Key messages

- Rates of self-discharge provide an indirect measure of the responsiveness of health services to patient needs. Reasons that patients self-discharge from hospital are varied, and can include dissatisfaction with care, poor communication, long waiting times, and feeling better, as well as external factors such as family and employment responsibilities. These factors, together with a lack of cultural safety, and interpersonal and institutional racism, contribute to the disproportionately higher rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people self-discharging from hospital.

- Between July 2019 and June 2021, the age-standardised rate of discharge at own risk from admitted patient hospital care was 5.2 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians, and the rate at which First Nations people did not wait or left at own risk in emergency departments was 1.5 times as high as non-Indigenous Australians.

- Of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk, the most common principal diagnosis was injury and poisoning (19.2% or 5,190 hospitalisations), followed by mental and behavioural disorders (9.7% or 2,626 hospitalisations), and respiratory diseases (9.1% or 2,466 hospitalisations) (analysis excludes hospitalisations for dialysis).

- Across remoteness areas, the proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk was highest for those living in Very remote areas (7.3% or 6,518 hospitalisations), followed by those in Remote areas (6.3% or 3,848 hospitalisations), with the proportions in non-remote areas ranging from 2.4% to 3.6%.

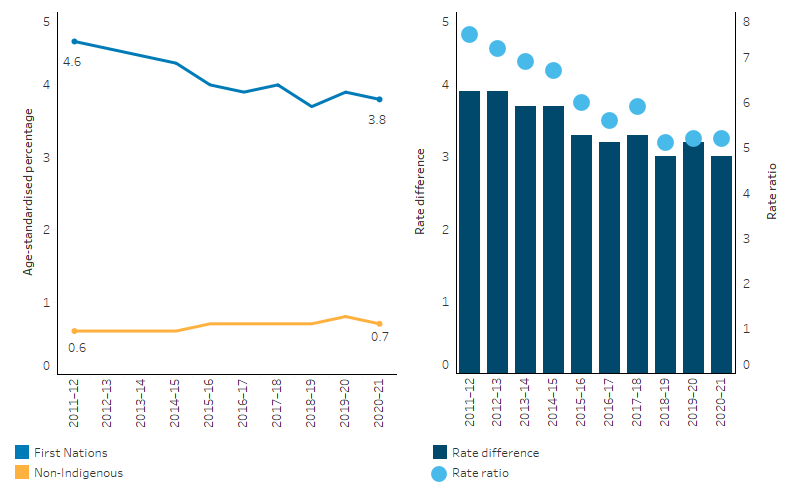

- The age-standardised proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk decreased from 4.6% to 3.8% between 2011–12 and 2020–21. The gap narrowed from a rate difference of 3.9 to 3.0 percentage points, and the rate ratio narrowed from 7.5 to 5.2.

- Of the 119,278 emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait to be seen or left at own risk, 63% (75,185) left prior to being attended by a medical professional and 37% (44,093) left after being attended but before the episode of treatment was completed.

- The proportion of emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait to be seen or left at own risk was higher for less urgent triage categories: 13.2% of all emergency department presentations triaged as non-urgent, compared with 11.7% for those triaged as semi-urgent, 7.7% for urgent, 4.0% for emergency, and 2.5% for resuscitation.

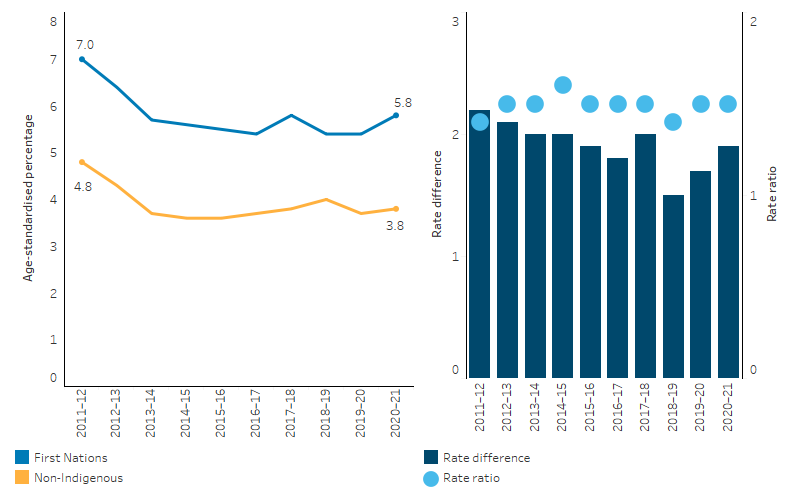

- Over the decade from 2011–12 to 2020–21, the age-standardised proportion of emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait to be seen by a health professional decreased from 7.0% to 5.8%, and the proportion for non-Indigenous Australians decreased from 4.8% to 3.8%. Based on linear regression analysis, the rate decreased by 0.1 percentage points annually for both First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians.

- The proportion of emergency department presentations where First Nations people left at own risk increased from 2.1% to 3.4%, while for non-Indigenous Australians it increased from 1.6% to 2.4%. Based on linear regression analysis, the age-standardised proportion for both First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians increased by 0.1 percentage points annually.

- A systematic review found that gaps in the quality of health care within the Australian health system are associated with self-discharge among First Nations people. The review findings suggest that reducing the occurrence of leave events requires better representation of First Nations people in the health workforce and working in partnership with First Nations people during the decision-making process to provide health services that meet the cultural needs of First Nations people.

- A study conducted at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney introduced the ‘Flexiclinic’ model, a flexible care approach co-designed with the Aboriginal Health Unit to improve care for First Nations patients and reduce did not wait to be seen and left at own risk rates. Within the first 3 months, this approach significantly reduced the combined rate of did not wait to be seen and left at own risk to 5.2% of presentations, a fivefold decrease in the probability of First Nations patients receiving incomplete care.

- Monitoring of cultural safety is limited by a lack of national and state-level data, particularly on the policies and practices of hospitals and other mainstream health services, and the experiences of First Nations patients in hospitals.

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people are more likely than non‑Indigenous Australians to leave hospital before discharge by their clinician. Patient experiences of health care services affect health-related behaviours and health outcomes. People who leave hospital before discharge are more likely to re-present to emergency departments and have higher mortality rates (Shaw 2016).

The measure reported here is based on the extent to which First Nations people ‘vote with their feet’, providing indirect evidence of the extent to which hospital services are responsive to the needs of First Nations patients.

The rates of First Nations hospital patients who leave prior to commencing or completing treatment is also used as an indirect measure of cultural safety in the AIHW’s Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework.

The outcomes of self-discharge from health services for First Nations people need to be understood in context. Patients self-discharge because of factors such as dissatisfaction with care, poor communication, long waiting times, and feeling better, in addition to external factors such as family and employment responsibilities. These factors, plus a lack of cultural safety, and interpersonal and institutional racism contribute to the disproportionately higher rates of First Nations people self-discharging from hospital (Askew et al. 2021).

Furthermore, colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and their culture. This history and the ongoing impacts of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and resulted in poorer outcomes for First Nations people. The Aboriginal community controlled health services sector plays a significant role to provide comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people (Panaretto et al. 2014).

Among mainstream health services, barriers for First Nations people in accessing care include racism, lack of cultural safety and lack of local cultural competency among staff, as well as cost, transport, poor communication pathways and poor service infrastructure. Person-centred care involves placing the experience of First Nations patients at the centre of determining responsive care so patients can determine their own health priorities and care pathways. This includes embedding trauma-aware and healing-informed approaches to care. Providing access to flexible, culturally safe and responsive acute care requires services to work with First Nations people and communities to understand their needs and to address the systemic factors that result in patients taking own leave or discharging against medical advice.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Improving the health system is a key focus of the Health Plan which includes:

- Priority 8: Identify and eliminate racism, including individual and institutional racism across health, disability and aged care systems.

- Priority 9: Access to person-centred and family-centred care, including making acute care settings accessible and culturally safe to address gaps such as those seen in surgery procedures and wait times, and in rates of discharge against medical advice

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

In this measure, data are presented for admitted patient hospitalisations, as well as for presentations to emergency departments.

Hospitalisations

Between July 2019 and June 2021, there were 26,985 hospitalisations (excluding dialysis) for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk. This equated to 4.0% of all hospitalisations for First Nations people. The proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk was higher for First Nations males than for First Nations females (4.4% and 3.7% of all hospitalisations, respectively) (Table D3.09.2).

Age-specific rates for discharge at own risk indicate that this measure is not strongly age-related. When making comparisons between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians (of all ages), this measure uses age-standardised rates; however, the corresponding crude rates can be found in the specified data tables.

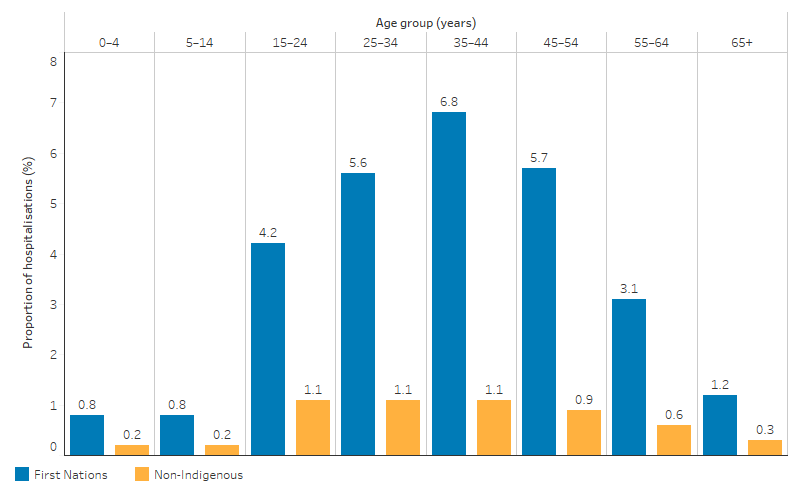

Between July 2019 and June 2021, the proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk for First Nations people was lowest for children aged 0–4 and 5–14 (both at 0.8% of all hospitalisations). The proportion increased to a peak of 6.8% for those aged 35–44 and decreased thereafter for those aged over 45, from 5.7% for those aged 45–54 to 1.2% for those aged 65 and over (Table D3.09.1, Figure 3.09.1).

The proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk was higher for First Nations people compared with non-Indigenous Australians in all age groups between July 2019 and June 2021. The largest relative difference, measured by ratio of the percentage of First Nations people to the percentage of non-Indigenous Australians, was among those aged 35–44, where the proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge for First Nations people was 6.4 times as high as that for non-Indigenous Australians (Figure 3.09.1).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the age-standardised proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk was 5.2 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.09.1).

Figure 3.09.1: Proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk (excluding dialysis), by Indigenous status and age group, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.09.1. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

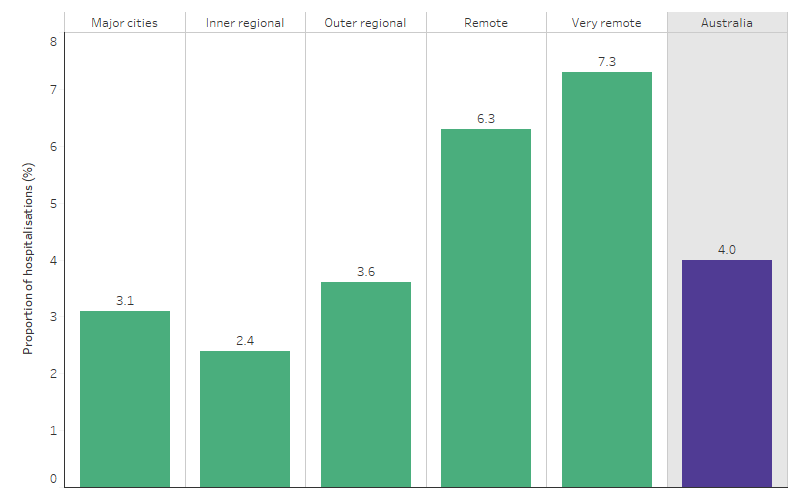

From July 2019 to June 2021, the proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended with discharge at own risk was generally higher in more remote areas, the exception being for those living in Inner regional areas where the proportion was lowest (2.4% or 3,415 hospitalisations). The proportion was highest for those living in Very remote areas of Australia (7.3% or 6,518 hospitalisations), followed by those in Remote areas (6.3% or 3,848 hospitalisations). In comparison, the proportions in non-remote areas ranged from 2.4% to 3.6% (Table D3.09.4, Figure 3.09.2).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk was higher for First Nations people than for non-Indigenous Australians across all remoteness areas. Age-standardised rates ranged from 3.3 times as high for First Nations people in Inner regional areas to 7.9 times as high for those in Very remote areas (Table D3.09.4).

Figure 3.09.2: Proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk (excluding dialysis) for First Nations people, by remoteness, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.09.4. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

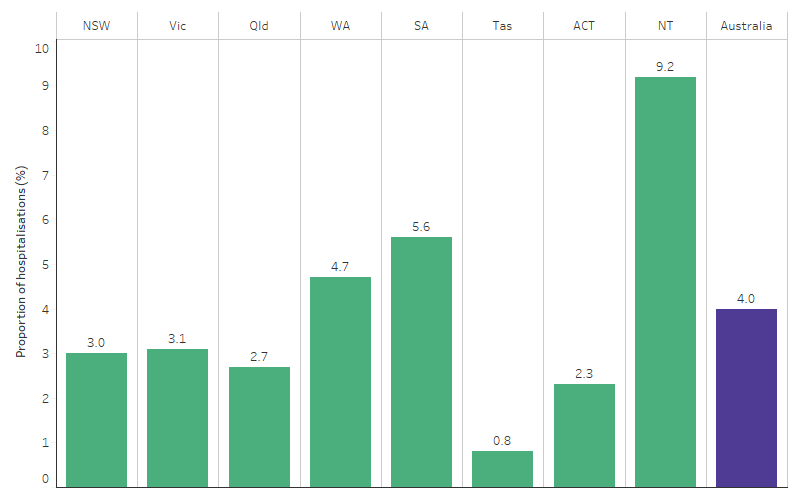

Over the period from July 2019 to June 2021, the proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended with discharge at own risk varied by state and territory, ranging from 0.8% of all hospitalisations (excluding dialysis) in Tasmania to 9.2% in the Northern Territory (Figure 3.09.3). For non-Indigenous Australians, the proportion ranged from 0.3% of all hospitalisations in Tasmania to 1.0% in the Northern Territory.

Across states and territories, and based on age-standardised rates, the gap between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians in the proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk ranged from 0.5 percentage points (in Tasmania) to 7.2 percentage points (in the Northern Territory) (Table D3.09.3).

Figure 3.09.3: Proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk for First Nations people, by jurisdiction, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.09.3. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Data on hospitalisations ending in discharge at own risk can be examined by principal diagnosis in 2 complementary ways:

- looking at data on all hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk, and dividing these into groups based on the principal diagnosis recorded for each of these hospitalisations. This shows the contribution of different diagnosis groups to the total number of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk. Note that this will be affected to some degree by the total number of hospitalisations for different diagnoses (see also measure 1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisations).

- looking at hospitalisations for each principal diagnosis category, and calculating the proportion of hospitalisations ending in discharge at own risk within each category. This can show the principal diagnosis groups where rates of discharge at own risk are higher or lower than average.

Of the 26,985 hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk, the leading principal diagnosis groups (excluding dialysis) were:

- injury and poisoning (19.2% or 5,190 hospitalisations)

- mental and behavioural disorders (9.7% or 2,626 hospitalisations)

- respiratory diseases (9.1% or 2,466 hospitalisations) (Table D3.09.7).

Note that this ranking excludes ‘symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified’ (3,088 hospitalisations or 11.4% of all hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk).

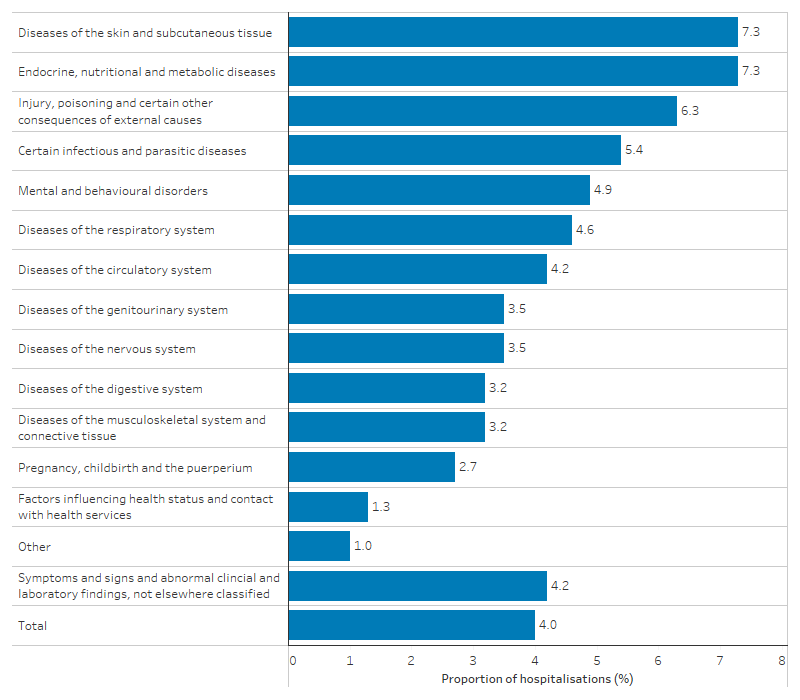

When the number of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk are expressed as the proportion of all hospitalisations for each principal diagnosis group, the rate of discharge at own risk for First Nations people was highest for diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (7.3% or 1,805 hospitalisations) and endocrine, nutritional and metabolic disorders (7.3% or 1,770 hospitalisations) followed by injury and poisoning (6.3% or 5,190 hospitalisations) (Table D3.09.7, Figure 3.09.4).

Figure 3.09.4: Proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk (excluding dialysis), by principal diagnosis group, Australia, July 2019 to June 2021

Note: Percentage of hospitalisation of each diagnosis group was calculated as the number of hospitalisations for the specified principal diagnosis that ended in discharge at own risk divided by the total number of hospitalisations for that principal diagnosis (excluding dialysis) and multiplied by 100.

Source: Table D3.09.7. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Emergency department presentations

Between July 2019 and June 2021, there were 119,278 emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the patient did not wait or left at own risk (9.4% of all emergency department presentations for First Nations people). This consisted of:

- 75,185 (63.0%) presentations where the patient did not wait to be seen by a healthcare professional (5.9% of all emergency department presentations for First Nations people)

- 44,093 (37.0%) presentations where the patient left at own risk without completing treatment, after being seen by a health care professional but before the episode was complete (3.5% of all emergency department presentations) (Table D3.09.11).

After adjusting for differences in the age-structure of the 2 populations, the proportion of emergency department presentations where the patient did not wait to be seen or left at own risk was 1.5 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.09.11).

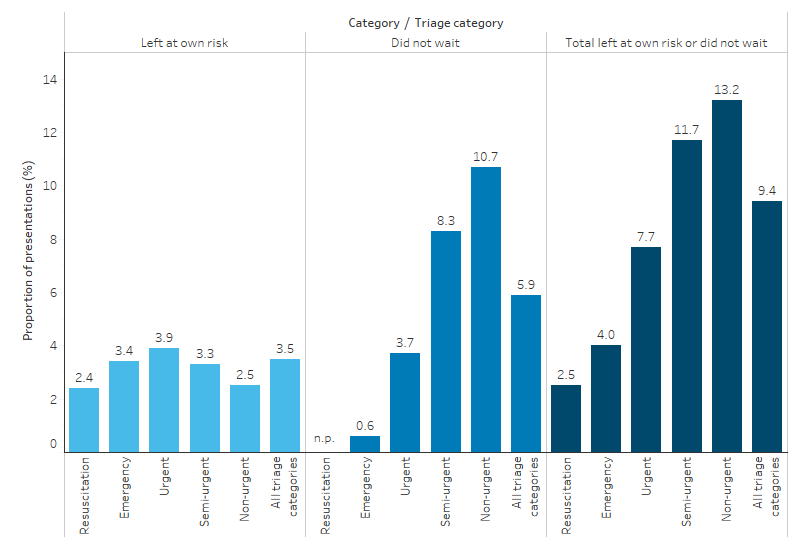

The proportion of emergency department presentations where the patient did not wait to be seen or left at own risk varied by triage category, with higher proportions among less urgent triage categories.

For First Nations people, the proportion of emergency department presentations where the person did not wait to be seen or left at own risk was:

- 13.2% (17,804 presentations) of all emergency department presentations triaged as non-urgent

- 11.7% (59,576) of presentations triaged as semi-urgent

- 7.7% (34,639) of presentations triaged as urgent

- 4.0% (6,555) of presentations triaged as emergency

- 2.5% (246) of presentations with a triage category of resuscitation.

This pattern was driven by presentations where the patient did not wait to be seen by a health care professional, rather than where the patient left at own risk. For example, First Nations patients did not wait to be seen for 10.7% of non-urgent presentations compared with 0.6% of emergency presentations. However, the rate at which First Nations patients left at own risk after being seen by a health care professional was relatively consistent across triage categories and was lower for presentations categorised as non-urgent (2.5%) compared with presentations categorised as an emergency (3.4%) (Table D3.09.11, Figure 3.09.5).

Figure 3.09.5: Proportion of public emergency department presentations where First Nations patients did not wait or left at own risk, by triage category, July 2019 to June 2021

n.p. not published

Source: Table D3.09.11. AIHW analysis of National Non-admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

From July 2019 to June 2021, by age group, the proportion of emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait to be seen or left at own risk was highest for those aged 25–34 (11.8% or 26,227 presentations), followed by those aged 35–44 (11.7% or 20,432 presentations) (Table D3.09.16).

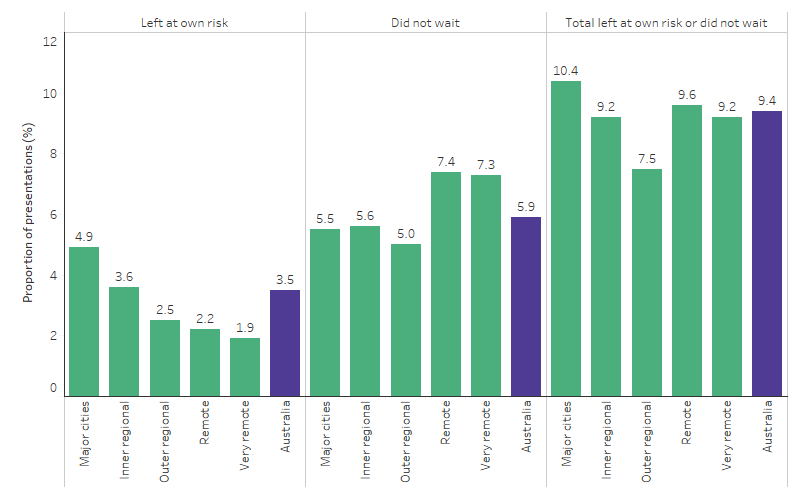

For First Nations people, the proportion of emergency department presentations where the person did not wait or left at own risk was highest for those living in Major cities (10.4%), and lowest for those living in Outer regional areas (7.5% or 19,521 presentations) (Table D3.09.13, Figure 3.09.6). Looking at presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait separately to those where they left at own risk:

- the proportion where the person did not wait was highest for First Nations people living in Remote areas (7.4%), followed by Very remote areas (7.3%), with rates between 5.0% and 5.6% in the 3 non-remote categories

- the proportion who left at own risk decreased with increasing remoteness area of usual residence – from 4.9% for First Nations people living in Major cities to 1.9% for those living in Very remote areas (Table D3.09.13).

Figure 3.09.6: Proportion of public emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the patient did not wait or left at own risk, by remoteness, July 2019 to June 2021

Source: Table D3.09.13. AIHW analysis of National Non-admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Between July 2019 and June 2021, across states and territories, the proportion of emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the person did not wait to be seen or left at own risk ranged from 5.8% of presentations in Tasmania (1,177) to 12.0% of presentations in Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory (9,544 and 1,362 presentations, respectively) (Table D3.09.14).

Changes over time

Age-standardised proportions are used in this section, to account for changes in the age-structure of the populations over time, as well as for differences in the age-structures of the First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australian populations. Crude proportions are available in the data tables.

There is some year-to-year variability in the data, so linear regression was used to examine trends, taking into consideration information from all years available, rather than only the first and last year in the series (see Statistical terms and methods).

The age-standardised proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk decreased from 4.6% in 2011–12 to 3.8% in 2020–21. Based on linear regression of all data points from 2011–12 to 2020–21, the age-standardised proportion of hospitalisations for First Nations people that ended in discharge at own risk decreased by 0.1 percentage points annually (Table D3.09.6, Figure 3.09.7). Reflecting improvements for First Nations people, between 2011–12 to 2020–21, the gap narrowed from a rate difference of 3.9 percentage points to 3.0 percentage points, and the rate ratio narrowed from 7.5 to 5.2.

Figure 3.09.7: Age-standardised proportion of hospitalisations that ended in discharge at own risk (excluding dialysis) and changes in the gap, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2011–12 to 2020–21

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people minus the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people divided by the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D3.09.6 AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Based on linear regression analysis, there was little change in the age-standardised proportion of public hospital emergency department presentations for First Nations people where the patient did not wait to be seen or left at own risk over the decade from 2011–12 to 2020–21, varying from year-to-year between 8.0% (in 2015–16) and 9.2% (in 2020–21). The age-standardised proportion for non-Indigenous Australians also changed little, ranging between 5.3% (in 2014–15) and 6.4% (2011–12) (Table D3.09.12).

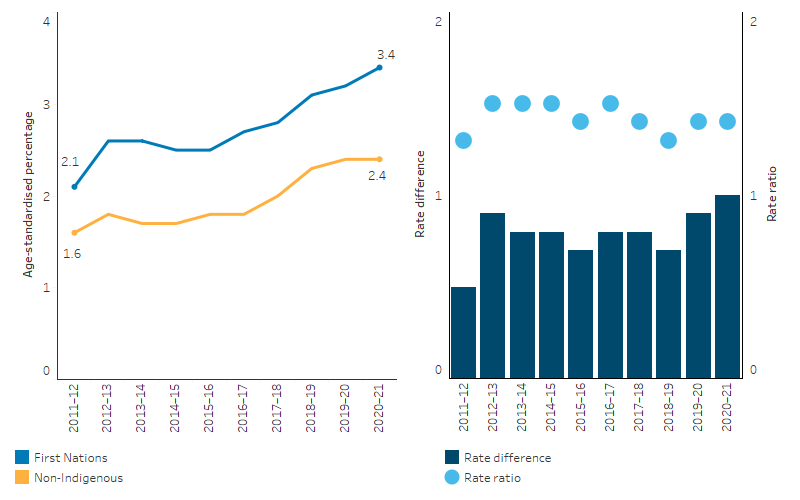

There were contrasting trends for presentations where the patient left at own risk compared with presentations where the patient did not wait to be seen. Over the decade from 2011–12 to 2020–21, the age-standardised proportion of public hospital emergency department presentations where First Nations people left at own risk increased from 2.1% to 3.4%. There was also an increase for non-Indigenous Australians, from 1.6% to 2.4% (Table D3.09.12, Figure 3.09.8). Based on linear regression analysis of all data points, the age-standardised rate for both First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians increased by 0.1 percentage points annually.

In contrast, the proportion of public hospital emergency department presentations where First Nations people did not wait to be seen by a health professional decreased from 7.0% to 5.8% (a decrease of 0.1 percentage points annually based on linear regression analysis), and the proportion for non-Indigenous Australians decreased from 4.8% to 3.8% (also a decrease of 0.1 percentage points annually based on linear regression analysis) (Table D3.09.12, Figure 3.09.9).

Figure 3.09.8: Age-standardised proportion of public hospital emergency department presentations where the patient left at own risk, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2011–12 to 2020–21

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people minus the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people divided by the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D3.09.12. AIHW analysis of National Non-admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Figure 3.09.9: Age-standardised proportion of public hospital emergency department presentations where the patient did not wait, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2011–12 to 2020–21

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people minus the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised percentage for First Nations people divided by the age-standardised percentage for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D3.09.12. AIHW analysis of National Non-admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database and ABS population estimates and projections (ABS 2019a, 2019b, 2022a, 2022b) for calculation of rates.

Research and evaluation findings

A systematic review examined the causes that contribute to discharge against medical advice and ‘take own leave’ events (ACSQHC 2020). The review found repeated themes, including systematic and personal racism, distrust of hospitals and patients feeling misunderstood and unwelcome. A lack of cultural competency, cultural safety in hospitals and health workforce cultural training were also recurrent themes. Another systematic review found that gaps in the quality of health care within the Australian health system are associated with leave events among First Nations people. The review findings suggest that reducing the occurrence of leave events requires better representation of First Nations people in the health workforce and working in partnership with First Nations people during the decision-making process to provide health services that meet First Nations cultural needs (Coombes et al. 2022).

A Western Australian study used linked data to explore the determinants of discharge against medical advice among patients experiencing their first in-patient admission for ischaemic heart disease (Katzenellenbogen et al. 2013). One of the findings of this study was that the odds of dismissal against medical advice was not associated with the severity of the event, unlike for non-Indigenous patients.

Between 2016 and 2020, a study of First Nations patients in an Australian emergency department found that of 6,446 presentations, 87% waited to be seen, while 13% left without completing treatment. Patients assigned to a lower triage category were significantly more likely to leave, suggesting potential underestimation of illness severity during the triage process for this group. Homelessness and lack of private health insurance were also predictors for leaving the Emergency Department. Additionally, patients with behavioural alerts were 1.6 times more likely to leave, indicating potential issues with communication or perceived treatment by the Emergency Department staff. Behavioural alerts are markers on patient records indicating prior instances of perceived threatening behaviour, intended to ensure staff safety. The study identified the need for a social determinants of health lens and trauma informed care approach as best practice in Emergency Department care for First Nations patients (Hutton et al. 2023).

A cohort study in Western Australian First Nations children aged 0–4 years from 2002 to 2018 examined the associations between discharge against medical advice for hospital admissions and Emergency Department presentations, and: (i) child, family and episode of service characteristics, (ii) the odds of 30-day readmission/re-presentation for First Nations children aged <5 years born in Western Australia between 2002 and 2013. Discharge against medical advice was associated with a range of characteristics, including hospital location, mode of admission/triage code and year of admission/presentation. Between 2014 and 2018, the adjusted odds of discharge against medical advice decreased by 75% compared to the period between 2002 and 2005. This reduction was potentially driven by improvements in regional and remote hospitals. Although hospital admissions in regional and remote hospitals had almost 7 times the adjusted risks of hospital admissions in Perth metropolitan hospitals, by 2018 the gap between regional and remote hospitals and Perth had diminished. The adjusted risks of Emergency Department discharge against medical advice decreased by 12% for presentations in regional and remote hospitals compared to those in Perth metropolitan hospitals. However, there was also a higher frequency of less urgent presentations to regional and remote Emergency Departments compared with Perth. This suggests that more primary healthcare services are needed in regional and remote areas. There was no evidence of hospital discharge against medical advice being associated with an increased likelihood of hospital readmission within 30 days and limited evidence of Emergency Department discharge against medical advice being associated with re-presenting to an Emergency Department within 30 days. The study suggests further work is needed to reduce discharge against medical advice for episodes associated with less urgent entry to hospital and Emergency Departments (Christensen et al. 2023).

Impact of First Nations health workers

Aboriginal Health Workers and Liaison Officers (AHWLOs) are a unique workforce introduced to increase access to culturally safe care and, ultimately, help to address health inequities experienced by First Nations people. A systematic review found that AHWLOs improve communication between patients and medical staff, improve continuity of care and reduce patient discharge against medical advice (Mackean et al. 2020).

A retrospective study was conducted to understand the impact of introducing Aboriginal Liaison Officers (ALO) into an Orthopaedic multi-disciplinary team on the self-discharge rates of First Nations orthopaedic patients. The analysis of case-notes of patients admitted to the Orthopaedic unit at Alice Springs Hospital found that the inclusion of ALOs led to a notable 37% reduction in self-discharge rates among First Nations patients. Furthermore, fewer patients left before receiving their definitive surgical and medical treatments or before completing their postoperative intravenous antibiotic regimen. Risk factors for self-discharge included being younger, unemployed or pensioners, residing in specific areas near Alice Springs, and having certain medical conditions. The study concluded that the routine inclusion of ALOs in the Orthopaedic team significantly decreased the risk of self-discharge among First Nations patients, ensuring that they received critical aspects of their care before leaving the hospital (Cheok et al. 2023).

First Nations patient experiences

A study explored the reasons behind self-discharge from health services, focusing on the experiences of First Nations people. The research found that while both First Nations and non-Indigenous participants had similar unmet needs during their hospital stays, the negative impact of these unmet needs was intensified for First Nations individuals due to experiences of racism and discrimination. First Nations participants reported a lack of cultural safety, feelings of isolation, mistrust in the health system, and encounters with institutional racism. The study underscores the importance of respectful, empathetic, and person-centred care to address these issues. For First Nations people, the lingering effects of colonisation manifest in daily experiences of interpersonal and institutional racism, making their hospital experiences more challenging and leading to a higher likelihood of self-discharge (Askew et al. 2021).

Another study explored the patient experience of the Better Cardiac Care (BCC) model at a Brisbane tertiary hospital’s cardiac unit for First Nations people. Conducted between November 2019 and September 2021, the research used a narrative methodology, gathering insights from 16 First Nations patients and 2 family members from south-eastern Queensland. It aimed to determine the acceptability, appropriateness, and areas of improvement of the BCC model from the perspectives of patients and their families. The sense of cultural connectedness and relationship between patients and the staff, especially First Nations staff, meant patients were empowered in the hospital structure. First Nations staff provided a social and cultural anchor for patients and recognised the contextual and structural challenges faced by patients including interpersonal and institutional racism within healthcare settings. This knowledge then helped the broader BCC staff to advocate and support patients holistically across the patient journey, even beyond hospital discharge. While patient-participants felt supported, family member-participants expressed a need for more emotional support, improved communication, and additional information during the admission and post-discharge rehabilitation period. The study concluded that empowering and employing First Nations staff and viewing patients holistically improved outcomes and met the needs of First Nations patients. The broader health system could benefit from valuing First Nations discourses on ‘relationality’ (Jennings et al. 2023).

Improving health services

A study was conducted at St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney and aimed to address the high rates of 'did not wait to be seen' and 'left at own risk' among First Nations patients in the Emergency Department. The study introduced the 'Flexiclinic' model, a flexible care approach co-designed with the Aboriginal Health Unit to improve care for First Nations patients and reduce did not wait to be seen and left at own risk rates. The Flexiclinic model was introduced in June 2020, and within the first 3 months, this approach significantly reduced the combined rate of did not wait to be seen and left at own risk to 5.2% of presentations, a fivefold decrease in the probability of First Nations patients receiving incomplete care. The Flexiclinic model was well received by both staff and patients and had no adverse effects on the delivery of services to other patient groups. The study concluded that the Flexiclinic approach significantly improved medical care for First Nations patients at St Vincent’s Hospital Emergency Department (Preisz et al. 2022).

The Department of Health of Western Australia undertook a review into ‘take own leave’, which refers to instances in which a patient chooses to leave prior to commencing or completing treatment, and includes discharge against medical advice (Aboriginal Health Policy Directorate 2018). The published paper is intended as a resource to assist health service providers and other stakeholders to address ‘take own leave’. Recommendations from the review covered a range of strategies across areas, including cultural competency; consultation, engagement and partnerships; communication and language; culturally safe hospital environments; the First Nations workforce; the social determinants of health; alcohol and other drugs; mental health; and use of technology. The review also identified existing Western Australian strategies and programs, including the Aboriginal Interpreting WA Kimberley pilot program; essential items packs for sudden admission patients; nicotine replacement therapy; and the Friends of Royal Perth Hospital volunteer group who assist with connecting with families and assisting with meeting responsibilities like washing and shopping.

A study of the use of Aboriginal interpreters in the Northern Territory found a low rate of interpreter bookings, a declining rate of completed interpreter bookings, and process barriers identified by staff, including booking complexities, time constraints, inadequate delivery of tools and training, and greater convenience of unofficial interpreters (Ralph et al. 2017). Royal Darwin Hospital introduced a package of measures comprising employment of a First Nations interpreter coordinator, training for health care providers in working with First Nations interpreters, and promoting the use of interpreters. An initial evaluation of this intervention found that it was associated with an immediate increase in interpreter bookings and a decline in First Nations patient self-discharge numbers (The Communicate Study group 2020).

The South Western Sydney Local Health District is cited as a good practice example of having strategies to improve its workforce’s cultural awareness and cultural competency to meet the needs of First Nations patients (ACSQHC 2017). Actions taken included the establishment of a cultural awareness framework, conducting mandatory online and face-to-face cultural awareness training for its workforce and undertaking an independent evaluation of the training’s effectiveness, and progressing an Aboriginal Workforce Strategy. The Aboriginal Cultural Training Framework: Respecting the Difference (the Framework) aimed to assist with increasing cultural competencies and promote greater understanding of the processes and protocols for delivering health services to First Nations people. An evaluation of the Framework found that its implementation target of having 80% of all health staff complete the training by the end of 2015 was challenging due to the significant cost and human resource implications, and the difficulty in ensuring a high level of First Nations community involvement (e.g. local Elders) in delivery. Respecting the Difference training requires a high level of personal engagement from participants, trainers and community representatives. It requires participants to question their attitudes and beliefs. The training challenges teams to critically evaluate how they engage with First Nations people and communities and to apply their learning in the workplace to better meet the needs of First Nations clients and ultimately improve outcomes (NSW Health 2013).

A 2022 essay argued for structuring hospital care to align with First Nations cultural values and needs, aiming to bridge the health disparities faced by First Nations people and highlighting the alienating nature of hospital environments for First Nations patients. Using Foucault’s concept of enunciative modalities and Bamblett’s theory of deficit discourses, the authors believe architecture perpetuates these disparities. Foucault’s concept scrutinises the power dynamics in health discourse, highlighting how authority is often linked to professional and educational status, as well as institutional context, which can amplify or marginalise certain voices and influence health policies and practices. Bamblett’s theory of deficit discourses critiques the focus on gaps and disadvantages in First Nations communities, contrasting it with First Nations knowledge systems rooted in relational networks and storytelling. Recognising power imbalances, the authors argued for reconfiguring hospitals to honour First Nations norms through architectural and systemic changes. Two national projects are exploring modifications to make hospitals more culturally attuned to First Nations patients’ needs, with one in Queensland and the other in Victoria. While these changes can enhance the environment, deeper systemic shifts are essential. Challenges faced by Aboriginal Liaison Units (ALUs), such as underfunding and complex reporting structures, highlight the need for institutional reforms to support First Nations patients. The authors propose a new First Nations-led typology to mediate hospital care, termed a ‘holding place’, which offers spatial, temporal, discursive, and relational practices. This typology emphasises the importance of integrating cultural practices and placing First Nations Elders at the centre of health care for First Nations individuals. This requires a systemic, holistic approach that recognises the strengths and resilience of First Nations communities, rather than focusing on deficits (McGaw et al. 2022).

Implications

The elevated levels of self-discharge from hospital suggest that there are significant issues in the responsiveness of hospitals to the needs and perceptions of First Nations people (see measure 3.08 Cultural competency). Mechanisms for obtaining feedback from First Nations patients will assist in responding and planning in relation to the rate of self-discharge. The data suggest these issues are important for all age groups, although the issues are most evident for those aged 15–54 years.

One aspect that is not clear from a simple analysis of hospital data on self-discharge by diagnosis is the degree of clinical risk to the patient due to discharging against medical advice. This risk may vary considerably depending on the severity of the diagnosis, and thus the ranking of diagnosis groups may not be the most clinically meaningful way of identifying areas for improvement. A deeper understanding of risks to the patient may assist hospital services in targeting efforts with regard to culturally safe communication strategies with patients, follow-up care after discharge and communication with health practitioners, notwithstanding the overall need for systemic improvements for culturally safe services.

There are several questions that health service researchers and health service managers need to tackle in devising strategies to achieve more responsive and respectful service delivery. More needs to be known about the reasons for the high rate of self-discharge across individual factors (such as personal circumstances, health and wellbeing and cultural issues); community-level factors (such as levels of trust or mistrust in the health system, and the availability of primary healthcare services); and hospital-level factors (such as staff attitudes, hospital policies and hospital design). Historical issues, such as segregation, and hospitals being seen as a place to go to die, are also factors to be investigated. Hospitals and health services that have implemented successful programs to reduce self-discharge need to be studied, and lessons disseminated.

The Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council funded work to develop a national framework to address critical contributing and protective factors to reduce the rate of First Nations people taking their own leave and discharging against medical advice from Australian hospitals. This includes addressing factors that affect access to hospital services by First Nations people, developing consumer-centred approaches that improve the health journey and the hospital environment, and improving the capability of hospitals to deliver culturally safe care for First Nations people. The framework recommends that conventional thinking focused on the actions of the patient must be turned on its head, with person-centred care seeking to shape health care around a person’s full range of needs and wants as a core principle in preventing and reducing ‘take own leave’ (National Take Own Leave Working Group 2017).

A significant body of work over the past 2 decades has sought to raise awareness and embed concepts of cultural respect in the Australian health system that are fundamental to improving access to quality and effective health care and improving health outcomes for First Nations people. There has been a longstanding commitment by Australian governments to enable this. The Cultural Respect Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2016–2026: A National Approach to Building a Culturally Respectful Health System plays a key role in reaffirming this commitment and provides a nationally consistent approach (AHMAC 2017). The National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards User Guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health recommends that health service organisations use the Cultural Respect Framework to develop, implement and evaluate cultural awareness and cultural competency strategies (ACSQHC 2017). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework plays a role in monitoring the commitment to embed cultural respect principles into the Australian health system.

Monitoring is also supported by the Cultural Safety in Health Care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring Framework which covers 3 domains: how health care services are provided, First Nations patients’ experience of health care and measures regarding access to health care (AIHW 2022). However, monitoring is limited by a lack of national and state-level data, particularly on the policies and practices of mainstream health services such as hospitals, and the experiences of First Nations patients in hospitals (AIHW 2022).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), released in December 2021, recognises that acute care settings must be accessible, culturally safe and responsive to address the gaps between First Nations people and non-Indigenous Australians’ experiences in hospitals, including the gap in surgery procedures and wait times, and the rates of early discharge or discharge against medical advice. Addressing these gaps will require hospitals to implement strategies to better deliver holistic, culturally safe and responsive models of care by improving employment of traditional health workers to provide complementary care and having care coordination pathways with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to deliver care on Country. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) addresses key challenges faced by the sector and proposes 17 transformative actions to fortify it. The overarching goal of the Health-SSP is to bolster a robust community-controlled sector, emphasising the importance of a collaborative approach between the sector and governments.

The Health Plan is aligned with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan 2021–2031 (the National Workforce Plan), which aims to increase representation of First Nations people in all health roles and locations across Australia. It sets an ambitious target: for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to represent 3.43% of the national health workforce by 2031. The National Workforce Plan commits governments to work in partnership with First Nations people to meet this target and to foster a culturally safe and responsive health system.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- Aboriginal Health Policy Directorate 2018. Aboriginal Patient Take Own Leave. Review and recommendations for improvement. Perth.

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019a. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2019b. Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 - 2031. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2022a. National, state and territory population, March 2022. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS 2022b. National, state and territory population, Reference Period December 2022. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ACSQHC (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care) 2017. National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards User Guide for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health. Sydney.

- ACSQHC 2020. Understanding leave events for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and other Australians from health service organisations Systematic Literature Review. Sydney.

- AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2017. Cultural Respect Framework 2016-2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Vol. 17 (ed., Council of Australian Governments). Canberra: AHMAC.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2022. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra.

- Askew DA, Foley W, Kirk C & Williamson D 2021. “I’m outta here!”: a qualitative investigation into why Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people self-discharge from hospital. BMC health services research 907.

- Cheok T, Berman M, Delaney-Bindahneem R, Jennings MP, Bray L, Jaarsma R et al. 2023. Closing the health gap in Central Australia: reduction in Indigenous Australian inpatient self-discharge rates following routine collaboration with Aboriginal Health Workers. BMC health services research 874.

- Christensen D, Gibberd A, McNamara B, Eades S, Shepherd C, Preen DB et al. 2023. Hospital and emergency department discharge against medical advice in Western Australian Aboriginal children aged 0–4 years from 2002 to 2018: A cohort study. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 37:691-703.

- Coombes J, Hunter K, Bennett-Brook K, Porykali B, Ryder C, Banks M et al. 2022. Leave events among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 22:1488.

- Hutton J, Gunatillake T, Barnes D, Phillips G, Maplesden J, Chan A et al. 2023. Characteristics of First Nations patients who take their own leave from an inner‐city emergency department, 2016–2020. Emergency medicine Australasia 35:74-81.

- Jennings W, Egert S, Fisher C, Renouf S, Bryce V, Grugan S et al. 2023. Better cardiac care - the patient experience - a qualitative study. International Journal for Equity in Health 22:122.

- Katzenellenbogen JM, Sanfilippo FM, Hobbs MS, Knuiman MW, Bessarab D, Durey A et al. 2013. Voting with their feet-predictors of discharge against medical advice in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal ischaemic heart disease inpatients in Western Australia: an analytic study using data linkage. BMC health services research 13:330.

- Mackean T, Withall E, Dwyer J & Wilson A 2020. Role of Aboriginal Health Workers and Liaison Officers in quality care in the Australian acute care setting: a systematic review. Australian Health Review 44:427-33.

- McGaw J, Vance A & Patten H 2022. A ‘Holding Place’: An Indigenous Typology to Mediate Hospital Care. Journal of Architectural Education 76:75-84.

- National Take Own Leave Working Group 2017. A National Framework to Reduce Taken Own Leave Events Among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients.

- NSW Health 2013. The Aboriginal Cultural Training Framework: Respecting the Difference Implementation, Process Evaluation Report - 2013. NSW Health. Viewed.

- Panaretto K, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring I 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

- Preisz P, Preisz A, Daley S & Jazayeri F 2022. 'Dalarinji': A flexible clinic, belonging to and for the Aboriginal people, in an Australian emergency department. Emergency medicine Australasia 34:46-51.