Key facts

In 2014–15

Why is it important?

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have long sought improved health outcomes through improvements in the physical, social, cultural and emotional elements of their lives. This includes the ability to live proudly and freely as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2004). ‘Functioning’ refers to people being able to achieve wellbeing which includes, ‘being adequately nourished and being free from avoidable disease, being able to take part in the life of the community and having self-respect’ (AIHW 2014; Sen 1999). Functioning is influenced by the values and attitudes of individuals, families and communities and by the social and cultural environments in which they live. Different cultures give greater or lesser priority to different types of functioning, and do not necessarily align with Western perspectives (Sen 1999; Taylor et al. 2012).

Within the context of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF), ‘Community Functioning’ is defined as the ability and freedom of community members and communities to determine the context of their lives (for example, social, cultural, spiritual, and organisational) and to translate their capability (knowledge, skills, understanding) into action (to make things happen and achieve a life they value).

Indigenous Australians came together in a series of workshops (2008–2010) to develop a picture of family and community functioning from their perspectives. Participants were from across a number of jurisdictions and settings, and described the various elements of family and community life essential for high levels of functioning. The workshops identified a number of key themes and weighted these according to their relative value. In 2010, the following six themes were identified by Indigenous Australian participants as key to community functioning:

- connectedness to country, land and history, culture and identity

- resilience

- leadership

- having a role, structure and routine

- feeling safe

- vitality

These themes have been used to analyse and present available data in the ‘Findings’ section of this measure.

The social and cultural determinants of health are closely linked to community functioning and consider health and wellbeing through a holistic, whole-of-life lens incorporating the physical, social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of individuals and their communities. It recognises that health and wellbeing are impacted by, and affect engagement in, education, employment, and broader community activities, as well as connection to culture and Country (DoH 2017).

In particular, Indigenous Australians emphasise the importance of cultural determinants of health. The improvement of outcomes across other determinants of health are brought about by an acknowledgment of the strength of cultural connections to build resilience and the sense of self in individuals. (Biddle Nicholas et al. 2018; DoH 2017). Participation in education, financial independence and human capital development are useful measures, but are often used as measures to define success without reference to culture, language and Country. What success looks like is complex given the diversity and variation across Indigenous communities (Biddle Nicholas et al. 2018).

Community functioning is based on a community’s strengths, but racial discrimination deters and undermines community functioning and increases ill-health (Cunningham & Paradies 2013). In the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (Social Survey), one-third (35%) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 years and over reported being treated unfairly in the last 12 months because they were Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander. These estimates are conservative, with research on racial discrimination reporting 97% of Indigenous Australians surveyed had experienced racism (Kelaher et al. 2014). For further information see measure 3.08 Cultural competency.

Data findings

Outlined below is a description of each of the six themes of community functioning and the key findings for Indigenous Australians. The themes were identified in a series of workshops with Indigenous Australians across the country (Table D1.13.1, Table D1.13.2):

- connectedness to country, land, and history, culture and identity

- resilience

- leadership

- having a role, structure and routine

- feeling safe

- vitality

Connectedness to country, land and history, culture and identity

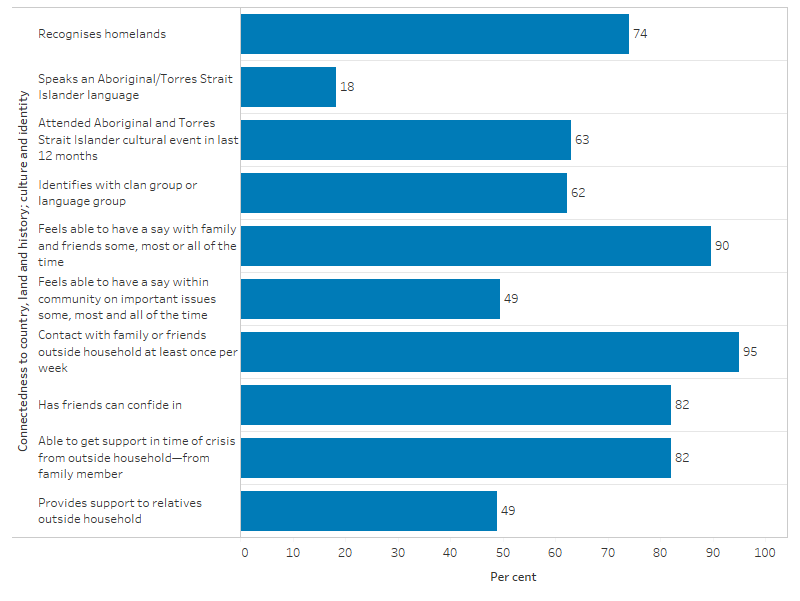

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed:

- 74% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over recognised their homelands.

- 62% of Indigenous Australians identified with a clan or language group.

- 90% of Indigenous Australians felt able to have a say with family and friends, some, most or all the time.

- 95% of Indigenous Australians had contact with family or friends outside the household at least once per week.

- 82% of Indigenous Australians had family or friends they could confide in outside the household.

- 82% of Indigenous Australians were able to obtain support in a time of crisis from a family member living outside the household.

- 63% of Indigenous Australians had attended an Indigenous cultural event in the last 12 months (Table D1.13.3, Figure 1.13.1).

Data from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Health Survey) showed:

- 73% of Indigenous adults reported that they get the emotional support and help they need from their family

- 74% Indigenous adults reported that their family really tries to help them (Table D1.18.40).

Data from the 2012–13 Health Survey showed that 83% of Indigenous adults reported feeling proud of who they are (AHMAC 2017).

Figure 1.13.1: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Connectedness to country, land and history; culture and identity’ for Indigenous Australians, Australia, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

Resilience

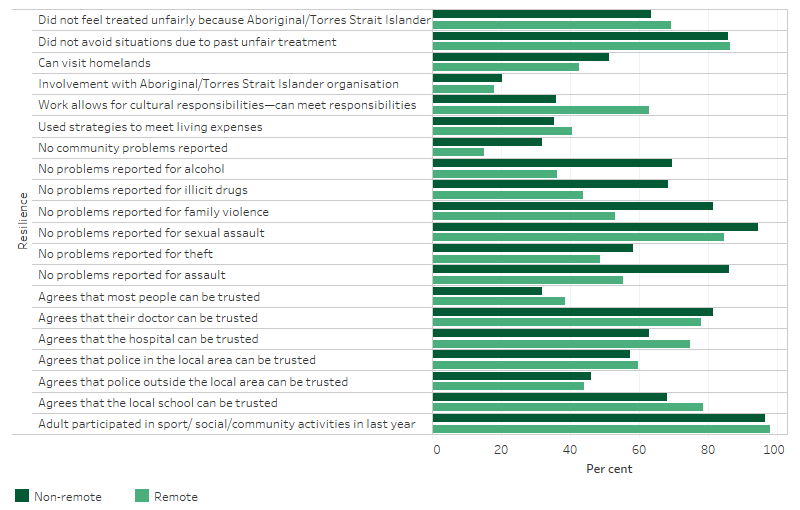

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed:

- 86% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported that they did not avoid situations due to past discrimination

- 81% agreed that their doctor could be trusted and 70% agreed the local school could be trusted.

- 89% were able to find general support from outside the household

- 59% had provided support to someone outside their household in the last 4 weeks

- 97% had participated in sport, social or community activities in the last 12 months

- 41% of employed people said work allowed them to fulfil cultural responsibilities (Table D1.13.4)

- Indigenous Australians living in Remote areas had fewer or no problems reported for alcohol and illicit drugs (36% and 44%, respectively) compared with those living in Non‑remote areas (70% and 68%, respectively)

- Indigenous Australians living in Remote areas had fewer or no problems reported for family violence and assault (53% and 55%, respectively) compared with those living in Non-remote areas (82% and 86%, respectively)

- Indigenous Australians living in Remote areas (79%) were more likely to trust their local school compared with those in Non-remote areas (68%)

- Indigenous Australians living in Remote areas (63%) were more likely to have work that allowed for cultural responsibilities compared with those in Non-remote areas (36%) (Table D1.13.11, Figure 1.13.2).

Figure 1.13.2: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Resilience’ for Indigenous Australians aged 15+, by remoteness, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.11. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

Leadership

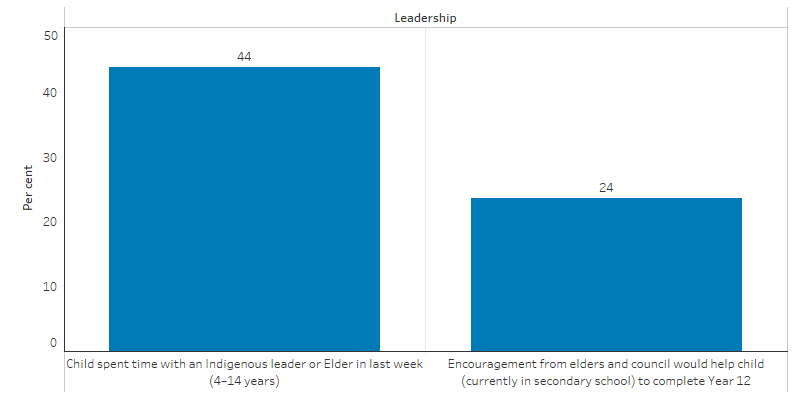

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed 44% of Indigenous children aged 4–14 had spent time with an Indigenous leader or Elder each week (Table D1.13.5, Figure 1.13.3).

Figure 1.13.3: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Leadership’ for Indigenous Australians aged 14 and under, Australia, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

Having a role, structure and routine

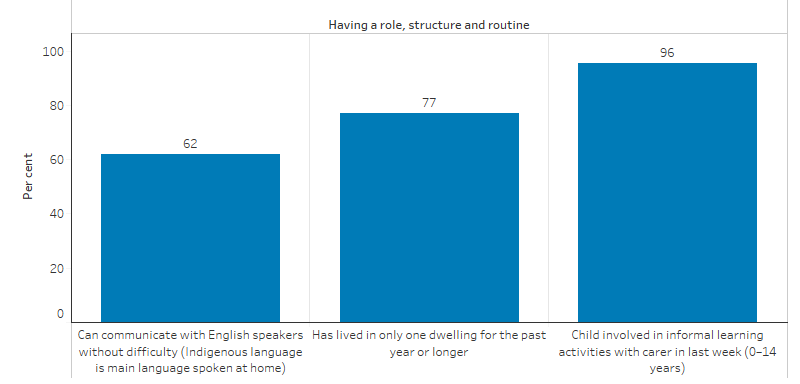

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed:

- 59% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over had not experienced being without a permanent place to live. This was associated with low to moderate levels of psychological distress and very good/excellent health status.

- 72% of Indigenous Australians were in households that had not experienced cash flow problems in the last 12 months

- 85% were in households in which there had been no days without money for basic living expenses in the last 2 weeks

- 96% of children aged 0–14 had participated in informal learning activities with their main carer

- 82% of children aged 0–14 cleaned their teeth once or twice per day (Table D1.13.6, Figure 1.13.4).

Figure 1.13.4: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Having a role, structure and routine’ for Indigenous Australians, Australia, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.6. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

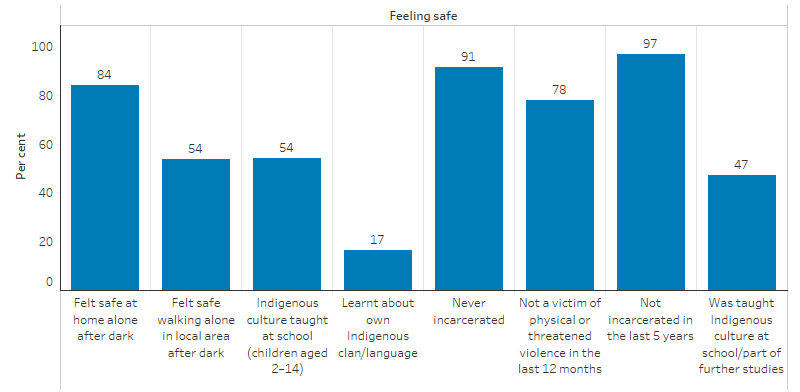

Feeling safe

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed:

- 78% of Indigenous Australians were not a victim of physical or threatened violence in the last 12 months

- 84% of Indigenous Australians felt safe at home alone after dark. This was associated with excellent or very good self-assessed health and low to moderate levels of psychological distress.

- In the five years prior to the survey, 97% of Indigenous Australians had not been incarcerated and 91% had never been incarcerated in their lifetime (Table D1.13.7, Figure 1.13.5).

Figure 1.13.5: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Feeling safe’ for Indigenous Australians, Australia, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.7. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

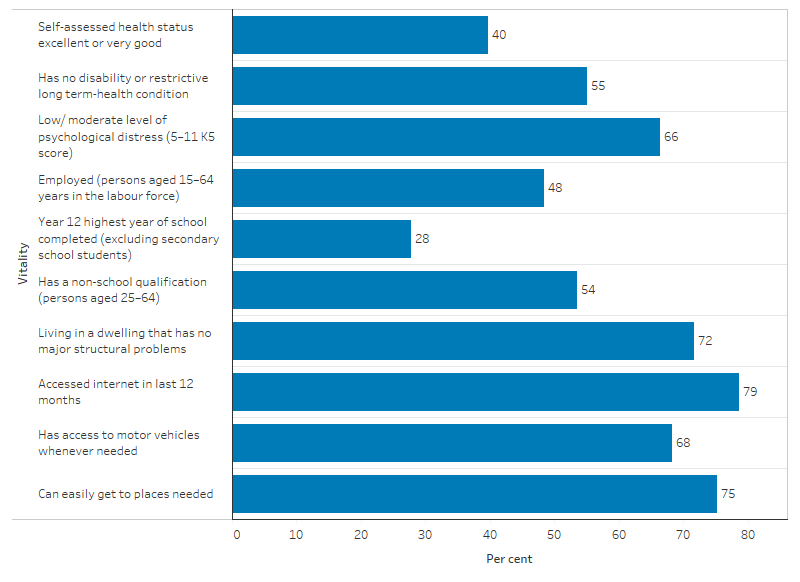

Vitality

Data from the 2014–15 Social Survey showed:

- 66% of Indigenous Australians had experienced low/moderate levels of psychological distress in the four weeks before the survey.

- 68% of Indigenous children aged 0–14 did not have problems sleeping.

- 76% of Indigenous children aged 4–14 spent at least 60 minutes every day being physically active.

- 75% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over said they can easily travel to places as needed. This was associated with feeling able to have a say with family and friends in the community.

- 53% of Indigenous Australians intended to study in the future to improve their knowledge, skills and qualifications.

- 79% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over had accessed the internet in the last 12 months (Table D1.13.8, Figure 1.13.6).

Figure 1.13.6: Variables related to community functioning theme ‘Vitality’ for Indigenous Australians, Australia, 2014–15

Source: Table D1.13.8. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15.

Research and evaluation findings

Biddle (2017) analysed the relationship between measures of community functioning and measures of wellbeing using the 2014–15 Social Survey (Biddle N. 2017). Key findings are summarised below:

- Community functioning was strongly associated with individual measures of wellbeing. People with high levels of all three measures of community functioning (connectedness, resilience and safety) were more likely to be satisfied with their life, more likely to report that they were a happy person all or most of the time, and less likely to report that they felt so sad that nothing could cheer them up.

- High community functioning scores were positively associated with living in Remote areas, post-school qualifications and high income. The young tended to have lower community functioning scores, as did people with relatively low levels of education. People who were not employed and who had changed usual residence also had lower community functioning scores.

- Living in a private rental or state housing were negatively associated with the safety measures, while living in community rentals and overcrowded houses were positively associated with connectedness measures.

- People with a higher community functioning score in the resilience and safety measures were more likely to report that they did not have any barriers to accessing services. However, after controlling for those two measures and a range of demographic, socioeconomic and geographic variables, there was a negative association between connectedness and service access.

- There was no single index that was able to summarise the variation in the community functioning measures. Community functioning is better thought of as a set of themes and related constructs with complex relationships with sociodemographic factors and wellbeing.

There is limited measurable outcome data, beyond Biddle’s 2017 analysis, about the way cultural identity impacts health and wellbeing (Jones et al. 2018; MacLean et al. 2017). In 2017, a systematic review of peer-reviewed articles, which reported quantitative data, concluded “components to enable and support Indigenous peoples to express cultural identity can have positive health and wellbeing effects” (MacLean et al. 2017). The results from this study were mixed and suggest further research is needed to understand this connection in a measurable way.

The National Study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Wellbeing (the Mayi Kuwayu Study), is a new longitudinal study that aims to generate evidence about culture and its relationship with health and wellbeing. As a large scale study, it aims to quantify the ‘associations and pathways between cultural practice and expression, social determinants of health, health behaviours, and health and wellbeing outcomes of Indigenous Australians’. The findings from this study will potentially be a valuable source of information to support policy and program design that is more responsive to the multifaceted and holistic experience of Indigenous Australians (Jones et al. 2018).

A qualitative study with Yaegl Indigenous community members (2006–2010) showed the importance participants placed on relationships for individual and collective strength and functioning. These relationships were essential in the amelioration of risk and adversity, and the community’s sense of wellbeing. The study found that the strengths and resources of a community, including relationships which can be a central component of resilience, need to be recognised and valued in health and mental health initiatives. These resources are potential tools that can be used in risk prevention, strengthening recovery, and enhancing wellbeing (McLennan 2015). Lohoar and colleagues in 2014 showed the strengths of Indigenous cultural practices in family life and child rearing. The study found that culture can be a protective factor for children, families and communities, dependent on necessary social conditions being in place (Lohoar et al. 2014).

Implications

Ultimately, Indigenous Australian communities must define what successful community functioning looks like. Indigenous Australians’ voices, knowledge, expertise and strength, as well as centring Indigenous Australian definitions of success, need to be prioritised throughout the policy cycle. The Yawuru Knowledge Project and the Yawuru Wellbeing Project are two examples of traditional owners exercising self-determination and conceptualising, defining and measuring their wellbeing (Yap & Yu 2016). Yawuru wellbeing indicators were developed from the ground up, working with the Yawuru in Broome. These projects demonstrate the importance of Indigenous participation in all aspects of the knowledge process, so that Indigenous Australian communities can set their own development agenda and determine what their needs are to inform their planning and program design.

Genuine partnerships with Indigenous Australians and Indigenous communities that enable shared decision making and recognise, respect and incorporate Indigenous cultures are essential. Co-design and co‑delivery through community empowerment and place‑based partnership models are needed to drive better public sector collaboration across all levels of government. Empowered Communities involves Indigenous communities and governments working together to set priorities, improve services and apply funding effectively at a regional level. Importantly, it aims to increase Indigenous ownership and give Indigenous Australians a greater say in decisions that affect them. Governments must leverage mainstream policies and programs for better outcomes for Indigenous Australians, while supporting locally‑driven solutions.

The new National Agreement on Closing the Gap was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The Agreement has recognised that strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures are fundamental to improved life outcomes for Indigenous Australians and that all activities to be implemented under the Agreement need to support, and promote and not diminish these cultures. In particular, the Agreement has established the following outcomes to support the cultural wellbeing of Indigenous Australians:

- Outcome 15 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people maintain a distinctive cultural, spiritual, physical and economic relationship with their land and waters.

- Target – By 2030, a 15 per cent increase in Australia’s landmass subject to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s legal rights or interests.

- Target – By 2030, a 15 per cent increase in areas covered by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people’s legal rights or interests in the sea.

- Outcome 16 – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and languages are strong, supported and flourishing.

- Target – By 2031, there is a sustained increase in number and strength of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages being spoken.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023 draws attention to ‘the centrality of culture in the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the rights of individuals to a safe, healthy and empowered life’. The Health Plan builds on existing strategies and planning approaches to improving Indigenous health. Achieving improvements in health outcomes for Indigenous Australians means working towards a culturally respectful and non-discriminatory health system, where all Indigenous Australians have access to health services that are culturally safe, high quality, evidence-based and responsive. Beginning in late 2020, the Health Plan will undergo a refresh. The refreshed Health Plan will embed the cultural determinants and social determinants of health and provide a single, overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health with a vision that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples enjoy long, healthy lives that are centred in culture, with access to services that are prevention-focused, responsive, culturally safe, and free of racism and inequity. More information on the Health Plan is in Policies and strategies.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- AHMAC 2017. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report 2017. Canberra: AHMAC.

- AIHW 2014. Determinants of wellbeing for Indigenous Australians. Cat. no. IHW 137. Canberra: AIHW.

- Biddle N 2017. Community functioning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: Analysis using the 2014/15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey. Canberra: (unpublished).

- Biddle N, Gray M & Schwab RJ 2018. Measuring and analysing success for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

- Cunningham J & Paradies YC 2013. Patterns and correlates of self-reported racial discrimination among Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, 2008-09: analysis of national survey data. International Journal for Equity in Health 12:47.

- DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) 2017. My Life My Lead - Opportunities for strengthening approaches to the social determinants and cultural determinants of Indigenous health: Report on the national consultations December 2017. Canberra.

- Jones R, Thurber KA, Chapman J, D’Este C, Dunbar T, Wenitong M et al. 2018. Study protocol: Our Cultures Count, the Mayi Kuwayu Study, a national longitudinal study of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander wellbeing. BMJ Open 8.

- Kelaher MA, Ferdinand AS & Paradies Y 2014. Experiencing racism in health care: The mental health impacts for Victorian Aboriginal communities. The Medical Journal of Australia 201:44-7.

- Lohoar S, Butera N & Kennedy E 2014. Strengths of Australian Aboriginal cultural practices in family life and child rearing. Canberra: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- MacLean S, Ritte R, Thorpe A, Ewen S & Arabena K 2017. Health and wellbeing outcomes of programs for Indigenous Australians that include strategies to enable the expression of cultural identities: a systematic review. Australian journal of primary health 23:309-18.

- McLennan V 2015. Family and community resilience in an Australian Indigenous community. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin 15.

- Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2004. Defining the Domains: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework. (ed., Department of Health and Ageing). Canberra: DoHA.

- Sen A 1999. Development As Freedom Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Taylor J, Edwards J, Champion S, Cheers S, Chong A, Cummins R et al. 2012. Towards a conceptual understanding of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community and community functioning. Community Development Journal 47:94-110.

- Yap M & Yu E 2016. Community wellbeing from the ground up: a Yawuru example. Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre Research Report 3/16 August.