Key messages

- Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) is a disease of disadvantage that is both preventable and treatable. RHD is caused by damage to the valves of the heart as a result of one or repeated episodes of acute rheumatic fever (ARF).

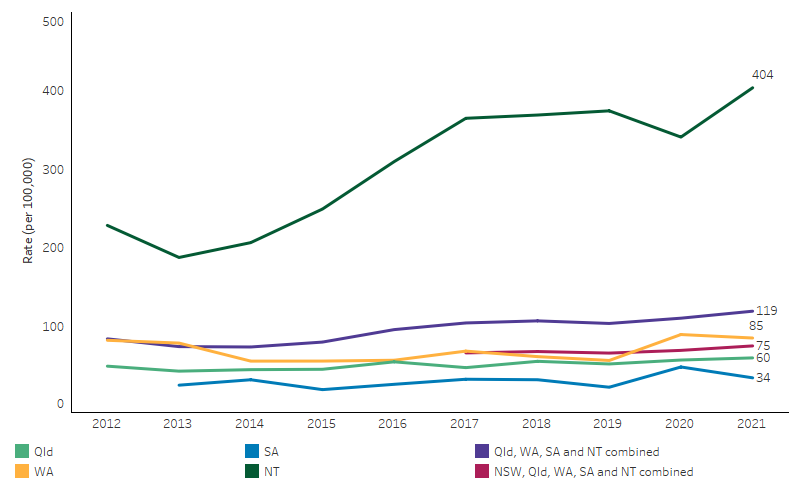

- In the decade from 2012 to 2021, incidence rates of ARF among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people increased from 84 per 100,000 to 119 per 100,000 for Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory (combined). This was driven by an increase in the Northern Territory, where the rate of ARF among First Nations people increased by 108% over the period.

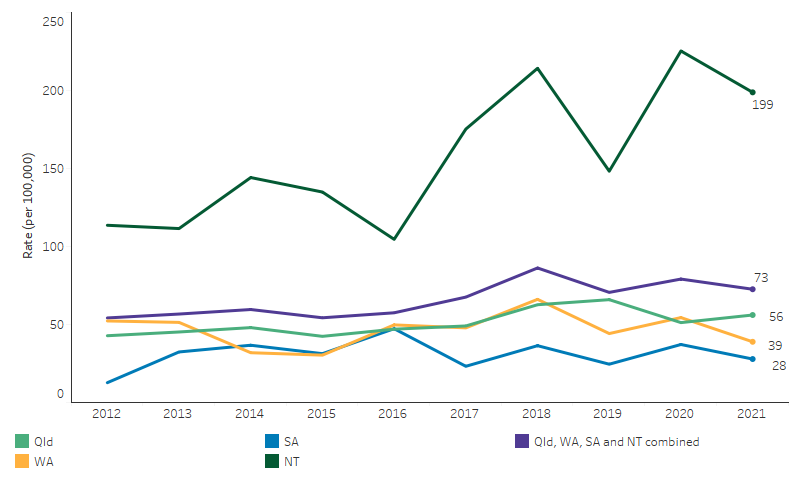

- From 2012 to 2021, the incidence rate of RHD among First Nations people in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory (combined) increased by 50%. This reflects increases in RHD incidence in the Northern Territory which almost doubled (98% increase), and in Queensland (40% increase) with no significant change in South Australia or Western Australia.

- Among First Nations people 28% of ARF cases were recurrent – that is, the cases occurred among people who had previously experienced ARF or RHD episodes. The remaining 71% of cases were first known episodes.

- The prevalence of RHD was higher for First Nations females than males. In the 3 jurisdictions for which data were available by sex, the rate of RHD was around twice as high for First Nations females as for males.

- First Nations people accounted for 92% of the total number of ARF cases recorded over the 5-year period 2017–2021 in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory combined.

- First Nations people were hospitalised for ARF or RHD at 6.4 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (82 and 13 per 100,000, respectively) between July 2017 and June 2019.

- Recommended ARF and RHD preventative measures include monitoring Group A Streptococcus (GAS) diseases, the development of a GAS vaccine, long-acting penicillins, and improvements in social and environmental factors, along with improved housing and better access to health care.

- The RHD Endgame Strategy aims to end RHD in Australia by 2031. It identifies the critical role of housing and environmental health policies in addressing the disease, especially in remote First Nations communities.

- To improve care for people and communities living with RHD, concerted efforts are required to shift the focus of health care so that the services are flexible, culturally safe, adaptive to local context and are family/community-based. Providing good quality care requires health service providers to overcome cultural inappropriateness and institutional racism.

- Findings of this measure need to be interpreted in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had negative impacts on First Nations people’s health and wellbeing as reflected in the data presented in this measure.

Why is it important?

ARF and RHD are preventable diseases disproportionately affecting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people living in regional and remote areas of Australia (AIHW 2023). First Nations people in Australia have one of the highest recorded rates of ARF and RHD in the world and large disparities exist between First Nations people and other Australians (AIHW 2013; Menzies School of Health Research 2023).

ARF is an inflammatory illness caused by an autoimmune reaction to a throat or skin Group A Streptococcus (GAS) bacterial infection, such as that following impetigo and scabies. These skin infections are likely to have a direct or indirect role in the development of ARF and RHD (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2020). Scabies is a skin condition caused by an infestation of microscopic mites which results in an itchy rash, and the scratching of affected areas may result in a GAS bacterial infection of the skin (impetigo) (Romani et al. 2017). Scabies is common in many remote communities (Northern Territory Government 2020). GAS infection risk is associated with socioeconomic factors such as household crowding (Coffey et al. 2018).

ARF symptoms can include arthritis, fever, swelling of the heart and heart valves, and rash (Ralph 2020). Following diagnosis of ARF, patients require long-term treatment and follow-up, including long-term intramuscular antibiotic prophylaxis to avoid further infections that could damage the heart (AIHW 2013; RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2020). RHD is permanent damage to the valves of the heart caused by one or repeated episodes of ARF. One episode of ARF increases the risk of repeated episodes, which can increase the risk of RHD. Heart surgery can be required to repair heart valve damage resulting from RHD. Primary health-care providers can play an important role in identifying ARF and supporting adherence to treatment within the context of a complex interplay of cultural and socioeconomic factors (Coffey et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2012).

ARF and RHD are associated with social and environmental factors such as poverty, overcrowded housing and poor functioning of ‘health hardware’ such as facilities for washing people, clothes and bedding (Ali et al. 2018). They are now rare diseases in populations with good living conditions and timely access to effective medical care (He et al. 2016; Health Policy Analysis 2017). However, ARF and RHD are far more likely to occur among First Nations people living in remote communities where there are higher rates of overcrowded or poorly functioning housing. Socioeconomic disadvantage and barriers to accessing health care need to be addressed to reduce the occurrence of ARF and RHD. To improve care for people and communities living with RHD, concerted efforts are required to shift the focus of health care so that services are flexible, culturally safe, adaptive to local context and are family/community-based. Providing good quality care requires health service providers to overcome cultural inappropriateness and institutional racism (Haynes et al. 2020).

In 2009, the Australian Government’s Rheumatic Fever Strategy (RFS) was established to improve detection, monitoring and management of ARF and RHD through register-based control programs in the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland, with the subsequent addition of South Australia.

This measure presents information from the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection, collated from the ARF and RHD registers in these 4 jurisdictions. An RHD control program and register operates in New South Wales but is not covered under the RFS and is not part of the National RHD data collection. Data from New South Wales are presented in this measure when definitions and reporting protocols are comparable to other jurisdictions, and in standalone data or figures where they are not comparable.

Rates of ARF and RHD among First Nations people and communities need to be interpreted and understood in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and cultures. This history and the ongoing impacts of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and poorer outcomes for First Nations people.

In July 2020, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people and communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and live in appropriate, affordable housing that is aligned with their priorities and needs. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031,

- Target 9a: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing to 88 per cent.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan) provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations health and wellbeing, and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement. The Health Plan highlights that efforts to combat ARF and RHD through early intervention and improving environmental health conditions remain key priorities.

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Burden of disease

For First Nations people in 2018, RHD and ARF was the fourth leading cause contributing to the cardiovascular disease total burden, accounting for 5% (1,208 disability-adjusted life years, or DALY) of the total burden for this disease group.

In 2018, 86% of the burden due to RHD and ARF was fatal (with 1,036 years of life lost due to dying prematurely), with the remaining 14% due to years lived with illness (172 years of healthy life lost).

Among First Nations people aged 5–14 and 15–24 years, RHD and ARF were the leading causes of cardiovascular disease total burden (46% and 25%, respectively). Of the 1,208 DALY due to RHD and ARF experienced by First Nations people, 61% of the burden was experienced by First Nations females (738 DALY) and 39% was experienced by First Nations males (470 DALY). The age-standardised rate of burden due to RHD and ARF for First Nations people was 11 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians. This represented the largest relative difference between the two populations for cardiovascular diseases (AIHW 2022a, 2022b).

Data findings

Acute rheumatic fever cases

For the period reported, 2017 to 2021 combined, comparable data on ARF cases are available for 5 jurisdictions: New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

Over the 5-year period from 2017 to 2021 in these jurisdictions combined, 2,570 cases of ARF were diagnosed among First Nations people (Table D1.06.1). First Nations people accounted for 92% of the total number of ARF cases recorded (2,781, excluding cases where Indigenous status was unknown). First Nations people experienced ARF at a rate of 68.9 cases per 100,000 population, compared with 0.3 cases per 100,000 population for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.06.1).

Of 2,570 ARF cases among First Nations people in 2017–2021, 71% of ARF cases (1,814) were first known episodes, representing people diagnosed with ARF for the first time. The remaining 28% of ARF cases (728) were recurrent – that is, the cases occurred among people who had experienced ARF previously or had existing RHD (Table D1.06.5).

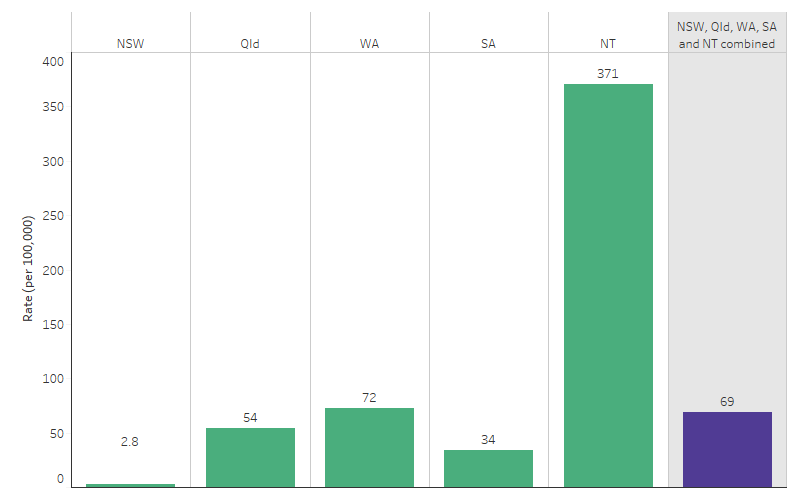

Across the 5 jurisdictions:

- The total number of ARF cases (first known and recurrent combined) was highest in the Northern Territory (1,426 cases), followed by Queensland (644), Western Australia (385), South Australia (76) and New South Wales (39).

- The population rate of ARF cases was highest in the Northern Territory (371 cases per 100,000 population), followed by Western Australia (72 per 100,000 population).

- The proportion of ARF cases that were recurrent ranged from 18% in New South Wales to 31% in the Northern Territory (Tables D1.06.1, D1.06.5, Figure 1.06.1).

Figure 1.06.1: Acute rheumatic fever incidence in First Nations people, by jurisdiction, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory, 2017–2021

Source: Table D1.06.1. AIHW analysis of the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection.

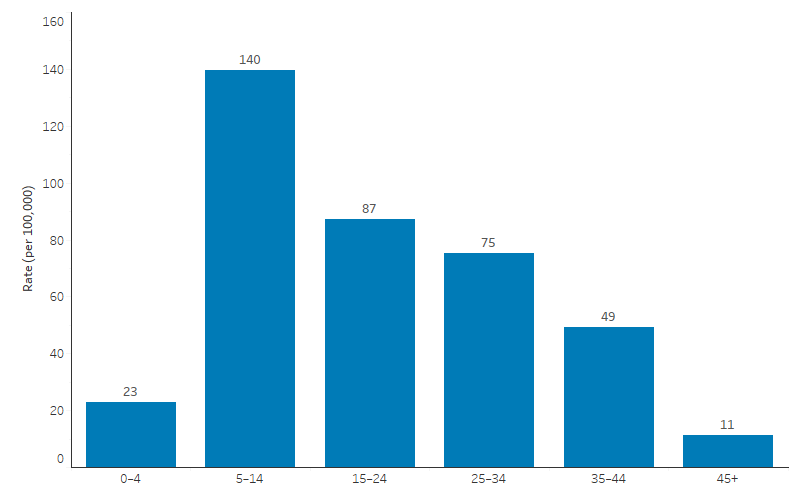

In 2017–2021, 44% of ARF cases among First Nations people occurred in children aged 5–14 (1,142 cases or 140 per 100,000). This was followed by those aged 15–24 (624 cases or 87 per 100,000) and those aged 25–34 (420 cases or 75 per 100,000). ARF incidence rates for First Nations people aged 45 and over were the lowest compared with other age groups (92 cases or 11 per 100,000) (Table D1.06.5, Figure 1.06.2).

Figure 1.06.2: Distribution of acute rheumatic fever diagnoses among First Nations people, by age, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined, 2017–2021

Source: Table D1.06.5. AIHW analysis of the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection.

Rheumatic heart disease cases

Data on RHD cases are available for Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. Data are also available from New South Wales, however RHD is only notifiable for those aged under 35 in New South Wales, and so data are not comparable with those from the other 4 jurisdictions (see also Box 1.06.1).

As at 30 December 2021:

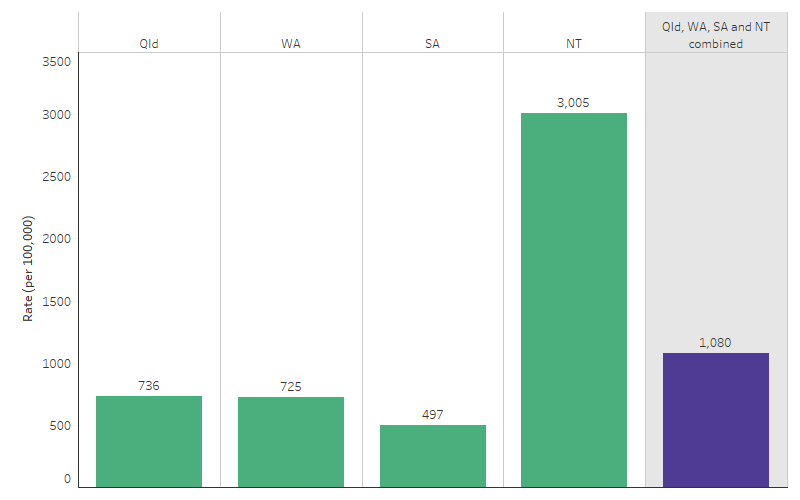

- There were 5,221 First Nations people with RHD, equivalent to 1,080 cases per 100,000 population.

- 11% of First Nations people with RHD were aged under 15 (550 people), 44% were aged between 15 and 34 (2,305), and 45% were aged 35 and over (2,366) (Table D1.06.11).

The prevalence rate of RHD among First Nations people in the Northern Territory was 3,005 per 100,000 people (or 2,358 people diagnosed with RHD), compared with 736 per 100,000 in Queensland (1,823), 725 per 100,000 in Western Australia (801), and 497 in South Australia (232) (Figure 1.06.3).

Figure 1.06.3: Rheumatic heart disease prevalence in First Nations people, by jurisdiction, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory, as at 31 December 2021

Source: Table D1.06.7, D1.06.8, D1.06.9, D1.06.10 and D1.06.11. AIHW analysis of the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection.

Data on RHD prevalence is also available for New South Wales, though only for those aged under 35 at diagnosis. As at 31 December 2021, 40 First Nations people aged under 35 had been diagnosed with RHD in New South Wales – a rate of 20 cases per 100,000 population (Table D1.06.23).

The prevalence of RHD was higher for First Nations females than males. In the 3 jurisdictions for which data were available by sex, the rate of RHD was around twice as high for First Nations females as for males:

- In the Northern Territory, the prevalence of RHD for First Nations females was 3,998 per 100,000 population (1,541 cases), compared with 2,047 per 100,000 for First Nations males (817 cases).

- In Queensland, the prevalence of RHD for First Nations females was 945 per 100,000 population (1,179 cases), compared with 523 per 100,000 for First Nations males (644 cases).

- In South Australia, the prevalence of RHD for First Nations females was 658 per 100,000 population (155 cases), compared with 333 per 100,000 for First Nations males (77 cases) (Table D1.06.7, Table D1.06.9, Table D1.06.10).

In the 5-year period 2017–2021, there were 1,750 new RHD cases among First Nations people (AIHW 2023). Of these new cases, 49% (740 cases) had mild RHD when first diagnosed, 32% (473 cases) had moderate RHD and 19% (285 cases) had severe RHD. The distribution of new RHD severity at diagnosis for First Nations people was broadly similar across the 4 jurisdictions, with between 46% and 54% of cases in each jurisdiction classified as mild, between 26% and 34% as moderate, and between 16% and 24% as severe.

First Nations people are substantially over-represented among people with RHD. As at 31 December 2021, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory combined:

- Nearly 8 in 10 people with RHD (78%) were First Nations people (excluding cases where Indigenous status was unknown), compared with First Nations people making up around 5% of the total population of these jurisdictions in 2021 (ABS 2021a, 2021b).

- As a population rate, there were 1,080 RHD cases per 100,000 First Nations people, compared with 15 per 100,000 for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.06.11).

In New South Wales:

- About one-third (34%) of people with RHD cases were First Nations people (excluding cases where Indigenous status was unknown), compared with First Nations people making up around 4% of the New South Wales population in 2021 (ABS 2021a, 2021b).

- As a population rate, there were 20.3 RHD cases per 100,000 population among First Nations people aged under 35, compared with 2.3 per 100,000 for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.06.23).

Antibiotic treatment for ARF and RHD

Secondary prophylaxis refers to the antibiotics, benzathine benzylpenicillin, also known as benzathine penicillin G (BPG), given to people who have been diagnosed with ARF and/or RHD to prevent further GAS infections, thereby reducing the risks of developing ARF again and of developing or worsening RHD.

Data are presented for Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. New South Wales has different criteria and data are not comparable to the other jurisdictions. Proportion of doses delivered is calculated as a proportion of the scheduled 13 doses per year for patients on a 28-day BPG regime, and 17 doses for patients on a 21-day regime. Patients who commenced partway through the year have been included with an adjusted expected number of doses. Patients who should have been on BPG but did not receive a dose in 2021 were also included in the analysis.

In Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined, there were 4,816 First Nations people eligible for inclusion in calculations about BPG delivery in 2021. Of these:

- 18% (875 people) received 100% or more of their prescribed doses

- 13% (638) received 80% to 99% of their prescribed doses

- 27% (1,319) received 50% to 79% of their prescribed doses

- 41% (1,984) received less than 50% of their prescribed doses, including 514 people who did not receive any doses (AIHW 2023).

Receiving at least 80% of the scheduled doses is widely used as an indicator of adherence which is likely to protect against ARF recurrences (AIHW 2020). In the 4 jurisdictions combined, 31% (1,513) of First Nations people received at least 80% of prescribed doses in 2021. Across the 4 jurisdictions, the proportion of First Nations people prescribed secondary prophylaxis who received at least 80% of the required doses was:

- 52% in South Australia

- 41% in the Northern Territory

- 20% in Queensland

- 18% in Western Australia (Table D1.06.16).

In New South Wales, details of patients prescribed or administered prophylaxis are recorded on the register only if they have consented to be included. In 2021, 40% of people with ARF and/or RHD in New South Wales consented to being on the prophylaxis register. Of 32 people for whom data was available, 28% received at least 80% of the required doses (Table D1.06.16).

Hospital treatment due to ARF and RHD

Australian guidelines recommend that anyone suspected to have ARF should be admitted to a hospital within 24–72 hours for echocardiography and specialist review (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022). As such, hospitalisations may not reflect severity.

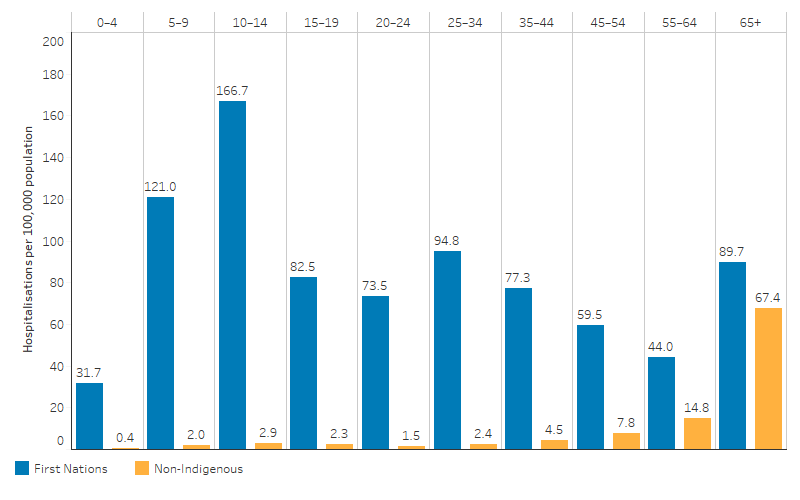

Between July 2017 and June 2019, 1,428 First Nations people were hospitalised for ARF or RHD (86 per 100,000 population). It contributed to 0.13% of all hospitalisations for First Nations people (Table D1.06.20, Table D1.02.5). First Nations females were hospitalised for ARF or RHD at higher rates than First Nations males (103 and 69 per 100,000, respectively) (Table D1.06.20).

Hospitalisation rates for ARF or RHD varied by jurisdiction, with the highest rate in the Northern Territory (481 per 100,000), followed by Western Australia (108 per 100,000) (excludes Victoria, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory as the data was not published due to privacy or reliability reasons) (Table D1.06.17).

Hospitalisation rates for ARF or RHD for First Nations people were higher among First Nations people living in remote areas (Remote and very remote areas combined) (330 per 100,000) than in non-remote areas (Major cities, inner regional and outer regional areas combined) (30 per 100,000) (Table D1.06.17).

By Indigenous status, hospitalisations for ARF or RHD were higher for First Nations people than non-Indigenous Australians across all age groups (Table D1.06.20, Figure 1.06.4). For First Nations people, the rate of hospitalisation for ARF or RHD was highest for those aged 10–14, at 167 per 100,000 (or 300 hospitalisations). For non Indigenous Australians, rates of hospitalisation for ARF or RHD were highest for those aged 65 and over (67 per 100,000 or 5,221 hospitalisations).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, First Nations people were hospitalised for ARF or RHD at 6.4 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.06.20). First Nations people were 70.4 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for ARF, while the hospitalisation rate for RHD was 3.6 times as high for First Nations people as non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.06.21 and D1.06.22).

Figure 1.06.4: Hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of acute rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease, by Indigenous status and age, Australia, July 2017 to June 2019

Source: Table D1.06.20. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Changes over time in ARF and RHD

Data on ARF over the decade from 2012 to 2021 are available for 4 jurisdictions: Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory. Data on ARF for New South Wales became available more recently and are included in this measure from 2017 onwards (the first full year of data available after the register was established during 2016).

From 2012 to 2021, incidence rates of ARF among First Nations people increased from 84 per 100,000 to 119 per 100,000 for Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined (the 4 jurisdictions with data available for the whole period) (Table D1.06.6, Figure 1.06.5). This was driven by an increase in the Northern Territory, where the rate of ARF among First Nations people approximately doubled (108% increase) over the period (based on linear regression analysis) (Table D1.06.6). However, there was no statistically significant change in Queensland or Western Australia over the same period.

Note that the increase may reflect a real increase in the number of cases occurring, but may also be due to improved detection and diagnosis of cases, increases in the number of people being recorded on the registers, or a combination of these (AIHW 2023).

Data for five jurisdictions (that is, also including New South Wales) are available for the period 2017 to 2021. Between 2017 and 2021, there was no statistically significant change the incidence rates of ARF among First Nations people in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined (Table D1.06.6).

Figure 1.06.5: Incidence of acute rheumatic fever notifications among First Nations people, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory, 2012 to 2021

Note: NSW is not shown separately in the figure due to small numbers and associated concerns around the reliability of incidence rates.

Source: Table D1.06.6. AIHW analysis of the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection.

Time trend data on RHD are available for Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined. Data for New South Wales is not comparable to data for the other jurisdictions, as RHD is only notifiable for those aged under 35 at the time of diagnosis in this state.

From 2012 to 2021, in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined, the incidence rate of RHD among First Nations people fluctuated between 54 and 86 new cases per 100,000 population. Using linear regression analysis to assess the overall trend, the incidence rate of RHD among First Nations people in these 4 jurisdictions increased by 50% (Table D1.06.15). This reflects increases in RHD incidence in the Northern Territory (98% increase), and in Queensland (40% increase) (Table D1.06.15, Figure 1.06.6), with no significant change in South Australia or Western Australia.

Note that the increase may reflect a real increase in the number of cases occurring, but may also be due to improved detection and diagnosis of cases, increases in the number of people being recorded on the registers, or a combination of these.

For New South Wales, the incidence rate of RHD among First Nations people fluctuated between 0.7 and 2.6 per 100,000 population over the period from 2017 to 2021 (AIHW 2023). There were too few cases among non-Indigenous Australians to draw meaningful conclusions about change over time.

Figure 1.06.6: Incidence of rheumatic heart disease notifications among First Nations people, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory, 2012 to 2021

Source: Table D1.06.15. AIHW analysis of the National Rheumatic Heart Disease data collection.

Research and evaluation findings

The RHD Endgame Strategy

The National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) funds the End Rheumatic Heart Disease Centre of Research Excellence (END RHD CRE). In 2020, the END RHD CRE released The RHD Endgame Strategy: the blueprint to eliminate rheumatic heart disease in Australia by 2031 (the Endgame Strategy), the result of collaboration between researchers, communities, First Nations leaders and people with lived experience of RHD (Wyber et al. 2020a).

The Endgame Strategy outlines a comprehensive approach to combatting RHD, focusing on primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention measures. Addressing RHD requires a multi-faceted approach including strengthening primary health-care services, ensuring culturally safe care, and improving data collection and research (Wyber et al. 2020a). Primary prevention focuses on preventing the initial episode of ARF, which can lead to RHD. This involves strategies like improving living conditions, increasing awareness of GAS infections, and ensuring timely treatment. Secondary prevention targets individuals who have had ARF or have RHD, to prevent recurrent episodes through secondary prophylaxis, which involves regular intramuscular injections of the antibiotic benzathine benzylpenicillin, also known as benzathine penicillin G (BPG). Tertiary care focuses on individuals already living with RHD to reduce symptoms, improve quality of life, and extend life expectancy. This involves monitoring heart function, providing advanced medical and surgical management, and ensuring access to other essential health services. To address the challenges of accessing specialist care in rural and remote areas, the Endgame Strategy identifies optimising patient travel support, implementing specialist outreach programs, leveraging telehealth consultations, and promoting initiatives like the Indigenous Cardiac Outreach Program (Wyber et al. 2020a).

Statistical modelling conducted in 2019 assessed the economic and health impacts of implementing an indicative strategy to eliminate RHD by 2031. By focusing on reducing household crowding, enhancing hygiene infrastructure, bolstering primary health care, and improving secondary prophylaxis it was estimated that this approach could prevent 663 deaths and save the health-care system $188 million (Wyber et al. 2020b).

Global burden and data linkage

Globally the majority of ARF and RHD cases are in low- and middle-income countries, where more than 80% of the world’s ARF cases occur. Global estimates indicate that the burden of RHD is highest among people living in poor-quality housing, followed by rural areas, and lowest in urban areas. Based on the estimates from the Global Burden of Disease study the highest ARF and RHD rates were found in sub-Saharan Africa, followed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, New Zealand Māori and Pacific Islanders (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022).

An epidemiological analysis of ARF and RHD in Australia from 2015 to 2017 was conducted using data linkage to gain a detailed understanding of the prevalence and incidence of ARF and RHD, with a particular focus on the First Nations population. Of the 1,425 ARF episodes identified during this period, 72.1% were first-ever episodes, and 88.8% occurred in First Nations individuals. The research underscores that First Nations people are disproportionately affected, being at least 60 times more likely to experience ARF or RHD. This pronounced disparity contributes to higher rates of stroke, atrial fibrillation, and heart failure among younger First Nations people. The study highlights that the high prevalence of ARF and RHD among First Nations people is linked to underlying social disadvantage and environmental conditions, including factors like housing, health care access, and socio-economic status. These conditions significantly heighten the susceptibility of First Nations communities to these diseases. While ARF and RHD continue to pose significant health challenges in Australia, especially for First Nations communities, leveraging data linkage approaches can offer a more precise understanding of the disease’s prevalence, thereby informing resource allocation and policy decisions (Katzenellenbogen et al. 2020).

Primordial and primary prevention

The importance of primordial and primary prevention strategies to control and prevent ARF and RHD is underlined by multiple research studies. A 2018 systematic review concluded that environmental and social factors such as household crowding and socioeconomic status had direct causal links to the risk of GAS infection, ARF and RHD (Coffey et al. 2018).

The social determinants of health, such as income, education, housing and health care, strongly influence the occurrence of ARF and RHD. Primordial prevention is the modification of social determinants of health to improve health and reduce the risk of disease acquisition and the subsequent progression to RHD. Research to develop and implement scalable primordial prevention interventions in diverse settings identified important factors including social crowding, housing conditions with access to adequate resources for washing bodies, clothing and bedding, nutrition and overall health status, and health literacy and effective health communication. There is a need for health economic assessments to demonstrate the benefit of investment in primordial, primary and secondary prevention activities. These strategies, in turn, would lower the costs and Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) associated with tertiary care for people living with RHD (Michael et al. 2023).

A suite of small studies explored aspects of a community-based intervention in several communities in remote Australia, aimed at addressing primordial and primary prevention of GAS infections, ARF and RHD. The intervention used a model addressing six domains: housing and environmental support; community awareness and empowerment; health literacy; health and education service integration; health navigation; and health provider education. The intervention aimed to train and employ community members to work with communities to share knowledge about ARF prevention, provide environmental health support such as reporting needs for repairs of health hardware in homes, and assisting families in navigating the health system. Small numbers were a limitation of the studies. However, although small, these studies provide evidence to guide larger programs and evaluations, particularly regarding the benefits of working with local communities, and the strengths and limitations that can be expected of community workers, and of health professionals working in those communities (Kerrigan et al. 2021; Ralph et al. 2022; Wyber et al. 2021).

The roll out of methods for the timely and appropriate treatment of GAS infections is a key step in eliminating ARF in Australia. Through conducting screening for GAS infections in school children in the remote Kimberley region, the importance of molecular point-of-care testing – which provides immediate and accurate results – was demonstrated (Pickering et al. 2020). The timely diagnosis of ‘Strep Throat’ allowed for rapid treatment and reduced spread of GAS infections, and reduced the chance of an ARF episode. This is in contrast to traditional, laboratory-based diagnosis methods that take several days, which delay the delivery of health care in remote settings (Telethon Kids Institute 2020). Rapid treatment of skin infections which are endemic in remote tropical Australia would also contribute to reducing the high rates of ARF and RHD (May et al. 2016).

Secondary prevention and treatment

Secondary prevention and treatment of ARF/RHD are essential for people already living with ARF and/or RHD. This care is provided through the implementation of disease registers and control programs, education of patients and their families, treatment with penicillin prophylaxis, regular clinical review and access to specialists and hospital care (Chamberlain-Salaun et al. 2016).

People diagnosed with ARF should commence secondary prophylaxis as soon as possible after diagnosis. This can be challenging for many reasons. It was found that 76% of people diagnosed with RHD in the Northern Territory between 2014 and 2018 had no previous diagnosis of ARF (Hardie et al. 2020). The authors highlighted the need for enhanced cross-sectoral efforts in risk factor prevention and primary prevention since the majority of people with RHD in the Northern Territory could have received antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent progression to RHD.

A study of long-term outcomes following RHD diagnosis in Australia focused on the progression of RHD in young Australians, spanning several jurisdictions. The study cohort consisted of 1,718 initially uncomplicated RHD cases, of which 84.6% were First Nations individuals. The findings revealed that within 8 years, 23.3% of the cohort experienced either death or a cardiovascular complication (Stacey et al. 2021).

The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of ARF and RHD recommends that anyone suspected to have ARF should be admitted to a hospital within 24–72 hours for echocardiography and specialist review (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2020). Early hospitalisation also facilitates exclusion of differential diagnosis, confirmation of the ARF diagnosis, beginning of penicillin and other ARF treatments, and education for the patient and their family about ARF/RHD. The guideline highlights that high rates of disease progression from ARF to RHD means early diagnosis is essential to inhibit disease progression through secondary prophylaxis.

A study was conducted at the Perth Children’s Hospital, the only tertiary paediatric hospital in Western Australia, from 2000 to 2018. The research aimed to describe patient characteristics and outcomes from cardiac surgery for RHD in paediatric patients. The study analysed 29 patients (59% female, 97% Aboriginal, Māori, or Pacific Islander) who underwent 41 valve interventions over 34 cardiac surgeries. The median age at the first surgery was 12.2 years. Severe mitral regurgitation was the primary reason for surgery in 62% of cases. The study found no early mortality, but one patient required early reoperation due to aortic valve repair failure. Late mortality occurred in 3 (10%) patients, all due to cardiac causes. The study concludes that outcomes for paediatric patients undergoing surgery for RHD in Western Australia are comparable to similar studies, showcasing favourable long-term survival. The research underscores the importance of surgical interventions as a treatment modality for advanced RHD, especially among First Nations people from regional and remote Western Australia (Hamsanathan et al. 2023).

Treatment adherence

Patients on prophylaxis treatment need to receive 40% of scheduled doses of penicillin to benefit from being on treatment. A 2018 study found that for every 10% increase in adherence above this 40% benchmark, the odds of an ARF recurrence decreased by 17% (de Dassel et al. 2018). These results provide a rationale for a focus on ensuring clients receive at least 40% of their prescribed doses, with 80% or more of doses as an adherence target.

There are limited data about ways to improve adherence, and the findings are often highly specific to the study population (Rémond et al. 2016). Australian attempts to improve adherence have had limited success. A randomised control trial conducted between 2013 and 2016 involved communities in the Northern Territory, where clinics received multicomponent intervention supporting activities to improve penicillin delivery (Ralph et al. 2018). The outcome of the trial was that quality improvement and chronic care models intended to improve delivery of penicillin prophylaxis did not improve penicillin adherence.

A study, conducted with 29 Aboriginal children and 59 clinicians, aimed to explore the experiences of First Nations children receiving penicillin injections for rheumatic fever prevention. Findings revealed that while some First Nations children adapted to the pain of the injections, others struggled significantly, with a few even feeling unwell post-injection. Clinicians, although aware of pain reduction techniques, did not consistently apply them, and all the clinicians found the process distressing. The study highlights the urgent need for supportive policies and guidelines to better the experiences of both the children and the clinicians. The study also highlights the potential benefits of establishing supportive relationships within local communities for young individuals deterred by the pain, given their elevated risk of heart valve damage. The study identifies the need for further research on pain alleviation methods, potential non-allergic adverse effects of the injections, and the exploration of alternative treatments (Mitchell et al. 2018).The importance of multidisciplinary teams and patient-centred and culturally safe care for maximising adherence has been recommended in the 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of ARF and RHD (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2020).

It has been suggested that the introduction of specialist ARF/RHD nurse practitioners in Australia could help to improve service delivery and patient outcomes (RHDAustralia 2015).

Screening

Diagnosis of all cases of ARF and RHD continues to be a challenge for the control and prevention strategies in place in Australia. Underdiagnosis of RHD and ARF is well recognised. A recent study in Maningrida (in the Northern Territory) of echocardiographic screening among young First Nations people aged 5–20 found there was a large burden of undiagnosed RHD in this group (Francis et al. 2020). While acknowledging that echocardiographic screening in remote communities can sometimes not be cost-effective, the authors recommended its use be considered in some remote communities where passive case-finding for ARF and RHD might be inadequate. The study had a high participation rate (72%) which was attributed to its focus on education and health promotion in local languages, extensive community engagement and local leadership (Carapetis & Brown 2020).

Variable ascertainment of diagnosed cases in RHD Registers may reduce the usefulness of the RHD control program (McDonald et al. 2005), and skew the study of ARF and RHD, limiting the ability for the effect of interventions to be monitored and for trends to be detected. Linked administrative data was used to compare case ascertainment in ARF/RHD register records and hospital records from the Northern Territory, South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia (Agenson et al. 2020). Of the 5,824 records for First Nations patients identified, 31% were present in the hospital data but absent from the registers data, and 26% were present in the registers data but absent from the hospitals data. The percentages of hospital-diagnosed ARF/RHD cases recorded on ARF/RHD registers varied across jurisdictions. The percentages of ARF cases captured in both records ranged between 68% (in Queensland) and 77% (in the Northern Territory), while for RHD the percentages ranged between 21% (in South Australia) and 51% (in Queensland). There are differences between characteristics of cases in registers compared with hospital records. The cases captured in the register, as a proportion of all identified cases, are younger, more often First Nations people and more often reside in Northern Australia. It is likely that a focus on active case finding among high-risk population groups from the RHD programs has resulted in the registers capturing information about cases where prevention strategies will be most effective. Careful consideration of how elimination efforts will be affected by incomplete ascertainment of older, non-Indigenous and metropolitan based cases by RHD registers is required, with commensurate actions associated with calls to strengthen registers.

Evaluations and strategies for RHD

The role of registers in the Australian context was affirmed in the 2017 Evaluation of the RFS (Health Policy Analysis 2017), conducted between October 2016 and December 2016. The evaluation noted that more work was needed to refine the state-based programs, to overcome challenges in areas such as staff retention, education, and training, and in the collection, use and reporting of data on the registers. Streamlined governance and data systems were recommended as integral in assisting agency collaboration to deliver environmental prevention programs, which are fundamental to successful interventions (Link & Phelan 1995). The evaluation also found several key achievements of the RFS such as increased awareness in areas where ARF and RHD are prevalent, an increased number of people on the registers and prescribed prophylactic injections, and improvements in adherence to secondary prophylaxis, especially in the Northern Territory and South Australia, which assists in preventing disease progression (Health Policy Analysis 2017).

The Australian Government Rheumatic Fever Strategy funds RHD Control Programs to support detection and management of ARF and RHD. A report assessing epidemiological changes during the years of RHD Control Program operation has concluded that RHD Control Programs have contributed to major success in the management of ARF/RHD through increased delivery of secondary prophylaxis and disease progression has remained low and stable over the period 2010–2017. Despite these gains, the volume of new ARF notifications and newly registered RHD patients increased annually. Control programs that support primary care services to deliver secondary prevention measures remain critical infrastructure for those already living with ARF and RHD (Stacey et al. 2023).

The END RHD Communities model is a collaborative approach to reducing RHD in high-risk First Nations communities. Qualitative research indicates that First Nations people want help, such as help to navigate health systems, help to understand their health (and their family’s health), and support that could mitigate the effects of high health care staff turnover. Central to the model is the employment of Aboriginal community workers who develop partnerships with individuals and families who are at highest risk of ARF and RHD, and then assist them to navigate the health-care system, increase their self-management capacity and manage environmental risk factors (Thomas et al. 2017).

The Champions4Change program is an RHD awareness raising and advocacy program tailored for First Nations people affected by ARF and RHD. It was evaluated for its effectiveness in bridging the gap between scientific knowledge and First Nations cosmologies (worldviews). The evaluation revealed that the program’s success stories were rooted in its culturally and locally appropriate approaches. By leveraging the lived experiences of First Nations peoples with ARF/RHD, the program was able to enhance community knowledge and awareness of RHD. Furthermore, the emphasis on understanding and respecting First Nations worldviews proved pivotal in fostering trust and engagement within First Nations communities. The program’s approach, which prioritised cultural safety and empowerment, was instrumental in its positive impact on First Nations health outcomes related to RHD (Wade & Stewart 2022).

Implications

ARF and RHD are preventable diseases of disadvantage and the burden of RHD is highest among people living in poor-quality housing, and rural areas where access to health-care services is limited (Hardie & de Dassel 2019; RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022). Rates of ARF and RHD among First Nations people in Australia are among the highest in the world and large disparities exist between First Nations people and other Australians (AIHW 2013).

In 2018, the World Health Organization (WHO) prioritised the global control of ARF and RHD, emphasising the need for innovative solutions for prevention, improved access to health care and enhanced surveillance of this preventable disease. Effective early intervention can prevent premature mortality from RHD. There are 3 levels of prevention for RHD: reducing the risk factors for ARF (primordial prevention); primary prevention of ARF and RHD; and secondary prevention (prophylaxis) of ARF and RHD. Primordial prevention aims to avoid episodes of streptococcal pharyngitis by tackling poverty, improving living and housing standards, and increasing access to health care. Most of the observed trends in reductions in prevalence of RHD globally are due to primordial prevention. Primary prevention of ARF can be achieved through the effective treatment of streptococcal pharyngitis with penicillin and is most effective when delivered as part of routine child health care and integrated into existing health strategies and community programs. Compared with culture of throat swabs, rapid antigen-detection tests offer diagnosis at the point-of-care and therefore need to be part of such strategies. For countries where RHD is endemic the main strategies for prevention, control and elimination include: improving standards of living; expanding access to appropriate care; ensuring a consistent supply of quality-assured antibiotics for primary and secondary prevention; and planning, development and implementing feasible programs for prevention and control of RHD, supported by adequate monitoring and surveillance, as an integrated component of national health system responses (World Health Organisation 2018). There is currently no vaccine against GAS infection and no cure for RHD (Katzenellenbogen et al. 2020).

In Australia, provision of culturally appropriate education for communities on the causes of ARF and RHD and the health implications is needed. Early detection and management for individuals living with ARF and RHD are important for preventing recurrences, ensuring adherence to treatment, and preventing the impact of RHD. High hospital admissions among First Nations young people highlights the need for a health workforce with skills to provide paediatric and adolescent hospital care which meets the needs of First Nations children and their families (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022).

RHD registers are a central element of secondary disease prevention programs to prevent recurrence of ARF and reduce the occurrence or severity of RHD through informing control programs, case detection and treatment compliance activities. The Australian RHD registers contribute to improved case detection and are the most effective way of supporting treatment adherence and enhancing clinical follow-up of people with RHD. An indicator system to monitor secondary prophylaxis rates has been effectively utilised in the Northern Territory.

Interpretation of the differing trends in incidence of ARF and RHD across the jurisdictions requires caution. The data contained in the registers are reliant on the completion of notifications of ARF and RHD diagnoses by health professionals. Improved case ascertainment in the registers and improved accuracy of disease estimates would result in greater understanding of the epidemiology of ARF and RHD. Register data may be volatile between years. Research has shown the potential for a large burden of undiagnosed cases, and comparisons across jurisdictions must be taken with caution when there are different notification and registration practices. When they are functioning with complete and timely data, registers would have a role in monitoring the impact of interventions at each preventative stage.

Improving and maintaining high levels of secondary prophylaxis with regular penicillin injections is vital to preventing ARF recurrences and the development of RHD. However, despite ongoing efforts by patients and their families, primary health-care providers and the control programs, rates of delivery of secondary prophylaxis in some settings remain inadequate. Improved engagement between health-care services and First Nations patients, and strategies to support adherence that are culturally appropriate and age appropriate are needed (Ralph et al. 2018). The use of social media, incentives, peer-support groups, innovative staff education and retention measures, and community support personnel employed to help people navigate the health-care system, need to be developed and expanded. Targeted interventions, outreach programs, the use of local First Nations Health Workers, education and health promotion in local languages, extensive community engagement and local leadership should be utilised in both primary and secondary prevention initiatives. Local approaches could also assist with addressing the personal factors that are potentially associated with poor adherence, such as pain caused by injections and injection refusal (AIHW 2019; Parnaby & Carapetis 2010).

ARF and RHD are uncommon diseases in most places in Australia, so many health professionals have poor awareness and knowledge about them, and the ongoing vigilance required, particularly regarding the long-term needs of patients. Health professionals commencing work in remote areas should undergo training to engender greater knowledge and awareness of ARF and RHD, and patients’ needs. Increasing awareness of ARF and RHD among health professionals, patients and their families and communities, is one of the aims for the RFS.

There are limitations to the impact secondary prevention can have when pursuing elimination of ARF and RHD in Australia. Primordial and primary prevention strategies which focus on upstream determinants of health (Cannon et al. 2019) remain vital and should be developed further and strengthened. For example, poor housing conditions such as overcrowding and poor functioning of ‘health hardware’ are conducive to the transmission and recurrence of infectious diseases such as scabies. Reducing the negative effects of household crowding is consistently identified as one of the major health priorities for First Nations people and peak bodies (Melody et al. 2016). Improvements in living conditions are acknowledged as key drivers of RHD elimination in developed countries, including the elimination of the disease for most of Australia’s non-Indigenous population. Housing and environmental health policies should be considered to be critical enablers for any RHD elimination strategy (Brown et al. 2007; Watkins et al. 2017). For more on overcrowding see measure 2.01 Housing, and for more on ‘health hardware’ and the healthy living practices that enable households to manage infectious disease and environmental health risks see measure 2.02 Access to functional housing with utilities.

The Health Plan supports community driven housing and infrastructure solutions (Objective 7.2) and encourages housing providers to consider targeted primordial intervention for housing-related medical conditions that are common to First Nations households, such as ARF and RHD, trachoma, and otitis media. The Health Plan also includes Priority 5 – Early Intervention; which emphasises place-based approaches that are locally determined such as preventing ARF from becoming RHD where needed, and promotes enhancing access to culturally safe and responsive, best practice early intervention (Objective 5.3) (Department of Health and Aged Care 2021).

Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health services for First Nations people. ACCHSs are operated across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. Ensuring services are accessible and appropriate is important to drive reductions in rates of ARF and RHD. The Australian Government has committed to building a strong and sustainable Aboriginal community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people. The Health Plan also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism, provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Endgame Strategy sets out the priority areas needed to eliminate RHD and emphasised resourcing First Nations leadership and communities to tackle the root causes of RHD, improve housing and living conditions, establish comprehensive GAS prevention and control in high-risk communities, and improve the health and wellbeing of those living with ARF and RHD. With the launch of the Endgame Strategy, the future focus of ARF and RHD control also includes primordial and primary prevention strategies that reduce childhood GAS infections, with the goal of preventing these diseases (Wyber et al. 2020a; Wyber et al. 2020b).

Working in partnership with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO), the Australian Government has established new national governance arrangements for the Australian Government’s RFS. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap is the foundation of this new approach, with particular emphasis on Priority Reform One (formal partnership and shared decision making). The new arrangement is designed to harness the expertise of representatives across multiple sectors to provide advice on a nationally integrated and coordinated approach to addressing ARF and RHD in First Nations communities. This new governance structure reflects the need for a whole of government and community effort. This includes establishment of the RFS Joint Advisory Committee in 2022, to guide coordination and implementation of the RFS, and informed by the Endgame Strategy. The RFS Joint Advisory Committee includes representation from state and territory governments, ACCHSs, peak health organisations, and First Nations RHD clinical experts. NACCHO will work alongside the Aboriginal community-controlled sector to develop a new service delivery model for the prevention and treatment of ARF and RHD. This model will support community-controlled and community-led actions to address these preventable conditions which are strongly influenced by poor housing and the social determinants of health. These reforms are supporting actions on the ground to address ARF and RHD in affected communities, and give practical effect to the National Agreement on Closing the Gap to which all Australian governments have committed.

The Australian Government selected 7 ACCHSs in locations with high prevalence of ARF and RHD to develop and deliver a pilot program focused on primordial and primary prevention of ARF and RHD. The design of the pilot programs focused on implementing primordial and primary prevention services where the social determinant factors as described above are significant, broad and complex. The pilot projects underwent evaluation (not yet published) which was approached through a co-design process with input provided from each participating ACCHS involved in the pilot project, including Rheumatic Heart Disease Australia (RHDA) and the Australian Government. The evaluation, which measured the impact of the pilot programs, recommended: that a comprehensive national model be implemented at the local level; provision of long-term funding for a trial of the model using a selection of providers; the incorporation of good data collection; and monitoring practices to demonstrate the effectiveness of the program in achieving expected outcomes.

In March 2022, the latest edition (3.2) of The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease was released by RHD Australia and includes a new focus which places people with ARF and RHD, and their families and communities, at the centre of care. The guidelines were written by clinical and public health experts, researchers, and policymakers, and developed in collaboration with key stakeholders and an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander advisory group. The guidelines contain standards, recommendations, and guidance for providing clinically sound and culturally safe care to people living with ARF and RHD (RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022).

The Policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2021a. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2021b. National, state and territory population. Canberra: ABS.

- Agenson T, Katzenellenbogen JM, Seth R, Dempsey K, Anderson M, Wade V et al. 2020. Case ascertainment on Australian registers for acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. International journal of environmental research and public health 17:5505.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2013. Rheumatic heart disease and acute rheumatic fever in Australia: 1996-2012. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2019. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia web report. Cat. no: CVD 86. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2020. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia 2014–2018. Cat. no: CVD 88. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018: Interactive data on risk factor burden among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2023. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia 2017-2021. Canberra: AIHW.

- Ali SH, Foster T & Hall NL 2018. The Relationship between Infectious Diseases and Housing Maintenance in Indigenous Australian Households. International journal of environmental research and public health 15.

- Brown A, McDonald MI & Calma T 2007. Rheumatic fever and social justice. The Medical Journal of Australia 186:557-8.

- Cannon J, Bessarab DC, Wyber R & Katzenellenbogen JM 2019. Public health and economic perspectives on acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. The Medical Journal of Australia 211:250-2. e1.

- Carapetis JR & Brown A 2020. Community leadership and empowerment are essential for eliminating rheumatic heart disease. The Medical Journal of Australia 213:116-7.

- Chamberlain-Salaun J, Mills J, Kevat P, Remond M & Maguire G 2016. Sharing success - understanding barriers and enablers to secondary prophylaxis delivery for rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. 27581750.

- Coffey P, Ralph A & Krause V 2018. The role of social determinants of health in the risk and prevention of group A streptococcal infection, acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease: a systematic review. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 12:e0006577.

- de Dassel J, de Klerk N, Carapetis J & Ralph A 2018. How many doses make a difference? An analysis of secondary prevention of rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Journal of the American Heart Association 7:e010223.

- Department of Health and Aged Care 2021. The new National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care.

- Francis JR, Fairhurst H, Hardefeldt H, Brown S, Ryan C, Brown K et al. 2020. Hyperendemic rheumatic heart disease in a remote Australian town identified by echocardiographic screening. Medical Journal of Australia.

- Hamsanathan P, Katzenellenbogen J, Andrews D, Carapetis J, Richmond PC, McKinnon E et al. 2023. A Review of Cardiac Surgical Procedures and Their Outcomes for Paediatric Rheumatic Heart Disease in Western Australia. Heart Lung and Circulation 32:1271-410.

- Hardie K & de Dassel J 2019. Beyond Secondary Prevention of Rheumatic Heart Disease. Canberra: Public Health Association.

- Hardie K, Ralph A & de Dassel J 2020. RHD elimination: action needed beyond secondary prophylaxis. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health.

- Haynes E, Mitchell A, Enkel S, Wyber R & Bessarab D 2020. Voices behind the Statistics: A Systematic Literature Review of the Lived Experience of Rheumatic Heart Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17.

- He VY, Condon J, Ralph A, Zhao Y, Roberts K, de Dassel J et al. 2016. Long-Term Outcomes From Acute Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease: A Data-Linkage and Survival Analysis Approach. Circulation 134:222-32.

- Health Policy Analysis 2017. Evaluation of the Commonwealth Rheumatic Fever Strategy – Final report. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health.

- Katzenellenbogen JM, Bond-Smith D, Seth RJ, Dempsey K, Cannon J, Stacey I et al. 2020. Contemporary Incidence and Prevalence of Rheumatic Fever and Rheumatic Heart Disease in Australia Using Linked Data: The Case for Policy Change. J Am Heart Assoc 9:e016851.

- Kerrigan V, Kelly A, Lee AM, Mungatopi V, Mitchell AG, Wyber R et al. 2021. A community-based program to reduce acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in northern Australia. BMC Health Serv Res 21:1127.

- Link BG & Phelan J 1995. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of health and social behavior:80-94.

- May PJ, Bowen AC & Carapetis JR 2016. The inequitable burden of group A streptococcal diseases in Indigenous Australians. The Medical Journal of Australia 205:201-3.

- McDonald M, Brown A, Noonan S & Carapetis J 2005. Preventing recurrent rheumatic fever: the role of register based programmes. Heart 91:1131.

- Melody SM, Bennett E, Clifford HD, Johnston FH, Shepherd CCJ, Alach Z et al. 2016. A cross-sectional survey of environmental health in remote Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. Int J Environ Health Res 26:525-35.

- Menzies School of Health Research 2023. Rheumatic heart disease. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- Michael GB, Mary YM, Maylene S-K, Andrea B, Asha CB, Geetha PB et al. 2023. Research priorities for the primordial prevention of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease by modifying the social determinants of health. BMJ Global Health 8:e012467.

- Mitchell A, Belton S, Johnston V, Read C, Scrine C & Ralph A 2018. Aboriginal children and penicillin injections for rheumatic fever: how much of a problem is injection pain? Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 42:46-51.

- Northern Territory Government 2020. Scabies. Viewed 30 September 2020.

- Parnaby MG & Carapetis JR 2010. Rheumatic fever in indigenous Australian children. Journal of paediatrics and child health 46:527-33.

- Pickering JL, Barth DD & Bowen AC 2020. Performance and Practicality of a Rapid Molecular Test for the Diagnosis of Strep A Pharyngitis in a Remote Australian Setting. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene:tpmd200341.

- Ralph A 2020. What is Acute Rheumatic Fever? Darwin: RHDAustralia. Viewed 6 October 2020.

- Ralph A, De Dassel J, Kirby A, Read C, Mitchell A, Maguire G et al. 2018. Improving delivery of secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic heart disease in a high‐burden setting: outcome of a stepped‐wedge, community, randomized trial. Journal of the American Heart Association 7:e009308.

- Ralph AP, Kelly A, Lee AM, Mungatopi VL, Babui SR, Budhathoki NK et al. 2022. Evaluation of a Community-Led Program for Primordial and Primary Prevention of Rheumatic Fever in Remote Northern Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 19.

- Rémond MG, Coyle ME, Mills JE & Maguire GP 2016. Approaches to improving adherence to secondary prophylaxis for rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease. Cardiology in Review 24:94-8.

- RHDAustralia 2015. Framework for a nurse practitioner role in ARF RHD (National RHD Australia). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2020. The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3rd edition). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- RHDAustralia ARF/RHD writing group 2022. The 2020 Australian guideline for prevention, diagnosis and management of acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease (3.2 edition, March 2022). Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, Kama M, Wand H, Tikoduadua L et al. 2017. The epidemiology of scabies and impetigo in relation to demographic and residential characteristics: baseline findings from the skin health intervention Fiji trial. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 97:845-50.

- Smith MT, Zurynski Y, Lester-Smith DE, E. & Carapetis J 2012. Rheumatic fever. Australian Journal for General Practitioners 41:31-5.

- Stacey I, Hung J, Cannon J, Seth RJ, Remenyi B, Bond-Smith D et al. 2021. Long-term outcomes following rheumatic heart disease diagnosis in Australia. Eur Heart J Open 1:oeab035-oeab.

- Stacey I, Ralph A, de Dassel J, Nedkoff L, Wade V, Francia C et al. 2023. The evidence that rheumatic heart disease control programs in Australia are making an impact. Aust N Z J Public Health 47:100071-.

- Telethon Kids Institute 2020. Six-minute Strep A tests dramatically cut wait time in remote settings. Viewed 2 October 2020.

- Thomas S, Crooks K, Taylor K, Massey PD, Williams R & Pearce G 2017. Reducing recurrence of bacterial skin infections in Aboriginal children in rural communities: new ways of thinking, new ways of working. Aust J Prim Health 23:229-35.

- Wade V & Stewart M 2022. Bridging the gap between science and indigenous cosmologies: Rheumatic Heart Disease Champions4Change. Microbiology Australia 43:89-92.

- Watkins DA, Johnson CO, Colquhoun SM, Karthikeyan G, Beaton A, Bukhman G et al. 2017. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Rheumatic Heart Disease, 1990–2015. N Engl J Med 377:713-22.

- World Health Organisation 2018. Seventy-first World Health Assembly update, 25 May. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Wyber R, Kelly A, Lee AM, Mungatopi V, Kerrigan V, Babui S et al. 2021. Formative evaluation of a community-based approach to reduce the incidence of Strep A infections and acute rheumatic fever. Aust N Z J Public Health 45:449-54.

- Wyber R, Noonan K, Halkon C, Enkel S, Ralph A, Bowen A et al. 2020a. The RHD Endgame Strategy: The blueprint to eliminate rheumatic heart disease in Australia by 2031. Perth.

- Wyber R, Noonan K, Halkon C, Enkel S, Cannon J, Haynes E et al. 2020b. Ending rheumatic heart disease in Australia: the evidence for a new approach. The Medical Journal of Australia 213:S3-S31.