Key facts

In 2018–19:

Why is it important?

Self-assessed health status provides a measure of the overall level of a population’s health based on peoples’ personal perceptions of their own health. Health status is sometimes used to analyse differentials within and between populations, to monitor trends over time and to assess changes in response to health policy and practice (Cunningham et al. 1994). Health is recognised as having physical, mental, social and spiritual components. Therefore, the measurement of health must go beyond quantifying levels of morbidity and mortality. Part of this broader approach is to ask people to assess the state of their own health.

Self-assessed health status is a subjective measure dependent on an individual’s awareness and expectations regarding their health and their comparisons with others around them. It is influenced by various factors, including access to health services and information, the extent to which health conditions have been diagnosed, health literacy and level of education (AIHW 2018; Delpierre et al. 2009). Global self-ratings are widely used in general health research, drawing on the multitude of physical, environmental, social and mental domains that encompass disease and wellbeing (Chand et al. 2017). Social constructs of health also influence this assessment, such as culturally distinct views of health and wellbeing held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, the existing level of health within a community and judgments concerning the person’s own health compared with others in their community (OECD 2017; Vass et al. 2011).

Internationally, self-assessed health status correlates with measures of health, such as reported long-term health conditions, recent health-related actions, and the presence of disability. However, many Indigenous Australians rate their health as good or excellent despite significant health problems. This may reflect the social and cultural constructs of health mentioned above. This is why a greater understanding of the cultural determinants of health and potential protective factors is needed.

Self-assessed health status is a proxy measure of overall health status, but is not an objective measure and needs to be interpreted with caution. Despite this concern, survey data of self-assessed health status is used as a tool for cross-tabulation with other issues captured in the same survey particularly social determinants and risk factors. This can be useful for investigating associations between characteristics, such as demonstrating a social gradient.

Data findings

Perceived health by Indigenous status

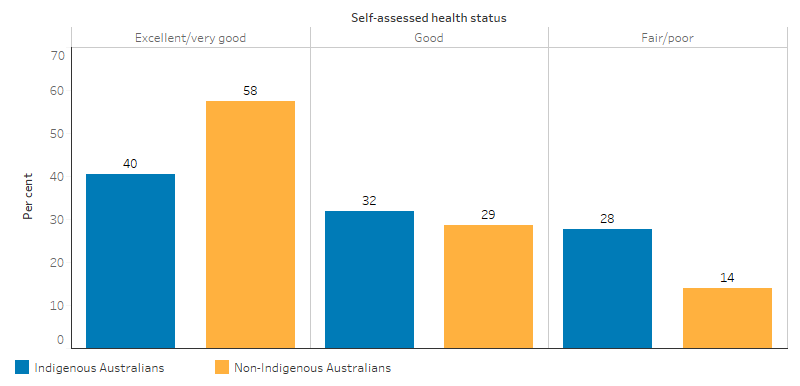

Based on data from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Health Survey), 45% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported their health as being excellent/very good, 32% rated their health as good, and 24% rated their health as being fair/poor. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were less likely to report their health as excellent/very good compared with non-Indigenous Australians (40% compared with 58%, respectively), and twice as likely to rate their health as being fair/poor (28% compared with 14%) (Table D1.17.5, Figure 1.17.1).

Figure 1.17.1: Self-assessed health status (age-standardised), by Indigenous status, persons aged 15 and over, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19; National Health Survey 2017–18.

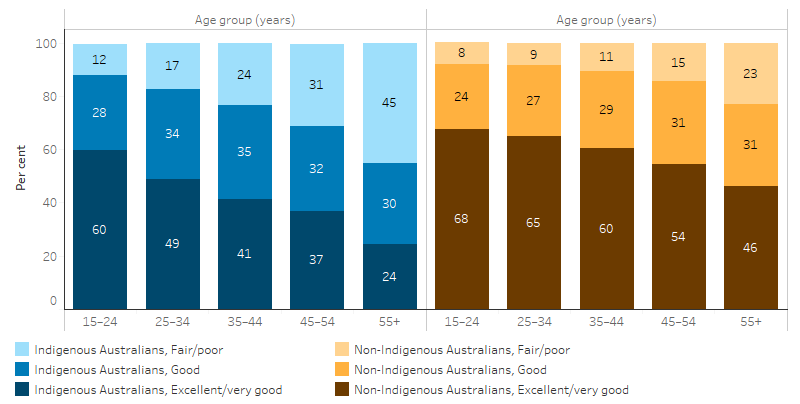

Indigenous males (47%) were more likely than Indigenous females (42%) to report their health as being excellent/very good (Table D1.17.6). Indigenous Australians aged 15–24 were more likely to rate their health as excellent/very good (60%), compared with 24% of those aged 55 and over. Indigenous Australians in all age groups were less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to report excellent/very good health, particularly for those aged 55 and over (a difference of 22%) (Table D1.17.5, Figure 1.17.2). In 2014–15, the majority of Indigenous parents rated the health of their children aged 0–14 as excellent/very good (83%), with only 4% reporting their children’s health as fair/poor (Table D1.17.11).

Figure 1.17.2: Self-assessed health status, by Indigenous status and age group, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19; National Health Survey 2017–18.

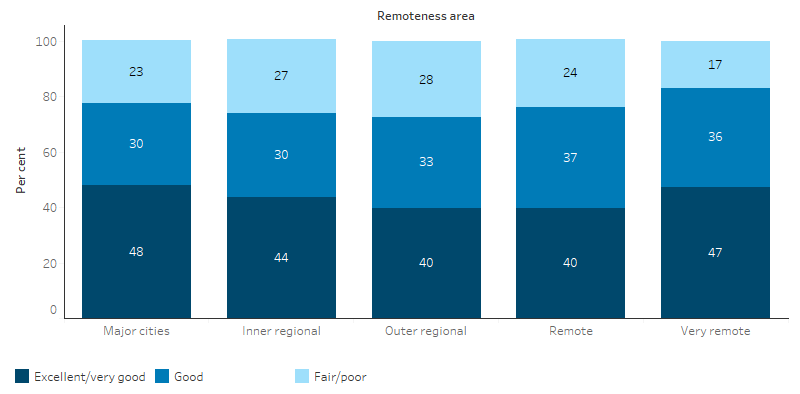

Indigenous Australians living in Remote areas were more likely to have better perceived health status. Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over living in Remote areas were more likely to report their health as being excellent (18%) compared with those living in Non-remote areas (16%) (Table D1.17.10, Figure 1.17.3).

Figure 1.17.3: Self-assessed health status, Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, by remoteness, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.10. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

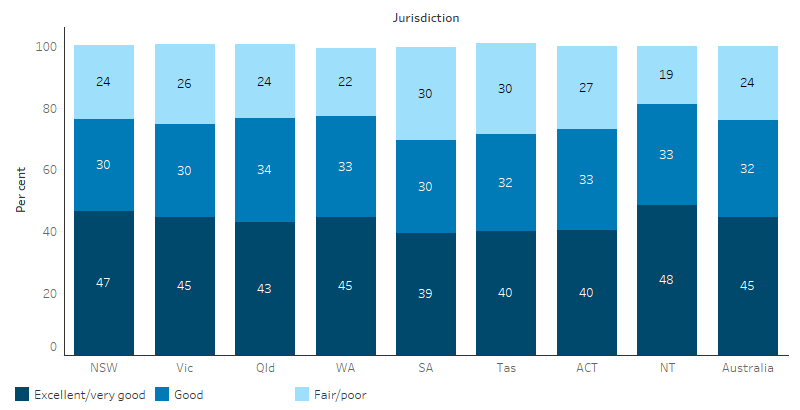

Indigenous Australians living in the Northern Territory were more likely to report their health as excellent/very good (48%), and less likely to report their health as being fair/poor (19%) compared with Indigenous Australians living in any other jurisdiction (Table D1.17.8, Figure 1.17.4).

Figure 1.17.4: Self-assessed health status, Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, by jurisdiction, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.8. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

Changes over time

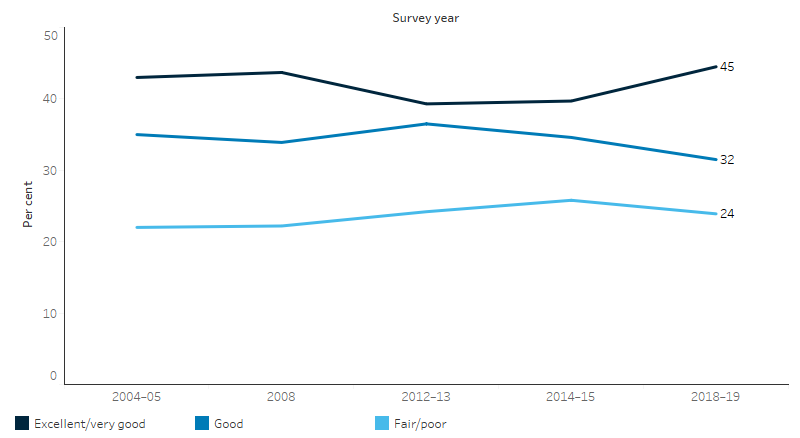

Between 2012–13 and 2018–19, there was an increase in the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who rated their health as excellent/very good (from 39% to 45%), and a decline in the proportion of those who rated their health as good (from 37% to 32%) (Table D1.17.5, Figure 1.17.5).

Figure 1.17.5: Self-assessed health status of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, 2004–05, 2008, 2012–13, 2014–15, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2004–05; National Health Survey 2004–05; National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2008; National Health Survey 2007–08; Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2012–13 (2012–13 Core component); Australian Health Survey 2011–13 (2011–12 Core component); National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15; National Health Survey 2014–15; ABS (unpublished) National Health Survey 2017-18; National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

Factors influencing perceived health status

The findings that a higher proportion of people in Remote and Very remote areas rate their health as excellent warrants further consideration. Despite these results, there is evidence that a number of health conditions such as circulatory diseases (see measure 1.05 Cardiovascular disease) and kidney diseases (see measure 1.10 Kidney disease) and risk factors such as smoking (see measure 2.15 Tobacco use) are worse in Remote areas. Interpretation of the question of health status will be influenced by the person’s view of ‘health’ and whether the concept is perceived holistically to include social, cultural, emotional and spiritual wellbeing or as a biomedical concept linked to the absence of disease and incapacity (NAHSWP 1989; Vass et al. 2011). It can also be influenced by whether health conditions have been diagnosed. Self-assessed health can also be influenced by how an individual assesses their own health relative to other people around them.

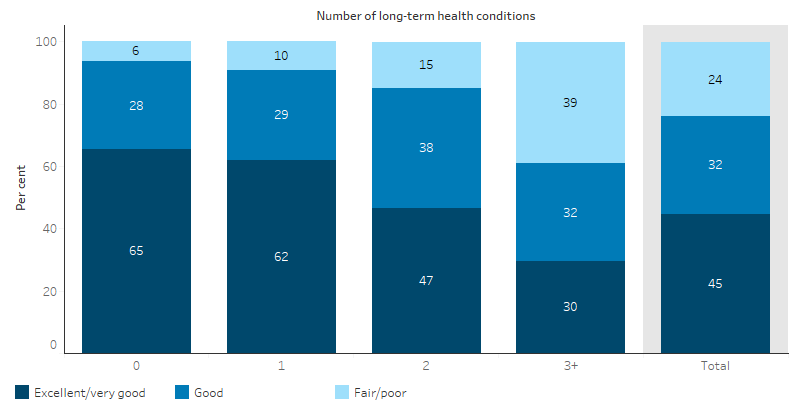

In 2018–19, the proportion of Indigenous Australians reporting fair/poor health increased with the number of long term health conditions reported. Among Indigenous Australians who reported having more than three long-term medical conditions, 39% reported their health as being fair/poor, however, of those who did not report any long-term conditions, 6% reported fair/poor health (Table D1.17.4, Figure 1.17.6). In 2014–15, 53% of Indigenous Australians with no disability or restrictive long-term health condition reported their health as excellent/very good, compared with 23% of those with a disability or restrictive long-term health condition (ABS 2016) (Table 28.3).

Figure 1.17.6: Self-assessed health status of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, by number of long-term health conditions, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.17.4. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

Social determinants and perceived health status

Social determinants are the circumstances in which people grow, live, work and age. They can be measured by indicators that reflect an individual’s personal situation. For Indigenous Australians, social determinants starts with factors such as cultural identity, family, participation in cultural activities and access to traditional lands (ABS 2016), and then moves to include income, education, employment, and levels of social support and social inclusion.

Data shows that these social determinants are related to self-perceived health with those having more personal, economic and social resources rating their own health more positively:

- In 2014–15, excellent/very good self-assessed health status was associated with feeling safe (88%), feeling able to have a say with family or friends (92%) and within the community (53%), having friends and family outside the household to confide in (84%), feeling safe walking alone after dark (59%), no community problems reported (31%), agreeing that most people can be trusted (37%) and having daily contact with family or friends outside the household (24%) (Table D1.17.12) (see measure 1.13 Community functioning).

- In 2018–19, 54% of employed Indigenous Australians reported excellent/very good health, compared with 43% of those not employed. Fifty-four per cent of Indigenous Australians who completed Year 12 reported excellent/very good health, compared with 33% of those who had completed Year 9 or below (Table D1.17.2).

- In 2018–19, 63% of Indigenous Australians living in households in the highest income quintiles (4th and 5th quintiles) reported excellent/very good health, compared with 38% of those in the lowest quintile. Indigenous Australians who did not suffer from financial stress, owned a house, and lived in overcrowded households were more likely to report their health as being excellent/very good (Table D1.17.3) (see measure 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing).

Research and evaluation findings

Studies show that there is a significant gap in the health status of Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Between one-third and one-half of the gap in health status is associated with differences in socioeconomic status. Disparities in access to health services, variations in health behaviour (Booth & Carroll 2005) and racism (Paradies & Cunningham 2012), also contribute. However, there is also a large component that is unexplained.

Studies highlight how the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander understanding of health is holistic and refers to the social, emotional, and cultural wellbeing of the whole community. This understanding of health affects their perceived health status. Studies suggest that health care services should aim to achieve the state where every individual is able to achieve their full potential as human beings, and bring about the total wellbeing of their communities (Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2020; Gee et al. 2014).

This holistic understanding of health and wellbeing involves the whole community throughout the life-course. It includes broad issues like social justice, equity, and rights, as well as traditional knowledge, traditional healing, and connection to country, that all give them meaning (DoHA 2013; Swensen 1995). Thus, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander concept of health “encompass[es] mental health and physical, cultural and spiritual health. Land is central to wellbeing” (Swensen 1995).

The Mayi Kuwayu Study, is a national longitudinal study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing. The research aims to understand how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture links to health and wellbeing. Their connection to country, and enduring cultures and values, are considered critical to health and wellbeing, alongside physical, psychological and social factors. This research is helping address a gap in large-scale survey data that adequately represent the experiences of Indigenous Australians; including evidence on cultural practice and expression. This Study will provide information for community, services and policy makers about things that improve Indigenous Australian’s health and wellbeing. The Mayi Kuwayu Study aims to contribute to filling key evidence gaps, including quantifying the contribution of cultural factors to wellbeing, alongside standard elements of health and risk (Jones et al. 2018; NCEPH RSPH 2020).

Traditional medicine also plays a role in Indigenous Australians health and perceived health status. Traditional medicine practice (TMP) within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures in Australia follows a holistic world view, with the belief that the mind and body are inseparable and that to prevent ill health there is a need to maintain a balance between the physical and spiritual selves (Ralph-Flint 2001). Research shows that for Indigenous Australians the impact of colonisation and the removal and disconnection of people both from their land and from their traditional families, has had a major effect on the use of traditional practices including traditional medicine (Campbell et al. 2011). Present day practitioners and healing centres of bush medicine offer a wealth of knowledge that can be used to improve understanding of the process of healing, interpret symptoms and provide traditional healing treatments (Ralph-Flint 2001).

Implications

Further research is warranted into the contrasts between perceived health status and measured health status, such as in Remote versus Non-remote, male versus female, and Indigenous Australians’ concept of 'good' health versus non-Indigenous Australians’ concept of 'good' health status.

A broader understanding of Indigenous Australian health and wellbeing within a cultural context will help to understand the potential protective factors to wellbeing that culture can provide. There is a lack of large-scale data that adequately represent the experiences of Indigenous Australians; including quantifying the contribution of cultural factors to wellbeing, alongside standard elements of health and risk factors (Jones R et al. 2018).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2016. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15. Cat. no. 4714.0. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2018. Australia’s health 2018. Canberra.

- Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet 2020. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander concept of health. Mt Lawley: Edith Cowan University. Viewed 14/07/2020.

- Booth A & Carroll N 2005. The Health Status of Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Australians. Canberra: CAEPR.

- Campbell D, Burgess CP, Garnett ST & Wakerman J 2011. Potential primary health care savings for chronic disease care associated with Australian Aboriginal involvement in land management. Health Policy 99:83-9.

- Chand R, Parker E & Jamieson L 2017. Differences in, and Frames of Reference of, Indigenous Australians' Self-rated General and Oral Health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 28:1087-103.

- Cunningham J, Sibthorpe B & Anderson I 1994. Australian Bureau Of Statistics National Centre For Epidemiology And Population Health Occasional Paper 4707.0: Self-Assessed Health Status, Indigenous Australians. Age 15:34.9.

- Delpierre C, Lauwers-Cances V, Datta GD, Lang T & Berkman L 2009. Using self-rated health for analysing social inequalities in health: a risk for underestimating the gap between socioeconomic groups? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 63:426-32.

- DoHA (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing) 2013. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan: 2013-2023. Department of Health.

- Gee G, Dudgeon P, Schultz C, Hart A & Kelly K 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander social and emotional wellbeing. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice 2:55-68.

- Jones R, Thurber KA & Chapman J on behalf of the Mayi Kuwayu Study Team 2018. Study protocol: Our Cultures Count, the Mayi Kuwayu Study, a national longitudinal study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing. BMJ Open 8.

- Jones R, Thurber KA, Chapman J, D’Este C, Dunbar T, Wenitong M et al. 2018. Study protocol: our cultures count, the Mayi Kuwayu study, a national longitudinal study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander wellbeing. BMJ open 8.

- NAHSWP (National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party) 1989. A national Aboriginal health strategy. NAHS Working Party.

- NCEPH RSPH (National Centre for Epidemiology and Population Health - Research School of Population Health) 2020. Mayi Kuwayu Study Canberra: The Australian National University. Viewed 14/7/2020.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) 2017. Health at a Glance 2017.

- Paradies YC & Cunningham J 2012. The DRUID study: racism and self-assessed health status in an Indigenous population. BMC Public Health 12:131.

- Ralph-Flint J 2001. Cultural borrowing and sharing: Aboriginal bush medicine in practice. Australian Journal of Holistic Nursing, The 8:43.

- Swensen G, Serafino, S., Thomson, N. 1995. Suicide in Western Australia, 1983-1992. Perth: State Health Purchasing Authority, Health Department of Western Australia.

- Vass A, Mitchell A & Dhurrkay Y 2011. Health literacy and Australian Indigenous peoples: an analysis of the role of language and worldview. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 22:33-7.