Key messages

- The 2021 Census of Population and Housing shows that 3.1% (16,659) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 and over were employed in health-related occupations in 2021. Females accounted for 78% of Indigenous Australians employed in health-related occupations.

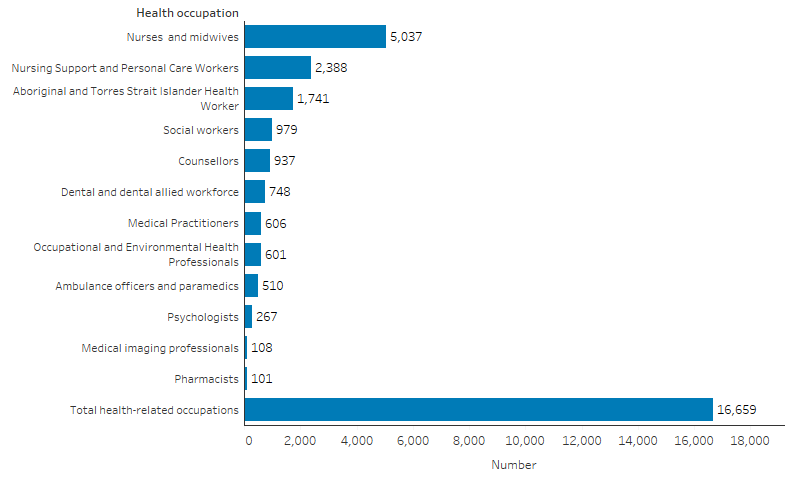

- The health-related occupations with the largest number of Indigenous employees aged 15 and over in 2021 were nurses and midwives (5,037), followed by nursing support and personal care workers (2,388), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers (1,741).

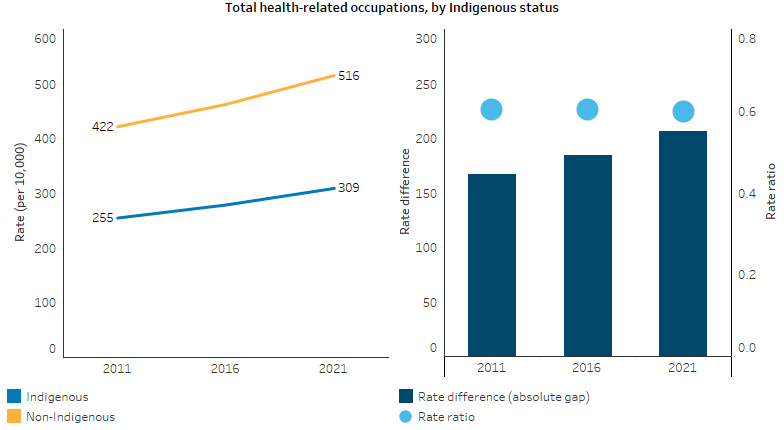

- In 2021, Indigenous Australians worked in health-related occupations at about 60% of the rate of non-Indigenous Australians – 309 compared with 516 per 10,000 population respectively. Across the states and territories, the absolute difference was highest in the Northern Territory, (166 compared with 742 per 10,000).

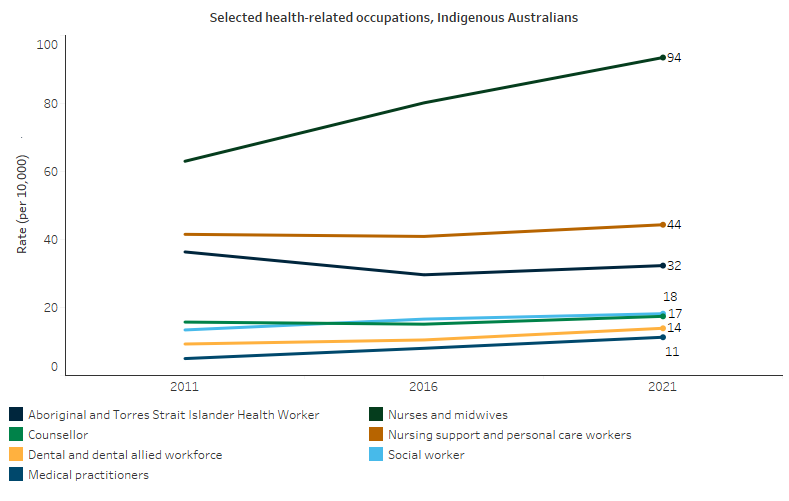

- Between 2011 and 2021, the rate of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations increased from 255 to 309 per 10,000 population, with increased numbers of nurses and midwives accounting for 54% of this increase. However, relative to population size, Indigenous Australians were employed in health-related occupations at about 60% the rate of non-Indigenous Australians in 2021 (rate ratio 0.6).

- In 2021, based on data on registered health professionals from the National Health Workforce, Indigenous Australians were employed in registered health professions at a rate that was about one-third that of non-Indigenous Australians – 89 compared with 267 per 10,000 population aged 15 and over respectively. Across the 16 registered health professions, the absolute gap in rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians were largest among nurses and midwives (rate difference of 87 per 10,000) and medical practitioners (37 per 10,000 population).

- Of Indigenous Australians employed in registered health professions in 2021 (7,844), 65% were a nurse and/or midwife (5,135), 26% an allied health professional (2,017), 7% a medical practitioner (563), and 1.6% as a dental practitioner (129).

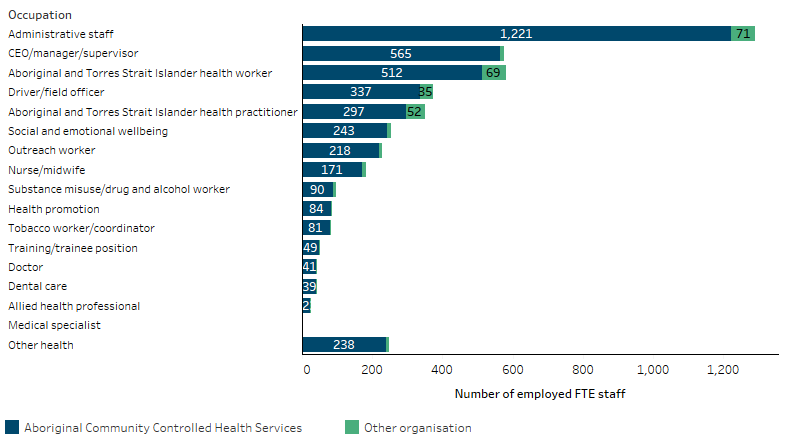

- Indigenous Australians made up 51% (4,499) of the employed full-time equivalent workforce in Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health-care organisations in 2021–22. Of these, 4,208 (94%) were employed at ACCHSs.

- Research has shown that Indigenous health staff appeared to sustain better connection, rapport and trust with Indigenous patients and reduce their anxiety and enhance communication. There is evidence to suggest that Indigenous health workers may help to improve attendance at appointments, acceptance of treatment and assessment recommendations, reduce discharge against medical advice, increase patient contact time, enhance referrals and improve follow.

- Aboriginal Medical Services (AMS) provide a culturally appropriate alternative to mainstream health services that can improve service uptake. Participants in a Brisbane study of government-controlled AMS and ACCHS reported marked health improvements in their communities due to the establishment of these services, and their important role in addressing the negative effects of discrimination on health.

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are significantly under-represented in the health workforce. This under-representation potentially contributes to reduced access to health services for the broader Indigenous Australian population. The accessibility of a health service goes beyond its physical availability and also encompasses other aspects, such as whether it is culturally safe (Scrimgeour & Scrimgeour 2008). The provision of culturally safe care is essential to meet the health care needs of Indigenous Australians effectively and requires health professionals to have considered power relations, cultural differences and patients’ rights (AHMAC 2016). Culturally safe health care includes the provision of services underpinned by Indigenous Australians’ beliefs and values (AH&MRC 2015). Recognition and understanding of the diversity of Indigenous cultures and regional variations is also vital to providing culturally safe care (Scrimgeour & Scrimgeour 2008). A key feature of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) is the provision of culturally safe care, and research has found the ACCHS sector to be a leading employer of Indigenous Australians (Campbell et al. 2018).

The Indigenous workforce is integral to ensuring that the health system can address the needs of Indigenous Australians. Indigenous health professionals can align their unique technical and sociocultural skills to improve patient care, improve access to services and support the provision of culturally appropriate care in the services that they and their non-Indigenous colleagues deliver (Anderson et al. 2009; West et al. 2010). While the Indigenous workforce plays an important role in the provision of culturally appropriate services, it is the responsibility of the health-care system to ensure that mainstream health services are culturally competent through high quality professional development and training, appropriate management where cultural respect is lacking, and staff developing awareness of their own unconscious bias (AHMAC 2016).

International studies have found that people prefer seeing health professionals from the same ethnic background and that improved health outcomes can result (LaVeist et al. 2003; Powe & Cooper 2004). Australian research has shown that Indigenous Australians want their health care to include Indigenous staff and clinicians (Lai et al. 2018). There can be a preference among Indigenous Australians for care by Indigenous health professionals, and qualitative research has shown that Indigenous health staff appeared to sustain better connection, rapport and trust with Indigenous patients (de Witt et al. 2018; Hayman N.E. et al. 2009) and reduce their anxiety and enhance communication (Freeman et al. 2014). There is evidence to suggest that Indigenous health workers may help to improve attendance at appointments, acceptance of treatment and assessment recommendations, reduce discharge against medical advice, increase patient contact time, enhance referrals and improve follow up (Jongen et al. 2019).

Data findings

Health-related workforce

An analysis of the 2021 Census of Population and Housing (Census) indicates that there were 16,659 Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations – 3.1% of the Indigenous population aged 15 and over (excluding those who did not state their occupation) (Table D3.12.13).

The health-related occupations with the largest number of Indigenous employees aged 15 and over were nurses and midwives (5,037, or 94 per 10,000 population), followed by nursing support and personal care workers (2,388, or 41 per 10,000), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers (32 per 10,000, or 1,741) (Table D3.12.12, Figure 3.12.1).

Figure 3.12.1: Number of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations, Australia, 2021

Note: Total health-related occupations include occupations not shown separately in the figure. See Table D3.12.12 for additional data.

Source: Table D3.12.12, AIHW analysis of 2021 Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

Based on 2021 Census data, of the 16,659 Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations, 4,588 were aged 25–34 (28% of Indigenous Australians in the health-related workforce), 3,476 were aged 45–54 (21%), and 3,442 were aged 25–34 (21%). Females accounted for 78% of Indigenous Australians employed in health-related occupations (Table D3.12.14).

Across states and territories, the rate of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in the health workforce ranged from 166 per 10,000 population in the Northern Territory to 374 per 10,000 in Victoria (Table D3.12.13).

Indigenous-specific primary health care services workforce

For Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations, Indigenous Australians made up 51% (4,499) of the workforce as at June 2022 (excluding visiting staff).

Of the 4,499 full-time equivalent (FTE) Indigenous staff, 4,208 (94%) were employed at ACCHSs. The occupation with the highest FTE number of Indigenous staff was administrative staff (1,291) (Table D3.12.15, Figure 3.12.2).

Figure 3.12.2: Number of Indigenous FTE staff employed by Commonwealth-funded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care organisations, by organisation type, 2021–22

Source: Table D3.12.15. AIHW analyses of Online Services Report data collection, 2021–22.

Of all FTE staff in Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations in 2021–2022, the number of FTE staff who were Indigenous was highest in Outer regional areas (58% of all staff) (AIHW 2023).

The proportion of staff in all Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations who were Indigenous was highest for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners (99.7%) and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers (99.5%). An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker includes a person with a minimum qualification in the field of primary health-care work or clinical practice. An Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner is a person who has completed a Certificate IV in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care (Practice) and is registered with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practice Board of Australia.

The professions with the lowest proportion of Indigenous staff were for medical specialists (2.1%), followed by doctors (6.1%), allied health professionals (7.9%), and nurses and midwives (15%) (Table D3.12.15).

Registered health professionals

The National Registration and Accreditation Scheme regulates 16 health professions across Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners, Chinese Medicine Practitioners, Chiropractors, Dental Practitioners, Medical Practitioners, Medical Radiation Practitioners, Nurses, Midwives, Occupational therapists, Optometrists, Osteopaths, Paramedics, Pharmacists, Physiotherapists, Podiatrists, and Psychologists (AHPRA 2022). People may be registered in more than one health profession.

The National Health Workforce Data Set contains data on these registered health professionals. It shows that in 2021 there were 9,274 Indigenous Australians registered as health professionals. This included 792 registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners, of which 639 of them were practicing in their profession (Table D3.12.1).

In 2021, of the 9,274 Indigenous Australians registered as health professionals, 7,844 were employed in their registered profession. Of those employed (7,844), 65% were employed as a nurse and/or midwife (5,135), 26% as an allied health professional (2,017), 7% as a medical practitioner (563), and 1.6% as a dental practitioner (129) (Table D3.12.1).

Among Indigenous Australians employed in the allied health registered professions, the most common occupation was Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners (639 Indigenous Australians), followed by paramedics (350), psychologists (267), and physiotherapists (251).

Females accounted for 81% of all registered Indigenous health professionals employed in their registered profession. Indigenous females accounted for the majority of employed Indigenous health professionals across most registered professions, with particularly high proportions of females among nurses and midwives (90%) and occupational therapists (89%). In contrast, among registered and employed Indigenous paramedics, over half (54%) were males (Table D3.12.2).

The rate of Indigenous Australians working in registered health professions was highest for those aged 35–44 and 45–54 (2,028 and 1,951 per 100,000 population, respectively) and lower for those aged 55–64 (1,827 per 100,000) and those aged 20–34 (1,333 per 100,000) (Table D3.12.3).

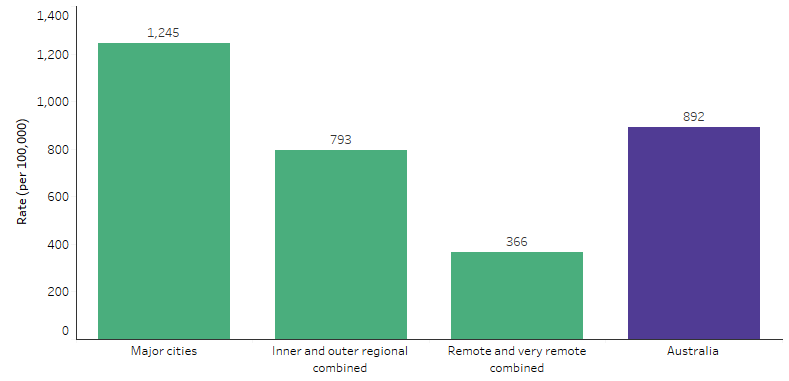

The rate of Indigenous Australians working in registered health professions was lower in regional and remote areas than in cities. In 2021, among Indigenous Australians, there were 1,245 registered and employed health professionals per 100,000 population in Major cities, compared with 793 per 100,000 in Inner and Outer regional areas combined, and 366 per 100,000 in Remote and very remote areas combined (Table D3.12.5, Figure 3.12.3).

Figure 3.12.3: Rate of Indigenous Australians employed in registered health professions, by remoteness area, 2021

Source: Table D3.12.5. AIHW analysis of National Health Workforce Data Set.

Comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians are under-represented in the health workforce.

In 2021, Indigenous Australians accounted for 1.7% of all Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations, based on self-reported data from the ABS 2021 Census of Population and Housing (proportion excludes people for whom Indigenous status was not stated) (Table D3.12.14). Note that data from the ABS Census capture a wider range of health-related occupations than are included in the National Health Workforce Data Set, including those not requiring professional registration, for example, dental assistants, nursing and personal support workers, and health service managers such as Nursing Clinical Directors.

Relative to population size, Indigenous Australians were employed in health-related occupations at about 60% the rate of non-Indigenous Australians in 2021. For every 10,000 individuals aged 15 and over, there were 309 Indigenous workers in health care, compared with 516 non-Indigenous workers (Table D3.12.13). Across states and territories, the difference in the rate was highest in the Northern Territory, where the rate for Indigenous Australians was about one-fifth (22%) that of non-Indigenous Australians (166 compared with 742 per 10,000 population). New South Wales and Victoria had the smallest differences, with rates of 344 and 374 per 10,000 Indigenous Australians respectively, compared with 478 and 522 for non-Indigenous Australians.

The specific health-related occupations with the largest absolute gap in representation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians nationally are registered nurses and general practitioners, with differences of 73 and 20 per 10,000 population respectively (Table D3.12.12).

The National Health Workforce Data Set provides information on registered health professionals. Based on these data, 1.2% of registered health professionals employed in their registered profession identified as being Indigenous Australians - 7,844 of 670,416 (Table D3.12.1). Aside from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners, which are roles only open to Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people (100% Indigenous), the proportion of Indigenous Australians was highest among enrolled nurses (2.7%), and paramedics (1.9%). Note, both registered and enrolled nurses need to be registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA), however registered nurses typically complete a higher education and training qualification and have a broader and more autonomous scope of practice compared with enrolled nurses, so are reported separately.

Relative to population size, in 2021, Indigenous Australians were employed in registered health professions at a rate that was about one-third that of non-Indigenous Australians – 89 compared with 267 per 10,000 population respectively (Table D3.12.1). Across the health professions regulated under the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme, the largest absolute gap in rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was among nurses and midwives (rate difference of 87 per 10,000 population), followed by medical practitioners (37 per 10,000). Among nurses and midwives, the difference was larger for registered nurses (rate difference of 82 per 10,000 population) than for enrolled nurses (4.7 per 10,000) or midwives (5.9 per 10,000). Among registered medical practitioners, the difference was largest for specialists (rate difference of 15 per 10,000 population), followed by general practitioners (11 per 10,000).

Changes over time

Based on Census data, between 2011 and 2021, the number of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations increased from about 8,800 to about 16,700 people. As a population rate, for Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, this corresponds to an increase from 255 Indigenous Australians working in health-related occupations per 10,000 population, to 309 per 10,000 population (Table D3.12.12, Figure 3.12.4). Over half (54%) of this increase was due to increased numbers of nurses and midwives, which increased from 63 to 94 per 10,000 population between 2011 and 2021 (Table D3.12.12). The rate of medical practitioners in the Indigenous population aged 15 and over increased from 3.7 per 10,000 population in 2011 to 7.8 per 10,000 population in 2021.

Among non-Indigenous Australians, rates of employment in health-related occupations also increased between 2011 and 2021 (from 422 to 516 per 10,000 population) (Table D3.12.12, Figure 3.12.4). The increase was larger than for Indigenous Australians, which resulted in an increase in the gap (absolute difference) in rates for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. The rate difference for employment in health-related occupations increased from 167 to 206 per 10,000 population between 2011 and 2021. However, the relative difference in rates (as measured by the rate ratio) remained steady, with the rate for Indigenous Australians around 60% of the rate for non-Indigenous Australians in all 3 Censuses (rate ratio 0.6).

Across states and territories, the rate of Indigenous Australians employed in health-related occupations increased between 2011 and 2016 for all jurisdictions except Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Between 2016 and 2021, there were increases in the rate of employment in health-related occupations among Indigenous Australians in all jurisdictions (Table D3.12.13).

For non-Indigenous Australians, the rate of employment in health-related occupations increased in all states and territories between 2011 and 2016, and between 2016 and 2021 (Table D3.12.13). The gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was wider in 2021 than in 2011 across all jurisdictions.

Figure 3.12.4: Rate of people aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations, by Indigenous status, Australia, 2011 to 2021

Note: Rate per 10,000 is the number of employed Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over in the specified occupation divided by the total number of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over as counted in the Census, excluding those who did not state their occupation, and multiplied by 10,000. See Table D3.12.12 for additional data.

Source: Table D3.12.12, AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2011, 2016 and 2021 (ABS 2011, 2016, 2022).

Based on data for registered health professionals, between 2013 and 2021:

- the number of Indigenous Australians employed as medical practitioners increased from 234 to 563, and the proportion of total medical practitioners who were Indigenous increased from 0.8% to 1.4% (Table D3.12.10)

- the number of Indigenous Australians employed as nurses and midwives increased from 2,434 to 5,135, and the proportion of all nurses and midwives who were Indigenous increased from 0.3% to 0.5% (Table D3.12.7).

Research and evaluation findings

Indigenous Australians’ use of health services increases when they can receive culturally appropriate care (Roseby et al. 2019). In a Queensland clinic, Indigenous patient attendance increased markedly following the arrival of an Indigenous doctor and in response to other changes in the service designed to make it more welcoming. An Indigenous doctor was said to be ‘more understanding of their needs’ (Hayman N. 1999; Lawrence et al. 2009). Indigenous patients have identified the absence of Indigenous workers and adverse treatment by non-Indigenous health workers as barriers to the accessibility, quality and effectiveness of health care (Aspin et al. 2012).

Focus group and telephone interviews conducted in 1995 to evaluate poor attendance by Indigenous Australians at a mainstream general practice in Inala (south-western Brisbane) found that barriers included a lack of Indigenous staff, few items that Indigenous people could identify with (for example, artwork, staff perceived as unfriendly, inflexibility regarding time, and intolerance of Indigenous children’s behaviour (Hayman N.E. et al. 2009). Five key strategies were developed and implemented to address these issues, one of which was more Indigenous staff. The other strategies included a culturally appropriate waiting room, cultural awareness, informing the Indigenous community, and promoting intersectoral collaboration. Use of the health service by Indigenous Australians improved after the issues were addressed, and attendance increased significantly over the period from 1995 to 2008.

Aboriginal Medical Services (AMS) provide a culturally appropriate alternative to mainstream health services that can improve service uptake. Participants in a Brisbane study of government-controlled AMS and ACCHS reported marked health improvements in their communities due to the establishment of these services, and their important role in addressing the negative effects of discrimination on health (Baba et al. 2014). AMS provide holistic care that corresponds with the complex concepts of health shared by Indigenous Australians (Baba et al. 2014). ACCHSs are also the primary setting for employment and training of Indigenous Australians in Aboriginal Health Worker positions and offer pathways for tertiary education and professional training (Campbell et al. 2018).

In a study of census data over 2006–2016, Wright and others (2018) examined self-reported employment data to estimate the number of Indigenous health workers, using the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations category of ‘Indigenous health worker’ (Wright et al. 2019). They found growth in the number of Indigenous health workers to be incommensurate with population growth. This analysis also concluded that the Indigenous health workforce was ageing, and that there had been a reduction in the share of health workers who were male. The authors recommended that more effort is needed to improve recruitment and retention, particularly of younger age groups and males.

A review of strategies to strengthen the workforce in the Indigenous primary health-care sector found that the engagement and retention of Indigenous health professionals have been supported in a number of ways, including: co-worker support and peer mentoring; inclusiveness, workplace cultural safety and culturally competent human resources policy and practice; role recognition and clear definition of roles; job security and adequate remuneration; and support for expanded roles and career progression (Jongen et al. 2019).

The New South Wales Aboriginal Population Health Training Initiative (APHTI) was established in 2011 by the New South Wales Government to strengthen the Indigenous workforce with suitably trained and skilled public health practitioners (Li et al. 2017). The APHTI is a three-year public health training program for Indigenous Australians, in which trainees undertake a series of supervised work placements in population health and complete a Master of Public Health degree. A 2014 evaluation, and subsequent program outcomes, have shown the APHTI to be successful, with high retention and completion rates—noting that the program to date had involved a relatively small number of 18 participants. The APHTI’s success was attributed to: enabling trainees to stay within their communities; simultaneous work and study enabling trainees to develop skills and achieve competencies; and strong leadership and support from the New South Wales Government.

The Home Medicines Review (HMR) program aims to improve medication management and adherence. In 2009, the Danila Dilba Health Service in Darwin adjusted its HMR program to include an expanded role for a dedicated consultant pharmacist and an Aboriginal Health Worker to help identify patients for HMR referral, as well as coordination of the HMR process (Deidun et al. 2019). Involving Aboriginal Health Workers in the HMR process has been identified as an essential requirement for the success of Indigenous HMR programs. The in-depth community knowledge of Aboriginal Health Workers, strong relationships between Aboriginal Health Workers and pharmacists, and the provision of culturally appropriate medicines campaigns are key to effective use of medicines in Indigenous communities. A 2010 evaluation of the Danila Dilba Health Service HMR program found that general practitioners and pharmacists acknowledged the importance of Aboriginal Health Worker involvement in HMR activities and of them consistently accompanying the pharmacist. Access to, and the effectiveness of, HMRs were improved by including Aboriginal Health Worker assistance and having a culturally competent pharmacist conduct the HMR.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) established the Faculty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health in 2010 to ensure GPs were well resourced and supported to provide culturally responsive patient-centred care for Indigenous Australians. In addition, the RACGP also developed Yagila Wadamba, a support program for Indigenous general practice registrars that provides individualised support to candidates to achieve success in their fellowship exams and other key aspects of their GP training. By the end of the 2018–19 financial year the RACGP had 55 Indigenous doctors in training and 65 Indigenous fellows (RACGP 2019).

The Australian Indigenous Doctors’ Association (AIDA) conducted a 2016 survey of members on bullying, racism and lateral violence in the workplace, with the results confirming the reality and prevalence of unsafe work environments, particularly for AIDA’s Indigenous members (AIDA 2017). The survey results inform AIDA’s mentoring program and ongoing collaboration with medical colleges, universities and government to improve cultural safety.

Growing the Indigenous medical workforce is a long-term process, and requires change at all stages of the medical education and training continuum (Gannon 2017). Programs at three medical schools in New South Wales, Western Australia and Queensland are based around alternative entry schemes that assess a student’s ability using a more comprehensive range of criteria than an academic score (Lawson et al. 2007). The programs entail various combinations of recruitment strategies, premedical preparation, academic, social and personal support during the course, and flexible pathways. A 2019 systematic review found that the most successful strategies by nursing, health and medical science faculties to improve Indigenous student retention included: comprehensive orientation and pre-entry programs; building a supportive and enabling school culture; embedding Indigenous content throughout the curriculum; developing mentoring and tutoring programs; flexible delivery of content; providing social and financial support; and ‘leaving the door open’ for students to return (see measure 3.20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples training for health related disciplines) (Taylor et al. 2019).

The Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) develops and supports recruitment strategies aimed at Indigenous Australian nurses and midwives (CATSINaM 2019). CATSINaM has developed and distributed workplace resources to help improve the workforce experience of Indigenous nurse and midwife members, and runs the CATSINaM Mentoring Program which aims to reform the organisational culture of mainstream health services and improve communication in workplace and clinical contexts. Evaluations of the mentoring workshops suggest the mentoring program is helping to improve the workplace experience of Indigenous nurses and midwives. CATSINaM are also funded to provide the Leaders in Indigenous Nursing and Midwifery Education Network (LINMEN). The purpose of LINMEN is to support nursing and midwifery educators to provide the highest quality education and training on cultural safety, Indigenous health, history and culture, and support the recruitment and retention of Indigenous nurses and midwives.

The under-representation of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce places pressure on Indigenous health professionals. A systematic review of the available literature found that barriers to the retention of Indigenous health professionals include heavy workloads, poorly defined roles and responsibilities and wage disparity (Lai et al. 2018). Work environment was an enabler in workplaces with respect for Indigenous culture, but racism was reported as a major barrier in other work environments. The influence of community could be a strong personal motivator, or a source of stress due to work/life boundaries becoming blurred. A review of evidence by Topp and others (2018), on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers’ governance arrangements and accountability relationships, found that the profession faces serious challenges in its implementation and governance (Topp et al. 2018). These include a lack of state or national scopes of practice resulting in pressure being placed on individual Indigenous health workers to meet ambitious expectations, and balancing community obligations with those of their clinical service managers. Such issues appear to be contributing to difficulties in recruitment as well as retention.

The Career Pathways Project found focusing on five factors can greatly contribute to increasing health workforce participation for Indigenous Australians and reducing health disparities. These are: involving Indigenous Australians in leadership roles to lead community-specific health strategies; promoting cultural safety in health organisations to combat racism and other barriers faced by Indigenous health staff; adopting a community-led service model that respects and incorporates Indigenous culture, improving the connection with and health of the communities; investing in a diverse range of services and job opportunities, facilitating early career entry, mentorship, and advancement; and offering flexible further training and study opportunities, recognising the unique challenges faced by Indigenous health workers, and ensuring their contribution is appropriately acknowledged and remunerated (Bailey J et al. 2020).

Implications

Increasing the number of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce is fundamental to improving health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. While numbers have increased in the past decade, Indigenous Australians remain under-represented in the health workforce and growth in the number of Indigenous health workers is not keeping up with population growth. In addition to recruiting more Indigenous Australians into the health workforce, supporting existing Indigenous health workers to remain in the workforce is essential. However, there is a lack of evidence on workplace strategies to improve retention, and of evaluations of such strategies, with more written about barriers than enablers (Lai et al. 2018). Timely data and research are needed to better understand retention and turnover rates, and the factors affecting pathways into health careers and retention of Indigenous clinicians in particular health fields (Lai et al. 2018). Improving opportunities for advancement also requires attention. Access to employment in a broad range of settings and occupations is needed to avoid under-representation in better remunerated, more skilled and managerial positions for Indigenous health professionals.

A number of initiatives are underway to address these challenges. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan 2021-2031 (National Workforce Plan) sets the overarching strategic directions to grow and develop the Indigenous health workforce and identifies implementation strategies to support their intended outcomes.

The National Workforce Plan was developed in partnership with the First Nations community controlled health sector and governments and sets an ambitious target for Indigenous people to achieve proportional representation (3.43%) within the national health workforce by 2031. In support of this overarching objective, the National Workforce Plan consists of six strategic directions:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are represented and supported across all health disciplines, roles and functions.

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce has the necessary skills, capacity and leadership across all health disciplines, roles and functions.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are employed in culturally safe and responsive workplace environments that are free of racism across health and all related sectors.

- There are sufficient numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students studying and completing health qualifications to meet the future health care needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health students have successful transitions into the workforce and access clear career pathway options.

- Information and data are provided and shared across systems to assist health workforce planning, policy development, monitoring and evaluation, and continuous quality improvement.

Under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, parties to the Agreement committed to building strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled sectors that include dedicated and identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforces. Supporting this commitment, a three-year Health Sector Strengthening Plan was agreed in December 2021 by the Closing the Gap Joint Council outlining actions that will support and build the Aboriginal community controlled health sector, including four actions targeted to workforce.

The Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives (CATSINaM) published the ‘Gettin em n keepin em n growin em’ (GENKE II) Plan. GENKE II contains commitments to developing frameworks for collaboration and partnerships between CATSINaM and a wide range of government and peak stakeholders in order to develop the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing and midwifery workforce. Training in cultural awareness is important for non-Indigenous health-care providers. The cultural awareness training programs that are currently offered, however, could be improved (Aspin et al. 2012). Indigenous cultural awareness training tends to homogenise Indigenous cultures, and position them as distinct from the ‘norm’. An increased emphasis on reflexivity and self-awareness in training could help health workers to better understand their own values and beliefs, and how they shape the care that they provide. It is acknowledged that cultural education needs to be ongoing, and localised to the region in which health care providers are working (Kerrigan et al. 2020). There is, however, a need for more research and evaluation of training programs to understand what works (Downing et al. 2011).

The Australian Government is investing in scholarships and programs to bolster Indigenous Australians' participation in the health workforce. This includes funding for programs designed to help Indigenous Australians commence, continue, and complete their health-related studies, and to further their professional development. The Australian Government funds Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Professional Organisations (ATSIHPOs) to support and develop the growing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce. Funding also supports work to increase the cultural capability of the broader health workforce, to support better care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Included in this work is the Indigenous Allied Health Australia’s (IAHA) Health Academy Program. This program works with high school students from Years 7-12, starting with health literacy, moving to leadership and career planning and transitioning into the Health Academy in Years 11 and 12. IAHA’s Health Academy supports participants to enter a school-based traineeship pathway, complete a Year 12 qualification, gain work experience and obtain a Certificate III in Allied Health Assistance.

The Australian Government is working in partnership with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to deliver the First Nations Health Worker Traineeship Program, which will support up to 500 First Nations trainees to undertake Certificate III or IV accredited training to enable them to work across various health settings and be able to deliver culturally appropriate care to First Nations peoples. First Nations trainees will come out of the program with the right skills and support to transition successfully into jobs in the health sector – they will receive on-the-job experience and mentoring in local ACCHSs. Training, which will be provided by Aboriginal Community Controlled Registered Training Organisations (ACCRTOs), will be delivered as close to home – On Country – as possible.

The Australian Government supports the Puggy Hunter Memorial Scholarship Scheme, which pays tribute to Doctor Arnold ('Puggy') Hunter's contributions to Indigenous health by offering financial assistance to Indigenous undergraduate students in health disciplines. The scheme is managed by the Australian College of Nursing. The Australian Government also funds the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Pharmacy Scholarship Scheme for pharmacy students. The Australian Rotary Health: Indigenous Health Scholarships, which cover everyday expenses and offers mentorship for students in health-related fields, receives funding from multiple sources including Australian Rotary Health, Rotary clubs, some state and territory governments, and the Australian Government (DoHAC 2021).

Improving the representation of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce will require collaboration between the health and education sectors. Addressing educational disadvantages faced by Indigenous children can help them to develop skills and be ready to pursue a career in the health sector (see measures 2.04 Literacy and numeracy and 2.05 Education outcomes for young people). Strategies to address barriers, highlight pathways into health careers, and strengthen support for Indigenous students and improve their rate of retention need to be implemented (see measure 3.20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples training for health-related disciplines).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2011. 2011 Census - counting persons, place of usual residence [Census TableBuilder Pro product].

ABS 2016. 2016 Census - counting persons, place of usual residence [Census TableBuilder Pro product].

ABS 2022. 2021 Census - counting persons, place of usual residence [Census TableBuilder Pro product].

AH&MRC (Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council) 2015. Aboriginal communities improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review on the contribution of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health. Sydney.

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2016. Cultural Respect Framework 2016-2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Canberra: AHMAC.

AHPRA (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency) 2022. 2021/22 Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency Annual Report. Melbourne: AHPRA.

AIDA (Australian Indigenous Doctors' Association) 2017. Report on the findings of the 2016 AIDA member survey on bullying, racism and lateral violence in the workplace. Canberra.

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2023. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander specific primary health care: results from the nKPI and OSR collections. Canberra: AIHW.

Anderson I, Ewen SC & Knoche DA 2009. Indigenous medical workforce development: current status and future directions. The Medical Journal of Australia 190:580-1.

Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, Yen L & Leeder S 2012. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC health services research 12:143.

Baba JT, Brolan CE & Hill PS 2014. Aboriginal medical services cure more than illness: a qualitative study of how Indigenous services address the health impacts of discrimination in Brisbane communities. International Journal for Equity in Health 13:1-10.

Bailey J, Blignault llse, Carriage C, Demasi K, Joseph T-L, Kelleher K et al. 2020. We Are working for our People: Growing and Strengthening the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce: Career Pathways Project Report. Carlton, Vic.

Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

CATSINaM (Congress of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Nurses and Midwives) 2019. Annual Report 2018-19. Canberra.

de Witt A, Cunningham FC, Bailie R, Percival N, Adams J & Valery PC 2018. “It's Just Presence,” the Contributions of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Professionals in Cancer Care in Queensland. Frontiers in public health 6:344.

Deidun D, Ali M, Madden A & O'Brien M 2019. Evaluation of a home medicines review program at an Aboriginal Medical Service in the Northern Territory. Journal of Pharmacy Practice and Research 49:486-92.

DoHAC (Department of Health and Aged Care) 2021. Jobs and scholarships supporting the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce. (ed., Care DoHaA). Canberra.

Downing R, Kowal E & Paradies Y 2011. Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 23:247-57.

Freeman T, Edwards T, Baum F, Lawless A, Jolley G, Javanparast S et al. 2014. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: beyond education and training of practitioners. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 38:355-61.

Gannon M 2017. Indigenous taskforce: Indigenous medical workforce. Australian Medicine 29:22.

Hayman N 1999. The poor health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples: Can more Indigenous doctors make a difference? New Doctor:19-21.

Hayman NE, White NE & Spurling GK 2009. Improving Indigenous patients’ access to mainstream health services: the Inala experience. The Medical Journal of Australia 190:604-6.

Jongen C, McCalman J, Campbell S & Fagan R 2019. Working well: strategies to strengthen the workforce of the Indigenous primary healthcare sector. BMC health services research 19:910.

Kerrigan V, Lewis N, Cass A, Hefler M & Ralph AP 2020. “How can I do more?” Cultural awareness training for hospital-based healthcare providers working with high Aboriginal caseload. BMC Medical Education 20:1-11.

Lai G, Taylor E, Haigh M & Thompson S 2018. Factors affecting the retention of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce: a systematic review. International journal of environmental research and public health 15:914.

LaVeist TA, Nuru-Jeter A & Jones KE 2003. The Association of Doctor-Patient Race Concordance with Health Services Utilization. Journal of Public Health Policy 24:312-23.

Lawrence M, Dodd Z, Mohor S, Dunn S, De Crespigny C, Power C et al. 2009. Improving the patient journey: Achieving positive outcomes for remote Aboriginal cardiac patients.

Lawson KA, Armstrong RM & Van Der Weyden MB 2007. Training Indigenous doctors for Australia: shooting for goal. Medical Journal of Australia 186:547-50.

Li B, Cashmore A, Arneman D, Bryan-Clothier W, McCallum L & Milat A 2017. The Aboriginal Population Health Training Initiative: a NSW Health program established to strengthen the Aboriginal public health workforce. Public Health Research & Practice.

Powe NR & Cooper LA 2004. Diversifying the racial and ethnic composition of the physician workforce. Annals of Internal Medicine 141:223-4.

RACGP (Royal Australian College of General Practitioners) 2019. Annual report 2018-19. East Melbourne, Victoria.

Roseby R, Adams K, Leech M, Taylor K & Campbell D 2019. Not just a policy; this is for real. An affirmative action policy to encourage Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples to seek employment in the health workforce. Internal Medicine Journal 49:908-10.

Scrimgeour M & Scrimgeour D 2008. Health care access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in urban areas, and related research issues: a review of the literature. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health.

Taylor EV, Lalovic A & Thompson SC 2019. Beyond enrolments: a systematic review exploring the factors affecting the retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health students in the tertiary education system. International Journal for Equity in Health 18:136.

Topp S, Edelman A & Taylor S 2018. ‘We are everything to everyone’: a systematic review of factors influencing the accountability relationships of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers (AHWs) in the Australian health system. International Journal for Equity in Health 17.

West R, Usher K & Foster K 2010. Increased numbers of Australian Indigenous nurses would make a significant contribution to 'closing the gap' in Indigenous health: What is getting in the way? Contemporary Nurse 36:121-30.

Wright A, Briscoe K & Lovett R 2019. A national profile of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers, 2006–2016. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 43:24-6.