Key messages

- In 2021, based on the ABS Census of Population and Housing 42% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households owned their home (with or without a mortgage), 56% were renting, other tenure accounted for the remaining 1.6%. Home ownership rates were lower for Indigenous households than other households (42% compared with 68%).

- The proportion of Indigenous households that owned their own home (with or without a mortgage) increased from 37% in 2011 to 42% in 2021, and the gap in the home ownership rate between Indigenous and other households decreased from 32 to 26 percentage points.

- At 30 June 2022, there were around 38,251 Indigenous households in public housing, 13,424 in State Owned and Managed Indigenous housing, and 11,210 in community housing. There were also 16,281 households living in Indigenous community housing.

- Of the 83,000 of Indigenous households who owned their home with a mortgage based on the 2021 Census, 14% (11,800) were spending more than 30% of their gross income on mortgage repayments. Among Indigenous households who were renting (169,500), over 1 in 3 (35%) were spending more than 30% of their gross income on rent payments (58,900).

- In 2021, 81.4% of Indigenous Australians lived in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing – an increase from 74.6% in 2011.

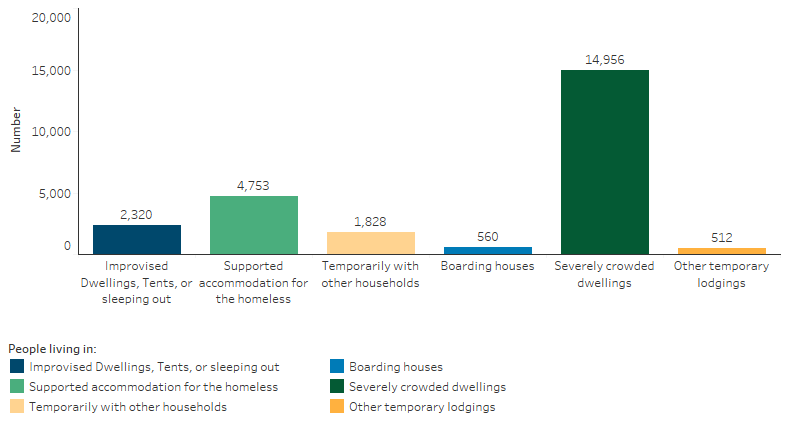

- Estimates from the 2021 Census indicate that around 24,900 Indigenous Australians were homeless on Census night (3.1% of the Indigenous population). The homelessness rate for Indigenous Australians was 8.8 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians in 2021 (307 compared with 35 per 10,000 population).

- Among Indigenous Australians experiencing homelessness, 60% were living in severely crowded dwellings (15,000), 19% were in supported accommodation for the homeless (4,800), 9% were in improvised dwellings, tents or sleeping out (2,300), and the remainder were staying temporarily with other households, living in boarding houses, or living in other temporary lodgings.

- In the decade to 2021, the rate of homelessness among the Indigenous population declined from 487 to 307 per 10,000 population, driven by a decline in people living in severely overcrowded dwellings. The gap in homelessness rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians also declined (from 453 to 272 per 10,000 population).

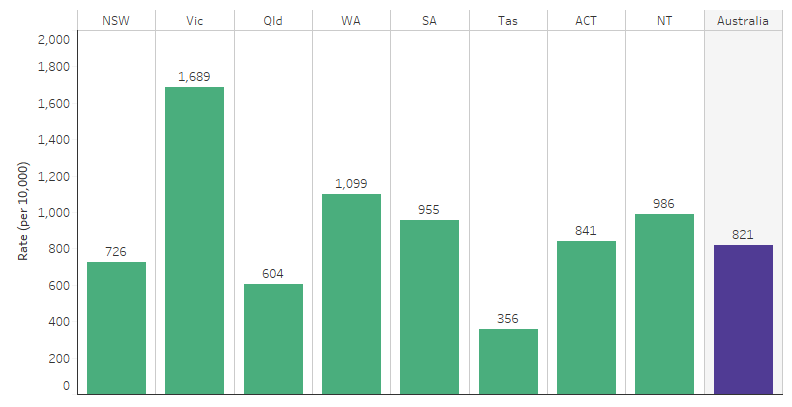

- In 2021–22, around 72,900 Indigenous Australians received support from specialist homelessness services (SHS), a rate of 821 per 100,000 population. At the end of support more Indigenous clients were living in housing with some form of tenure, this was mainly an increase in clients living in public or community housing (from 31% to 38%).

- Findings from the House of Representatives Standing Committee Inquiry into Homelessness highlighted the effectiveness and appropriateness of Aboriginal community-controlled housing services, and recommended the development of a national integrated approach to housing and homelessness services for Indigenous Australians.

- Remote housing programs have delivered improvements, but the persistent high rate of overcrowding in remote areas show there are still advances to be made.

Why is it important?

Stable and secure housing is fundamentally important to health and wellbeing (AIHW 2019a). Housing circumstances—such as tenure, affordability, the amount of living space and location—are key determinants of physical and mental health (Foster et al. 2011; Marsh et al. 2000). However, causal relationships between poor housing and poor health are complex, and directionality is not always clear. For example, poor housing circumstances can contribute to poor health, and poor health can result in households living in worse housing circumstances (Brackertz & Wilkinson 2017).

There are also indirect relationships between housing circumstances, health and socioeconomic factors such as education, income and employment (Thomson et al. 2013). For example, overcrowding, insecure housing tenure and homelessness have been found to adversely affect school attendance and attainment (Brackertz 2016, Biddle 2014). Housing instability (as measured by frequent housing moves), renting rather than home ownership, and difficulties in housing affordability (as measured by a family's struggle to pay the rent or mortgage), have been found to have negative effects on children’s physical health, learning outcomes and social and emotional wellbeing (Dockery et al. 2013).

While many of the threats to health from poor housing are common across disadvantaged population groups, the history of colonisation and the relationship of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to their land add to the importance of housing conditions as a determinant of health for Indigenous Australians (Bailie & Wayte 2006).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has identified the importance of addressing appropriate and affordable housing with a specific outcome and targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress. The Closing the Gap Outcome 9 is that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people secure appropriate, affordable housing that is aligned with their priorities and needs. There are two targets, within this outcome area:

- Target 9a: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing to 88 per cent.

- Target 9b: By 2031, all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households:

- within discrete Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, receive essential services that meet or exceed the relevant jurisdictional standard.

- in or near to a town, receive essential services that meet or exceed the same standard as applies generally within the town (including if the household might be classified for other purposes as a part of a discrete settlement such as a ‘town camp’ or ‘town based reserve’).

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

Data findings

Housing tenure

Housing tenure describes whether a household rents or owns their dwelling, or occupies it under another arrangement (ABS 2022b). An Indigenous household is defined as an occupied private dwelling where at least one of the usual residents identifies as being of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander origin. ‘Other households’ are defined as occupied private dwelling without any usual residents who identified as being Indigenous.

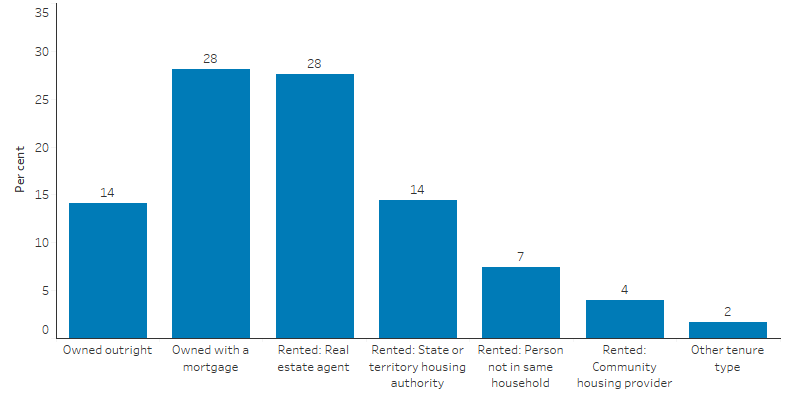

According to data from the ABS Census of Population and Housing, in 2021, 28% (96,600) Indigenous households owned their home with a mortgage, 14% (48,500) owned their home outright, 56% were renting (192,700), and other tenure accounted for the remaining 1.6% (Table D2.01.15).

Looking at types of renters, 35% of Indigenous households were renting privately in 2021 (about 75,000 households) – consisting of people renting their home through a real estate agent (94,800 or 28% of households), or someone else outside their household (25,500 or 7.4%). A further 14% of Indigenous households (49,500) were renting with a state or territory housing authority, 4.0% (13,700) were renting with a community housing provider, and 2.7% had another type of landlord or did not state their landlord type (Table D2.01.15, Figure 2.01.1).

The proportion of Indigenous households who owned their home increased slightly over the last 3 Censuses - from 37% in 2011, to 40% in 2016, and 42% in 2021. The proportion who were renting decreased from 61% in 2011, to 59% in 2016, and 56% in 2021 (Table D2.01.20).

The proportion of households that owned their own home (with or without a mortgage) in 2021 was lower for Indigenous households than for other households (42% compared with 68%) (Table D2.01.15). However, the gap in the home ownership rate between Indigenous and other households narrowed between 2011 and 2021, from 32 to 26 percentage points (Table D2.01.20).

Figure 2.01.1: Tenure type of Indigenous households, Australia, 2021

Source: Table D2.01.15. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2021 (ABS 2022a).

In the Census, the tenure type information is collected for each dwelling, rather than for each person. However, tenure type among different age groups can be estimated using the age of the Census household reference person.

Home ownership among Indigenous households increased with the age group of the reference person, from 4,700 (17%) for households with a reference person aged 18–24, to 52,100 (57%) for those with a reference person aged 55 and over. Conversely, Indigenous households renting with a real estate agent was highest for those with a reference person aged 18–24 (14,400 or 52%) and lowest for those with a reference person aged 55 and over (11,900 or 13%) (Table D2.01.16).

Indigenous households renting with a state or territory housing authority increased with the age group of the reference person, from 3,100 (11%) for those with a reference person aged 18–24, to 15,500 (17%) for those with a reference person aged 55 and over. The proportion of Indigenous households who rented with a community housing provider was lowest for those with a reference person aged 18–24 or 24–34 (both 3.4%), and highest for those with a reference person aged 55 and over (4.5%) (Table D2.01.16).

Housing tenure for Indigenous households also varied by jurisdiction and remoteness. In 2021, Tasmania had the highest proportion of households with a home that was owned outright (21%) or owned with a mortgage (36%). The Northern Territory had the lowest proportions (6.5% and 17%, respectively) (Table D2.01.17).

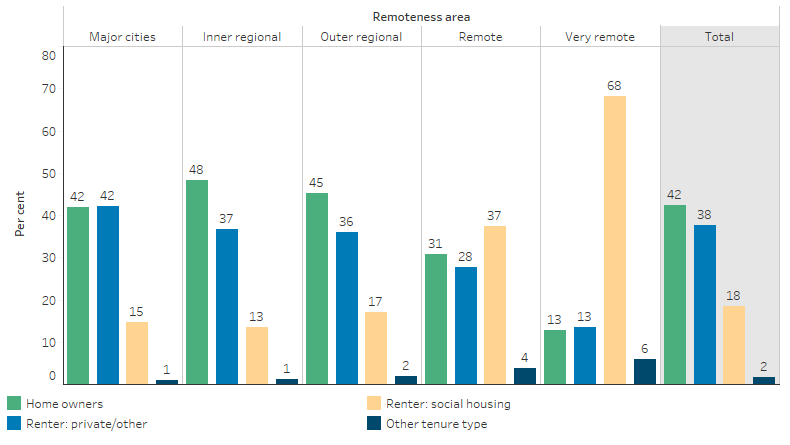

Indigenous households in non-remote areas had higher rates of home ownership (with or without a mortgage) than those in remote areas (44% compared with 21%) (Table 2.01.18). Across 5 remoteness areas, Indigenous households in Inner regional areas had the highest proportion of home ownership (48%): including 17% owned outright and 32% owned with a mortgage. This was followed by Indigenous households in Outer regional areas (45% total home ownership) (Table D2.01.18, Figure 2.01.2).

Indigenous households in Very remote areas had the highest rate of renting (82%). In Very remote areas, 68% of Indigenous households were renting from a social housing provider (48% from a state or territory housing authority, and 20% from a community housing provider) (Table D2.01.18, Figure 2.01.2).

One factor influencing home ownership by remoteness is that in many Remote and Very remote areas much of the land is held communally rather than by individuals through various Indigenous land rights legislation and the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (Australian National Audit Office 2010). Communal-title lands are those in remote Indigenous settlements that are jointly held in some form of a trust for the broader ‘community’ (Memmott 2009). Note that this also affects comparisons by state and territory, reflecting different remoteness distributions.

While a less common occurrence, certain communal-title lands lie within the boundaries of several regional towns and metropolitan cities in Australia; in some cases, these consist of conglomerates of freehold title blocks held collectively through a community housing organisation (Memmott 2009)

Figure 2.01.2: Tenure type of Indigenous households, by remoteness, 2021

Notes

1. 'Renters: Private/other' includes renting from a real estate agent, a person not in same household, other landlord type and landlord type not stated.

2. 'Renters: social housing' includes renting from a state or territory housing authority or a community housing provider.

Source: Table D2.01.18. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2021 (ABS 2023a).

Household composition and tenure type

The 2021 Census showed that there were 352,000 Indigenous households in 2021, of which around:

- 260,400 were one family households (74%) – consisting of 104,435 (30% of all households) couple families with children, 62,751 (18%) couple families without children, 86,135 (24%) one parent families, and 7,040 (2.0%) other one family households.

- 19,000 (5.1%) were multiple family households.

- 54,700 (16%) were lone person households.

- 19,000 (5.4%) were group households (AIHW analysis of ABS 2022a).

In 2021, 46% of Indigenous one family households owned their home (with or without a mortgage). However, the rate of home ownership in this group was different depending on the type of one family household. Over half of Indigenous one family households consisted of couple families who owned their home with or without a mortgage (57% of couple families with children, and 58% of couple families without children), compared with one-quarter of one parent family households.

For Indigenous households consisting of multiple families, the home ownership rate was 47%, while for group households it was 25%. Among Indigenous lone person households, the home ownership rate was 29% (AIHW analysis of ABS 2022a & ABS 2022b).

Housing affordability

One measure of housing affordability is to compare housing costs to gross household income. A household is considered to be in housing stress if housing costs such as mortgage repayments or rent are more than 30% of household income, and the household is in the bottom 40% of the equivalised income distribution (income adjusted by household needs). However, there are many reasons that people may spend more than 30% of gross income on housing costs, other than financial stress – for example, people with higher incomes may choose to spend more than this on housing.

Based on data from the ABS 2021 Census of Population and Housing, 14% of Indigenous households who owned their home with a mortgage were spending more than 30% of their gross income on mortgage repayments (around 11,800 households), a slightly smaller proportion than among other households (16% or 457,000 households) (Table 2.01.33, Table 2.01-1). Among Indigenous households who were renting, just over 1 in 3 (35%) were spending more than 30% of their gross income on rent payments (about 58,900 households), the same proportion to that of other households (35% or 856,500 households).

The proportion of Indigenous households who owned their home with a mortgage and were spending more than 30% of their gross income on mortgage repayments was lower in more remote areas – ranging from 15% in Major cities to 12% in Very remote areas. A larger difference by remoteness was observed for renters. Among Indigenous households who were renting, the proportion spending more than 30% of their gross income on housing costs was 38% in both Major cities and Inner regional areas, compared with 32% in Outer regional areas, 24% in Remote areas, and 13% in Very remote areas (Table D2.01.33). Note that in many Remote and Very remote areas much of the land is held communally rather than by individuals (Australian National Audit Office 2010), which may influence geographic variation in housing affordability.

Table 2.01-1: Mortgage and rent repayments as a proportion of household income by jurisdiction, Indigenous households, 2021

|

Mortgage repayments more than 30% of household income

Number |

Mortgage repayments more than 30% of household income

% of all households |

Rent repayments more than 30% of household income

Number |

Rent repayments more than 30% of household income

% of all households |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NSW |

4,848 |

15.2 |

23,944 |

40.3 |

|

Vic |

1,282 |

14.7 |

5,271 |

33.9 |

|

Qld |

2,868 |

13.0 |

17,008 |

32.6 |

|

WA |

1,263 |

16.3 |

5,092 |

31.6 |

|

SA |

587 |

12.9 |

3,289 |

34.1 |

|

Tas |

510 |

11.0 |

2,130 |

38.2 |

|

ACT |

129 |

9.4 |

540 |

23.6 |

|

NT |

274 |

13.4 |

1,586 |

18.3 |

|

Australia |

11,765 |

14.2 |

58,867 |

34.7 |

Notes

1. Data on mortgage repayments relates to occupied private dwellings owned with a mortgage or being purchased under a shared equity scheme. Excludes households where housing costs as a proportion of income could not be determined.

2. Data on rent payments relates occupied private dwellings being rented. Excludes households where rental payments as a proportion of household income could not be determined.

Source: Table 2.01.33. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2021 (ABS 2022a).

Appropriately sized housing

The 2021 Census of Population and Housing provides information on the number of Indigenous people that are living in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing, as well as the number of households living in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing. Data for both are presented in this section, but note that Target 9a of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap is monitored using data that counts people.

In 2021, 81.4% Indigenous Australians lived in appropriately sized housing (569,400 people). This was an increase from 74.6% in 2011 (Table D2.01.12).

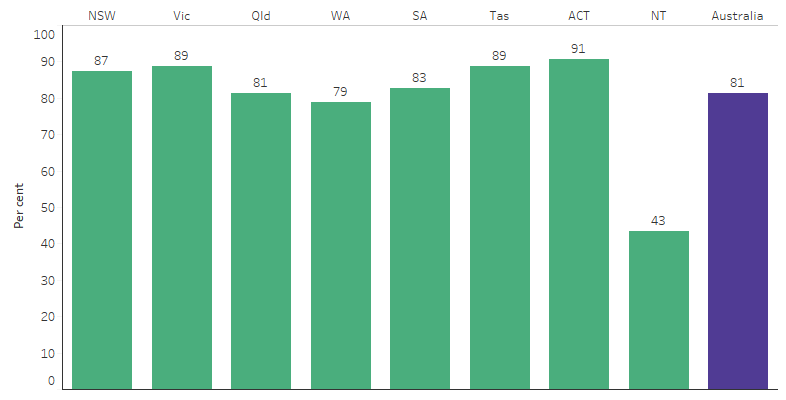

Across states and territories, the proportion of Indigenous Australians who lived in appropriately sized housing ranged from 43% to 91% (Table D2.01.9, Figure 2.01.4).

The proportion of Indigenous Australians living in appropriately sized housing was lower than for non-Indigenous Australians nationally (81% compared with 94%, respectively) (Table D2.01.9). Indigenous Australians were 2.9 times as likely to live in an overcrowded dwelling as non-Indigenous Australians nationally, with the rate across jurisdictions ranging between 1.5 times as high (in New South Wales), to 6.1 times as high (in the Northern Territory) (Table D2.01.9).

Figure 2.01.3: Proportion of Indigenous Australians living in appropriately sized housing (not overcrowded), by jurisdiction, 2021

Source: Table D2.01.9. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2021 (ABS 2022a).

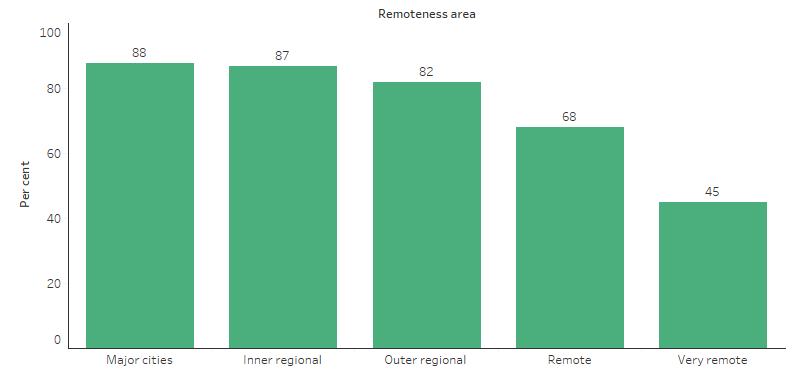

Indigenous Australians in remote areas had higher rates of household overcrowding than those in non-remote areas. In 2021, the proportion of Indigenous Australians living in appropriately sized housing ranged from 88% in Major cities to 45% in Very remote areas (Figure 2.01.4). For non-Indigenous Australians, the proportion living in adequately sized housing ranged from 93% to 95% across remoteness areas (Productivity Commission 2023).

Figure 2.01.4: Proportion of Indigenous Australians living in appropriately sized (not overcrowded) housing, by remoteness area, 2021

Source: Table D2.01.10. Productivity Commission analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing 2021 (Productivity Commission 2023).

Looking at data for households, in 2021, 90.5% (297,700) of Indigenous households were appropriately sized (not overcrowded), compared with 97% of other households (Table D2.01.10). The proportion of Indigenous households that were appropriately sized increased from 87.1% to 90.5% between 2011 and 2021 (ABS 2022b).

The proportion of Indigenous households that were appropriately sized ranged from 93% in Major cities to 69% in Very remote areas (Table D2.01.10, Figure 2.01.3).

Severe overcrowding refers to dwellings that require 4 or more additional bedrooms to accommodate the people who usually live there and is considered a form of homelessness (see also Homelessness). The proportion of Indigenous households that were severely overcrowded was highest Very remote areas, at 5.6% (933 of 16,800 households), followed by Remote areas (1.5%, 202 of 13,800 households). In non-remote areas, 0.1% of Indigenous households were severely overcrowded (433 of 298,500 households) (Table 2.01.10).

For other households, the proportion living in appropriately sized housing was more consistent across remoteness areas, ranging from 96% to 98% across the 5 areas (Table D2.01.10). The proportion of other households that were severely overcrowded was 0.06% or less across all remoteness areas (Table 2.01.10).

Housing assistance

The Australian and state and territory governments provide a range of assistance to people having difficulty with finding or sustaining affordable and appropriate housing in the private housing market. Housing assistance refers to both access to social housing (such as public housing) as well as targeted financial assistance for eligible Australians.

Social housing

Social housing dwellings data are provided by state and territory housing authorities. At 30 June 2022, there were around 442,737 social housing dwellings in Australia (AIHW 2023b).

Data on Indigenous status of the household is collected for public housing, community housing and stated owned and managed Indigenous housing (SOMIH). For Indigenous community housing, this information is unavailable. Throughout this measure, all households living in Indigenous community housing have been assumed to be Indigenous.

At 30 June 2022, there were around 79,166 Indigenous households living in one of the 4 main types of social housing:

- 38,251 in public housing

- 13,424 in SOMIH

- 11,210 in community housing

- 16,281 in Indigenous community housing (AIHW 2023b).

At 30 June 2022, nearly one in five (19%) Indigenous households in public housing had been in the same tenure for a decade or more. In SOMIH, 32% of Indigenous households had been in the same tenure for more than a decade, and 14% for those in community housing (AIHW 2023b). Information on tenure is unavailable for Indigenous Community Housing.

Financial assistance

Commonwealth Rent Assistance (CRA) is the most common form of housing assistance received by Australian households. CRA is a payment provided to eligible families and individuals who pay, or are liable to pay, private rent or community housing rent. CRA is paid at 75 cents for every dollar above a minimum rental threshold until a maximum rate is reached. The minimum threshold and maximum rates vary according to the household or family situation, including the number of children (DSS 2019).

CRA recipients are classified as ‘income units’, rather than households. An income unit can be an individual, or a group of related persons within a household, whose command over income is shared, or any person living in a non-private dwelling who is in receipt of personal income. There can be more than one income unit per household. For this section, the term CRA recipients is used instead of income units.

At 30 June 2022, 89,485 CRA recipients reported having an Indigenous member (6.6% of all recipients).

CRA helps to reduce rental stress (with rental stress defined as spending more than 30% of gross income on rent). In 2022, without CRA, 60,170 recipients with an Indigenous member would have been in rental stress (68% of Indigenous CRA recipients). However, 32,100 Indigenous CRA recipients were still in rental stress after receiving CRA (37%).

Between 2013 and 2022, the proportion of CRA recipients with an Indigenous member who were in rental stress after receiving CRA payments increased from 30% in 2013 to 33% in 2019, then fell substantially to 19% during 2020, before increasing to 37% in 2021 and 2022. It is important to note that in 2020 the calculation of rental stress included the temporary Coronavirus Supplement (AIHW 2023b).

Homelessness

Estimates from the 2021 ABS Census indicate that around 24,900 Indigenous Australians were homeless on Census night (3.1% of the Indigenous population) (ABS 2023b).

The ABS distinguishes between six broad groups of homeless people according to the living situation of the person at the time (see Figure 2.01.5).

Of Indigenous Australians experiencing homelessness at the time of the 2021 Census, about:

- 15,000 (60% of all homeless Indigenous Australians) were living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings (dwellings needing 4 or more extra bedrooms under CNOS).

- 4,800 (19%) were in supported accommodation for the homeless.

- 2,300 (9%) were living in improvised dwellings, tents, or sleeping out (Figure 2.01.5, ABS 2023b).

Figure 2.01.5: Indigenous Australians experiencing homelessness, by living situation, 2021

Source: ABS 2023b: Table 7.3.

Across states and territories:

- Among Indigenous Australians experiencing homelessness in the Northern Territory, Queensland and Western Australia, people living in ‘severely’ crowded dwellings were the largest group, accounting for 85%, 52% and 46% of the homeless Indigenous population in each jurisdiction, respectively.

- People living in supported accommodation for the homeless accounted for the largest group of homeless Indigenous Australians in four jurisdictions – the Australian Capital Territory (where 71% of Indigenous homeless Australians lived in supported accommodation), Victoria (56%), South Australia (47%) and New South Wales (33%).

- In Tasmania, people staying temporarily with other households accounted for the largest proportion of the Indigenous homeless population in this jurisdiction (33%), followed by those in supported accommodation for the homeless (28%) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023b).

Between 2011 and 2021, the number of Indigenous Australians who were homeless decreased from around 26,700 to 24,900. Using population rates, which account for population growth, the rate of homelessness among the Indigenous population declined from 487 to 307 homeless Indigenous Australians per 10,000 population. This was driven by a decline in the number of Indigenous Australians living in severely overcrowded dwellings, which decreased from around 20,100 in 2011 to 15,000 in 2021 (ABS 2023b).

In 2021, Indigenous Australians accounted for 23% of the national homeless population (excluding people for whom Indigenous status was not stated). The rate of homelessness among Indigenous Australians was 8.8 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (307 compared with 35 per 10,000 population) (ABS 2023). The gap in homelessness rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians decreased between 2011 and 2021 (from 453 to 272 per 10,000 population) (AIHW analysis of ABS 2023b).

Use of specialist homelessness services

Specialist homelessness agencies provide a wide range of services to assist people who are experiencing homelessness or who are at risk of homelessness, ranging from general support and assistance to immediate crisis accommodation (AIHW 2022a). Over 314,100 Indigenous clients have been supported by homelessness agencies since the Specialist Homelessness Services Collection (SHSC) began in July 2011.

In 2021–22, around 72,900 Indigenous clients received support from specialist homelessness services (SHS). Of these, over 45,000 (62%) were female and 14,800 (20%) were children aged 0–9.

In 2021–22:

- There were 821 Indigenous SHS clients per 100,000 population nationally. That is, around 8% of the Indigenous population used specialist homeless services.

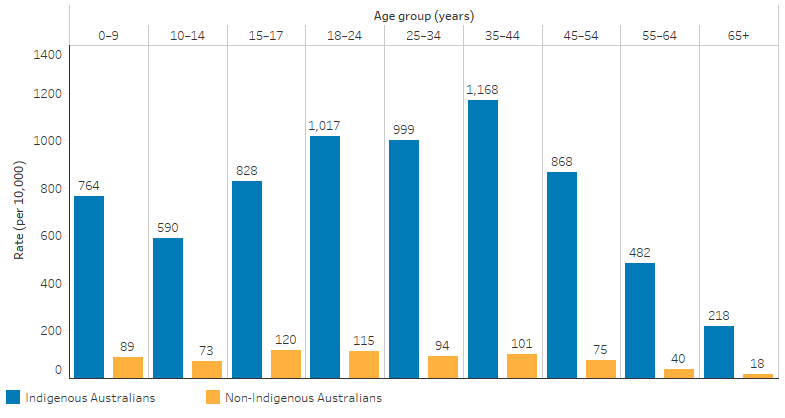

- Indigenous Australians aged 35–44 had the highest rate of specialist homelessness services use (1,168 clients per 10,000 population), followed by those aged 18–24 (1,017 clients per 10,000) and 25–34 (999 per 10,000).

- Indigenous Australians used specialist homelessness services at 11 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (821 compared with 74 per 10,000 population). Across age groups, the rate for Indigenous Australians ranged between 6.9 and 12.4 times higher than for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D2.01.21 and Figure 2.01.6).

Figure 2.01.6: Specialist homelessness services clients, by Indigenous status and age, 2021–22

Source: Table D2.01.21. AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2021–22.

In 2021–22, New South Wales had the largest number of Indigenous Australians receiving support from specialist homelessness services with 21,400 Indigenous clients, followed by 15,100 in Queensland. Rates ranged from 1,689 per 10,000 population in Victoria to 356 per 10,000 in Tasmania (Table D2.01.30 and Figure 2.01.7).

Figure 2.01.7: Specialist homelessness services clients, Indigenous Australians, by jurisdiction, 2021–22

Source: Table D2.01.30. AIHW Specialist Homelessness Services Collection 2021–22.

In 2021–22, more than half of Indigenous clients (58%, or almost 42,300 clients) presented to homelessness services alone, and a further 32% (or almost 23,500 clients) presented as a single person with children (Table D2.01.22).

The 3 most common reasons why Indigenous clients sought assistance from SHS agencies in 2021–22 were:

- family and domestic violence (24% or almost 17,100 clients),

- housing crisis (19% or around 13,700 clients), and

- inadequate or inappropriate dwelling conditions (13% or almost 9,300 clients) (Table D2.01.31).

Of Indigenous clients who were homeless at the beginning of their first support period:

- 39% had been living in short-term temporary accommodation,

- 30% had been ‘couch surfing’, and

- 12% had been living without shelter (Table D2.01.32).

Housing situation outcomes for SHS clients

In 2021–22, for Indigenous clients with closed support, the proportion experiencing homelessness decreased from 45% at the start of support to 37% at the end. More Indigenous clients were also living in housing with some form of tenure at the end of the support period, mainly an increase in clients living in public or community housing (from 31% to 38%) (AIHW 2022a). Note: This information is limited only to clients who have stopped receiving support during the financial year, and who were no longer receiving ongoing support from a SHS agency,

In 2021–22, 79% (14,700) of Indigenous SHS clients who were at risk of homelessness within the first six months of the financial year were assisted to avoid homelessness over the following 6 months– a 3.2 percentage point increase since 2018–19.

Among Indigenous SHS clients who had at least one support period with a monthly housing status of ‘homeless’ during in 2021–22, 11,000 (28%) were experiencing persistent homelessness – that is, they had been homeless for more than 7 months over a 24-month study period (AIHW 2022a). This was an increase from around 8,000 Indigenous clients experiencing persistent homelessness since 2018–19.

SHS use over time –a cohort analysis

Using the specialist homelessness services longitudinal data set, analysis of a cohort of adult Indigenous clients in 2015–16 was undertaken to examine SHS support patterns for this cohort of service users (AIHW 2022b). The Indigenous 2015–16 cohort was defined as clients who received a service in 2015–16 and longitudinal analyses was performed over the period 2011–12 to 2020–21. There were 38,600 clients in the adult Indigenous 2015–16 cohort, and these clients had the following key characteristics:

- Less than 20% were aged 45 or over.

- Nearly half (19,000 clients) had only one support period during the defining study period and 28% (10,800) had 3 or more support periods.

- Half (19,400 clients) were experiencing housing crisis (a reason for seeking assistance) and 44% (17,200) were experiencing financial difficulties.

- Over half (56%) had received SHS support previously; that is, 21,600 clients received SHS support in the 48-month retrospective period that preceded the defining study period.

- Over 23,000 clients (60%) continued to receive support into the future; that is, they received support in the 48 months after the 12-month defining study period.

- One in five (20% or 7,700) Indigenous cohort clients received short-term accommodation in the defining period and needed short-term accommodation again in the prospective period.

Indigenous clients were also more likely to have presented with children and need short-term or emergency accommodation than non-Indigenous clients. They were also more likely to have experienced homelessness and to be long-term clients. Client traits or experiences, as reported during the defining study period, associated with either a history of or future SHS support include having transitioned from custody, experiencing family and domestic violence or problematic drug/alcohol issues (AIHW 2022b).

Research and evaluation findings

The research explores several areas related to housing and its intersection with health and wellbeing. These are explored in further detail below:

- Overcrowding—Overcrowding and the associated health implications can emerge from an insufficient supply of housing, inappropriate housing and community design, and poor housing conditions (Clifford et al. 2015). Overcrowded housing conditions can lead to poor hygiene and the spread of infectious diseases such as respiratory illnesses, and the infections that can lead to Acute Rheumatic Fever (Clifford et al. 2015; AIHW 2023a) and subsequently Rheumatic Heart Disease as well as acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis (Marshall et al. 2011 ; Cannon & Bowen 2021).Overcrowding puts additional pressure on facilities and infrastructure thereby limiting the ability of residents to employ healthy living practices (Bailie & Wayte 2006) (see measure 2.02 Access to functional housing with utilities). Further, multiple studies have shown overcrowded housing results in an increased number of COVID-19 infections and a higher mortality rate (Aldridge R et al. 2021; Varshney et al. 2022).

- Homelessness—Homelessness is directly linked to experiences of domestic violence, alcohol and drug problems, financial hardship and unmet need for public housing (Graham et al. 2014; Memmott et al. 2012). There are also strong interrelationships between homelessness and mental health. While a mental health episode can trigger homelessness, the isolation and trauma of homelessness (in particular that associated with rough sleeping) can also precipitate mental illness (Brackertz et al. 2018).

- Home ownership—Home ownership can provide various indirect health and socioeconomic benefits beyond simple security of tenure. For example, Fichera and Gathergood (Fichera & Gathergood 2016) found strong evidence that increases in wealth from rising house prices reduce non-chronic health conditions and improve self-assessed health. Their analysis suggests that increased wealth does not improve physical health through improved mental health, but through individuals being able to reduce their intensity of work.

- Affordability—Affordability of housing is an issue across different types of tenure in Australia. A lack of housing affordability can create stress, which affects a person’s sense of stability and control in their lives (Foster et al. 2011).

Findings from the House of Representatives Standing Committee Inquiry into Homelessness (HRSC 2021) recommended a review of homelessness data collection and estimation methods. The inquiry recommended greater inclusion of Indigenous Australian cultural practices and perspectives, particularly regarding the circumstances in which persons living in severely crowded dwellings and boarding houses should be categorised as homeless. The findings also highlight the effectiveness and appropriateness of Aboriginal community-controlled housing services, and recommended the development of a national integrated approach to housing and homelessness services for Indigenous Australians, co-designed with Indigenous community-controlled organisations and grounded in the principle of self-determination.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are a national priority cohort in the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement, which came into effect 1 July 2018 (Council on Federal Financial Relations 2018). This agreement provides a framework for all levels of government to work together to improve housing and homelessness outcomes for Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2019).

It is important to note that Indigenous Australian experiences of homelessness and overcrowding may differ from common statistical measures. For example, homelessness for some Indigenous Australians may include disconnection with one’s homeland or kinship networks, contrary to official statistics that may be based on characteristics of one’s typical living arrangements (ABS 2014; AIHW 2014b). Some Indigenous Australian public space dwellers who choose to ‘live rough’ may not necessarily see themselves as homeless (Memmott et al. 2003).

According to the widely used density model of overcrowding—the CNOS—dwellings requiring at least one additional bedroom are considered overcrowded. In general, this model is a useful tool for assessing overcrowding. However, some studies have questioned whether CNOS is the appropriate method for measuring overcrowding within the Indigenous context due to the Indigenous-specific cultural and behavioural factors (Memmott et al. 2011).

For example, the CNOS does not take into consideration the Indigenous cultural practice of 'demand sharing', which can lead households to be seen as 'crowded' (Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute 2017). Maintaining a large, open household is a core element for many Indigenous Australians, driven by a culture of sharing and connection to family. Household size can vary due to visiting family seeking temporary or semi-permanent accommodation for reasons such as accessing health or other services in the area, or attending cultural events.

The Remote Housing Review in 2017 (PM&C 2017) noted that while significant progress in reducing overcrowding has been made, a range of ongoing issues still needed to be addressed. For example, the Review estimated, after accounting for population growth, an additional 5,500 homes are required by 2028 to reduce levels of overcrowding in Remote areas to more acceptable levels. Half of the additional need is in the Northern Territory alone.

An evaluation of the Housing for Health Program found that those who received the Housing for Health intervention had a significantly reduced rate of hospitalisations for infectious diseases—40% less than the hospitalisation rate for the rest of the rural New South Wales Aboriginal population without the Housing for Health interventions (NSW Department of Health 2010, 2019).

Bailie and colleagues (Bailie et al. 2011) supported existing Australian and international literature in their claim that housing programs that are focused on improving the functional state of the infrastructure have a limited effect on housing-related health risks, such as domestic hygiene, at the community level. For example, levels of overcrowding may remain high despite improvements to physical infrastructure, enabling poor domestic hygiene to persist. The authors propose hygiene promotion programs as important complementary initiatives to infrastructure improvement projects.

Implications

While there have been improvements in overcrowding, home ownership and a reduction in homelessness, the disparities across remote areas remain. There is a continued need for public policy that aims to ensure access to affordable, safe and sustainable housing for Indigenous Australians, particularly in the most affected areas.

Remote housing programs have delivered improvements, but the persistent high rate of overcrowding in remote areas show there are still advances to be made. Involving communities in the design, construction and maintenance of housing can build capacity for improved housing-related health outcomes (Ware 2013). Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement: Building the Community Controlled Sector - targets four key policy areas, including housing. Priority Reform Two recognises that building strong community-controlled sectors requires national effort and joined up delivery against all sector elements.

In line with Priority Reform Two, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Housing Association (NATSIHA) led work on a Housing Sector Strengthening Plan (the Housing SSP) with the Department of Social Services, along with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled organisations and representatives from jurisdictions. The Housing SSP outlined 14 priority actions over the next three years to transform and grow the sector. These actions are the result of targeted consultation with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Controlled Housing Organisations across Australia.

Another key mechanism for working with Indigenous organisations and community is the Housing Policy Partnership (HPP). This is an agreement between the Australian, state and territory governments, the Coalition of Peaks (CoP) and independent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives, including NATSIHA to develop joined up approaches to Indigenous housing policy. Home ownership, particularly when in established housing markets, can lead to greater economic opportunities and create wealth for Indigenous Australians. However, there are also unique challenges in purchasing a home on Indigenous land, which all jurisdictions have a role in addressing (Select Council on Housing and Homelessness 2013).

Mainstream public housing and community housing services offered in non-remote areas should be flexible in supporting Indigenous tenants to achieve and maintain tenancies. This can be done by recognising that cultural values, kinship obligations and practices can affect the ability of tenants to comply with tenancy requirements. Inflexible and coercive tenancy requirements that lack formal incentives could disadvantage Indigenous Australian tenants. More flexible approaches could be effective, such as having culturally competent housing staff empowered to work locally with Indigenous tenants in constructive ways (Memmott et al. 2016). Flexible approaches could reduce the risk of evictions and entry into homelessness. The Wongee Mia project is an example of an innovative approach to working with the extended family’s needs, rather than just the individual to prevent unnecessary eviction, including providing case-worker support and housing for other family members (Vallesi et al. 2020).

The proportion of Indigenous clients of Specialist Homeless Services at risk of homelessness that have been assisted to avoid homelessness has increased. As these clients often have characteristics that make them particularly vulnerable, such as having experienced domestic violence, mental health issues, drug and alcohol issues, and transitioning from custody, it is important that housing, health and other services collaborate so that housing instability does not exacerbate these issues further. Not only should these services collaborate, but they should also be culturally appropriate.

A number of programs in Australia have been implementing a ‘Housing First’ approach that prioritises safe and permanent housing as a foundation for assisting an individual’s other health and social needs. This contrasts with the alternative approach that assists people to be ‘housing ready’ by addressing those other needs first. An international study of homeless people with disabilities found that ‘Housing First’ programs are more effective than programs that require clients to be ‘housing ready’ in terms of improved housing stability, reduced homelessness, health benefits and reduced health service use (Peng et al. 2020).

This measure has not fully explored Indigenous Australians’ use of social housing services, particularly in non-remote areas, but this may be explored in future editions. Further research is needed to understand changes in patterns of social housing services use and their effects.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2014. Information Paper: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Perspectives on Homelessness 2014 Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2022a. 2021 Census - counting dwellings, place of enumeration [Census TableBuilder].

- ABS 2022b. Housing Statistics for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Canberra: ABS. Viewed April 2023.

- ABS 2023a. 2021 Census - counting dwellings, place of enumeration [Census TableBuilder].

- ABS 2023b. Estimating Homelessness: Census. Canberra.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2014a. Housing circumstances of Indigenous households: tenure and overcrowding. Cat. no. IHW 132. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014b. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2019. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a focus report on housing and homelessness. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Specialist homelessness services annual report 2021–22. Canberra.

- AIHW 2022b. Specialist homelessness services client pathways: Indigenous clients in 2015–16. Canberra.

- AIHW 2023a. Acute rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease in Australia 2017–2021, catalogue number CVD 99. AIHW, Australian Government.

- AIHW 2023b. Housing assistance in Australia. Canberra.

- Aldridge R, Pineo H, Fragaszy E, Eyre M, Kovar J, Nguyen V et al. 2021. Household overcrowding and risk of SARS-CoV-2: analysis of the Virus Watch prospective community cohort study in England and Wales. Wellcome Open Research 6:637.

- Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute 2017. Understanding 'demand sharing' of Indigenous households. Viewed 9 May 2023.

- Australian National Audit Office 2010. Home Ownership on Indigenous Land Program. Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs.

- Bailie RS, McDonald EL, Stevens M, Guthridge S & Brewster DR 2011. Evaluation of an Australian Indigenous housing programme: community level impact on crowding, infrastructure function and hygiene. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 65:432.

- Bailie RS & Wayte KJ 2006. Housing and health in Indigenous communities: key issues for housing and health improvement in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Australian Journal of Rural Health 14:178-83.

- Biddle N 2014. Developing a behavioural model of school attendance: Policy implications for Indigenous children and youth. Canberra.

- Brackertz N 2016. Indigenous Housing and Education Inquiry: Discussion Paper for Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Melbourne: AHURI Research Service.

- Brackertz N & Wilkinson A 2017. Research synthesis of social and economic outcomes of good housing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People.

- Brackertz N, Wilkinson A & Davison J 2018. Housing, homelessness and mental health: towards systems change. AHURI Research Paper, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

- Cannon JW & Bowen AC 2021. An update on the burden of group A streptococcal diseases in Australia and vaccine development. Med J Aust 215:27-8.

- Clifford H, Pearson G, Franklin P, Walker R & Zosky G 2015. Environmental health challenges in remote Aboriginal Australian communities: clean air, clean water and safe housing. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin 15:1-13.

- Council on Federal Financial Relations 2018. homeless’ during in 2021–22.

- Dockery AM, Ong R, Colquhoun S, Li J & Kendall G 2013. Housing and children’s development and wellbeing: evidence from Australian data. Melbourne: AHURI.

- DSS (Department of Social Services) 2019. Housing support–Commonwealth Rent Assistance- external site opens in new window. Department of Social Services. Viewed 8 May 2023.

- Fichera E & Gathergood J 2016. Do wealth shocks affect health? New evidence from the housing boom. Health economics 25:57-69.

- Foster G, Gronda H, Mallett S & Bentley R 2011. Precarious housing and health: research synthesis.

- Graham D, Wallace V, Selway D, Howe E & Kelly T 2014. Why are so many Indigenous Women Homeless in Far North and North West Queensland, Australia? Service Providers’ Views of Causes. Journal of Tropical Psychology Volume 4.

- HRSC (House of Representatives, Standing Committee) 2021. Inquiry into homelessness in Australia: Final report. Canberra: House of Representatives Standing Committee on Social Policy and Legal Affairs.

- Marsh A, Gordon D, Heslop P & Pantazis C 2000. Housing deprivation and health: A longitudinal analysis. Hous. Stud. 15:411-28.

- Marshall CS, Cheng AC, Markey PG, Towers RJ, Richardson LJ, Fagan PK et al. 2011. Acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis in the Northern Territory of Australia: a review of 16 years data and comparison with the literature. Am J Trop Med Hyg 85:703-10.

- Memmott P 2009. Indigenous home ownership on communal title lands. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute.

- Memmott P, Birdsall-Jones C, Go-Sam C, Greenop K & Corunna V 2011. Modelling crowding in Aboriginal Australia. AHURI positioning paper no. 141. . Melbourne: AHURI.

- Memmott P, Birdsall-Jones C & Greenop K 2012. Australian Indigenous house crowding. Melbourne: AHURI.

- Memmott P, Long S, Chambers C & Spring F 2003. Categories of Indigenous' homeless' people and good practice responses to their needs. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Queensland Research Centre.

- Memmott P, Moran M, Nash D, Fantin S & Birdsall-Jones C 2016. Understanding how policy and tenancy management conditionality can influence positive housing outcomes for Indigenous Australians. AHURI Research and Policy Bulletin No. 209.

- NSW Department of Health 2010. Closing the Gap: 10 Years of Housing for Health in NSW - An evaluation of a healthy housing intervention. (ed., Department of Health - NSW). Sydney: DoH-NSW.

- NSW Department of Health 2019. Housing for Health. Viewed 20/08/2019.

- Peng Y, Hahn RA, Finnie RKC, Cobb J, Williams SP, Fielding JE et al. 2020. Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First to Reduce Homelessness and Promote Health Among Homeless Populations With Disability: A Community Guide Systematic Review. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 26:404-11.

- PM&C (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) 2017. Remote Housing Review: A review of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing and the Remote Housing Strategy (2008-2018). (ed., Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet). Canberra.

- Productivity Commission 2023. Closing the Gap Information Repository.

- Select Council on Housing and Homelessness 2013. Select Council on Housing and Homelessness, 2013, Indigenous Home Ownership Paper. (ed., Department of Families H, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs). Canberra: 2013.

- Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E & Petticrew M 2013. Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews:CD008657.

- Vallesi S, Tighe E, Bropho H, Potangaroa M & Watkins L 2020. Wongee Mia: An Innovative Family-Centred Approach to Addressing Aboriginal Housing Needs and Preventing Eviction in Australia. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17.

- Varshney K, Glodjo T & Adalbert J 2022. Overcrowded housing increases risk for COVID-19 mortality: an ecological study. BMC Research Notes 15:126.

- Ware VA 2013. Housing strategies that improve Indigenous health outcomes. Canberra: AIHW produced for Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.