Key messages

- In 2022–23, the total health expenditure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people was estimated to be $12,286 million. Of this, 55% was spent on hospital services, 7% on Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services and other First Nations-specific health programs under the Australian Government’s Indigenous Australians' Health Programme (IAHP), 6% on Medicare services, and 5.6% on PBS medicines. The remaining 27% was spent on other recurrent health expenditure, with a large part of this spent on Community health services (excluding IAHP).

- From 2016–17 to 2022–23, total health expenditure per person for First Nations people increased by 4.3% per annum after adjusting for inflation, from $9,447 per person to $12,146. Australian Government per person expenditure increased by 2.4% per annum over this period and state/territory government expenditure increased by 7.8%.

- Per person expenditure by the Australian Government on First Nations-specific health programs increased from $1,110 per person in 2016–17 to $1,144 per person in 2022–23 after adjusting for inflation, an average increase of 0.5% per annum.

- In 2022–23, per person MBS expenditure for First Nations people was around two-thirds (ratio of 0.65) the expenditure for non-Indigenous Australians ($729 and $1,117 per person, respectively). After adjusting for differences in the age-structure between the two populations, MBS expenditure for First Nations people was 0.9 times that of non-Indigenous Australians.

- In 2022–23, for First Nations people, expenditure for primary health care services was $4,176 per person, compared with $3,080 per person for non-Indigenous Australians, at a ratio of 1.4. Expenditure for secondary/tertiary health services (mainly hospital services) was $7,969 per person for First Nations people, compared with $5,822 for non-Indigenous Australians (at a ratio of 1.4).

- For public hospital services, per person expenditure for First Nations people was 2.0 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians ($6,306 per person compared with $3,079 per person). However, when calculated as a cost per hospitalisation, rather than amount per person, expenditure on public hospital services was lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians ($7,555 and $8,936 per hospitalisation respectively).

- In 2022–23, expenditure on potentially preventable hospitalisations was $646 per person for First Nations people, compared with $249 per person for non-Indigenous Australians. The difference in expenditure for potentially preventable hospitalisations due to chronic conditions was $155 per person, with a difference of $148 per person due to acute conditions, and $119 per person due to vaccine preventable conditions.

- The Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing’s Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP) Economic Evaluation Phase One found that higher attendance at Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) reduced the likelihood of hospital admission, as well as providing health gains.

- National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), in partnership with Equity Economics, undertook an analysis of the gap in health expenditure for First Nations people. This report concluded that there remains a large and persistent gap in expenditure on health care for First Nations people given the additional need.

- Investing $1 in primary care in remote First Nations communities was found to save $3.95–$11.75 in hospital costs, in addition to benefits for individual patients. High levels of primary care utilisation were associated with decreases in avoidable hospitalisations, deaths and years of life lost.

Why is it important?

A basic principle of health equity is that everyone should have an equal opportunity to be healthy, which requires that the distribution of health resources reflects the differing levels of need among population groups. Inequities in health arise when differences in health status are avoidable and unfair, often stemming from inadequate access to essential health services, exposure to unhealthy living conditions, and social and economic disadvantage. These inequities are exacerbated by a lack of proportionate resource allocation, particularly for disadvantaged populations (Braveman & Gruskin 2003; Whitehead 1991; World Health Organization 2025).

The most recent data from the Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS) showed that in 2018, the age-standardised total burden of disease for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people was 2.3 times that for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022). Aligning health expenditure with the disproportionate health burden faced by First Nations people is essential to provide fair opportunities for all individuals to attain their full health potential. A broad assessment of how well this principle is implemented is provided by comparing differentials in health status with differences in per capita health expenditure.

Health expenditure is defined as spending on health goods and services by all levels of governments as well as non-government entities such as individuals, private health insurers, and injury compensation insurers, which includes hospitals (both public and private); primary health care (unreferred medical services, dental services, other health practitioners, community health, public health, and medications); referred medical services; other services (patient transport services, aids and appliances, and administration); research; and capital expenditure (AIHW 2024a).

The objective of the health care system is to meet the health care needs of the Australian population and produce positive health outcomes not only for individual Australians but also for the population as a whole. Expenditure is one measure of the needs met. It does not tell us about the unmet need (gaps) or the quality, appropriateness, cultural safety or responsiveness of care.

Four interacting factors within Australia’s health system potentially have major consequences for the health of many First Nations people, namely limited First Nations-specific primary health care services; First Nations peoples’ lack of access to mainstream health services and limited access to government health subsidies; increasing price signals in the public health system (such as co-payments) and a low uptake of private health insurance; and an inability to sustain and increase real expenditure levels over time to ensure it is commensurate with the more complex health needs of First Nations people (Alford 2015).

Data findings

This measure presents information on health expenditure for First Nations people.

The AIHW Health Expenditure Database does not include direct information on health expenditure by Indigenous status. The share of expenditure that is attributable to First Nations people therefore needs to be estimated. The estimate used depends on the specific source of funds and the areas of expenditures being considered. Estimates are based on about 10 different datasets, including the Health Expenditure Database, Disease Expenditure Database, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) data, Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) data, weighted Voluntary Indigenous Identifier (VII) data, expenditure data provided by states and territories, population data, and others.

Data presented in this measure are recurrent expenditures and do not include capital expenditures.

Total health expenditure

In 2022–23, total health expenditure for First Nations people was estimated to be $12,286 million (including government and non-government expenditure), contributing to about 5.2% of national health expenditure (Table D3.21.1). Of this:

- over half (55%, $6,717 million) was spent on hospital services

- 7% ($861 million) was spent on Australian Government First Nations-specific health programs through the Australian Government Indigenous Australians' Health Programme (IAHP)

- 6% ($737 million) was spent on Medicare services through the Medicare Benefits Schedule

- 5.6% ($685 million) was spent on benefit-paid pharmaceuticals through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (see also measure 3.15 Access to prescription medicines).

- the remaining 27% ($3,286 million) was spent on other recurrent health expenditure

– The majority of this expenditure was on community health services (excluding ACCHSs and other services funded under the IAHP) ($816 million), other medications ($576 million) and dental services ($482 million) (Table D3.21.1).

Australian governments funded about 87% of health expenditure for First Nations people in 2022–23 (40% state and territory, and 47% Australian Government). The remaining 13% ($1,625 million) was funded by non-government sources (Table D3.21.2).

The average health expenditure per person for First Nations people in 2022–23 was $12,146. Of this, $6,306 per person was for public hospital services (admitted and non-admitted patient services), $334 per person for private hospital services (admitted patient services only), $851 per person for Australian Government First Nations-specific health programs, $729 per person for MBS services, $677 per person for PBS pharmaceuticals and $3,249 per person for other recurrent health expenditure (Table D3.21.1) (see Box 3.21.1 for information on interpreting per person estimates).

Health expenditure can be categorised as either primary or secondary/tertiary expenditure. Primary care includes services for the entire population, like public and community health, as well as patient-initiated services such as general practitioner visits. Secondary and tertiary care, typically accessed via referral, covers specialist consultations, procedures, diagnostic tests, prescribed medications from specialists, and hospital treatments.

Looking at expenditure by levels of health care (Table 3.21-1), 34% of total health expenditure in 2022–23 for First Nations people was on primary health care services ($4,225 million). This consists of:

- expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs through the IAHP ($855 million for the primary health care component)

- unreferred Medicare services ($373 million)

- PBS section 85 ($467 million)

- PBS section 100 expenditure on PBS items supplied to approved Aboriginal Health Services under the Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services (RAAHS) Program ($48 million)

- other recurrent primary health care expenditure ($2,483 million).

The remaining 66% was on secondary and tertiary health services ($8,061 million). This was predominantly hospital services ($6,717 million). It also includes expenditure on referred Medicare services ($364 million), section 100 pharmaceuticals (excluding RAAHS expenditure) ($170 million), hospital chronic disease programs through the IAHP ($6 million), and other recurrent secondary and tertiary expenditure ($804 million) (Table D3.21.5).

On a per person basis, this was equivalent to $4,176 per person on primary health services, and $7,969 per person on secondary/tertiary health services (Table D3.21.6).

Table 3.21-1: Health expenditure on primary and secondary/tertiary health services, by area of expenditure, 2022–23

| Primary expenditure ($ million) |

Secondary/tertiary expenditure ($ million) |

Total expenditure ($ million) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | . . | 6,717 | 6,717 |

| Medicare services(a) | 373 | 364 | 737 |

| Benefit-paid pharmaceuticals (PBS) – Section 85 | 467 | . . | 467 |

| Benefit-paid pharmaceuticals (PBS) – Section 100(b) | 48 | 170 | 218 |

| Australian Government First Nations-specific health programs under the IAHP(c) | 855 | 6 | 861 |

| Other(d) | 2,483 | 804 | 3,286 |

| Total | 4,225 | 8,061 | 12,286 |

(a) Includes MBS expenditure except MBS in hospital items which are included in hospital expenditure. Unreferred allied health is included in primary expenditure and referred allied health is included in secondary/tertiary expenditure.

(b) PBS section 100 primary expenditure refers to PBS items supplied to approved Aboriginal Health Services under the Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services (RAAHS) Program.

(c) Australian Government expenditure on the Indigenous Australians' Health Programme (IAHP), where IAHP secondary expenditure refers to expenditure on in hospital Chronic Disease Programs.

(d) Includes other recurrent expenditure on health not elsewhere classified. See Table D3.21.5 for details.

Source: Table D3.21.5. AIHW health expenditure database; AIHW disease expenditure database; Government Health Expenditure National Minimum Data Set; AIHW analysis of the PBS subsidised prescriptions data and MBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing’s Enterprise Data Warehouse; Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing Financial Journaling System.

Australian Government expenditure

During 2022–23, the Australian Government’s health expenditure for First Nations people was $5,708 per person. Of this amount:

- 31% ($1,776 per person) was spent on admitted patient services in public hospitals

- 12% ($658) was spent on non-admitted patient services in public hospitals

- 3.1% ($175) was spent on admitted patient services in private hospitals

- 12% ($666) was spent on MBS services

- 11% ($636) was spent on PBS medicines

- 15% ($851) was spent on Aboriginal Community Controlled Health services and other initiatives funded under Australian Government First Nations-specific health programs

- 17% ($946) was spent on other recurrent health expenditure (Table D3.21.4).

State and territory government expenditure

In 2022–23, state and territory government health expenditure for First Nations people was $4,832 per person. Of this amount:

- 57% ($2,761 per person) was spent on admitted patient services in public hospitals

- 21% ($1,024) was spent on non-admitted patient services in public hospitals

- 0.1% ($4) was spent on admitted patient services in private hospitals

- 22% ($1,043) was spent on other recurrent health expenditure (Table D3.21.4).

Expenditure by remoteness

The following data by remoteness should be interpreted with caution given limitations of the geographic information used. Both PBS and MBS expenditure by remoteness is based on the postcode of a person’s mailing address. However, if the mailing address is a PO Box, the postcode may not reflect where the person lives. Additionally, some postcodes span multiple remoteness categories, so expenditure is distributed between these areas based on population estimates. Hospitalisation expenditure is allocated based on the remoteness area of the hospital, and may thus not reflect the remoteness area of a patient’s residential address.

In 2022–23, expenditure estimates by remoteness were produced for expenditure on admitted patient care in public and private hospitals, Medicare services (through the MBS), benefit-paid pharmaceuticals (through the PBS), and Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP) initiatives. These estimates covered 59% of the total health expenditure for First Nations people, as the remaining 41% could not be reliably allocated by remoteness categories.

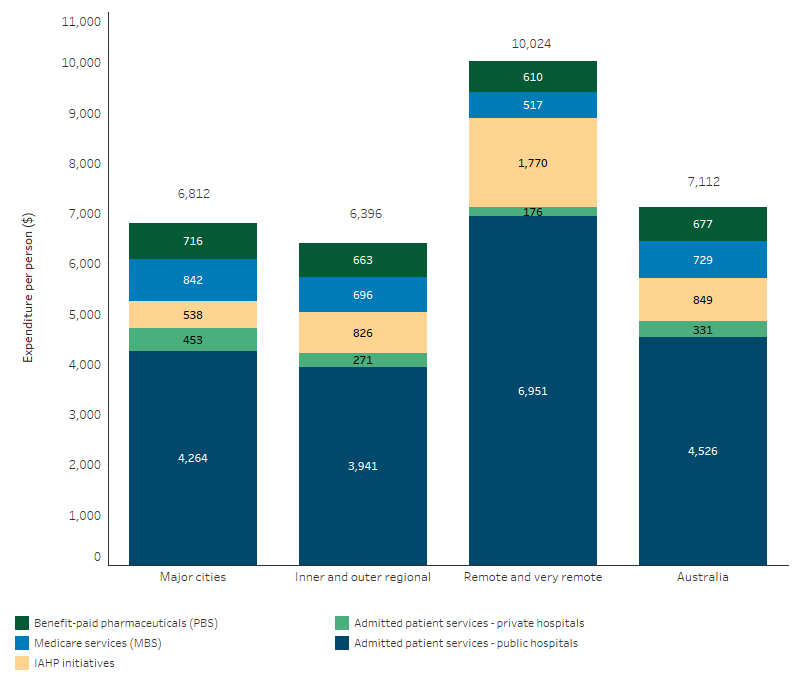

In 2022–23, total (government and non-government) expenditure per person on these selected health services for First Nations people was $10,024 per person in Remote and very remote areas, $6,396 per person in Inner and outer regional areas, and $6,812 per person in Major cities (Table D3.21.7, Figure 3.21.1). The average expenditure per person for First Nations people was 1.5 times as high in Remote and very remote areas compared with Major cities. This is partly due to the higher rate of hospitalisations for First Nations people in Remote and Very remote areas compared with other parts of Australia (see measure 1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisation), but may also reflect higher costs of delivering services in these areas.

Figure 3.21.1: Health expenditure per person for First Nations people on selected health services, by remoteness area, 2022–23

Note: Excludes health expenditure on non-admitted patient services, patient transport, dental services, community health services other than ACCHSs, other professional services, public health services, aids and appliances, research and health administration. In Remote and very remote areas the PBS total is inclusive of expenditure under the PBS s100 Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services (RAAHS) Program.

Source: Table D3.21.7. AIHW health expenditure database; AIHW disease expenditure database; Government Health Expenditure National Minimum Data Set; AIHW analysis of the PBS subsidised prescriptions data and MBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse; and ABS population estimates and projections (AIHW 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

Expenditure on Medicare Benefits Schedule

The Australian Government subsidises the costs of a broad range of health services through the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS), covering all or part of the costs of these services. MBS expenditure data covered here includes general practitioner (GP) attendances, specialist attendances, imaging, pathology, surgical and other procedures, and other unreferred services (including enhanced primary care services used to manage complex health conditions, and practice nurses).

Note that previous versions of this measure used a different approach to estimate expenditure on Medicare services for First Nations people (see Box 3.21.2). Data in this measure and the related tables should not be compared with data in previous releases.

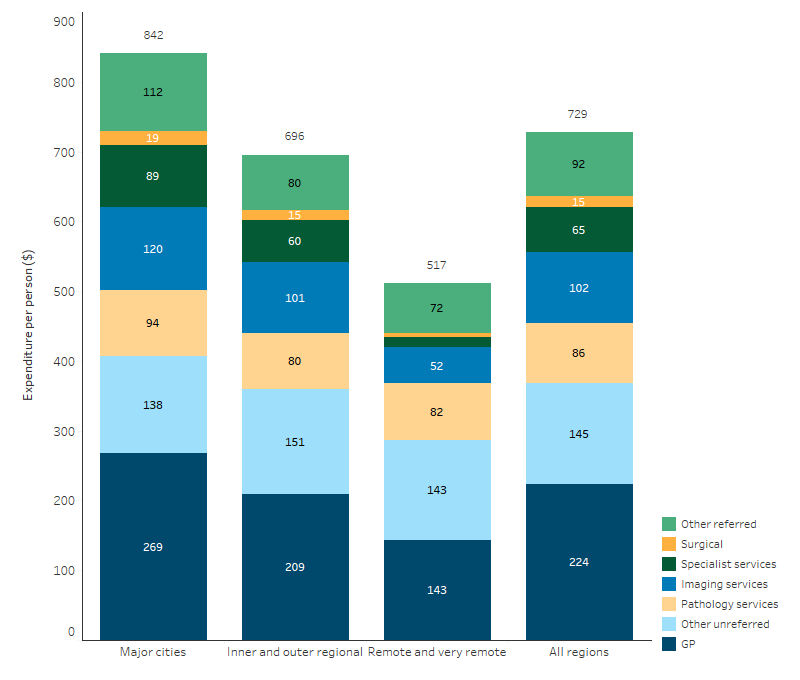

In 2022–23, total MBS expenditure (including government contributions and individual co-contributions) per person on selected services for First Nations people was $729. Per person MBS expenditure for First Nations people decreased with remoteness, ranging from $842 per person for those living in Major cities, $696 per person for those in Inner and outer regional areas and $517 per persons for those living in Remote and very remote areas (Table D3.21.8, Figure 3.21.2).

Figure 3.21.2: MBS expenditure per person for First Nations people on selected services, by remoteness area, 2022–23

Note: Includes Australian Government and non-government expenditure. Excludes MBS in hospitals, which is captured in hospital expenditure. Some totals may not equal the sum due to the weighting method applied.

Source: Table D3.21.8. AIHW analysis of Medicare Benefits Schedule data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse, and ABS population estimates and projections (AIHW 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

First Nations-specific health program expenditure

For health services tailored to the needs of First Nations people, the Australian Government spent $1,157 million on First Nations-specific health programs through the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing in 2022–23. This includes expenditure on ACCHSs and other health initiatives funded under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme ($999 million), as well as First Nations-specific health programs funded outside the IAHP ($158 million) (Table D3.21.9).

Note some non-Indigenous Australians use these programs. Of expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs funded under the IAHP, $861 million was estimated to be for First Nations people (Table D3.21.1). Data on IAHP expenditure presented in this measure are recurrent expenditures only and do not include capital expenditures, and therefore may not match reporting on total program expenditure by the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing.

Expenditure on hospitalisations

In 2022–23, for First Nations people, total (government and non-government) spending on hospital services was $6,717 million:

- 95% ($6,379 million) was spent on public hospital admitted and non-admitted patient services

- 5% ($338 million) was spent on private hospital admitted patient services (Table D3.21.1).

In 2022–23, the average expenditure per person on hospital services for First Nations was $6,641, consisting of $4,602 per person on public hospital admitted patient services, $1,704 on public hospital non-admitted patient services, and $334 per person on admitted patient private hospital services (Table D3.21.1).

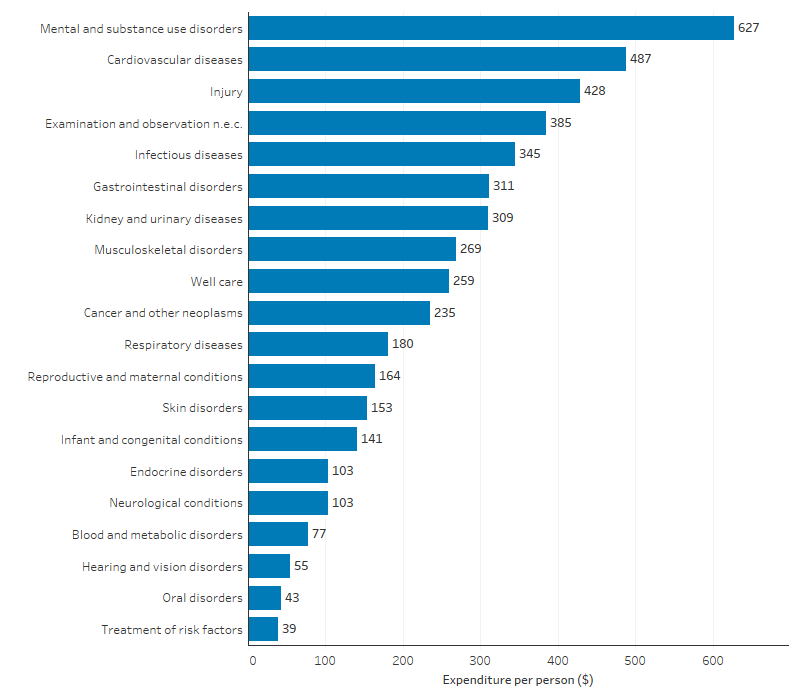

Admitted patient hospital expenditure can be allocated to the specific disease or injury it related to, based on diagnosis information, using the AIHW disease expenditure database. In 2022–23, of $4,994 million in admitted patient expenditure in public and private hospitals, $4,768 million could be allocated by burden of disease group. Of this, expenditure was highest for mental health conditions and substance use disorders ($627 per person). This was followed by cardiovascular diseases ($487 per person) and injury ($428 per person) (Table D3.21.10, Figure 3.21.3).

Figure 3.21.3: Expenditure per person for First Nations people on hospitalisations in public and private hospitals, by disease group, 2022–23

n.e.c. not elsewhere classified.

Note: Allocation of expenditure by disease group uses the methodology as used in Health system spending on disease and injury in Australia 2022–23 (AIHW 2024a). The estimates are not comparable with those published previously, which used different groupings. Well care includes expenditure for services that are typically routine examinations, general examinations without specific complaints or diagnoses, or administrative in nature, routine dental checkups and cleaning, pregnancy and postpartum care, family planning, counselling services, social services and donations of organs and tissue.

Source: Table D3.21.10. AIHW disease expenditure database; and ABS population estimates and projections (AIHW 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

Hospitalisations for conditions that could potentially have been prevented through provision of appropriate preventative health interventions and early disease management in primary care and community-based care settings are referred to as potentially preventable hospitalisations. In 2022–23, total expenditure for First Nations people for selected potentially preventable hospitalisations was $654 million. This equated to $646 per person, including:

- $278 per person for chronic conditions

- $244 per person for acute conditions

- $153 per person for vaccine-preventable conditions (Table D3.21.11).

Note that a single hospitalisation can be associated with more than one of the above condition categories, and so the above categories do not sum to the total of $646 per person. Note also that COVID-19 is not included in these data, which are based the National Health Care Agreement definition of selected potentially preventable hospitalisations.

Comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

Comparing differences in health outcomes between First Nations and non-Indigenous Australians with differences in per capita health expenditure can indicate whether there is unmet need for health care. Health expenditure should reflect the relative need for health services – it should be higher for population groups with higher levels of need.

The most recent data from the Australian Burden of Disease Study (ABDS) showed that in 2018, the age-standardised total burden of disease for First Nations people was 2.3 times that for non-Indigenous Australians.

Note that the burden of disease comparison ratio is based on age-standardised rates, and therefore it is not comparable to the total health expenditure ratio reported in this measure, which is not adjusted for age (as data by age are not available for all areas of expenditure, see Box 3.21.1). By age group, the gap in disease burden ranges between 1.4 and 3.0. The gap also varies by disease group (age-standardised rate ratios from 0.9 to 6.3).

While a useful indicator of need, burden as measured in the ABDS reflects the impact of disease and injury on an individual’s health compared with the ideal of perfect health and does not necessarily reflect their need for or use of health services, or the cost of providing these at a population level. Further, the disease burden estimates incorporate a component of access to services, as the non-fatal burden estimates are derived from data on diagnosed cases of disease. This means that in burden of disease estimates, a person must have already sought health care in order to obtain a diagnosis. Therefore, comparisons of burden rates may not reflect variations in need.

Comparisons by area of expenditure

In 2022–23, nationally, total health expenditure for First Nations people was estimated to be $12,146 per person on average, compared with $8,901 per person for non-Indigenous Australians. This corresponds to $1.36 spent per person for First Nations people for every $1 spent per person for non-Indigenous Australians (ratio 1.4) (Table D3.21.1). It should be noted that this ratio combines spending from a diverse range of health services, and does not reflect experiences of the health system at the individual level.

For primary health services, expenditure for First Nations people was $4,176 per person, which was 1.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians ($3,080 per person). This includes expenditure for unreferred services under the MBS (which was lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians), most PBS expenditure (lower for First Nations people) and Australian Government expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs under the IAHP (predominantly for First Nations people). For secondary/tertiary health services (mainly hospital services), expenditure was $7,969 per person for First Nations people, compared with $5,822 for non-Indigenous Australians, which is 1.4 times as high (Table D3.21.6).

Per person MBS expenditure for First Nations people was about two-thirds (0.65 times) that of non-Indigenous Australians, with $729 spent per person for First Nations people compared with $1,117 per person for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.21.1). After adjusting for differences in the age-structure between the two populations, MBS expenditure for First Nations people was 0.9 times that of non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.21.15).

Per person PBS expenditure for First Nations people was $677 per person, compared with $758 per person for non-Indigenous Australians, which is a ratio of 0.9 (Table D3.21.1). After adjusting for differences in the age-structure between the two populations, PBS expenditure for First Nations people was 1.4 times that of non-Indigenous Australians (excluding expenditure under the s100 Remote Area Aboriginal Health Services program which could not be disaggregated by age) (Table D3.15.4) (see measure 3.15 Access to prescription medicines).

In 2022–23, for First Nations people, per person expenditure on secondary and tertiary health care services was 1.9 times the expenditure for primary health care services. Similarly, for non-Indigenous Australians, the expenditure on secondary and tertiary health care services was 1.9 times the expenditure for primary health care services (Table D3.21.6).

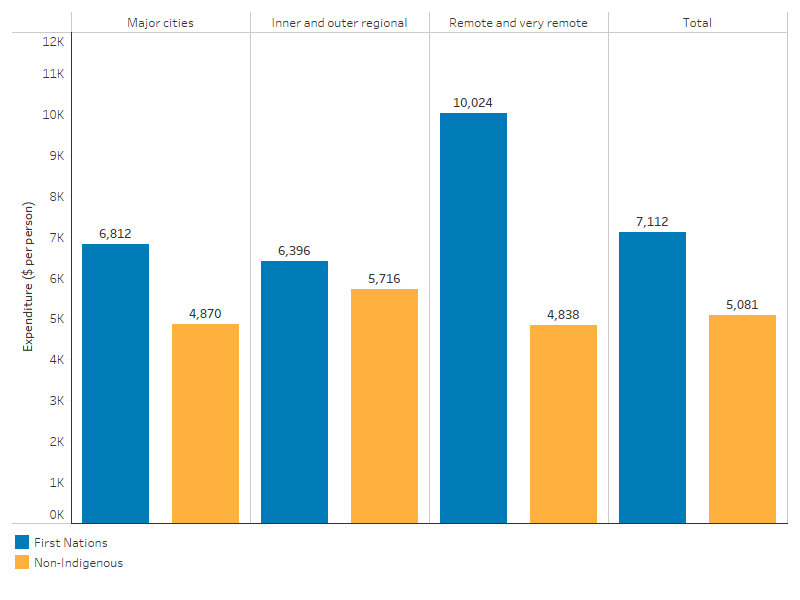

Expenditure by remoteness compared with non-Indigenous Australians

For the areas of health expenditure which could be allocated by remoteness (hospitals, MBS, PBS, and IAHP initiatives), per person expenditure was higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians across all remoteness areas, with the largest difference in Remote and very remote areas (Table D3.21.7, Figure 3.21.4).

Figure 3.21.4: Health expenditure per person on selected health services, by Indigenous status and remoteness area, 2022–23

Note: Excludes health expenditure on non-admitted patient services, patient transport, dental services, community health services other than ACCHSs, other professional services, public health services, aids and appliances, research and health administration.

Source: Table D3.21.7. AIHW health expenditure database; AIHW disease expenditure database; Government Health Expenditure National Minimum Data Set; AIHW analysis of the PBS subsidised prescriptions data and MBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse; and ABS population estimates and projections (AIHW 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

Expenditure on hospitalisations compared with non-Indigenous Australians

In 2022–23, per person expenditure on hospital services for First Nations people was 1.7 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians ($6,641 compared with $4,010 per person). Looking in more detail:

- For public hospital services (admitted and non-admitted patient services), per person expenditure for First Nations people was 2.0 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians ($6,306 per person compared with $3,079 per person) (Table D3.21.1).

- For private hospital services (admitted patient services only), per person expenditure for First Nations people was less than half that for non-Indigenous Australians (ratio of 0.4, $334 compared with $931 per person) (Table D3.21.1).

- When calculated as a cost per hospitalisation (separation), rather than a cost per person, expenditure on hospital services was lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians:

– In public hospitals (admitted and non-admitted patient services), expenditure per hospitalisation was $7,555 for First Nations people, compared with $8,936 per hospitalisation for non-Indigenous Australians.

– In private hospitals (admitted patient services only), expenditure was $3,233 per hospitalisation for First Nations people, compared with $4,866 per hospitalisation for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.21.13).

The lower cost per hospitalisation for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians may be related to factors such as differences in the age structure of the two populations, and differences in rates of hospitalisation for particular diagnoses. This will be further explored in a future update.

Estimates of admitted patient expenditure by burden of disease group show that in 2022–23, on a per person basis, expenditure on hospitalisations per person was higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians in almost all diagnosis categories, with the highest differences for:

- mental and substance use disorders ($627 per person compared with $210 per person)

- kidney and urinary diseases ($309 per person compared with $102 per person)

- infectious diseases ($345 per person compared with $155 per person)

- injury ($428 per person compared with $266 per person)

- well care – for example routine examinations and check-ups (including dental), pregnancy and postpartum care (excluding any complications of pregnancy or birth), family planning and other services ($259 per person compared with $157 per person) (Table D3.21.10).

Looking at the average per person expenditure across the whole population, expenditure for First Nations people was lower than for non-Indigenous Australians for treatment of:

- cancer and other neoplasms ($235 per person compared with $336 per person)

- musculoskeletal disorders ($269 per person compared with $346 per person)

- hearing and vision disorders ($55 per person compared with $96 per person) (Table D3.21.10).

However, when looking by age group, per person expenditure in these three diagnosis categories was higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians in most age groups (Table D3.21.12). This suggests that the younger demographic composition of the First Nations population may explain some of the higher average expenditure in these disease groups for non-Indigenous Australians.

Expenditure on potentially preventable hospitalisations in 2022–23 totalled $646 per person for First Nations people, compared with $249 per person for non-Indigenous Australians. The difference in expenditure for potentially preventable hospitalisations due to chronic conditions was $155 per person, with a difference of $148 per person due to acute conditions, and $119 per person due to vaccine preventable conditions. Note that these do not sum to the total gap ($398 per person), as a single hospitalisation can have more than one potentially preventable condition recorded.

Looking at specific conditions, the difference in expenditure was highest for:

- diabetes complications – $60 higher per person for First Nations people

- pneumonia and influenza (vaccine-preventable) – $59 higher per person

- chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – $50 higher per person (Table D3.21.11).

Note that the above ranking was done after excluding ‘other vaccine-preventable conditions’ (collectively a gap of $62 per person), since this consists of several different vaccine-preventable conditions.

Changes over time

From 2014–15 to 2022–23, total health expenditure increased from $7,011 million to $12,286 million, an average annual growth of 7.3%, compared with an annual growth of 3.8% for non-Indigenous Australians.

Expenditure was also calculated on a per person basis, for a shorter period from 2016–17 to 2022–23. These per person trends are limited to 2016 onwards, due to a large non-demographic increase in Census counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people between 2016 and 2021 (see Understanding change in counts of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and Guide to using historical estimates for comparative analysis and reporting).

Change in per person expenditure indicates change in expenditure after accounting for population growth. From 2016–17 to 2022–23, total health expenditure per person for First Nations people increased by 4.3% per annum after accounting for inflation, rising from $9,447 per person to $12,146 per person. During this period, the ratio of expenditure for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians fluctuated around an average ratio of 1.3, from 1.2 in 2016–17 to 1.4 in 2022–23 (Table D3.21.14).

Australian Government and state/territory governments expenditure

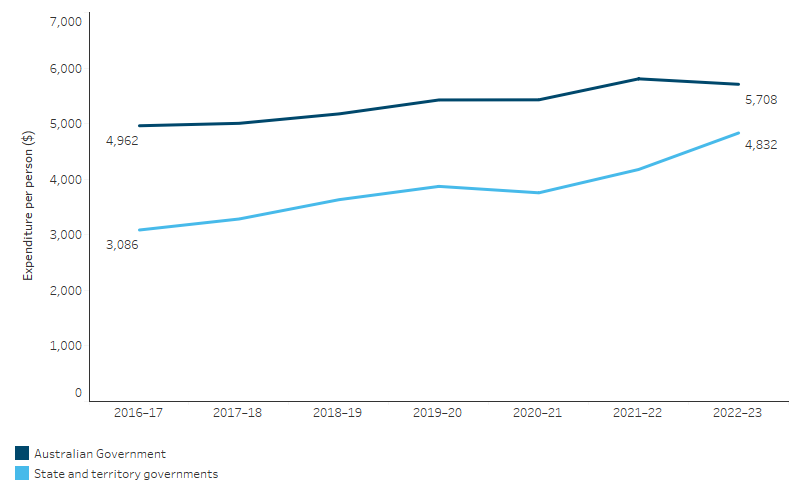

From 2016–17 to 2022–23, Australian Government health expenditure per person for First Nations people increased by 2.4% per annum when adjusted for inflation, at $5,708 per person in 2022–23, compared with $4,962 per person in 2016–17. This growth was driven primarily by growth in expenditure on admitted and non-admitted patient services in public hospitals (Table D3.21.4).

From 2016–17 to 2022–23, state and territory government health expenditure per person for First Nations people increased by 7.8% per annum when adjusted for inflation, from $3,086 per person to $4,832 per person. The main driver of growth in state and territory government health expenditure was also spending on admitted and non-admitted patient services in public hospitals (Table D3.21.4, Figure 3.21.5).

Figure 3.21.5: Australian Government and state/territory government health expenditure per person for First Nations people, 2016–17 to 2022–23 (inflation adjusted)

Note: Expenditure from 2016–17 to 2022–23 is expressed in 2022-23 prices, adjusted for inflation.

Source: Table D3.21.4. AIHW health expenditure database; AIHW disease expenditure database; Government Health Expenditure National Minimum Data Set; AIHW analysis of the PBS subsidised prescriptions data and MBS data in the Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing's Enterprise Data Warehouse; Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing Financial Journaling System and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2024) for calculation of per person expenditure.

Australian Government expenditure on First Nations-specific primary health care programs

For health services tailored to the needs of First Nations people, the Australian Government allocated $1,157 million on First Nations-specific health program expenditure through the Department of Health, Disability and Ageing in 2022–23. This was an increase from $942 million in 2013–14 when adjusted for inflation, an average increase of 2.3% per annum in real terms (Table D3.21.9, Figure 3.21.6).

On a per person basis, from 2016–17 to 2022–23, expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs funded by the Australian Government increased by 0.5% per annum in real terms, from $1,110 per First Nations person to $1,144 per First Nations person.

Note that some non-Indigenous Australians receive services through First Nations-specific health programs (in 2022–23, an estimated 12% of the expenditure was for non-Indigenous Australians). In calculating the per person figures, all expenditure is included in the numerator, but the denominator is restricted to the First Nations population.

Figure 3.21.6: Expenditure by the Australian Government on First Nations-specific health programs, 2013–14 to 2022–23 (inflation adjusted)

1. IAHP refers to Australian Government expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme.

2. Non-IAHP refers to Australian Government expenditure on First Nations-specific health programs outside of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme.

3. Expenditure from 2013–14 to 2022–23 is expressed in 2022-23 prices, adjusted for inflation.

Source: Table D3.21.9. AIHW analysis of Department of Health, Disability and Ageing cost centres.

Hospital expenditure

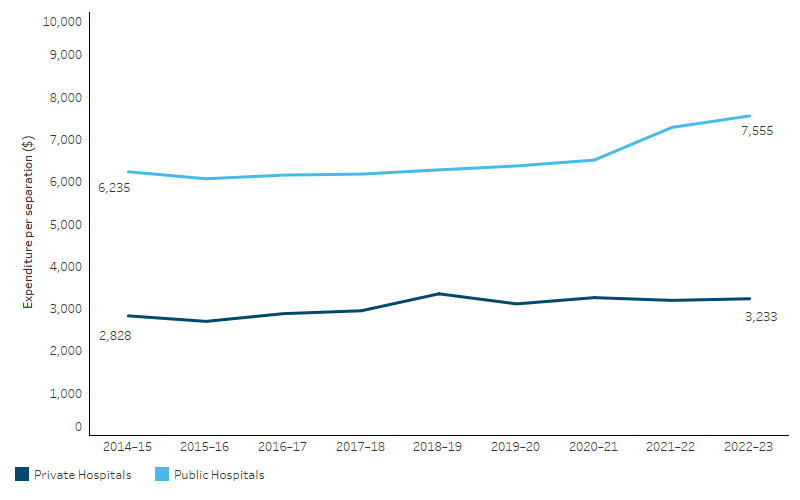

From 2014–15 to 2022–23, total public admitted patient hospital expenditure for First Nations people increased from $2,596 million to $4,655 million when adjusted for inflation, corresponding to a growth of 7.6% per annum. For private hospitals, admitted patient expenditure for First Nations people increased from $129 million to $338 million when adjusted for inflation, an increase of 13% per annum.

This increase in hospital expenditure reflects not only an increase in the number of hospitalisations that occurred in this period (see also measure 1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisation), but also an increase in the cost per hospitalisation.

For First Nations people between 2014–15 and 2022–23:

- expenditure per hospitalisation for public hospital admitted patient services increased by 2.4% per annum when adjusted for inflation, from $6,235 per hospitalisation to $7,555

- expenditure per hospitalisation for private hospital admitted patient services increased by 1.7% per annum when adjusted for inflation, from $2,828 per hospitalisation to $3,233 (Table D3.21.13, Figure 3.21.7).

Admitted patient expenditure per hospitalisation is lower for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians. The ratio of expenditure per hospitalisation for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians remained stable between 2014–15 to 2022–23 for public hospitalisations, at around 0.8. For private hospitals, the ratio of expenditure per hospitalisation for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians increased from 0.5 to 0.7 over this period (Table D3.21.14).

Figure 3.21.7: Admitted patient hospital expenditure per hospitalisation for First Nations people, 2014–15 to 2022–23 (inflation adjusted)

Note: Expenditure from 2014–15 to 2022–23 is expressed in 2022–23 prices, adjusted for inflation.

Source: Table D3.21.13. AIHW Disease expenditure database.

Research and evaluation findings

Australia was the first country to comprehensively estimate how much was spent on health services for its First Nations population. A report published in 1998, estimated that per person health expenditure from all sources for First Nations people in 1995–1996 was 8% higher than for non-Indigenous people (Deeble et al., 1998). As the health status of First Nations people was much worse than for non-Indigenous people, with a life expectancy gap of at least 12 years, it was clear that the 8% higher per person expenditure was not enough to address the much greater need for health services of First Nations people (Goss 2022). This greater need is rooted in the enduring impacts of colonisation, which caused widespread violence, disease, dispossession, and the forced removal of children – leading to intergenerational trauma that continues to drive disadvantage and poor physical and mental health through social systems that sustain inequality (Australian National University 2020; Paradies 2016; Paradies & Cunningham 2012). First Nations health expenditure estimates have continued to be refined over the years (Parliament of Australia 2022), including estimates being made of First Nations health expenditure by remoteness and by disease (AIHW 2013b, 2013c).

The AIHW report on ‘First Nations people and the health system’ discusses how socioeconomic factors such as income, employment, housing, and education impact health outcomes and access to health services. It highlights that individuals with lower incomes, including First Nations people, tend to rely more on publicly provided services and have a higher likelihood of presenting to hospitals for primary health care needs. This report also underscores the critical role of government health funding in delivering essential health services to First Nations people. By providing targeted financial resources, the government helps improve health outcomes and access to health care for First Nations people, ultimately contributing to their overall wellbeing and quality of life (AIHW 2024c).

Evidence suggests that the higher expenditures in rural and remote areas are largely related to hospital services and grants to Indigenous-specific primary health care services, and partly reflects higher costs of delivering health care services in those areas (AIHW 2013c). The cost of providing high-quality primary health care services increases with remoteness, largely due to higher human resource expenses – accounting for 69–85% of recurrent costs, with doctors’ salaries alone comprising 47–65%. Costs per consultation ranged from $50 to $149, with smaller practices facing higher per capita and per consultation costs due to fewer registered patients. Although many small rural communities are among the most socioeconomically deprived in Australia, their needs for good primary health care are among the greatest. In the absence of locally available services, financial and geographical barriers to accessing alternative sources of primary health care have contributed to high levels of preventable disease and morbidity resulting from delayed or foregone care (Thomas et al. 2017).

First Nations-specific primary health services are crucial for improving the health of First Nations people through prevention, early intervention, and health education. The Australian Government funds these services through the IAHP and collects data using the Online Services Report (OSR) and national Key Performance Indicators (nKPI) collections. In 2023–24, around 425,000 of the estimated 1.0 million First Nations population were clients of organisations reporting to the OSR collection. Of the 213 organisations providing care, 69% (147) were ACCHSs, which played a central role in service delivery. ACCHSs served 85% of all clients reported in the OSR including 84% who were First Nations people, and provided 3.8 million episodes of care during the year. ACCHSs employed a higher proportion of First Nations staff (51%) compared with non-ACCHSs (40%). This data underscores the critical reliance of First Nations people on ACCHSs for culturally appropriate primary health services (AIHW 2025).

Despite strong preference for Aboriginal Medical Services (AMS) and ACCHSs, 142,200 First Nations people did not use them as their usual source of care, even though it was their preferred option. While nearly all who preferred a mainstream GP had one as their usual provider (88%), only 64% of those preferring an AMS and ACCHS were able to access one. This unmet need included 87,000 people with long-term conditions, 56,000 with disability, 30,000 adults with high psychological distress, and 24,000 who experienced unfair treatment in the past year. Geographic disparities were also evident, with the largest unmet needs in major cities (68,000), inner regional areas (42,000), New South Wales (57,000), and Queensland (39,000). Socioeconomic disparity further compounded this gap, with 65,000 in the lowest Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) quintiles affected. This shows a significant mismatch between service preference and availability, particularly for those with higher health and social needs (AIHW 2024d).

Chronic diseases are major contributors to the gap in life expectancy between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians. The Australian Government implemented the Closing the Gap PBS Co-payment Measure in 2010 to reduce prescription drug co-payments and thereby improve access to PBS medicines for First Nations people with chronic diseases or risk factors of chronic diseases. Eligible patients could register at participating general practices or ACCHS clinics. Among registered patients, the incentive reduced co-payments from $33.30 per prescription to about $5.40 per prescription (price adjusted) for non-concessional patients. The co-payment of $5.40 was eliminated for concessional patients. The reduction of co-payments increased the use of medications for both concessional and non-concessional patients (Trivedi & Kelaher 2020). Previous economic evaluation studies on removing out-of-pocket costs for prescriptions for patients who have had a myocardial infarction have suggested that reducing medication co-payments could improve adherence to treatment and reduce serious complications, therefore, improving health outcomes without necessarily increasing the total expenditure on health care in the longer term (Choudhry et al. 2011; Choudhry et al. 2014).

A data-linkage study of the Queensland population showed that large out-of-pocket costs associated with health care are a significant barrier to equitable access. First Nations people with cancer in Australia pay significantly less on co-payments for services covered under Medicare than non-Indigenous people with cancer in the first 3 years after diagnosis. The difference could be explained by the fact that First Nations people with cancer were less likely to access services covered by Medicare, such as pathology tests, diagnostic imaging, as well as specialists, and radiotherapy and therapeutic nuclear medicine services. It was also possible that they may have accessed these services through state and territory funded programs, and therefore, could not be captured in the study data. In order to account for these differences in access patterns, researchers conducted additional modelling of the scenario and found that if First Nations people had the same rate of access to services covered under Medicare as non-Indigenous people, they would incur much higher out of pocket expenditure for co-payments. The findings suggest that although Australia's universal health care policies are supporting equity, there is still substantial inequity in terms of access to services for First Nations people with cancer. However, the study has limitations, including the limited costs included and the inability to adjust for co-morbidities and educational level (Callander et al. 2019).

A qualitative study conducted in 2023–2024 investigated the experiences of First Nations families in remote Far West South Australia with out-of-pocket health care expenditure (OOPHE). The study revealed that a large portion of these costs came from travel expenses, including fuel, vehicle maintenance, and accommodation, with some trips exceeding $2,000. The Cashless Debit Card (CDC) also compounded financial barriers by restricting access to services and accommodation. Many families reported having to cancel or delay medical appointments due to the financial strain, which worsened their health conditions. To manage these costs, families often resorted to borrowing money or selling personal assets. Despite these hardships, family and community support, along with cultural practices and connection to Country, helped ease some of the psychological and financial burdens they faced (Ryder et al. 2024).

Another data-linkage study analysed MBS and PBS expenditure between 2010–11 and 2019–20 by state and territory, remoteness, and First Nations demography to assess funding equality in meeting the health needs of remote First Nations populations in the Northern Territory (Zhao et al. 2022). The data have shown that the Northern Territory receives the lowest per-capita payments from MBS and PBS, despite its greater remoteness and health needs (Zhang et al. 2018). The unmet needs were potentially due to the unique primary health care model in remote areas. Unlike mainstream primary health care in Australia, which is general practice, remote primary health care delivery is primarily led by Aboriginal Health Practitioners and Remote Area Nurses who provide first contact care. However, some of these services fall outside MBS eligibility criteria, posing significant cost to patients. Additional barriers such as health literacy, language and cultural barriers to communication, and limited access to transportation deter residents of remote areas from utilising health care services. Initiatives such as the Commonwealth health financing reforms, for example Health Care Homes, which provide blended payment for team-based care, are highly relevant to the Northern Territory but will need to be calibrated to reflect the service delivery in remote and very remote settings (Australian Government Department of Health 2019).

A 2014 independent report commissioned by the NACCHO was the first detailed health economics study of ACCHSs and related resource and funding issues in Australia. The report included an assessment and evaluation of the economic and health value derived from the ACCHS sector and an evaluation of government policy and expenditure on ACCHSs and First Nations health more generally. The report also investigated additional cross-sector benefits to the Australian economy provided by ACCHSs, such as employment, economic independence, and education. The report found that, as First Nations people comprise 3% of the Australian population and have a relative need of at least twice the rest of the population because of much higher levels of illness, it is important for funding to be more commensurate with need and be better distributed (Alford 2014).

Additionally, a 2018 literature review on ACCHSs compared with mainstream health services found that ACCHSs deliver more culturally appropriate, comprehensive and trusted care, particularly for chronic disease management and antenatal services. First Nations patients reported higher levels of satisfaction and adherence to treatment when using ACCHSs, which were shown to handle more complex cases than mainstream services. Though ACCHSs may have higher upfront costs, they are cost-effective in the long term, as they reduce hospital stays and improve clinical outcomes. Collaborative care models, like partnerships between ACCHSs and mainstream providers, further enhance care access and outcomes, demonstrating that investments in ACCHSs lead to both improved health results and financial savings by preventing more costly interventions later on (Campbell et al. 2018; Mackey et al. 2014).

Research in the Northern Territory found that investing $1 in primary care in remote First Nations communities was found to save $3.95–$11.75 in hospital costs, in addition to benefits for individual patients. High levels of primary care utilisation were associated with decreases in avoidable hospitalisations, deaths and years of life lost (Zhao et al. 2014). More research is required into the cost-effectiveness of ACCHSs to provide evidence for advantages, health gains and strategies that improve health outcomes (Dalton & Carter 2018), as well as gaps and barriers that need to be addressed (Alford 2014).

In 2017, the Australian Government announced it was undertaking a national evaluation of its investment in First Nations primary health care which occurs primarily through the IAHP. The evaluation has a whole of system, person-centred approach that not only focuses on the appropriateness and effectiveness of the IAHP, but its interactions and influence on other parts of the primary health care and wider health system. It is drawing on the perspectives of First Nations stakeholders at different levels of the system and aims to facilitate learning across these levels. The Department of Health, Disability and Ageing is working with the IAHP Yarnes Health Sector Co-design Group on finalising the evaluation in the near future.

A component of this evaluation was the IAHP Economic Evaluation Phase One which was published in mid-2018. It focused on the return on investment of the IAHP as measured by potentially preventable hospitalisations and the relative costs of Indigenous-specific compared with mainstream primary health care services. The report showed that higher attendance at ACCHSs reduced the likelihood of hospital admission, as well as providing health gains. While the provision of care through mainstream services may be cheaper, it is likely to be associated with worse health outcomes due to less comprehensive and integrated care that may not be culturally competent and may not meet patients’ needs and expectations. These findings were used to demonstrate the cost-effectiveness of ACCHSs, although there were some methodological limitations. For more information, see measure 1.24 Avoidable and preventable deaths (Dalton & Carter 2018).

A systematic review on the scope and quality of economic evaluations of health programs for First Nations people found that, despite substantial investment in efforts to close the gap in health outcomes, there remains limited evidence on what constitutes a cost-effective investment in health care for First Nations communities (Doran et al. 2022).

NACCHO, in partnership with Equity Economics, undertook an analysis of the gap in health expenditure for First Nations people. This report concludes that there remains a large and persistent gap in expenditure on health care for First Nations people given the additional need, estimating an annual shortfall of $4.4 billion, including $2.6 billion in Commonwealth Government expenditure. Moreover, this gap is further compounded by barriers to private health care and the additional costs required for culturally appropriate care needed to close the gap – that is, to ensure First Nations health improves at the rate required to bring it into parity with non-Indigenous Australians (NACCHO & Equity Economics 2022).

A review on the cultural determinants of health for First Nations people highlights the critical role that cultural factors play in health outcomes. Key cultural determinants such as family/community, connection to Country, cultural identity, and self-determination were identified as positively influencing health and wellbeing. Engagement with Country was linked to improved physical activity, diet and social cohesion, which are crucial for better health outcomes. The importance of cultural identity was found to be a protective factor against trauma, playing a key role in fostering resilience. Additionally, self-determination emerged as a fundamental component for empowering First Nations people to control their health and wellbeing, addressing broader systemic health inequities. Community-controlled organisations also play a significant role in delivering flexible and culturally appropriate care, further contributing to improved health outcomes (Verbunt et al. 2021).

Implications

Issues of equity are particularly important in this performance measure. First Nations people view health holistically, emphasising the interconnectedness of Country, culture, and First Nations knowledge systems. Wellbeing is achieved through the relationship between people, land, and cultural practices, with First Nations knowledges being essential for health (Biles et al. 2024).

Health inequity for First Nations people is primarily driven by the long-standing impacts of colonisation, which disrupts ties to land, cultural practices, and self-determination. Other key factors include economic inequality, poverty, the adverse effects of racism, and a broader societal lack of understanding of First Nations cultures and worldviews. These interconnected social, economic, and cultural determinants shape health outcomes and perpetuate disparities (Osborne et al. 2013).

Findings in this measure have shown that for total health expenditure, around $1.36 is spent per person for First Nations people for every $1 spent per person for non-Indigenous Australians. However, it is important to note that this ratio is not age-standardised, which means direct comparison with per capita expenditure is problematic.

From 2016–17 to 2022–23, health expenditure per person for First Nations people increased by 4.3% per annum after adjusting for inflation, and the Australian Government's expenditure per person on First Nations-specific health programs grew by an average of 0.5% per annum over this period. Despite the increase in overall health expenditure, it does not fully address the higher burden of disease among First Nations people, which is 2.3 times as high as that of non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022). Moreover, the rates of potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPH) are higher among First Nations people, indicating a lack of timely and adequate primary healthcare services (AIHW 2024b). This situation highlights the need for increased investment in prevention and primary health care to reduce preventable admissions and improve health outcomes for First Nations people.

The significant investment in First Nations health in Australia in recent decades has not yet led to the relative improvements in life expectancy and health outcomes long sought after. It is crucial to recognise that improving health outcomes for First Nations people requires not only investment in clinical services and secondary health care but also in culturally grounded health initiatives that address the underlying determinants of health. Prevention-focused approaches, such as culturally appropriate care and community-led interventions, can help reduce the demand for more costly health services in the long term. Funding gaps in these areas risk exacerbating health disparities if not addressed, underscoring the importance of a comprehensive approach that prioritises both prevention and treatment.

To improve healthcare access and outcomes for First Nations people, it is essential to increase funding for primary healthcare services, enhance access in remote areas, and encourage greater use of the MBS. Additionally, measures that invest in preventive care, improve cultural competence among healthcare providers, boost the number of First Nations healthcare professionals, and that foster collaboration with First Nations communities to support self-determination, will aid delivery of more equitable, culturally appropriate care for First Nations people.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (Health Plan) emphasises the need for culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations peoples. It calls for key changes in the mainstream health system, including eliminating racism, ensuring person- and family-centred care, adopting trauma-aware approaches, building the First Nations health workforce, and promoting holistic health.

The Health Plan highlights that such care is best delivered by the community-controlled sector and outlines partnerships with this sector as essential for improving mainstream services. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap also recognises the community-controlled health sector as best-placed to provide culturally safe care.

The Indigenous Australians' Health Programme (IAHP) plays a crucial role in addressing health expenditure gaps by funding high-quality, culturally appropriate health care services for First Nations people. With a funding allocation of approximately $5.1 billion over 4 years from 2024–25 (Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2025), the IAHP supports more than 140 ACCHSs and other health initiatives to improve access to primary health care across remote, regional, and urban areas. Of this, $2.7 billion is allocated to 120 ACCHSs to deliver culturally appropriate comprehensive primary health care services for First Nations people. Through targeted health activities, such as chronic disease management and child health services, as well as capital works for infrastructure development, the IAHP focuses on improving health care delivery and access.

The First Nations Health Funding Transition Program, announced in October 2022, will review and identify activities which are designed for First Nations people that could be delivered by First Nations-led organisations. This program aligns with the National Agreement on Closing the Gap and supports Priority Reform 2, which focuses on building the community-controlled sector. This work will inform necessary system-level changes to work towards an approach which is led by First Nations-led organisations.

The Australian Government has also announced investment of $100 million for 33 health infrastructure projects to bolster ACCHSs across the country. Key actions include constructing new clinics, renovating existing facilities, and upgrading accommodation for health workers. The locations receiving investment include Maningrida and Wadeye (NT), Cairns and Mount Isa (QLD), the Kimberley and Pilbara (WA), the APY Lands (SA), Dubbo and Broken Hill (NSW), Shepparton and Mildura (VIC), and Hobart and Launceston (TAS). These efforts aim to bridge healthcare access gaps and improve health outcomes for First Nations communities (Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024a, 2024b).

The 2024–25 Australian Government budget includes significant investments to address health inequities for First Nations people. This includes $11.1 million over 5 years from 2023–24 to expand the PBS Co-payment Program, $94.9 million over 2 years to support communicable disease control in First Nations communities, and $10 million to maintain investments to NACCHO to deliver targeted and culturally appropriate mental health supports. For the First Nations health workforce, $4.7 million over 5 years from 2023–24 is for the NT Medical Program to increase the number of First Nations medical practitioners and address recruitment and retention challenges, and $4.0 million over 4 years from 2024–25 for the Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association to continue to support First Nations doctors to become medical specialists (Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024c, 2024d).

The Closing the Gap Commonwealth 2024 Annual Report and Commonwealth 2025 Implementation Plan highlights the Australian Government's ongoing efforts to address health disparities for First Nations people. Key initiatives include expanding Better Renal Services with $73.2 million allocated for 30 new dialysis units in regional and remote areas, ensuring life-saving treatment is available on Country. Additionally, $238.5 million is committed to improving First Nations cancer outcomes, focusing on prevention, screening and workforce growth in ACCHSs (National Indigenous Australians Agency 2025).

There are several aspects of access to care that relate to health inequities and need to be recognised in analysing health expenditure per person. These aspects include geography, discrimination, affordability, and availability, which are detailed in measure 3.14 Access to services compared with need. These issues affect equity and quality of care and the level of need for health care of First Nations people.

An issue to consider when interpreting per person expenditure is the degree of variation between the jurisdictions. Variations in expenditure by jurisdiction are influenced by factors such as the additional costs of delivering services in remote areas, the size of the First Nations population in these areas, and differences in health needs, health services, and health structures. Australia’s constitution and intergovernmental financial transfer arrangements result in differences between the funding and expenditure levels in jurisdictions.

Data on health expenditure by smaller areas of geography would be particularly useful as other health data by smaller geographies become increasingly available. This will aid an understanding of the extent of unmet health need for First Nations people and help to better target areas of greatest need.

The policy context is at Policies and Strategies.

References

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2013a. Indigenous identification in hospital separations data: quality report. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2013b. Expenditure on health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People 2010–11.

-

AIHW 2013c. Expenditure on Health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People 2010–11: An Analysis by Remoteness and Disease. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2022. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. AIHW, Australian Government.

-

AIHW 2024a. Health system spending on disease and injury in Australia 2022–23. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed.

-

AIHW 2024b. Potentially preventable hospitalisations in Australia by small geographic areas, 2020–21 to 2021–22. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed 17 April 2025.

-

AIHW 2024c. First Nations people and the health system. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed 17 March 2025.

-

AIHW 2024d. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and primary health care: patterns of service use, preferences, and access to services.

-

AIHW 2025. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: results from the OSR and nKPI collections. AIHW, Australian Government. Viewed 26 March 2025.

-

Alford K 2014. Economic value of aboriginal community controlled health services.

-

Alford K 2015. Indigenous health expenditure deficits obscured in Closing the Gap reports. The Medical Journal of Australia 203:403.

-

Australian Government Department of Health 2019. Health Care Homes: handbook for general practices and Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health.

- Australian Government Department of Health, Disability and Ageing 2025. Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme primary health care funding model – overview and calculation steps. Department of Health, Disability and Ageing, Australian Government. Viewed 19 March 2025.

-

Australian National University 2020. Mayi Kuwayu Study. Canberra: National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health, Research School of Population Health. Viewed December 2022.

-

Biles BJ, Serova N, Stanbrook G, Brady B, Kingsley J, Topp SM et al. 2024. What is Indigenous cultural health and wellbeing? A narrative review. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific 52.

-

Braveman P & Gruskin S 2003. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 57:254-8.

-

Callander E, Bates N, Lindsay D, Larkins S, Topp SM, Cunningham J et al. 2019. Long-term out of pocket expenditure of people with cancer: comparing health service cost and use for indigenous and non-indigenous people with cancer in Australia. Int J Equity Health 18:32.

-

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

-

Choudhry NK, Avorn J, Glynn RJ, Antman EM, Schneeweiss S, Toscano M et al. 2011. Full Coverage for Preventive Medications after Myocardial Infarction. New England Journal of Medicine 365:2088-97.

-

Choudhry NK, Bykov K, Shrank WH, Toscano M, Rawlins WS, Reisman L et al. 2014. Eliminating medication copayments reduces disparities in cardiovascular care. Health Aff (Millwood) 33:863-70.

-

Dalton A & Carter R 2018. Economic Evaluation of the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme Phase I.

-

Doran C, Bryant J, Langham E, Bainbridge R, Begg S & Potts B 2022. Scope and quality of economic evaluations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health programs: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Public Health 46:361-9.

-

Goss J 2022. Health Expenditure Data, Analysis and Policy Relevance in Australia, 1967 to 2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health:14;9(4):2143.

-

Mackey P, Boxall A-M & Partel K 2014. The relative effectiveness of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services compared with mainstream health service.

-

Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024a. $100 million to improve health infrastructure in First Nations communities: The Hon Linda Burney MP [Press release]. Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government.

-

Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024b. $100 million to improve health infrastructure in First Nations communities: Senator the Hon Malarndirri McCarthy [Press release]. Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government.

-

Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024c. Closing the gap by investing in jobs and housing: Senator the Hon Malarndirri McCarthy [Press release]. Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, Australian Government.

-

Minister for Indigenous Australians 2024d. Fact sheet First Nations budget measures: Budget 2024–25. National Indigenous Australians Agency, Australian Government.

-

NACCHO & Equity Economics 2022. Measuring the Gap in Health Expenditure: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

-

National Indigenous Australians Agency 2025. Commonwealth Closing the Gap 2023 Annual Report and 2024 Implementation Plan. Canberra: Commonwealth Australia.

-

Osborne K, Baum F & Brown L 2013. What works? A review of actions addressing the social and economic determinants of Indigenous health. Issues Paper no. 7 produced for the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Canberra: AIHW.

-

Paradies Y 2016. Colonisation, racism and indigenous health. Journal of Population Research 33:83-96.

-

Paradies Y & Cunningham J 2012. The DRUID study: racism and self-assessed health status in an indigenous population. BMC Public Health 12:131.

-

Parliament of Australia 2022. Indigenous affairs.

-

Ryder C, D'Angelo S, Sharpe P, Mackean T, Cominos N, Coombes J et al. 2024. Experiences and impacts of out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure on remote Aboriginal families. Rural and Remote Health 24:8328.

-

Thomas S, Wakerman J & Humphreys J 2017. What does it cost to provide equity of access to high quality, comprehensive primary health care in rural Australia? A pilot study. . Rural and Remote Health 17.

-

Trivedi AN & Kelaher M 2020. Copayment Incentive Increased Medication Use And Reduced Spending Among Indigenous Australians After 2010: A study of government-sponsored subsidies to reduce prescription drug copayments among indigenous Australians. Health Affairs 39:289-96.

-

Verbunt E, Luke J, Paradies Y, Bamblett M, Salamone C, Jones A et al. 2021. Cultural determinants of health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people – a narrative overview of reviews. 20:181.

-

Whitehead M 1991. The concepts and principles of equity and health. Health Promotion International 6:217-28.

-

World Health Organization 2025. Health equity. WHO.

-

Zhang X, Zhao Y & Guthridge S 2018. Burden of disease and injury study: Impact and causes of illness, injury and death in the Northern Territory 2004-2013. Darwin: Department of Health.

-

Zhao Y, Thomas S, Guthridge S & Wakerman J 2014. Better health outcomes at lower costs: the benefits of primary care utilisation for chronic disease management in remote Indigenous communities in Australia's Northern Territory. BMC health services research 14:463.

-

Zhao Y, Wakerman J, Zhang X, Wright J, VanBruggen M, Nasir R et al. 2022. Remoteness, models of primary care and inequity: Medicare under-expenditure in the Northern Territory. Australian Health Review 46:302-8.