Key messages

- For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, suicide was the leading cause of death due to injury and poisoning (38% or 847 deaths) in 2015–2019. It was followed by transport accidents (19% or 417 deaths), accidental poisoning (18% or 413 deaths) and assault (7.8% or 174 deaths).

- For Indigenous males, rate for deaths from suicide was 2.7 times the rate for Indigenous females. This was followed by accidental drowning, with the rate for Indigenous males being 2.5 times the rate for Indigenous females.

- Over the decade 2010 to 2019, the age-standardised death rate due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians increased by 14%. The rate for non-Indigenous Australians also increased (by 8%), with no significant change in the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

- In 2015–2019, of all deaths from injury and poisoning, transport accidents was the most common cause for those aged 5–14 (33% of all injury and poisoning deaths) while suicide was the leading cause for those aged 15–44 (ranging from 69% for the 15–19 year age group to 32% for the 35–39 age group).

- Over the period July 2017 to June 2019, there were 73,641 (44 per 1,000) hospitalisations due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians.

- Falls were the leading cause of hospitalisation due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous males (21%) and the second leading cause for Indigenous females (21%). Assault was the leading cause of hospitalisation due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous females (22%) and the second leading cause for Indigenous men (16%).

- Hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians increased by 34% over the decade from 2009–10 and 2018–19, noting that some of this increase was due to a change in coding of hospitalisations for rehabilitation from July 2015.

- Indigenous Australians were 1.8 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for injury and poisoning between July 2017 and June 2019. The age-standardised rate of injury and poisoning hospitalisations increased faster for Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians over the decade to 2018–19 resulting in a widening of the gap from 15 per 1,000 in 2009–10 to 24 per 1,000 in 2018–19.

Why is it important?

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, external causes (injury and poisoning) is currently the third highest cause of deaths, and death rates are twice as high as rates for non-Indigenous Australians. Suicide (intentional self-harm) is the leading cause of death from external causes followed by transport accidents (see measures 1.23 Leading causes of mortality and 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing) (MacRae et al. 2013).

Injuries can cause long-term disability and disadvantage including reduced opportunities in education and employment, communication impairment and burden on caregivers (Stephens et al. 2014). Evidence shows that acquired brain injury leading to cognitive impairment is associated with contact with the criminal justice system (Haysom et al. 2014). Injury is a significant health issue for Indigenous Australians and rates of injury for specific causes are many times those for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2019a). Indigenous Australian children suffer a disproportionately high burden of unintentional injury (Möller et al. 2017).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), released in December 2021, provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. The Health Plan is aligned with the National Injury Strategy 2020–2030.

Priority 4 of the Health Plan, Health promotion, is about enabling people to be in control of their health. Health promotion, literacy and prevention approaches recognise culture as a protective factor and prioritise strategies that drive improved outcomes across the cultural determinants and social determinants of health. Health promotion also involves strengths-based harm reduction policies and programs, including those that address the risk factors associated with injury. One objective of Priority 4 addresses injury prevention:

- Objective 4.7. Deliver targeted, culturally safe and responsive injury prevention activities.

Priority 10 of the Health Plan focuses on mental health and suicide prevention. A number of objectives focus on suicide prevention, including strengthening suicide prevention services and implementing key reforms to Indigenous mental health and suicide prevention policy.

Burden of disease

In 2018, injuries were the second leading cause (12%) of the total disease burden for Indigenous Australians, behind mental and substance use disorders (23%). Most of the injury burden (89%) was due to premature death (fatal burden (YLL)), with only 11% due to years lived in ill health or with disability (non-fatal burden (YLD)). Injuries were the leading cause of the fatal burden in 2018 (23% of fatal burden) (AIHW 2022).

Just over two-thirds (69%) of the total burden (DALY) due to injuries was experienced by Indigenous males (with remaining 31% by Indigenous females). Among Indigenous males, 16% of total burden was due to injuries, compared with 8.3% for Indigenous females.

The leading causes of injury burden were suicide and self-inflicted injuries (37% of total injury burden), and poisoning (such as the toxic effects of medicinal or other substances) (17% of injury burden).

Injuries accounted for 10% of the gap in disease burden between Indigenous and non‑Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022).

Data findings

Death due to injury and poisoning

Deaths data in this measure are from five jurisdictions for which the quality of Indigenous identification in the deaths data is considered to be adequate; namely, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Data by remoteness are reported for all Australian states and territories combined (see Data sources: National Mortality Database).

Over the period 2015–2019, among Indigenous Australians:

- looking at broad causes of death, injury and poisoning was the third leading cause of death accounting for 15% (2,240) of all deaths, following cancer (including other neoplasms; 23% of total deaths) and cardiovascular disease (23%). Of injury and poisoning among Indigenous Australians, 68% (1,514) were deaths of Indigenous males.

- the leading causes of death due to injury and poisoning were suicide (intentional self-harm) (38% of all injury and poisoning deaths or 847 deaths), transport accidents (19% or 417 deaths), accidental poisoning (18% or 413 deaths), assault (7.8% or 174 deaths) and falls (4.5% or 101 deaths). Suicide and transport accidents combined accounted for 56% of all deaths due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians (Table D1.23.10).

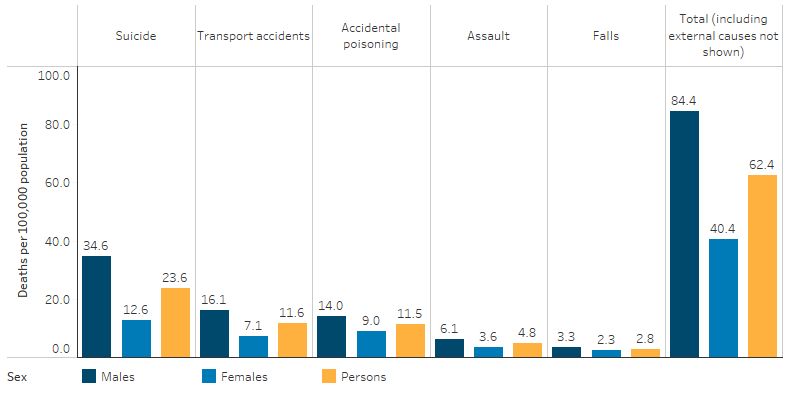

- the rate of death due to injury and poisoning was 62 deaths per 100,000 population, with a rate 2.1 times as high for Indigenous males as females (84 compared with 40 per 100,000) (Table D1.23.1, Figure 1.03.1). This was true for most leading causes, except falls where the rates were similar between males and females. The relative difference was highest for deaths due to suicide, with the rate for Indigenous males 2.7 times that of Indigenous females (35 and 13 per 100,000, respectively). This was followed by accidental drowning, with the rate for Indigenous males 2.5 times the rate for Indigenous females (2.7 and 1.1 per 100,000, respectively).

- the death rate due to injury and poisoning was highest in Western Australia (96 per 100,000) and lowest in New South Wales (47 per 100,000) (Table D1.23.2).

- the rate of death due to injury and poisoning in Remote and very remote areas was 1.7 times the rate in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner and Outer regional areas combined) (90 and 52 per 100,000, respectively) (Table D1.23.30).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians died from injury and poisoning at 2.0 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.23.1).

In 2015–2019, injury and poisoning was the leading cause of death for Indigenous Australians aged between 5 and 44 (Table D1.23.3). For those aged 5–14, the leading cause of injury and poisoning death was transport accidents (33% of all injury and poisoning deaths). For those aged between 15 and 44, the leading cause of injury and poisoning deaths was suicide (48% of injury and poisoning deaths). For Indigenous youths aged 15–19, about 69% of all injury and poisoning deaths were due to suicide (Table D1.23.11).

For Indigenous children aged 1–4, injury and poisoning accounted for almost half (47%) of all deaths (Table D1.23.3). The most common causes of death due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous children aged 0–4 was accidental drowning (35% of injury deaths) (Table D1.23.11).

Figure 1.03.1 Death rates for injury and poisoning (external causes) among Indigenous Australians, by external cause and sex, 2015–2019

Source: Table D1.03.1 AIHW National Mortality Database.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, across leading causes, for Indigenous Australians the rate of death due to:

- suicide was twice as high as for non-Indigenous Australians

- transport accidents was 2.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians

- accidental poisoning was 2.6 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians

- assault was 6.3 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians. This was the largest relative difference in rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.23.10).

Over the decade 2010 to 2019, and based on age-standardised rates, the death rate due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians increased by 14%. The rate for non-Indigenous Australians also increased (by 8%), with no significant change in the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.23.19).

Hospitalisation for injury and poisoning

Injury is one of the major causes of hospitalisation. Only a small proportion of all incidents of injury result in admission to a hospital. For each hospital admission, many more cases present to hospital emergency departments but are not admitted, or are seen by a general practitioner. A larger number of generally minor injuries do not receive any medical treatment.

From July 2017 to June 2019, there were 73,641 hospitalisations due to injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians – rate of 44 per 1,000 population (Table D1.02.5).

Excluding care involving dialysis, injury and poisoning was the leading cause of hospitalisation based on principal diagnosis for Indigenous Australians (12% of hospitalisations excluding dialysis, or 6.8% of all hospitalisations).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 1.8 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for injury and poisoning (Table D1.03.3).

Age and sex

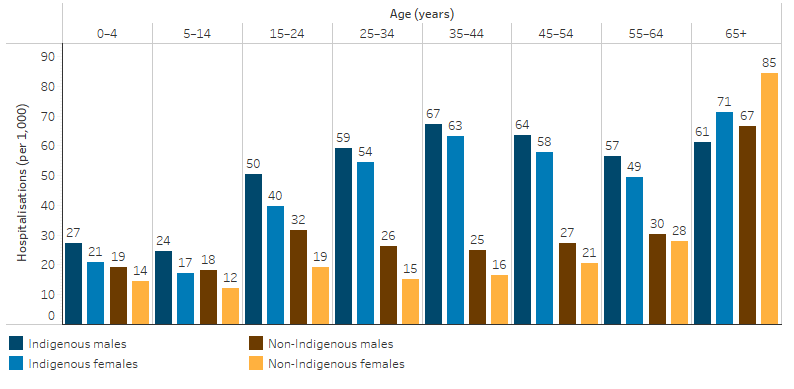

For Indigenous Australians aged 35–44, the hospitalisation rate for injury and poisoning was 65 per 1,000, 3.2 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (21 per 1,000), the highest relative difference across age groups. For both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning were highest for those aged over 65, reflecting the higher number of falls among older people (Table D1.03.2, Figure 1.03.2).

Figure 1.03.2: Age-specific hospitalisation rates for a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, by Indigenous status and sex, Australia, July 2017 to June 2019

Source: Table D1.03.2. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

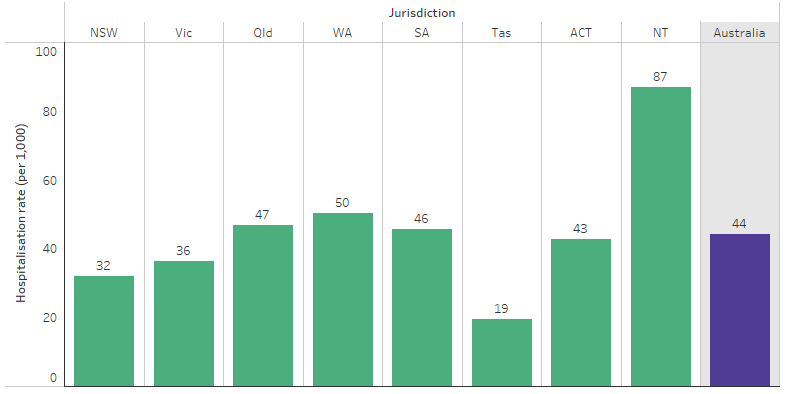

Jurisdiction and remoteness

Looking at rates of injury and poisoning by state and territory, for Indigenous Australians, the rate was lowest for those living in Tasmania (19 per 1,000 population), and highest for those living in the Northern Territory (87 per 1,000), followed by Western Australia (50 per 1,000 population) (Table D1.03.3, Figure 1.03.3).

Figure 1.03.3: Hospitalisation rates for Indigenous Australians for a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, by jurisdiction, Australia, July 2017 to June 2019

Source: Table D1.03.3. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

After adjusting for differences in age structure, hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning were higher for Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians in all jurisdictions except Tasmania (Table D1.03.3). The largest difference was for those living in the Northern Territory and Western Australia – rates for Indigenous Australians living in those jurisdictions were 2.2 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians.

The hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning were higher for Indigenous Australians living in Remote and Very remote areas (76 and 70 per 1,000 population, respectively), than in non-remote areas (36 per 1,000 in Major cities, 34 per 1,000 in Inner regional areas, and 45 per 1,000 in Outer regional areas) (34 per 1,000, respectively) (Table D1.03.4).

External cause of Injury hospitalisation

For Indigenous males, falls were the leading cause of hospitalisation due to injury and poisoning (21%) followed by assault (16%). For Indigenous females, assault was the leading cause (22%), followed by falls (21%) (Table D1.03.7, Figure 1.03.3). For Indigenous females, rates of non-fatal hospitalisation for family violence-related assaults were 31 times the rate for non-Indigenous females (see also measure 2.10 Community safety) (Table D2.10.35). Hospitalisations for intentional self-harm represented 11% of hospitalisations of Indigenous females, nearly twice as high as for Indigenous males (5.5%) (Table D1.03.7, Figure 1.03.4).

Figure 1.03.4: First reported external causes for hospitalisations for a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning and other consequences for Indigenous Australians, by sex, July 2017 to June 2019

Source: Table D1.03.7. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Rates of hospitalisation due to assault for Indigenous Australians were highest in Remote areas (24 per 1,000) and Very remote areas (25 per 1,000), and lowest in Inner regional areas (3.0 per 1,000) (Table D2.10.6; see measure 2.10 Community safety). Indigenous Australians are also more likely to be subjected to subsequent admissions into hospital as a result of interpersonal violence than Other Australians (people who have declared they are non‑Indigenous and those whose Indigenous status is unknown) (Berry et al. 2009; Meuleners et al. 2008).

For Indigenous Australians living in non-remote areas, falls were the most reported external cause of hospitalisation for both same-day and overnight hospitalisations (3.1 and 5.3 per 1,000). In remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined), the leading cause was assault (11 and 13 per 1,000, respectively) (Table D1.03.17).

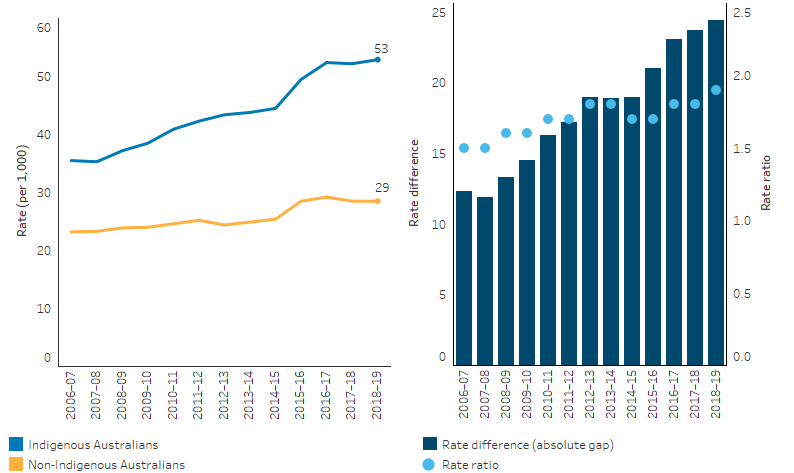

Changes over time in hospitalisations

Between 2006–07 and 2018–19, hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians increased by 49% in the six jurisdictions combined with Indigenous identification data of adequate quality (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory). Looking at the decade from 2009–10 and 2018–19, hospitalisation rates for injury and poisoning for Indigenous Australians increased by 34% in the 6 jurisdictions combined (Table 1.03.5).

Note that some of the changes over time are affected by changes in coding practices. In particular:

- From July 2015, a new coding rule was introduced to the ICD-10-AM relating to coding of care for rehabilitation (ACS 2104 Rehabilitation). From July 2015, where patients were admitted to hospital specifically for rehabilitation, the principal diagnosis should be assigned to the condition which led to the need for rehabilitation, and Z50.9 assigned only as an additional diagnosis (prior to this, Z50.9 could be assigned as the principal diagnosis). This resulted in an unusually high increase in the number (and rate) of hospitalisations due to injury and poisoning between 2014–15 and 2015–16.

- In New South Wales, from 2017–18, episodes of care delivered entirely within a designated emergency department or urgent care centre are no longer categorised as an admission regardless of the amount of time spent in hospital. This resulted in a reduction the number of admissions due to injury and poisoning in New South Wales (and nationally) between 2016–17 and 2017–18.

Based on age-standardised rates, injury and poisoning hospitalisations increased by more for Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians over the decade to 2018–19 (40% compared with 23%), resulting in a widening of the gap (the difference in the rates increased from 15 per 1,000 in 2009–10 to 24 per 1,000 in 2018–19) (Table D1.03.5, Figure 1.03.6).

Figure 1.03.5: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Notes:

1. Two separate changes in coding practices contributed to the increase in the rate of hospitalisations between 2014–15 and 2015–16, and to a decrease between 2016–17 and 2017–18. See footnotes to Table D1.03.5 for details.

2. Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D1.03.5. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

General Practitioner reported data

According to the Bettering the Evaluation and Care of Health (2015–16) survey, injuries accounted for 4.5% of all problems managed by general practitioners (GP) for Indigenous patients. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, the rate of injuries managed per 1,000 GP encounters was similar for Indigenous and Other Australian patients (70 and 66 per 1,000 encounters respectively). Injuries most commonly managed by a GP for Indigenous Australians were musculoskeletal injuries (38 per 1,000 encounters) and skin injuries (26 per 1,000 encounters). Although assault/harmful event accounted for only 0.2% of all problems managed by GPs for Indigenous patients, the rate was 4.4 times as high as for Other Australian patients (2.5 and 0.6 per 1,000 encounters respectively) (Table D1.03.8).

Findings from ABS survey data

Based on the 2012–13 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 19% of Indigenous Australians had experienced injuries in the 4 weeks prior to the survey, with falls (45%) and hitting or being hit by something (19%) being the most common events causing injury. The main types of injuries were open wounds (35%) and bruising (28%). Action was taken by 46% of those injured and of those who were treated, 11% of those aged 15 and over were injured while under the influence of alcohol or other drugs. Of those with a long-term health condition, 27% reported that it was as a result of injury or an accident (Table D1.03.9). After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over experienced stress due to a serious accident at a rate 1.8 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians (6.7% and 3.8%, respectively) (ABS 2013).

Research and evaluation findings

Mortality, hospital and survey data can be unpacked further to understand factors and characteristics associated with the high burden of injury for Indigenous Australians. Finer disaggregation by age, sex, remoteness, and specific causes by the research community can shed light on where targeted interventions could be effective such as around social and emotional wellbeing, road safety, alcohol use, and violence.

Across the period 2015–2019, injury and poisoning (2,240 or 15% of all deaths) was the third broad leading cause of death for Indigenous Australians. Of deaths due to injury and poisoning, the 3 most frequent external causes of death for Indigenous Australians were suicide (38% of all injury deaths), transport accidents (19%) and unintentional poisoning by/exposure to noxious substances (18%) (see measure 1.23 Leading causes of mortality). The relative difference between the rates of deaths due to injury and poisoning for males and females was high, with the rate for Indigenous males 2.1 times that of Indigenous females (Table D1.23.10). Across the period 2011–12 to 2015–16, for both sexes, 8 in 10 Indigenous suicide deaths occurred between the ages of 15 and 44. For children aged 5–14, suicide rates for Indigenous boys and girls were 9 and 7 times as high (respectively) as for non-Indigenous boys and girls (AIHW 2020).

Indigenous Australians were 3.1 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to experience a fatal injury as a car occupant. In general, rates of fatal and serious land transport injury increase with remoteness (Henley & Harrison 2019). A number of factors contribute to the higher rates of injury in remote areas, where higher proportions of Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians live. Risk factors include greater distances travelled, higher speed limits, poor condition of roads, poor availability of transport services, greater diversity in vehicle condition and delay in accessing medical treatment (Thomson et al. 2009). Alcohol and substance use is a known factor in suicide (Robinson et al. 2011), transport accidents (Fitts et al. 2017; West R. et al. 2014b) as well as assault (Mitchell 2011) (see measures 2.16 Risky alcohol consumption and 2.17 Drug and other substance use including inhalants).

Indigenous Australian children are disproportionately affected with higher mortality and hospitalisation rates for some injury types. Evidence shows that family and community wellbeing were protective against child injury, with programs and services to support caregivers’ wellbeing leading to improvement in injury prevention for the child (Thurber et al. 2018) (see measure 1.13 Community functioning).

In 2018, injuries were the leading cause of fatal burden for Indigenous children aged 1–14 and Indigenous young people aged 15–24 (47% and 80%, respectively) (AIHW 2022).

Over the period 2015–2019, among Indigenous children aged 1–4, almost half of all deaths were due to injury and poisoning, including transport accidents and other accidents and injuries such as accidental drowning (Table D1.20.14) (see measure 1.20 Infant and child mortality).

A study using linked hospital data to construct cohorts of children born in New South Wales hospitals between 2003–07 and 2008–12 found that, in both cohorts, falls were the leading cause of injury followed by burns and poisoning for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children. While rates of injury in Indigenous children caused by burns, poisoning and traffic were lower in the later cohort compared with the early cohort, overall rates of hospitalisation caused by unintentional injury remained similar in both cohorts. Injury hospitalisation inequalities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous children remained similar across the period, with Indigenous children almost twice as likely to suffer unintentional injury as non-Indigenous children (Möller et al. 2019).

For young Indigenous Australians aged 10–24, about two-third of the injury-related hospitalisations during 2011–2013 were unintentional while the remaining causes were intentional including assault and self-harm. Assault was the most common injury-related hospitalisation for Indigenous adolescents aged between 15–19 and 20–24 (708 and 1,420 per 100,000, respectively). It was followed by intentional self-harm (423 and 473 per 100,000, respectively), with the incidence in Indigenous adolescents almost twice that of non-Indigenous adolescents (Azzopardi et al. 2018).

A long-term study in the Northern Territory examined hospitalisations and deaths related to injury from 1997–2011. Across the period, the study found that hospitalisation rates in the Northern Territory were higher than the national average (70% higher in 2011). The Northern Territory Indigenous injury death rate was twice the Northern Territory non-Indigenous rate and 70% higher than the national Indigenous rate. Reasons for this are complex, but alcohol is considered to be a contributing factor, particularly in hospitalisations for assault (Foley et al. 2015).

Implications

Intentional and unintentional injuries are preventable. Effective injury prevention measures should identify causes and either remove them, or reduce exposure to them. A National Injury Prevention Strategy 2020–2030 is currently being developed and will outline the best ways to reduce the rate of injury across age groups (DoH 2020). The Strategy identifies Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as a priority population, along with people living in rural and remote areas, and people experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage.

The existing data can provide insight into some of the factors that are associated with the high rates of injury for Indigenous Australians such as age, sex and remoteness to assist in targeting prevention activities. This measure on injury and poisoning covers a broad range of policy, service delivery and health promotion issues such as suicide and self-harm, transport safety, accidental injury and community safety. Further research such as geospatial analysis, and data linkage of mortality, hospital and other health services data could provide new insights, and could highlight other contextual issues (including protective factors) specific to Indigenous Australians to inform targeted interventions.

Addressing the high rates of suicide among Indigenous Australians is an urgent priority receiving significant policy attention in recent years. Understanding the differences in the characteristics of suicide deaths and hospitalisation for self-harm among Indigenous Australian males and females compared to those for non-Indigenous Australian males and females is important for helping to target strategies that can prevent future suicide and self-harm.

Policy responses aimed at addressing injury prevention need to be evidence based, multi-dimensional, relevant and address systemic issues that reduce people's capacity to make health-enhancing choices (Anderson 2008; Berger et al. 2009; Berry et al. 2009). Alcohol and substance use have been found to be a factor in suicide and transport accidents as well as assault (Fitts et al. 2017; Mitchell 2011; Robinson et al. 2011; West C. et al. 2014a). Strategies to prevent injuries should address road safety, child car safety and alcohol abuse. In keeping with the holistic conceptualisation of health and wellbeing for Indigenous Australians, safety promotion and injury prevention activities should also address the social, cultural and geographic context in which Indigenous Australians live.

Over the past decade, efforts to reduce Indigenous child (0–4 years) mortality have focussed on reducing risk factors and improving maternal and child health particularly during pregnancy and infancy, as these factors have the most potential to affect child death rates. More research is needed to understand why improvements in health risk factors are not translating into stronger improvements in Indigenous child (0–4) death rates (PM&C 2020). The high proportion of injury related deaths among Indigenous children (1–4) may warrant more attention. Although these represent a much smaller contribution to the overall number of deaths among Indigenous children (0–4) they also represent an opportunity to address risks that are largely preventable such as transport accidents and drowning.

The Policy Context is at Policies and Strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2013. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: First Results Australia 2012–13. cat. no. 4727.0.55.001. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Hospitalised injury among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, 2011–12 to 2015–16. Injury research and statistics series no. 118. Cat. no. INJCAT 198. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2020. Indigenous injury deaths 2011–12 to 2015–16. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

- Anderson I 2008. An analysis of national health strategies addressing Indigenous injury: consistencies and gaps. Injury 39:S55-S60.

- Azzopardi P, Sawyer S, Carlin J, Degenhardt L, Brown N, Brown A et al. 2018. Health and wellbeing of Indigenous adolescents in Australia: a systematic synthesis of population data. The Lancet 391:766-82.

- Berger LR, Wallace LD & Bill NM 2009. Injuries and injury prevention among indigenous children and young people. Pediatric Clinics 56:1519-37.

- Berry JG, Harrison JE & Ryan P 2009. Hospital admissions of indigenous and non-indigenous Australians due to interpersonal violence, July 1999 to June 2004. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33:215-22.

- DoH (Australian Government Department of Health and Aged care) 2020. National Injury Prevention Strategy 2020-2030.

- Fitts MS, Palk GR, Lennon AJ & Clough AR 2017. The characteristics of young Indigenous drink drivers in Queensland, Australia. Traffic Injury Prevention 18:237-43.

- Foley M, Zhao Y, You J & Skov S 2015. Injuries in the Northern Territory 1997-2011. Darwin Department of Health - Northern Territory.

- Haysom L, Indig D, Moore E & Gaskin C 2014. Intellectual disability in young people in custody in New South Wales, Australia–prevalence and markers. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 58:1004-14.

- Henley G & Harrison J 2019. Injury of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people due to transport, 2010–11 to 2014–15. Canberra: AIHW.

- MacRae A, Thomson N, Potter C & Anomie 2013. Review of injury among Indigenous peoples. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

- Meuleners LB, Hendrie D & Lee AH 2008. Hospitalisations due to interpersonal violence: a population-based study in Western Australia. The Medical Journal of Australia 188:572-5.

- Mitchell L 2011. Domestic violence in Australia: an overview of the issues. Canberra: Department of Parliamentary Services.

- Möller H, Falster K, Ivers R, Falster M, Clapham K & Jorm L 2017. Closing the Aboriginal child injury gap: targets for injury prevention. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 41:8-14.

- Möller H, Ivers R, Clapham K & Jorm L 2019. Are we closing the Aboriginal child injury gap? A cohort study. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 43:15-7.

- PM&C (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet) 2020. Closing the Gap Report 2020.

- Robinson G, Silburn S & Leckning B 2011. Suicide of Children and Youth in the NT 2006-2010: Public Release Report for the Child Deaths Review and Prevention Committee. Darwin: Menzies SHR.

- Stephens A, Cullen J, Massey L & Bohanna I 2014. Will the National Disability Insurance Scheme Improve the Lives of those Most in Need? Effective Service Delivery for People with Acquired Brain Injury and other Disabilities in Remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities. Australian Journal of Public Administration 73:260-70.

- Thomson N, Krom I & Ride K 2009. Summary of Road Safety Among Indigenous Peoples. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

- Thurber K, Burgess L, Falster K, Banks E, Möller H, Ivers R et al. 2018. Relation of child, caregiver, and environmental characteristics to childhood injury in an urban Aboriginal cohort in New South Wales, Australia. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 42:157-65.

- West C, Usher K & Clough AR 2014a. Study protocol - resilience in individuals and families coping with the impacts of alcohol related injuries in remote indigenous communities: a mixed method study. BMC Public Health 14.

- West R, Usher K, Foster K & Stewart L 2014b. Academic staff perceptions of factors underlying program completion by Australian Indigenous nursing students. The Qualitative Report 19:1.