Key messages

- According to the ABS Census of Population and Housing, between 2011 and 2021 the number of people reporting they were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers increased from 1,256 to 1,741. However, this was outpaced by population growth, with the rate of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over decreasing from 36 Indigenous Health Workers per 10,000 population in 2011, to 32 per 10,000 population in 2021.

- Indigenous Australians were more likely than non-Indigenous Australians to live in areas facing a supply challenge for at least one health profession (20% compared with 3%), based on analysis of data from the 2014 National Health Workforce Data Set and adjusting for land size, population dispersion, and the proximity of the population to the relevant service locations.

- According to data from the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency, the number of registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners increased from 514 in 2015 to 792 in 2021.

- The clinical FTE rate for psychologists decreased with increasing proportion of the population who are Indigenous – from 109 per 100,000 population in areas where less than 1% of the population was Indigenous, to 30 per 100,000 in areas where 20% or more of the population was Indigenous.

- The clinical FTE rate for pharmacists in areas where less than 1% of the population were Indigenous was 103 per 100,000 population, compared with 59 per 100,000 population in areas where 20% or more of the population was Indigenous. It ranged between 76 and 88 FTE per 100,000 population in other areas.

- In contrast, the clinical FTE rate for employed general practitioners (GPs), nurses and midwives, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers, were all highest in areas where more than 20% of the population were Indigenous.

- The number of FTE staff working in Indigenous primary health-care services varied across remoteness areas, ranging from 1,580 staff employed in Outer regional areas to 2,066 in Inner regional areas.

- In the decade from 2012–13 and 2021–22, there was an increase of 21% in the number of FTE staff in these organisations.

- Despite growth in some areas, the vacancy rates for health/clinical staff positions and administrative and support staff positions increased over the decade from 2013 and 2022. The vacancy rates for full-time health and clinical positions grew from 6.1% to 10.8%, while administrative and support position grew from 1.0% to 4.5%.

- As at 30 June 2022, vacancies for health/clinical staff positions in Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations were highest for nurses (146 FTE), followed by social and emotional wellbeing workers (80 FTE), and doctors (63 FTE). Vacancies for positions for Aboriginal health practitioners and health workers (which can only be held by Indigenous Australians) were 43% and 42%, respectively.

- Based on the 2017–18 data, in Remote areas 81% of Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported that recruitment, training and support of Indigenous staff was a major challenge, as did 77% of those in Very remote areas. In relation to all staff, retention and turnover were reported as a challenge by 54% of organisations; the proportion was highest in Remote (73%) and Very remote areas.

- In the Northern Territory, where the majority of services are located in Remote or Very remote areas, recruitment, training and support services was a challenge for 84% of services, and staff retention and turnover was reported as a challenge by 79% of services.

Why is it important?

There is a growing recognition of the array of factors that affect the health status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, including differences in the social determinants of health, availability and accessibility of culturally appropriate health services, and other biomedical, behavioural, and environmental factors (DoH 2013).

The capacity to recruit and retain non-Indigenous staff who are culturally safe is essential for health services to deliver appropriate, continuous and sustainable health care for Indigenous Australians. Staff recruitment and retention are particularly important in rural and remote areas to ensure Indigenous Australians in these areas have access to health professionals for their health care needs (Humphreys et al. 2009). Almost two-thirds of Indigenous Australians live in regional and remote areas, and Indigenous Australians make up 30% of the total population in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined) (ABS 2018).

Indigenous Australians are under-represented in the health workforce. One way of supporting culturally appropriate and safe health services is for the government to support a skilled Indigenous Australian health workforce through the implementation of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce Strategic Framework and Implementation Plan 2021–2031 (the Workforce Plan) (see measure 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce). Indigenous Australians respond better to health care when it is delivered in a culturally safe and appropriate way. Indigenous health professionals have a strong capacity to deliver culturally responsive care in addition to any clinical care they may also be delivering and can improve the cultural security of health care and reduce discharge against medical advice (Taylor et al. 2009). An Indigenous health workforce also helps to strengthen the cultural safety of the broader health teams and organisations in which they work. While the Indigenous workforce plays a vital role in the provision of culturally safe services, it is the responsibility of the health care system to ensure that mainstream health services are culturally safe through high-quality professional development and training, appropriate management when cultural respect is lacking, and staff developing awareness of their own unconscious bias (AHMAC 2016).

Data findings

Medical practitioners

Based on data from the National Health Workforce Data Set, in 2021, there were 111,654 medical practitioners registered in Australia (excluding provisional registrants) in the medical workforce, 92% (103,091) of whom were employed as clinicians. Registered medical practitioners not in the medical workforce included those who were retired (1,862), overseas (1,365) or not looking for work in medicine (1,551) (Table D3.22.1).

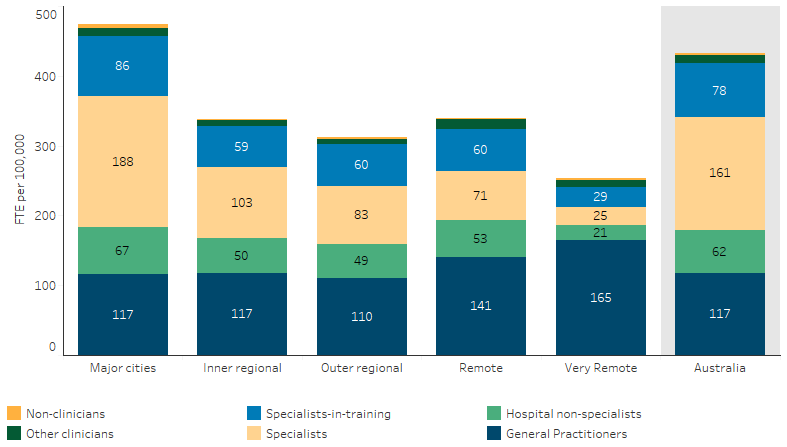

In 2021, the rate of employed medical practitioners across Australia was 433 full-time equivalent (FTE) per 100,000 population. Relative to population size, Major cities had the highest rate of employed medical practitioners (474 FTE per 100,000), with the lowest rate in Very remote areas (253 FTE per 100,000) (Table D3.22.14).

Looking at the area of main practice of medical practitioners, general practitioner (GP) FTE rates were higher in remote than non-remote areas. There were 165 GP FTE per 100,000 in Very remote areas, followed by 141 FTE per 100,000 in Remote areas. In comparison, across non-remote areas, there were 110 GP FTE in Outer regional areas and 117 FTE per 100,000 in both Inner regional areas and Major cities (Table D3.22.14). However, care should be taken in interpreting these data, as work arrangements in remote areas can be more complicated in ways not captured by the data (NRHA 2017). For example, the average reported hours a GP works per week generally increases with remoteness, which may be due to factors such as greater distances to travel (so more non-clinical hours). Also, people living in remote areas may face additional barriers to accessing a GP, for example, due to greater geographic spread and travel distances. Previous modelling work by the AIHW has shown that, on average, access to GPs worsens with increasing remoteness (AIHW 2014).

The supply of clinical specialists declined with increasing remoteness, from 188 FTE per 100,000 in Major cities to 25 FTE per 100,000 in Very remote areas (Table D3.22.14, Figure 3.22.1).

Figure 3.22.1 Employed medical practitioners, FTE per 100,000 population, by main area of practice and remoteness area, 2021

Source: Table D3.22.14. AIHW analysis of National Health Workforce Data Set.

In 2021, the rate of employed medical practitioners across Australia was 433 FTE per 100,000 population, an increase from 382 FTE per 100,000 in 2013 (Table D3.22.15).

By main area of practice, the rate of GPs increased from 111 FTE per 100,000 in 2013 to 117 FTE per 100,000 in 2021. Clinical specialists increased from 139 FTE per 100,000 to 161 FTE per 100,000 over the same period (Table D3.22.15).

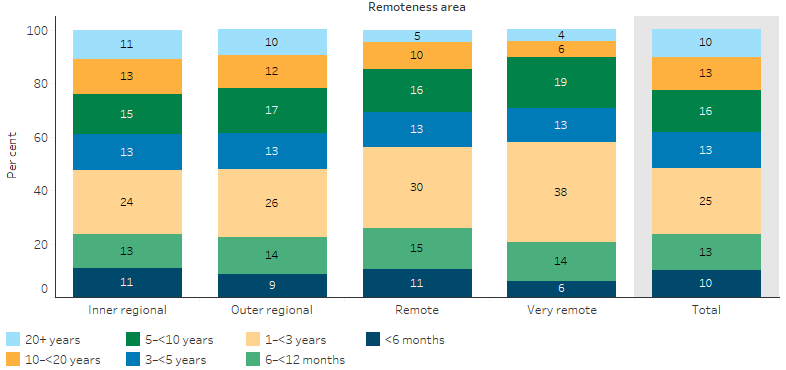

A national survey of the rural workforce in November 2016 found that of the 8,329 GPs working in rural Australia, an estimated 48% had been in their current practice for fewer than 3 years (56% in Remote areas and 58% in Very remote areas) (Table D3.22.4, Figure 3.22.2). It also found that 58% of GPs working outside metropolitan areas were males; this increased to 62% in Very remote areas.

Figure 3.22.2: Proportion of GPs in rural and remote areas, by length of stay in current practice and remoteness, 30 November 2016

Source: Table D3.22.21. Medical practice in rural and remote Australia: Combined Rural Workforce Agencies National Minimum Data Set report as at 30 November 2016.

Relationship to distribution of Indigenous population

Looking at FTE rates at a national level can mask variation in the supply of the health workforce at small local area levels.

The Geographically-adjusted Index of Relative Supply (GIRS) is a measure developed by the AIHW to compare health workforce supply across small geographic areas. Geographic areas are categorised based on Statistical Areas 2 (SA2). SA2s are medium-sized geographical areas that represent communities that interact together socially and economically. SA2s generally have a population between 3,000 and 25,000 with an average of about 10,000 people. The GIRS was calculated using data on hours worked in clinical roles and on main practice location from the 2014 National Health Workforce Data Set and adjusting this for three other factors – land size, population dispersion, and the proximity of the population to the relevant service locations.

The GIRS score ranges from 0 to 8 for each geographic area, and can vary for different professions. Areas with lower GIRS scores are more likely to face workforce supply challenges than those with higher GIRS scores.

GIRS scores were calculated for GPs, nurses, midwives, pharmacists, dentists, psychologists and optometrists. For example, for GPs, there were 39 SA2s with GIRS scores of 0–1 (higher probability of workforce supply challenges). Of these, the majority (23) were in Very remote areas, along with 7 in Remote areas, 6 in Outer regional areas and 3 in Inner regional areas (AIHW 2016).

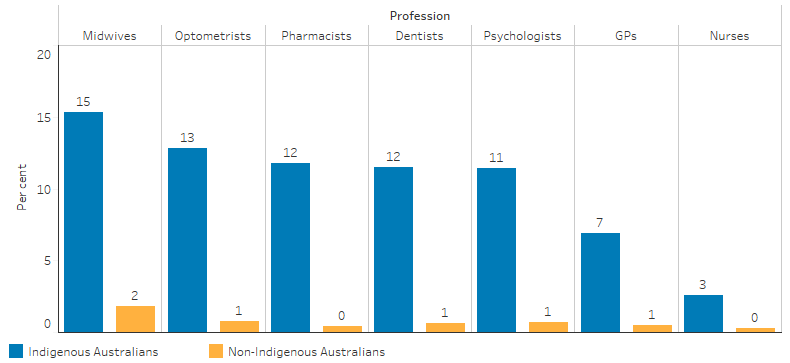

The GIRS scores were also compared with the distribution of the Indigenous population to assess the extent to which Indigenous Australians live in areas with lower relative levels of supply of health professionals. These scores showed that GIRS scores of 0 to 1 occur most often for midwives (15%), optometrists (13%), pharmacists (12%) and least often for nurses (3%) (Figure 3.22.3). Nearly 20% of Indigenous Australians lived in areas facing a supply challenge for at least one health profession, compared with 3% of the non-Indigenous population (AIHW 2016).

Figure 3.22.3: Proportion of population living in areas of lowest relative clinical workforce supply, by Indigenous status and profession

Note: For midwives, the GIRS score was calculated for women aged 15-44.

Source: AIHW Spatial distribution of the supply of the supply of clinical health workforce 2014: relationship to the distribution of the Indigenous population. Cat. No. AIHW 170. Canberra: AIHW; 2016.

It is also possible to look at the supply of the health workforce relative to the proportion of the population who are Indigenous in that area.

Health workforce data for 2021, at SA3 level, was analysed to look at how the FTE rate of registered health professionals varies according to the proportion of the population who are Indigenous. SA3s are geographic areas built from the whole SA2 through aggregating groups of SA2s that have similar regional characteristics. SA3s generally have an average total population between 30,000 and 130,000 people. This showed, that in 2021:

- the clinical FTE rate for psychologists decreased with increasing proportion of the population who are Indigenous – from 109 per 100,000 population in areas where less than 1% of the population was Indigenous, to 30 per 100,000 in areas where 20% or more of the population was Indigenous (D3.22.17)

- the clinical FTE rate for pharmacists in areas where less than 1% of the population were Indigenous was 103 per 100,000 population, compared with 59 per 100,000 population in areas where 20% or more of the population was Indigenous. It ranged between 76 and 88 FTE per 100,000 population in other areas (D3.22.18).

In contrast, the clinical FTE rate for employed GPs, nurses and midwives, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers, were all highest in areas where more than 20% of the population were Indigenous (Tables D3.22.2, D3.22.26, D3.22.27).

Indigenous primary health care organisations

As at 30 June 2022, there were 5,558 FTE health/clinical staff and 4,053 FTE administrative and support staff positions within Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations. The vacancy rate was 11% for health/clinical staff positions and 4.5% for administrative and support staff positions (Table D3.22.11).

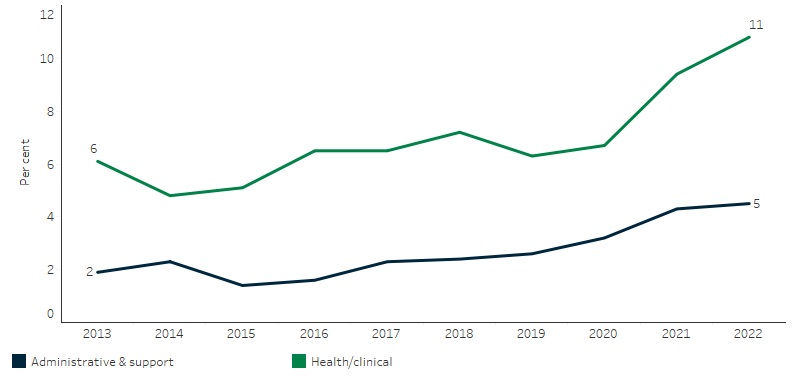

Nationally, the vacancy rates for health/clinical staff positions and administrative and support staff positions increased over the decade from 2013 and 2022. The vacancy rates for full-time health and clinical positions grew from 6.1% to 10.8%, while administrative and support positions grew from 1.0% to 4.5% (Table D3.22.12, Figure 3.22.4).

Figure 3.22.4: Proportion of FTE vacant positions in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health-care organisations, by position type, at 30 June 2013 to 30 June 2022

Source: Table D3.22.12. AIHW analysis of Service Activity Reporting, Drug and Alcohol Services Reporting and AIHW Online Services Report data collections.

As at 30 June 2022, vacancies for health/clinical staff positions in Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations were highest for nurses (146 FTE), followed by social and emotional wellbeing workers (80 FTE), and doctors (63 FTE). Vacancies for positions for Aboriginal health practitioners and health workers (which can only be held by Indigenous Australians) were 43% and 42%, respectively.

Vacancies for administrative and support staff positions in Indigenous primary health-care organisations (which can be held by Indigenous or non-Indigenous Australians) were highest for financial and accounting (72 FTE), followed by manager/supervisors (55 FTE) (Table D3.22.11).

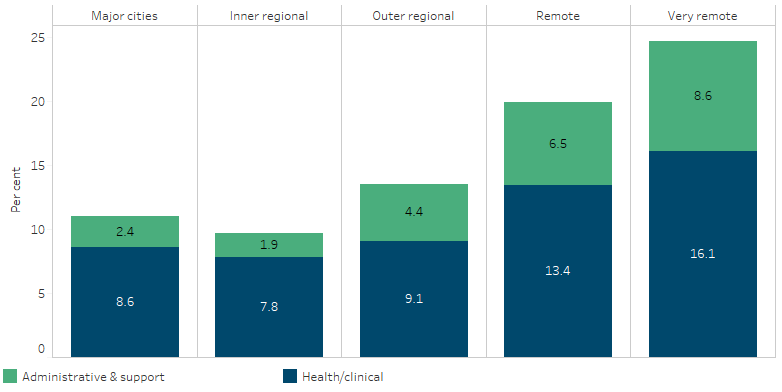

As at 30 June 2022, the proportion of health/clinical staff positions that were vacant ranged from 16% in Very remote areas to 7.8% in Inner regional areas. For administrative and support staff positions, vacancies were also highest in Very remote areas (8.6%) and lowest in Inner regional areas (1.9%) (Table D3.22.23, Figure 3.22.5).

Figure 3.22.5: Proportion of FTE vacant positions in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health-care organisations, by remoteness area and position type, at 30 June 2022

Source: Table D3.22.23. AIHW analysis of Service Activity Reporting, Drug and Alcohol Services Reporting and AIHW Online Services Report data collections.

In 2017–18, 71% (141 services) of Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported that recruitment, training and support of Indigenous staff was a major challenge. Collection of these data ceased after the 2017–18 Online Services Report collection, so no updates are available. Based on the 2017–18 data, in Remote areas 81% of Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported that recruitment, training and support of Indigenous staff was a major challenge, as did 77% of those in Very remote areas. In relation to all staff, retention and turnover were reported as a challenge by 54% of organisations; the proportion was highest in Remote (73%) and Very remote areas (75%) (Table D3.22.25).

In the Northern Territory, where the majority of services are located in Remote or Very remote areas, recruitment, training and support services was a challenge for 84% of services, and staff retention and turnover was reported as a challenge by 79% of services (Table D3.22.24).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Practitioners

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners play essential roles in ensuring culturally appropriate care for Indigenous Australians. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers have completed a Certificate II or higher in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care, but are not registered health professionals (AHPRA 2020; DoHAC 2021). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners have a Certificate IV in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care Practice, and are required to be registered with the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (and so are in scope of the National Health Workforce Data Set). To be eligible to apply for registration as an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioner, a person must provide evidence that they are of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander descent, identify as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person, and be accepted as an Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander person in the community in which they live or did live (DoHAC 2021). Based on the National Health Workforce Data Set, the number of registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners increased from 514 in 2015 to 792 in 2021 (AHPRA 2022).

In the ABS Census of Population and Housing, data on self-reported employment and occupation is collected. From this source, data are available for the occupation category ‘Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker’. Between 2011 and 2021, the number of people reporting they were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers increased from 1,256 to 1,741 (Table D3.12.12). However, this was outpaced by population growth, with the rate of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over decreasing from 36 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers per 10,000 population in 2011, to 32 per 10,000 population in 2021.

Research and evaluation findings

Jongen and colleagues (2019) noted that the capacity of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) to meet the needs of Indigenous Australians relies on the skills, motivation and experience of its workforce. ACCHSs already implement workforce-development strategies while also facing challenges to maintain a strong and stable workforce (Jongen et al. 2019). Challenges and strategies for ACCHSs include; improving workforce conditions; increasing remuneration; building strong leadership through clear communication and strong management and supervision; improving professional development opportunities using training and career progression pathways; and supporting teamwork through meetings, mentoring and support. Conway and colleagues (2017) also noted the importance of; improved support for Indigenous health workers; the inclusion of Indigenous health workers in decision-making within the health care setting; ‘champions’ to support Indigenous health workers in the implementation of chronic disease care self-management programs; and adequate Indigenous representation in allied health and management positions (Conway et al. 2017).

A Senate inquiry into factors affecting the supply of health services and medical professionals in rural areas has identified a complex interplay between environmental, personal and work-related factors (Senate Community Affairs Committee Secretariat 2012). These include access to professional development and career progression, remuneration, heavy workloads, on-call hours, loss of anonymity, social barriers and professional isolation, opportunities for spouses and children, and access to appropriate, affordable and secure accommodation.

A growing trend towards medical specialisation was identified as reducing generalist training pathways and affecting the supply of GPs in rural and regional areas—the area of medical practice most required in these areas (Senate Community Affairs Committee Secretariat 2012). Conversely, rural lifestyle, diverse caseloads, autonomy and community connectedness have been cited as motivation incentives for allied health professionals to work in remote and rural areas (Campbell et al. 2012).

A 2015 study on GP mobility found that GPs working in small communities and those in rural locations for fewer than 3 years are most at risk of leaving rural practice. Younger rural GPs were also more likely to leave rural practice than were older rural GPs (McGrail & Humphreys 2015).

A national study of work-life conditions and satisfaction undertaken on the factors affecting the recruitment and retention of junior doctors in rural areas found that work-life balance, professional development opportunities, positive community relationships, and adequate support structures significantly influence doctors' decisions to stay in rural areas. Furthermore, satisfaction levels of rural practitioners were found to be higher than their urban counterparts, largely due to the rewarding nature of rural practice and a strong sense of community (Lennon M et al. 2019). This research suggests emphasising the benefits of rural work and mitigating weaknesses may help to attract more early-career doctors to regional areas.

A 2007 study identified that doctors who were satisfied with their current medical practice said they would remain in rural practice for longer than those who were not satisfied (11.5 years compared with 8.2 years). GPs content with their lives as rural doctors intended to remain in rural practice 51% longer than those who were not content (11.8 compared with 7.8 years) (Alexander & Fraser 2007).

A study of drug and alcohol workers found that Indigenous workers experienced above-average levels of job satisfaction and relatively low levels of exhaustion; however, they also experienced lower levels of mental health and wellbeing and greater work–family imbalance. The report highlighted the importance of workforce-development strategies that focus on culturally appropriate, equitable and supportable organisational conditions, including addressing stress, salaries, benefits and opportunities for career and personal growth (Roche et al. 2013).

Implications

Recruitment and retention of GPs, nurses and allied health professionals are significant issues for health services located in rural and remote Australia. Ongoing support for rural and remote GP vocational training opportunities and the selection of medical students from these areas are critical in addressing these issues (McGrail et al. 2016).

The Australian Government, in collaboration with various stakeholders, has embarked on several initiatives aimed at enhancing the recruitment of Indigenous Australians within the healthcare sector. This includes the provision of support to organisations like the four Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Professional Organisations (ATSIHPOs) for programs and initiatives designed to support Indigenous students pursuing health careers. A key scheme aimed at improving healthcare accessibility and workforce distribution in rural and remote Australia is the Medical Rural Bonded Scholarship (MRBS) Scheme. This program provides scholarships to medical students who commit to working in rural areas after completing their training. It was reformed in 2020 to offer more flexibility to scholars in their service return period (DoHAC 2023). Another similar initiative is the Bonded Medical Program (BMP), providing Commonwealth Supported Places to medical students who commit to work in under-served areas (DoHAC 2020) Additional supportive measures such as increased funding for scholarships, traineeships, and mentorship programs for Indigenous Australians, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Entry Pathway in universities, collectively work towards improving the representation and participation of Indigenous Australians in the healthcare sector.

The Australian Government has committed to the First Nations Health Worker Traineeship Program, which will be delivered by the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation (NACCHO). The Program will support up to 500 Indigenous Australian trainees to undertake Certificate III or IV accredited training to enable them to work across various health settings and be able to deliver culturally appropriate care to Indigenous Australians.

More information is required to develop an understanding of the retention and turnover of staff in Indigenous-specific primary health care services and how this compares with mainstream services. Further understanding of the enablers and barriers of retention would assist in the development and implementation of retention strategies. Succession plans, clear career pathways and support for ongoing professional development in strengthening clinical and non-clinical skills and capabilities, and ensuring organisational cultural safety, are mechanisms suggested to improve recruitment and retention. In particular, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workforce Plan 2021–2031 (Workforce Plan) has identified in Strategic Direction 3 that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are to be employed in culturally safe and responsive workplace environments that are free of racism across health and all related sectors.

Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health as an identifiable specialty is also important in improving services and retaining highly skilled clinicians to build the capacity of the workforce in Indigenous health. There have been calls for the development of a subspecialty in Indigenous health for GPs and physicians, supported by medical colleges. This would recognise the unique skills needed to work in Indigenous health and ensure that practitioners would receive appropriate training. The need to improve the attraction of working in Indigenous health has been recognised.

Participation by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers in decision-making in and around health service provision will improve cooperation and collaboration within a health care team (particularly those that include non-Indigenous health professionals) in delivering quality and culturally safe health care (Durey et al. 2012).

Collaboratively designed, implemented and evaluated retention strategies will assist in determining which strategies are most effective at retaining Indigenous Australians in the health workforce (Lai et al. 2018). The Workforce Plan was informed by an extensive national co-design process. This design process identified that improved recruitment and retention of Indigenous Australians requires a culturally safe health and education sector, and in order to successfully grow the Indigenous health workforce, barriers to education, employment and career progression need to be addressed consistently at both the national and jurisdictional level.

Attracting and retaining culturally safe non-Indigenous health professionals to work in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health settings as well as Indigenous Australian health workers may help relieve pressure among existing Indigenous Australian health workers (see measures 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce and 3.20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples training for health-related disciplines).

Under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, parties to the Agreement committed to building strong Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community controlled sectors that include dedicated and identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforces. Supporting this commitment, a three-year Health Sector Strengthening Plan was agreed in December 2021 by the Closing the Gap Joint Council. This Plan outlines actions that will support and build the Aboriginal community controlled health sector, including four actions targeted to workforce.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2016. ABS Canberra.

-

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council) 2016. Cultural Respect Framework 2016-2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Canberra: AHMAC.

-

AHPRA (Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency) 2020. Professional capabilities for registered Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Practitioners. AHPRA. Viewed 9 June 2023.

-

AHPRA 2022. Supporting access to safe and professional healthcare annual report 2021/22. Ahpra.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2014. Access to primary health care relative to need for Indigenous Australians. Cat. no. IHW 128. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2016. Spatial distribution of the supply of the clinical health workforce 2014: relationship to the distribution of the Indigenous population. Cat. no. IHW 170. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2018. Australia’s health 2018. Australia’s health series no. 16. AUS 221. Canberra: AIHW.

- Alexander C & Fraser JD 2007. Education, training and support needs of Australian trained doctors and international medical graduates in rural Australia: a case of special needs. Rural and Remote Health 7:681.

- Campbell N, McAllister L & Eley D 2012. The influence of motivation in recruitment and retention of rural and remote allied health professionals: a literature review. Rural and Remote Health 12:1900.

- Conway J, Tsourtos G & Lawn S 2017. The barriers and facilitators that indigenous health workers experience in their workplace and communities in providing self-management support: a multiple case study. BMC health services research 17:319.

- DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) 2013. National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- DoH 2019. Health Workforce Data Summary Statistics.

-

DoHAC (Department of Health and Aged Care) 2020. Bonded Medical Program.

DoHAC 2021. About the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workforce. Canberra: Department of Health and Aged Care.

DoHAC 2023. Medical Rural Bonded Scholarship Scheme.

- Durey A, Wynaden D, Thompson SC, Davidson PM, Bessarab D & Katzenellenbogen JM 2012. Owning solutions: a collaborative model to improve quality in hospital care for Aboriginal Australians. Nursing Inquiry 19:144-52.

- Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Kuipers P, Wells R, Russell D, Siegloff S et al. 2009. Improving workforce retention: Developing an integrated logic model to maximise sustainability of small rural & remote health care services document on the Internet]. c2009 [cited 2014 Nov 17]. Canberra: Australian Primary Health Care Research Institute.

- Jongen C, McCalman J, Campbell S & Fagan R 2019. Working well: strategies to strengthen the workforce of the Indigenous primary healthcare sector. BMC health services research 19:910.

- Lai G, Taylor E, Haigh M & Thompson S 2018. Factors affecting the retention of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce: a systematic review. International journal of environmental research and public health 15:914.

-

Lennon M, O'sullivan B, McGrail M, Russell D, Suttie J & Preddy J 2019. Attracting junior doctors to rural centres: A national study of work-life conditions and satisfaction. Australian journal of Rural Health 27:482-8.

- McGrail MR & Humphreys JS 2015. Geographical mobility of general practitioners in rural Australia. The Medical Journal of Australia 203:92-7.

- McGrail MR, Russell DJ & Campbell DG 2016. Vocational training of general practitioners in rural locations is critical for the Australian rural medical workforce. Medical Journal of Australia 205:216-21.

-

NRHA (National Rural Health Alliance) 2017. Health Workforce. NRHA. Viewed 30 May 2023.

- Roche AM, Duraisingam V, Trifonoff A & Tovell A 2013. The health and well-being of Indigenous drug and alcohol workers: results from a national Australian survey. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 44:17-26.

- Senate Community Affairs Committee Secretariat 2012. Community Affairs References Committee: The factors affecting the supply of health services and medical professionals in rural areas. (ed., Senate Standing Committees on Community Affairs). Canberra: SSCCA.

- Taylor KP, Thompson SC, Wood MM, Ali M & Dimer L 2009. Exploring the impact of an Aboriginal Health Worker on hospitalised Aboriginal experiences: lessons from cardiology. Australian Health Review 33:549-57.