Key facts

Why is it important?

Housing is an important environmental factor for health and wellbeing. Functional housing encompasses basic facilities, infrastructure and habitability. These factors combined enable households to carry out healthy living practices including waste removal; maintaining cleanliness through washing people, clothing and bedding; managing environmental risk factors, such as electrical safety and temperature in the living environment; controlling air pollution for allergens; reducing the negative impacts of overcrowding; and preparing and storing food safely (Bailie & Wayte 2006; FaCSIA 2007; Nganampa Health Council et al. 1987; NSW Department of Health 2019).

The equipment needed for these healthy living practices, known as ‘health hardware’, is critically important and needs regular maintenance to remain effective such as, safe electrical systems, toilets, showers, taps, sinks, kitchen cupboards and benches, stoves, ovens and fridges. It has been estimated that around 70% of the work required to improve health hardware in houses is due to a lack of routine maintenance (Lea & Torzillo 2016).

Overcrowding, poorly maintained infrastructure and inadequate basic facilities can lead to the spread of infectious and bacterial diseases such as skin infections, respiratory disease, otitis media (Jervis-Bardy et al. 2014; NSW Department of Health 2010), trachoma and acute rheumatic fever (see measures 1.15 Ear Health, 1.16 Eye health, 1.06 Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease, and 2.01 Housing). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to live in poor quality housing (Baker et al. 2016) and are more likely to experience these resulting health effects.

Data findings

The 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey collected data on household facilities and structural problems. In 2018–19, 80% of Indigenous households were living in houses of an acceptable standard (households with 4 working facilities for washing people, clothes/bedding, storing/preparing food and sewerage and not more than 2 major structural problems).

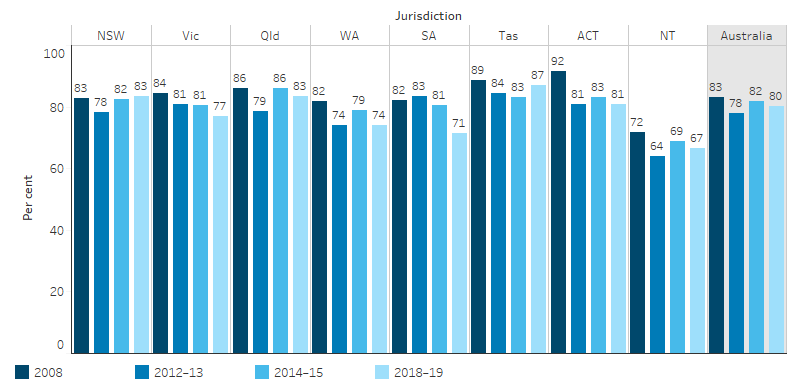

The proportion of Indigenous households living in houses of an acceptable standard was similar in 2012–13 (78%) and 2018–19 (80%). In 2018–19, the highest proportion of people living in houses of an acceptable standard was in Tasmania (87%), and the lowest was in the Northern Territory (67%) (Table D2.02.6, Figure 2.02.1).

Figure 2.02.1: Proportion of Indigenous households living in houses of an acceptable standard, by state/territory, 2008, 2012–13, 2014–15 and 2018–19

Source: Table D2.02.6. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2008 and 2014; Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2012–13 (2012–13 NATSIHS component); and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

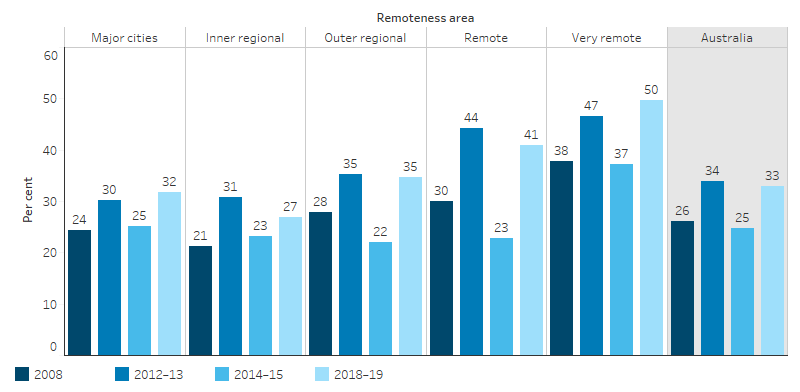

In 2018–19, 33% of Indigenous households were living in dwellings with major structural problems (including problems such as sinking/moving foundations, sagging floors, wood rot/termite damage and roof defects). This was similar to the proportion in 2012–13 (34%).

In 2018–19, in Very remote areas, 50% of Indigenous households were living in dwellings with major structural problems compared with 32% of households in Major cities (Table D2.02.5, Figure 2.02.1).

Figure 2.02.2: Proportion of Indigenous households in dwellings with major structural problems by remoteness, 2008, 2012–13, 2014–15 and 2018–19

Source: Table D2.02.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2008 and 2014–15; Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2012–13 (2012–13 NATSIHS component); and National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

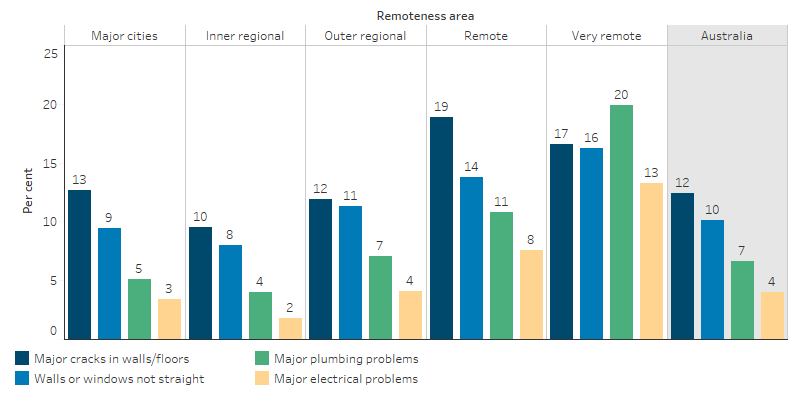

Just over 1 in 10 Indigenous households (12%) were living in dwellings with major cracks in walls/floors. This was the most common structural problem for Indigenous households in both Non-remote (12%) and Remote areas (18%). In Very remote areas, dwellings with plumbing problems (20%), electrical problems (13%) and walls or windows not straight (16%) also represented major issues for health and safety within homes (Table D2.02.2, Figure 2.02.3).

Figure 2.02.3: Proportion of Indigenous households in dwellings with major structural problems, by selected problems and remoteness, 2018–19

Source: Table D2.02.2. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

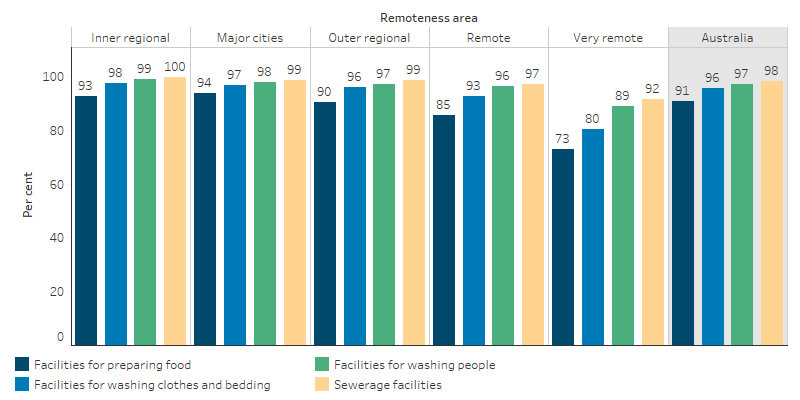

Facilities that support healthy living practices include sewerage, washing (people and clothes/bedding) and food preparation/storage.

In 2018–19, among Indigenous households:

- 91% reported having working facilities for storing/preparing food

- 96% reported having working facilities for washing clothes/bedding

- 97% reported having working facilities for washing people

- 98% reported having working sewerage facilities (Table D2.02.7, Figure 2.02.4).

In Remote areas, 79% of Indigenous households reported having working facilities for preparing food, compared with 93% in Non-remote areas. Of Indigenous households in Remote areas, 86% reported having working facilities for washing clothes and bedding, compared with 97% of households in Non-remote areas (Table D2.02.7).

Figure 2.02.4: Proportion of Indigenous households reporting working facilities for healthy living practices by, remoteness, 2018–19

Source: Table D2.02.7. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

The Northern Territory was the jurisdiction with the lowest proportion of households reporting working food preparation facilities (79%), working washing facilities for clothes/bedding (85%), working facilities for washing people (91%) and working sewerage facilities (93%) (Table D2.02.8).

Research and evaluation findings

Internationally, research has demonstrated that improving the internal quality of dwellings can facilitate outcomes particularly in the general health, respiratory health and mental health of occupants (Baker et al. 2013).

Housing programs need to be accompanied by hygiene promotion, and social, behavioural and environmental interventions to support health outcomes (Bailie et al. 2011; Bailie et al. 2012).

Improved knowledge of personal finances can be a crucial enabler towards improved ‘health hardware’ for households. A recent project undertaken in Remote Indigenous communities explored the positive influence on the wellbeing of clients and staff when culturally supportive financial services were provided to their Indigenous clients. These services resulted in clients redirecting their spending to purchase household items such as washing machines, fridges and mattresses leading to reports of better health outcomes(Godinho et al. 2018).

Children who live in a dwelling that is badly deteriorated have been found to have poorer physical health outcomes and social and emotional wellbeing compared with those growing up in a dwelling in excellent condition (Baker et al. 2013). Comparisons between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children in the Longitudinal Study of Australian Children show that improvements in housing can be expected to translate into gains for Indigenous children’s health social, and learning outcomes (Dockery et al. 2013).

The Housing for Health (HFH) program addresses health hardware functionality as a way to support 9 ‘Healthy Living Practices’, which are the ’key things people need to be able to do if their house is to contribute to, rather than harm, their health’ (Lea & Torzillo 2016). HFH programs have been implemented in a variety of locations around Australia. The results of a HFH project in a Remote Aboriginal community in South Australia found that carrying out minor repairs and maintenance was associated with decreased rates of eye and skin infections in people of all ages (DoHA 2007). In New South Wales an evaluation of the HFH program found that those who received the HFH intervention had a significantly reduced rate of hospital separations for infectious diseases — 40% less than the hospital separation rate for the rest of the rural New South Wales Aboriginal population without the HFH interventions (NSW Department of Health 2010, 2019).

The evaluations of two programs based on HFH verify the positive link between functioning health hardware and the health of residents. The Fixing Houses for Better Health (FHBH) program was based on the HFH methodology and involved surveying houses and performing basic maintenance simultaneously by an Aboriginal Survey Fix team, with licensed tradespersons completing additional work as soon as possible. Ongoing case series evaluation of FHBH occurred between July 2001 and June 2005, with 1,419 houses surveyed in 42 communities. Pre- and post-surveys showed there had been improvements in safe electrical systems, and functioning toilets and showers. The Housing and Environmental Health survey involved annual housing surveys conducted in three different Remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory (Hardy 2002). The approach was based on the HFH methodology with community survey teams surveying each house and advising community tradespeople of work required. The evaluation showed one community had improvements in safety and functioning of washing, sanitation and food preparation and storage facilities, and this was reported to be associated with a decrease in health centre attendances (DoHA 2007).

The Australian Government published the findings of a review of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH) and the Remote Housing Strategy in 2017. The review notes that by 2018, the strategy would have delivered over 11,500 more liveable homes in Remote Australia, and this was estimated to have led to a significant decrease in the proportion of overcrowded households. The NPARIH had an increased emphasis on systematic property and tenancy management with outcome payments to jurisdictions for more regular property inspections, improved maintenance plans, and the completion of repairs within agreed timeframes.

Recommendations from the review of the NPARIH included recurrent housing maintenance; investment for an additional 5,500 houses by 2028; equal sharing of program costs between the Commonwealth and jurisdictions; regional governance structures; improved transparency; performance frameworks and information processes; a minimum five-year rolling plan for the program, property certification reporting, appropriate building and certification standards; and local workforce development. The review also included an assessment of performance against five issues in Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. The issues were new house builds; refurbishments; housing quality; cyclical maintenance; and community engagement, employment and business initiatives. Quantitative targets for both new builds and refurbishments were met in each jurisdiction, except new builds in Western Australia. Qualitative assessments showed good performance across each issue in Queensland, poor performance across each in Western Australia, and a range of good to poor performance in South Australia and the Northern Territory.

Implications

Programs and interventions targeted at improving the quality of housing can lead to positive health outcomes. Regular maintenance of the health hardware in housing is required for housing to remain functional and reduce housing-related health risks.

In addition to recognising the direct impact of basic housing conditions on health, interventions must also recognise the features of housing that indirectly influence health and wellbeing outcomes. For example, location, affordability, housing tenure, access to employment networks, and empowerment through education can indirectly impact the health and wellbeing of occupants (Dockery et al. 2013). Housing policy, program design and implementation should be aware of this broader context.

Sub-standard housing is an issue in Non-remote areas as well as Remote areas (Andersen et al. 2017). As Non-remote areas contain both the majority of Indigenous Australians and the majority of the burden of disease for Indigenous Australians, housing standards in Non-remote areas should also be considered in program design (AIHW 2016).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2016. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2011: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- Andersen MJ, Williamson AB, Fernando P, Wright D & Redman S 2017. Housing conditions of urban households with Aboriginal children in NSW Australia: tenure type matters. BMC Public Health 18:70.

- Bailie RS, McDonald EL, Stevens M, Guthridge S & Brewster DR 2011. Evaluation of an Australian indigenous housing programme: community level impact on crowding, infrastructure function and hygiene. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 65:432.

- Bailie RS, Stevens M & McDonald EL 2012. The impact of housing improvement and socio-environmental factors on common childhood illnesses: a cohort study in Indigenous Australian communities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 66:821-31.

- Bailie RS & Wayte KJ 2006. Housing and health in Indigenous communities: key issues for housing and health improvement in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Australian Journal of Rural Health 14:178-83.

- Baker E, Lester L, Beer A, Mason K & Bentley R 2013. Acknowledging the health effects of poor quality housing: Australia’s Hidden Fraction. Urban and Regional Planning, the University of Adelaide.

- Baker E, Lester LH, Bentley R & Beer A 2016. Poor housing quality: Prevalence and health effects. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 44:219-32.

- FaCSIA (Department of Family and Community Services) 2007. National Indigenous Housing Guide, 3rd Edition. (ed., Department of Social Services). Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Dockery AM, Ong R, Colquhoun S, Li J & Kendall G 2013. Housing and children’s development and wellbeing: evidence from Australian data. Melbourne: AHURI.

- DOHA (Australian Government Department Health) 2007. Evidence of Effective Interventions to Improve the Social and Environmental Factors Impacting on Health - Informing the development of Indigenous Community Agreements. Canberra: Australian Government Department Health. Viewed 25/8/20.

- Godinho V, Eccles K & Thomas L 2018. Beyond Access: The role of microfinance in enabling financial empowerment and wellbeing for Indigenous clients: lessons from remote Australia. Third Sector Review 24:57.

- Hardy B 2002. A report on simple, low cost, effective house survey and repair programs in the Northern Territory, Australia Journal of Rural and Remote Environmental Health 1:19 to 22.

- Jervis-Bardy J, Sanchez L & Carney AS 2014. Otitis media in Indigenous Australian children: review of epidemiology and risk factors. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 128 Supplement S1:S16-27.

- Lea T & Torzillo P 2016. The cunning of data in Indigenous housing and health. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community 44:272-82.

- Nganampa Health Council, South Australia Committee of Review on Environmental and Public Health within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands in South Australia, South Australian Health Commission & Aboriginal Health Organisation of South Australia 1987. Report of Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku: An Environmental and Public Health Review within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands. Adelaide.

- NSW Department of Health 2010. Closing the Gap: 10 Years of Housing for Health in NSW - An evaluation of a healthy housing intervention. (ed., Department of Health - NSW). Sydney: DoH-NSW.

- NSW Department of Health 2019. Housing for Health. Viewed 20/08/2019.