014–15

Source: Table D2.13.1. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15 and General Social Survey 2014.

The ease with which people get around differs by age group. For First Nations people aged 15–24, about 70% (96,000) reported that they could easily get to places they needed to. The proportion increased to about 79% (106,300) for those aged 45 and over (Table D2.13.1).

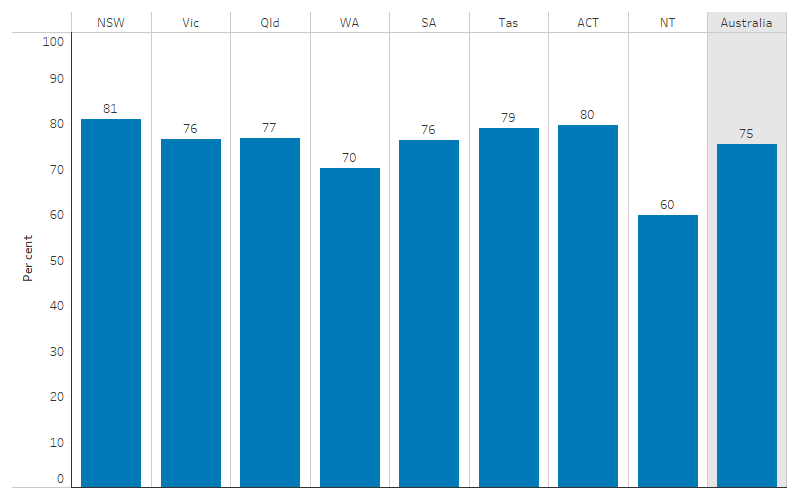

In 2014–15, the proportion of First Nations people aged 15 and over who reported easily being able to get to places they need to was highest in New South Wales (81% or 112,100) and lowest in the Northern Territory (60% or 27,700) (Table D2.13.4, Figure 2.13.2).

Figure 2.13.2: Proportion of First Nations people aged 15 and over who reported they were easily able to get to places when needed, by jurisdiction, 2014–15

Source: Table D2.13.4. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

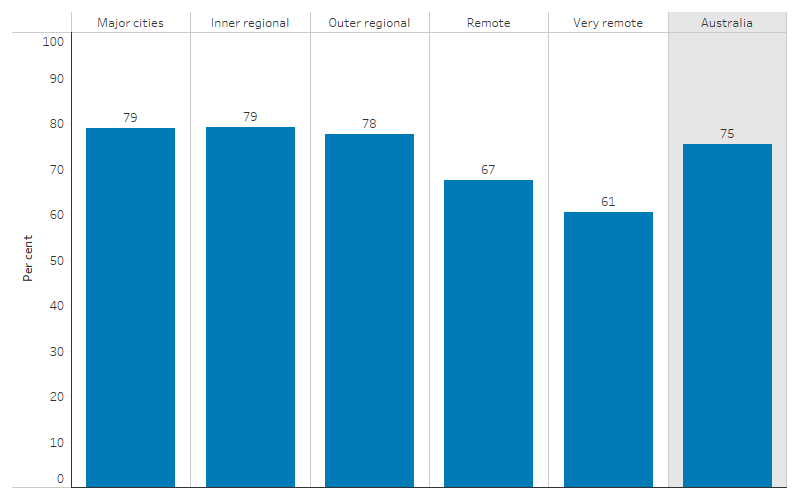

The proportion of First Nations people aged 15 and over who were able to easily get to places when needed was higher in non-remote areas than remote areas. In both Major cities and Inner regional areas, 79% of First Nations people reporting being able to get to places easily when needed, as could 78% in Outer regional areas. In comparison, 67% of First Nations people aged 15 and over in Remote areas were able to get to places easily when needed, decreasing to 61% in Very remote areas (Table D2.13.3, Figure 2.13.3).

Figure 2.13.3: Proportion of First Nations people aged 15 and over who reported they were easily able to get to places when needed, by remoteness, 2014–15

Source: Table D2.13.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

In 2014–15, First Nations people with high or very high levels of psychological distress were less likely than average to report easily being able to get places when needed (62%, compared with 75% of all First Nations people aged 15 and over), as were those with a disability or restrictive long-term health condition (70%), and those reporting fair or poor health (67%) (Table D2.13.6).

In 2014–15, First Nations people aged 15 and over were 9.1 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to report being unable to get to places they needed to, or never going out or being housebound – 8.2% (36,500) compared with 0.9% (170,900) (Table D2.13.1).

In the 2014–15 NATSISS, 29% (129,200) of First Nations people aged 15 and over reported having used public transport in the previous 2 weeks. Of those who had not used it, 33% (104,500) lived in an area in which there was no public transport available (Tables D2.13.9, D2.13.10). For First Nations people, the use of public transport was lower in remote areas (13% or 12,800) than in non-remote areas (34% or 116,200) (Table D2.13.9).

Based on self-reported data from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), 30% (243,700) of First Nations people aged 15 and over needed to go to a health provider in the last 12 months but did not. Of those who needed to go to a health service but did not, 13% reported transport/distance as the reason. This proportion was similar across service types: transport/distance was reported as a barrier for 12% of those needing to visit a hospital in the last 12 months but did not, 14% of those needing to visit a doctor, 10% of those needing to visit a dentist, 10% of those needing to visit a councillor, and 9% of those needing to visit other health services (see measure 3.14 Access to services compared with need) (Table D3.14.14).

Transport provided by First Nations-specific primary health care services

Many First Nations-specific primary health-care services provide transport services and take their clients to see health professionals, including health professionals who are not directly affiliated with the service. In 2022–23, there were 304,794 contacts for transport services (5.4% of client contacts nationally), with an average of 0.6 transport contacts per client. Across states and territories, the average number of transport contacts per client was highest in Western Australia and Tasmania (1.6 and 1.4 contacts per client, respectively). Across remoteness areas, the average number of transport contacts per client was highest in Remote areas (an average of 1.1 contacts per client in 2022-23), compared with 0.6 in both Inner regional and Outer regional areas, 0.4 in Very remote areas, and 0.3 in Major cities (AIHW 2024).

Household access to motor vehicles

Data on access to motor vehicles is available from the ABS 2014–15 NATSISS (with non-Indigenous comparisons from the 2014 General Social Survey), and the ABS Census of Population and Housing.

In the 2014–15 NATSISS, respondents aged 15 and over were asked if they could access a motor vehicle. Overall, three-quarters (75%) of First Nations people aged 15 and over reported having access to a motor vehicle (75% or 334,200) - consisting of an estimated 300,700 people (68% of all First Nations people aged 15 and over) who could access a motor vehicle whenever needed and a further 31,200 (7%) who could access a vehicle only in an emergency. First Nations people living in the Australian Capital Territory reported the highest rates of access to a vehicle (84% or 3,800) and those in the Northern Territory the lowest (66% or 30,700) (Table D2.13.8).

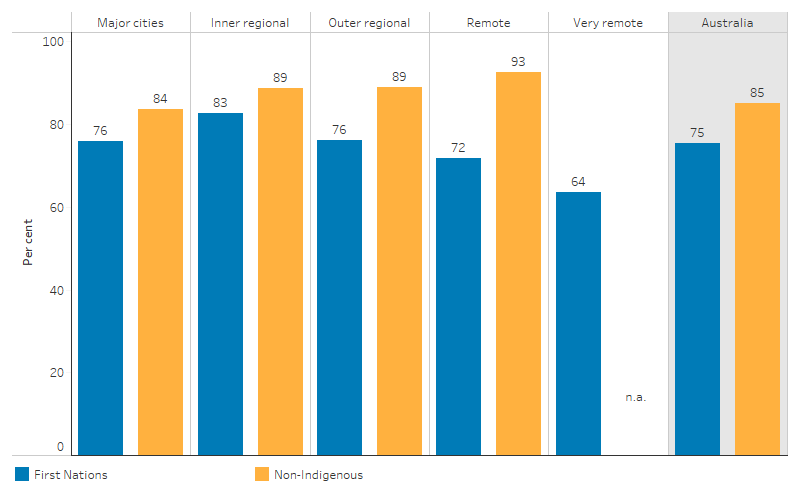

In 2014–15, access to motor vehicles among First Nations people was lower in remote than non-remote areas (67% in Remote and very remote areas combined, compared with 78% in non-remote areas combined). The proportion of First Nations people with access to a motor vehicle was 10 percentage points lower than the proportion of non-Indigenous Australians nationally (75% compared with 85%). The gap widened from an absolute difference of 6.1 percentage points in Inner regional areas (83% compared with 89%, respectively) to a difference of 21 percentage points in Remote areas (72% compared with 93%, respectively) (Table D2.13.7, Figure 2.13.4).

Figure 2.13.4: Proportion of persons aged 15 and over with access to a motor vehicle, by remoteness and Indigenous status, 2014–15

Source: Table D2.13.7. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15 and General Social Survey 2014.

In the Census of Population and Housing, information was collected on the number of registered motor vehicles owned or used by household members that were garaged or parked at or near private dwellings on Census night. In these data, a First Nations household is defined as an occupied private dwelling where at least one of its usual residents identifies as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. The remaining households are called ‘other households’.

In 2021, of around 342,600 First Nations households, 88% owned or used at least one vehicle, while 12% did not have a motor vehicle (excludes households where the number of vehicles was not reported). About one-third of First Nations households (32%) had one vehicle, 34% had 2 vehicles, and the remaining 22% of households had 3 or more vehicles. The proportion of First Nations households without a vehicle was higher than for other households (12% compared with 7.2%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023).

About 9 in 10 First Nations households owned or used a motor vehicle in all jurisdictions except the Northern Territory, with the proportion ranging between 85% (in both Western Australia and South Australia) and 93% (Australian Capital Territory). In contrast, two-thirds (66%) of First Nations households in the Northern Territory had one or more vehicles (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023).

In 2021, the proportion of First Nations households with one or more vehicles was higher in non-remote areas (90%) than in remote areas (68%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023).

The Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (IRSD) categorises areas into quintiles based on the socioeconomic status of people living in that the area (see measure 2.09 Socioeconomic indexes). Quintile 1 represents the most disadvantaged 20% of areas, while quintile 5 represents the least disadvantaged 20%. In 2021, the proportion of First Nations households without a motor vehicle was 20% for households living in the most disadvantaged 20% of areas, compared with 4.4% among households in the least disadvantaged 20% of areas. The proportion of First Nations households owning one or more vehicles was higher in the least disadvantaged 20% of areas (96%) compared with the most disadvantaged 20% (80%). Additionally, First Nations households living in the least disadvantaged 20% of areas were more likely to have 3 or more vehicles (31%), compared with those in the most disadvantaged areas (15%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023).

In 2021, there was a lower average number of vehicles per person in First Nations households than in other households. There was an average of 0.85 vehicles per person for First Nations households with at least one person aged 17 and over, compared with 0.92 vehicles per person for other households (Table D2.13.11).

Method of travel to work

In the 2021 Census of Population and Housing, employed people aged 15 and over were asked to record up to three methods of travel they used to get to work on the day of the Census, 10 August 2021. Caution is needed when interpreting data on how people got to work, because the 2021 Census was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Around the time of the Census, some states like New South Wales and Victoria had COVID-19 restrictions in place that limited people's ability to go to their workplace. Data for areas that did not have stay-at-home orders or any restrictions, before and during the Census, might also have been affected by social change toward more flexible work options and a reluctance to come into contact with others.

In 2021, vehicle use was the most common method of travel to work for First Nations people. Among First Nations people aged 15 and over who were employed:

- about two-thirds (67%) of First Nations employed people aged 15 and over in 2021 used a vehicle such as car, truck, motorbike, or scooter to get to work, compared with 58% of non-Indigenous Australians

- 5.0% used active transport (bicycle (0.5%) or walk (4.5%))

- 4.3% used public transport (bus (2.2%), train (1.5%), and ferry, tram, light rail, taxi, ride-share service combined (0.7%)) to get to work

- 23% either worked at home (10.1%) or did not go to work (12.6%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2022).

Road deaths

This section presents data on road deaths based on the ABS Causes of Death Collection, as published by the Department of Infrastructure Transport Regional Development Communications and the Arts.

Data are reported for the 5 jurisdictions in which the quality of Indigenous status in deaths data is considered adequate for reporting (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory). Data are combined over a five-year period (2017 to 2021).

Over the period 2017–2021, there were 406 road deaths among First Nations people – 9.7% of all road deaths (4,165). About two-thirds of the road deaths were in passenger vehicles (277, 68.2%), and 9.9% were riding or passengers on a motorcycle. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the rate of road deaths among First Nations people was 2.9 times as high as among non-Indigenous Australians (12.0 compared with 4.2 per 100,000 population, respectively).

Over the period 2017–2021, 71% of road deaths among First Nations people were males (287 of 406). Across age groups, the highest rate for both males and females was among those aged 26–39 (29.7 deaths per 100,000 population for males, and 13.5 deaths per 100,000 population for females).

Across 5 states and territories, the age-standardised rates for road deaths among First Nations people ranged from 7.8 per 100,000 population in New South Wales to 21.8 per 100,000 population in the Northern Territory over the 2017–2021 period.

Over the period 2017–2021, the road death rates among First Nations people were higher in more remote areas. The age-standardised road death rates among First Nations people ranged from 6.2 per 100,000 population in Major cities to 26.2 per 100,000 population in Very remote areas (Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts 2023).

Research and evaluation findings

Key factors contributing to the increased rate of road injury and death for First Nations people are largely systemic, and include the safety of vehicles, safety of roads and roadsides, safety of road use and speed. The safety of a vehicle can refer to the state of the vehicle itself, as well as the conditions inside the vehicle, including overcrowding. Unsafe roads and roadsides could include unsealed roads, or under-maintained roads in rural and remote areas, which are associated with higher crash rates. Safe road use involves wearing a seatbelt, having a driving license and adequate driving training, and not being influenced by alcohol or fatigue. A broad review of road safety programs across Australia found that many jurisdictions had programs for road safety education and driver licensing, but comparatively few programs for fitting child restraints or for addressing public transport issues. There is limited data available to facilitate effective evaluations of the outcomes of these programs (Brameld & Meuleners 2018).

The literature provides information on the barriers to accessing health services faced by First Nations people living in urban and regional communities. These barriers can be categorised as obstacles of availability (including physical accessibility such as lack of transport); affordability, appropriateness and cultural acceptability (Ware 2013).

Research has found that 35% of Indigenous Australians were subjected to racism while using public transport (Ferdinand et al. 2012). This, along with the availability of public transport, impedes access to services. There is also evidence that police in Australia engage in some degree of racial profiling. Racialised people (characterised by their race) in Australia, including First Nations people, are subject to a higher level of high-discretion police vehicle, pedestrian and bicycle stops, as well as unjustified post-stop behaviour (Hopkins & Popovic 2024).

The imposition of fines and fine enforcement regimes for traffic offences affect First Nations people disproportionately. Fine enforcement regimes can operate to further entrench disadvantage and the criminalisation of disadvantaged groups, especially when the penalty for default or secondary offending includes further fines, driver licence suspension or disqualification, and imprisonment (Anthony et al. 2023; Australian Law Reform Commission 2018; Clapham et al. 2017; Masterton et al. 2023).

A review of the relationship between transport and disadvantage in Australia showed how transport and disadvantage intersect and why some groups are especially vulnerable to transport disadvantage, including First Nations people. The review highlighted that transport options for First Nations people in remote communities and communities located in fringe urban areas are limited. It also showed that a significant proportion of First Nations people living in remote areas have no access to public transport and one-third have no access to a car. It noted that for those cars that are available in remote First Nations communities, they are heavily used, and because they are often purchased second hand and used in rough terrain, maintenance is expensive, and they often have a short lifespan. The review also found that similarly, in non-remote locations, car access may be a concern for First Nations people who typically have much lower access rates than non-Indigenous Australians. Furthermore, in non-remote areas, 18% reported having no public transport and 2% were unable to reach places when needed (ABS 2010; Rosier & McDonald 2011).

Many First Nations people live in remote areas where they strive to maintain their communities and cultural traditions. Consequently, health services and other infrastructure can be limited, and they face significant transport and access challenges. The quality of road infrastructure can be one such barrier; 42% of respondents in a study of 3 very remote communities reported experiencing serious difficulties when travelling due to poor road conditions. Unsealed roads are often closed several times a year due to weather events, and in some northern areas can be closed for months at a time in the wet season. Unsealed roads can have direct health effects, contributing to dust nuisance, which can cause eye conditions, skin disorders and respiratory infections (Bailie et al. 2002). Road conditions also have an effect on the severity of car crashes; driving on unsealed roads or during the wet season were both associated with a higher rate of fatality in the event of a crash (Dempsey 2016).

Weather conditions, particularly during the wet season, can be extremely disruptive to transport and service delivery in many remote parts of Australia. Damage or closure of roads can mean that communities are completely cut off from essential health services, food and fuel supplies, social activities, culture, and from each other, or that the cost of accessing these necessities increases dramatically (Parliament of Australia 2023a). There have been instances of hospitals (in Townsville and Mount Isa) struggling initially to transport patients to the hospital for treatment, but also being placed under additional pressure when it was not possible for these patients to safely leave due to weather conditions (Memmott et al. 2006).

The challenges associated with transport also impact access to employment. One study found that the likelihood of employment reduced with distance from town centres (measured in the study as distance from Alice Springs), noting that the effect of distance was really the effect of the increased cost of travel. Sealed roads and other infrastructure upgrades are therefore thought to have a positive impact on access to jobs, by reducing the cost of commuting (Dockery & Hampton 2015).

In remote areas, many patients requiring regular dialysis treatment must relocate to where treatment is accessible. The South Australian Mobile Dialysis Truck facilitates patients who have relocated to return to their community for short periods while continuing treatment. A qualitative evaluation of the dialysis truck explored the impact on the health and wellbeing of First Nations dialysis patients, and the facilitators and barriers to using the service.

-

The rates of End-Stage Kidney Disease (ESKD) among First Nations people in remote areas are very high; however, haemodialysis is often not available in these areas. Dialysis patients must therefore leave their Country (with its traditions and supports) and relocate to metropolitan or regional centres (for dialysis 3 times per week), disrupting their kinship and the cultural ties that are important for their wellbeing. The South Australian Mobile Dialysis Truck is a service that visits remote communities for 1-to-2-week periods, allowing patients to return to Country while continuing treatment. This reunites patients with their friends and family and provides a chance to take part in cultural activities.

-

The evaluation illustrated how a mobile health delivery strategy can improve the social and emotional wellbeing of First Nations ESKD patients who have had to relocate for dialysis and build positive relationships and trust between metropolitan nurses and remote patients. This trust fostered improved engagement with associated health services, which has significant clinical implications. The dialysis truck was consistently reported as having a positive impact on patients, providing them with an opportunity to return home to participate in Country and culture and spend time with family, and alleviating the pain and grief from separation and displacement. The dialysis truck was also shown to be beneficial to non-Indigenous nurses in terms of cultural knowledge and competency, including learning from their patients.

-

Recommendations arising from the evaluation were directed at modifying barriers noted by staff and patients towards the success of trips by the dialysis truck. This includes the arrangement of appropriate transport and accommodation for patients that need it.

-

The evaluation noted that potential areas for future research could include collecting data from patients who had not been on trips, to elicit their experiences and compare data on quality of life. Quantitative data could also be sought on hospital admissions and Royal Flying Doctor Service retrievals, as the evaluation suggested that these are reduced in the presence of the dialysis truck (Conway et al. 2018).

All states and territories have established Patient Assisted Travel Schemes (PATS) to provide support for travel and associated accommodation. A review of these PATS identified a number of issues, including inconsistent eligibility criteria between jurisdictions (particularly with regard to distance and eligible medical services), inconsistent benefits of the programs, and the complexity of the application process (Bachman et al. 2017).

One study of three First Nations communities reported patient transport assistance options provided by non-government organisations included specific bus services for enabling access to health care, as well as ad hoc transport provided by health-care service staff. However, the timing and flexibility of bus services was an issue, and relying on health-care workers was described as impractical, unsustainable and time consuming for staff (Nolan-Isles et al. 2021).

Having access to reliable transport is particularly important in an emergency, or when one is under stress. This could include travelling to a hospital for your own or others’ treatment, or travelling for an urgent cultural or family matter. Travelling in an emergency exacerbates unsafe travel behaviours, and can lead to a cycle of repeated crises without the appropriate support (Helps et al. 2008).

Driver licensing – impact on health and social determinants

Studies have shown an endemic lack of licensing access for First Nations people related to financial hardship, unmet cultural needs and an inequitable system, resulting in a barrier to social inclusion that First Nations people frequently encounter (Cullen et al. 2016b). Driving without a license for First Nations people has also been linked to increased risk of transport-related injury and unsafe transport behaviours (Clapham et al. 2017). In 20–40% of fatal First Nations crashes, the driver is unlicensed, a significantly higher number compared with non-Indigenous Australians (Infrastructure and Transport Ministers 2021). Increased driver licensing leads to less overcrowding in vehicles, higher rates of seatbelt usage and generally safer driving behaviours (Brameld & Meuleners 2018).

Barriers to driver licensing participation are systemic and include financial cost, literacy and language issues, lack of confidence, proof of identity documents (many First Nations people do not have a birth certificate), difficulty meeting requirements of graduated driver licensing, service provision, and the justice system. The relationship with the justice system is two-way – while previous contact with the justice system can be a barrier to accessing a license, a lack of access to a license can also lead to further contact with the criminal justice system. For example, difficulty in obtaining a license, combined with the necessity to drive to access services (including education, employment, and health) can result in higher amounts of unlicensed driving. This unlicensed driving results in fines, imprisonment or license disqualification, all of which make it harder to obtain a license (Barter 2015; Cullen et al. 2017).

An evaluation of the DriveSafe Northern Territory remote driver-licensing program found that while public transportation may compensate for the lack of private transport in non-remote areas, a higher proportion of First Nations people in both remote and non-remote areas have less access to a motor vehicle compared with non-Indigenous Australians. First Nations people also experience barriers to obtaining a driver’s licence, including financial hardship; literacy and language issues; identification requirements; the need to practise driving which requires access to a car and access to an experienced driver, and being able to afford petrol; and cyclical defaults on traffic fines (Cullen et al. 2016a).

A survey of participants in the Driving Change program in New South Wales found that participants who obtained an independent license were more likely to report a new job or change in job than those who did not attain a license; with those from regional areas more likely to gain an independent license than those from urban areas (Porykali et al. 2021a).

A broader review of driver licensing programs across the country found that while driver licensing programs appeared to be effective in improving licensing rates for First Nations people, most were not robustly evaluated, and there was little to no evidence around the effect of these programs on employment (Porykali et al. 2021b).

Implications

Patient transport assistance designed to help patients in accessing health care on a regular basis is an important aspect of health service delivery. This is particularly the case for many First Nations households in which private and public transport options can be restricted. Patient transport assistance is provided by voluntary groups, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs), hospitals and ambulance services. The need for these services can present difficulties for ACCHOs, as there is often no specific funding for providing transport services, and this expenditure must come out of regular operating funding (South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute 2020). Further research is required into the effectiveness and efficiency of this transport assistance.

Other approaches to providing medical care have also been adopted to alleviate poor access to health care as a result of distance and lack of transport, such as support for specialist services flying into remote localities. In one study, it was noted that this approach provided limited opportunity for the development of relationships between patients and health-care workers, but that this could be addressed by having the same health-care worker return to the community over an extended period (Nolan-Isles et al. 2021).

The higher rate of road deaths for First Nations people can be largely attributed to driver licensing and infrastructure issues, particularly in remote areas. The Australian Law Reform Commission (ALRC) recommended in 2018 that state and territory governments should work with relevant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations and community organisations to identify areas without services relevant to driver licensing and to provide those services, particularly in regional and remote communities (Australian Law Reform Commission 2018). A number of jurisdictions have programs in place to provide culturally appropriate support for First Nations people to access driver licensing, including the Driver Licensing Access Program in New South Wales, the Indigenous Driver Licensing Program in Queensland and the Aboriginal Road Safety and Driving Licensing Program in South Australia.

In June 2024, the New South Wales government launched the Kangaroo Service, a mobile service centre providing access to government services and transactions to remote communities, including driver license and vehicle registration renewals, driver testing, and provision and renewal of proof of identity documents.

More research is required into the various barriers to accessing appropriate health care including the reliability of transport options. This will hopefully lead to further understanding of how this challenge has a broader influence on the social and economic circumstances of both health service users who need to travel significant distances while unwell, and on carers who support attendance at services for antenatal care, young children, people with a disability, or people suffering from chronic health conditions, mental health or substance use issues (Lee et al. 2014).

Culturally secure transport can help First Nations people in accessing health services that are far from home. Additionally, services provided closer to home, in possibly non-standard settings or providing some services through home visitation, can also improve access (Ware 2013).

Although research and practice wisdom can suggest strategies to improve access to health care, including transport options, individual service providers need to consider what will best meet the needs of their clients. Community and client engagement is needed to understand what barriers clients face in accessing health care so these can be addressed at the local level (Ware 2013).

More research is required into the complex relationship between transport and disadvantage in Australia, including the relationship between transport difficulty and social disadvantage of First Nations people (Rosier & McDonald 2011).

Hospitalisation and deaths due to injuries from transport accidents also remain a concern (see measure 1.03 Injury and poisoning).

The Policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2010. The health and welfare of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples 2010. Canberra.

-

ABS 2022. 2021 Census - counting persons, place of usual residence [Census TableBuilder].

-

ABS 2023. 2021 Census - counting dwellings, place of enumeration [Census TableBuilder].

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Rural and remote health Cat. no. PHE 255. Web report, 29 May 2017. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Viewed 17 October 2020 2019.

-

AIHW 2024. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: results from the OSR and nKPI collections. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

Anthony T, Sherwood J, Blagg H & Tranter K 2023. Neo-Colonial Interventions – Regulating First Nations Peoples' Motor Vehicles and Criminalising Drivers. In. Unsettling Colonial Automobilities. Emerald Publishing Limited, 29-42.

-

Australian Law Reform Commission 2018. Pathways to justice–An inquiry into the incarceration rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

-

Bachman S, Ferguson D, Gilritchie E, Heggart M, Irwin R, Longordo F et al. 2017. Patient Assisted Travel Schemes: are they actually assisting rural Australians? Cairn, Qld.

-

Bailie R, Siciliano F, Dane G, Bevan L, Paradies Y & Carson B 2002. Atlas of health-related infrastructure in discrete Indigenous communities. Deakin University.

-

Barter A 2015. Indigenous driving issues in the Pilbara Region. Proof of Birth:62-72.

-

Brameld K & Meuleners L 2018. Aboriginal Road Safety: A review of issues, initiatives and needs in Western Australia: Phase 1. Curtin-Monash Accident Research Centre.

-

Clapham K, Hunter K, Cullen P, Helps Y, Senserrick T, Byrne J et al. 2017. Addressing the barriers to driver licensing for Aboriginal people in New South Wales and South Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 41:280-6.

-

Conway J, Lawn S, Crail S & McDonald S 2018. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the Country Health SA Dialysis bus. BMC Health Services Research 18:1010.

-

Cullen P, Chevalier A, Byrne J, Hunter K, Gadsde T & Ivers R 2016a. ‘It’s exactly what we needed’: A process evaluation of the DriveSafe NT Remote driver licensing program. Canberra, Australia.

- Cullen P, Clapham K, Hunter K, Treacy R & Ivers R 2016b. Challenges to driver licensing participation for Aboriginal people in Australia: a systematic review of the literature. International Journal for Equity in Health 15:134.

- Cullen P, Clapham K, Hunter K, Porykali B & Ivers R 2017. Driver licensing and health: A social ecological exploration of the impact of licence participation in Australian Aboriginal communities. 6:228-36.

-

Dempsey KEM 2016. In harm's way: a study of Northern Territory linked crash records. Doctorate. Charles Darwin University.

-

Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts 2023. First Nations Peoples road deaths excel tables.

-

Dockery AM & Hampton K 2015. The dynamics of services, housing, jobs and mobility in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities in central Australia. Ninti One Limited.

-

Ferdinand A, Paradies Y & Kelaher M 2012. Mental Health Impacts of Racial Discrimination in Victorian Aboriginal Communities: The Localities Embracing and Accepting Diversity (LEAD) Experiences of Racism Survey. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute.

-

Fitts MS, Palk GR & Jacups SP 2013. Alcohol restrictions and drink driving in remote Indigenous communities in Queensland, Australia. Montreal, Canada.

-

Helps Y, Moodie D & Warman G 2010. Aboriginal People Travelling Well: Community Report. Melbourne: The Lowitja Institute.

-

Helps Y, Moller J, Kowanko I, Harrison JE, O’Donnell K & de Crespigny C 2008. Aboriginal people travelling well: issues of safety, transport and health. Department of Infrastructure and Transport, Australian Government.

-

Hopkins T & Popovic G 2024. Do Australian police engage in racial profiling? A method for identifying racial profiling in the absence of police data. Current Issues in Criminal Justice:1-22.

-

Infrastructure and Transport Ministers 2021. Fact sheet: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander road safety, National Road Safety Strategy 2021-2030. (ed., Department of Infrastructure T, Regional Development and Communications). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia 2021.

-

Ivers RQ, Hunter K, Clapham K, Helps Y, Senserrick T, Byrne J et al. 2016. Driver licensing: descriptive epidemiology of a social determinant of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40:377-82.

-

Kelly J, Dwyer J, Willis E & Pekarsky B 2014. Travelling to the city for hospital care: access factors in country Aboriginal patient journeys. Australian Journal of Rural Health 22:109-13.

-

Lee KS, Harrison K, Mills K & Conigrave KM 2014. Needs of Aboriginal Australian women with comorbid mental and alcohol and other drug use disorders. Drug & Alcohol Review 33:473-81.

-

Macniven R, Richards J, Gubhaju L, Joshy G, Bauman A, Banks E et al. 2016. Physical activity, healthy lifestyle behaviors, neighborhood environment characteristics and social support among Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal adults. Prev Med Rep 3:203-10.

-

Masterton G, Brady M, Watson-Brown N, Senserrick T & Tranter K 2023. Driver licences, diversionary programs and transport justice for first nations peoples in Australia. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 12:93-107.

-

Memmott P, Long S & Thomson L 2006. Mobility of Aboriginal people in rural and remote Australia. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

-

Nolan-Isles D, Macniven R, Hunter K, Gwynn J, Lincoln M, Moir R et al. 2021. Enablers and Barriers to Accessing Healthcare Services for Aboriginal People in New South Wales, Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18.

-

Pammer K, Freire M, Gauld C & Towney N 2021. Keeping Safe on Australian Roads: Overview of Key Determinants of Risky Driving, Passenger Injury, and Fatalities for Indigenous Populations. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18.

-

Parker S, McKinnon L & Kruske S 2014. 'Choice, culture and confidence': key findings from the 2012 having a baby in Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander survey. BMC Health Services Research 14:196.

-

Parliament of Australia 2023. Inquiry into the implications of severe weather events on the national regional, rural, and remote road network. Canberra, Australia.

-

Porykali, Cullen P, Hunter K, Rogers K, Kang M, Young N et al. 2021a. The road beyond licensing: the impact of a driver licensing support program on employment outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 21:2146.

-

Porykali, Hunter K, Davies A, Young N, Sullivan E & Ivers R 2021b. The effectiveness and impact of driver licensing programs on licensing and employment rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia: A systematic review. 21:101079.

-

Rosier K & McDonald M 2011. The relationship between transport and disadvantage in Australia. Communities and Families Clearinghouse Australia Resource sheet.

-

Simcock N, Jenkins KEH, Lacey-Barnacle M, Martiskainen M, Mattioli G & Hopkins D 2021. Identifying double energy vulnerability: A systematic and narrative review of groups at-risk of energy and transport poverty in the global north. 82:102351.

- South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute 2020. The Centre of Research Excellence in Aboriginal Chronic Disease Knowledge Translation and Exchange (CREATE) report, Chapter 7 Approaches to Funding in newly established ACCHOs, Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations in practice: Sharing ways of working from the ACCHO sector. Wardliparingga Aboriginal Health Equity Theme. Adelaide, South Australia: The University of Adelaide.

- Symons M, Gray D, Chikritzhs T, Skov SJ, Saggers S, Boffa J et al. 2012. A longitudinal study of influences on alcohol consumption and related harm in Central Australia: With a particular emphasis on the role of price. Perth: NDRI.

-

Teng THK, Katzenellenbogen JM, Hung J, Knuiman M, Sanfilippo FM, Geelhoed E et al. 2014. Rural–urban differentials in 30-day and 1-year mortality following first-ever heart failure hospitalisation in Western Australia: a population-based study using data linkage. BMJ Open 4:e004724.

-

Ware VA 2013. Improving the accessibility of health services in urban and regional settings for Indigenous people. (ed., Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.