Key messages

- In 2018–19, 16% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 15 and over reported they were a victim of either physical or threatened physical harm in the preceding 12 months.

- The rate of hospitalisation of Indigenous Australians due to assault was highest in Remote and Very remote areas (2,353 and 2,458 per 100,000 population, respectively) and lowest in Inner regional areas (297 per 100,000 population) between July 2017 and June 2019.

- Indigenous females were 27 times as likely to be hospitalised for assault as non-Indigenous females between July 2017 and June 2019. The difference between the two populations was largest in Remote areas where Indigenous females were 51 times as likely to be hospitalised due to assault as non-Indigenous females living in the same region.

- Between July 2017 and June 2019, the rates of non-fatal family violence-related hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians were 30 times that for non-Indigenous Australians.

- For hospitalisations of Indigenous females due to assault where information about the perpetrator was recorded, the perpetrator was a domestic partner in 62.3% (8,525) of cases and another family member or parent in 23.5% (3,225) of cases.

- In 2018–19, of reported experiences of physical harm among Indigenous Australians, offenders were believed to be under the influence of alcohol or other substances in 74% of these incidents. This was more likely to be the case in remote areas (77%) than non-remote areas (74%).

- Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, the rate of hospitalisation from assault increased from 814 to 914 hospitalisations per 100,000 population for Indigenous females. For Indigenous males over the same period, there was a reduction in the hospitalisation rate — 802 to 760 per 100,000 population.

- Over the last decade to 2019, the age-standardised rate of deaths due to homicide for Indigenous Australians declined by 37%, and the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians narrowed by 39%.

- Some of factors believed to contribute to high rates of violence within Indigenous communities include loss of land and traditional culture; breakdown of community kinship systems; entrenched poverty; racism; alcohol and drug abuse; and the effects of institutionalisation and removal policies.

- Research has shown that experiencing family violence can affect a person’s education, employment, economic security, and housing outcomes.

- Research shows that aspects of successful family violence programs include community involvement in service planning; engagement and relationship building; consideration of cultural factors; integrated service delivery; planning for long-term sustainability; and having a holistic focus with flexible, trauma-informed approaches.

- Actions to curb the drivers of violence experienced by Indigenous Australians could include addressing intergenerational trauma through healings; connection to culture and cultural identity; support for families; specific initiatives for women and girls; targeted initiatives for men and boys; challenging the condoning of violence; equality in law and access to justice; and reducing the rate of incarceration

Why is it important?

Safe communities, where people feel secure and protected from harm within their home, workplace and community, are important for physical and social and emotional wellbeing (AIHW 2019a) . When a person feels safe, they are enabled to live a better quality and healthier life, are more likely to engage in the community, and the community as a whole faces a lower incidence of injuries and violence.

Many factors can influence community safety and wellbeing for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (AIHW 2019a). This includes social determinants such as access to suitable housing, income, education and employment opportunities. Poverty, and a lack of educational and employment opportunities, can diminish hope and aspiration, leading to substance abuse, poor mental health, and an increased likelihood of involvement in crime (Australian Human Rights Commission 2020) . Cultural determinants are also a factor and some positive influences include being connected to Country, kin, land, family and spirit; having strong and positive social networks; healing from trauma; empowerment, self-determination and having strong leadership in both family and community.

However, Indigenous Australians can face harm from structural, institutional and interpersonal factors. Experiencing threats and acts of violence, living in an environment where personal safety is at risk and facing social settings where violence is common can have negative health effects on victims of violence, including women and children and their families (AIHW 2018; Coles et al. 2015; Loxton et al. 2019) . Experiences of violence can occur both in the community and in a home environment, and violence may originate from strangers, family and kinship relations (AIHW 2018; Our Watch 2018b).

Indigenous Australians are generally over-represented as both perpetrators and victims of violent crimes, and tend to experience violence in the community and family violence at higher rates than non-Indigenous Australians (Bartels 2010; Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2013) . Non-Indigenous Australians are also perpetrators of violence against Indigenous Australians. Indigenous Australians are also over-represented in Australia’s child protection, youth and adult justice systems (see measures 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system and 2.12 Child protection).

In Australia, homicide and violence accounted for 10% of the burden of disease due to injuries in 2018, with 61% of this burden experienced by Indigenous males and 39% experienced by Indigenous females. Exploratory analysis from the Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 suggested that while intimate partner violence was by far the main contributor to the homicide and violence burden for females, the burden for males was spread across family members, intimate partners and acquaintances (AIHW 2022: Box 5.3 and Table 5.4). Family violence is a major reason for seeking assistance from homelessness services (see measure 2.01 Housing) and can also have implications for child protection (see measure 2.12 Child protection).

Indigenous Australians have experienced violence in the context of colonisation, intergenerational trauma, discrimination, and cultural dispossession (Day et al. 2013) Our Watch 2018b). The Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices) Report (2020) also highlights that intersectional discrimination, which is a combination of race, gender, culture and other discrimination, is a major driver of violence against Indigenous women and girls (Australian Human Rights Commission 2020). This has resulted in social, economic, physical, psychological and emotional effects for Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2018; Coles et al. 2015; Loxton et al. 2019) (AIHW 2018; Coles et al. 2015; Loxton et al. 2019; Our Watch 2018b). This environment has fostered a climate of lateral violence for some communities.

‘Lateral violence’ describes the way people (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) in positions of powerlessness covertly or overtly direct their dissatisfaction inward towards themselves, each other and those less powerful than themselves. Lateral violence is a product of complex historical and social dynamics that is not limited to physical violence but can also include social, emotional, psychological, economic and spiritual forms of violence by individuals and groups (Australian Human Rights Commission 2011). For Indigenous Australians, the roots of this are found in colonisation, control, oppression, intergenerational trauma and experiences of racism (Korff 2015).

The majority of Indigenous Australians do not commit violence or criminal behaviour, however they are disproportionally on the receiving end of violence. Improving the level of safety in all communities is dependent on addressing entrenched inequality and disadvantage and the multiple factors that give rise to violent and criminal behaviour. This includes addressing the social and cultural determinants. Australian governments have a pivotal role to play working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to address these factors.

In July 2020, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) identified the importance of ensuring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families and households are safe. The National Agreement identified the following target to measure family and household safety:

- Target 13—By 2031, the rate of all forms of family violence and abuse against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children is reduced at least by 50%, as progress towards zero.

There are several supporting indicators under this target such as hospitalisation rates for family violence related assault and homicide rates. For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

Data findings

Reported experience of violence

In the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), more than 1 in 7 Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over (16%; 76,900) reported they experienced physical and/or threatened physical harm in the preceding 12 months. The proportion for Indigenous Australians who were a victim of physical or threatened violence was similar in surveys conducted in 2002, 2008 and 2014–15 (23%). While these outcomes are similar, they are not directly comparable (Table D2.10.21).

Experiencing actual physical harm in the last 12 months was reported by 6.3% of Indigenous Australians aged over 15 in 2018–19 (around 30,900 people). Of these victims, 74% (around 22,300) reported that they believed their offender was under the influence of alcohol or other substances during the most recent incident. Alcohol or other substances were more likely to be a factor in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined) (77%) than non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner and Outer regional areas combined) (74%) (Table D2.10.19).

Among the Indigenous Australian population in 2018–19, the reported rates for experience of physical or threatened physical harm were slightly higher for males (17%; 39,900) than for females (14%; 36,700) (Table D2.10.22). Indigenous females reported actual physical harm at a similar rate to Indigenous males (6.2% or 15,040, compared with 6.4% or 16,005) (Table D2.10.19).

Of Indigenous Australian victims, females were just as likely as males to report that they knew the offender responsible for their most recent physical harm at 95% (15,100 people) compared with 94% (13,800). For females who knew the offender, 52% reported that it was a current or previous partner, and 31% reported that it was a friend or family member (Table D2.10.19).

Of Indigenous Australians who experienced physical harm in the last 12 months (30,900 people), 44% (13,500) reported the most recent incident to police. Indigenous females were twice as likely as males to have reported the most recent incident (60% compared with 29%). Of those who did not report the most recent incident of physical harm to police, reasons for not reporting included believing it was a personal matter (34%), believing there was nothing police could do or that they would be unwilling to do something (17%), or thought it was too trivial/unimportant (15%) (Table D2.10.42).

Formal and informal support services may be used by individuals who have experienced physical harm. Of Indigenous Australians who experienced physical harm in the last 12 months (30,900 people), over half (51%) sought help from support services for the most recent incident of physical harm. Indigenous females were more likely than males to have sought help (61% compared with 39%). Among those who sought help, 41% sought informal support (friend or family member/work colleague or boss/church), 40% sought help from the police, and 39% sought help from GPs/Aboriginal Medical Services or Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Services (Table D2.10.41).

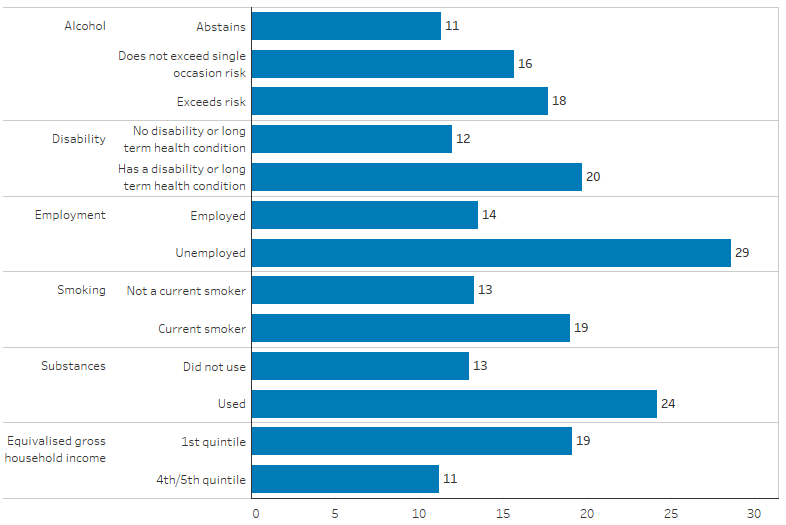

The NATSIHS also found that Indigenous Australians were more likely to report experiencing being a victim of physical or threatened physical harm if they were:

- someone with a disability or long-term health condition (20% compared with 12% for someone with no disability)

- unemployed (29% compared with 14% for those employed)

- a current smoker (19% compared with 13% for non-smokers)

- a substance user in last 12 months (24% compared with 13% for those who did not use substances) (Table D2.10.1).

Indigenous Australians were also more likely to report being a victim if they were in the lowest (1st) quintile of equivalised gross household income (19%) compared with if they were in either of the two highest (4th/5th) quintiles (11%) (Table D2.10.1, Figure 2.10.1).

Figure 2.10.1: Proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who reported experiencing physical or threatened physical harm in the previous 12 months, by selected health and population characteristics, 2018–19

Source: Table D2.10.1. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

In the 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS), Indigenous females aged 15 and over were less likely to feel safe walking alone in their local area after dark than Indigenous males (51% compared with 83%) and were less likely to feel safe alone at home after dark (79% compared with 95%) (Table D2.10.2).

Questions about neighbourhood and community problems in the NATSISS found that Indigenous Australians living in remote areas were more likely to report being aware of neighbourhood and community problems than those living in non-remote areas. Those in remote areas were more likely to report awareness of problems involving: youths, such as gangs or lack of activity (51% compared with 26%); alcohol (65% compared with 31%); family violence (48% compared with 19%); and assault (46% compared 14%) (Table D2.10.3).

Hospitalisations due to assault

In this section, information is presented on hospitalisations due to assault – defined as hospitalisations where the principal diagnosis was injury and poisoning, and where the first reported ‘external cause’ was assault. External cause is defined as the environmental event, circumstance, or condition that is regarded as the cause of injury, poisoning and other adverse effect.

Between July 2017 to June 2019, there were 14,061 hospitalisations due to assault (1.3% of total hospitalisations including dialysis) among Indigenous Australians, at a rate of 8.5 per 1,000 population. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 14 times as likely to be hospitalised for assault as non-Indigenous Australians (Table D2.10.4).

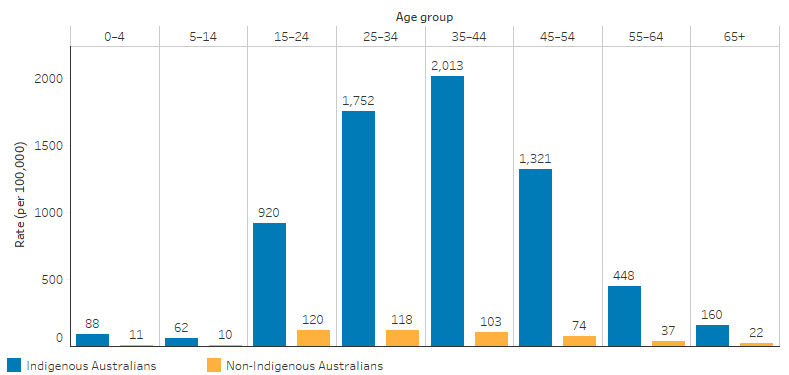

Indigenous Australians aged 35–44 had the highest rates of hospitalisation due to assault (2,013 hospitalisations per 100,000 population, compared with 103 per 100,000 for non-Indigenous Australians) (Table D2.10.4, Figure 2.10.2).

Figure 2.10.2: Rates of hospitalisation due to assault, by Indigenous status and age, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

Source: Table D2.10.4. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

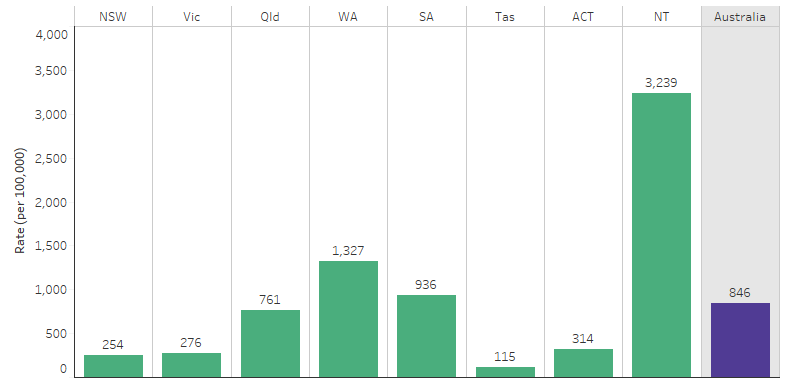

By state and territory, the rates of hospitalisation of Indigenous Australians due to assault were lowest in Tasmania (115 per 100,000 population) and highest in the Northern Territory (3,239 per 100,000 population) (Table D2.10.5, Figure 2.10.3).

Figure 2.10.3: Hospitalisation rates of Indigenous Australians due to assault, by state and territory, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

Source: Table D2.10.5. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

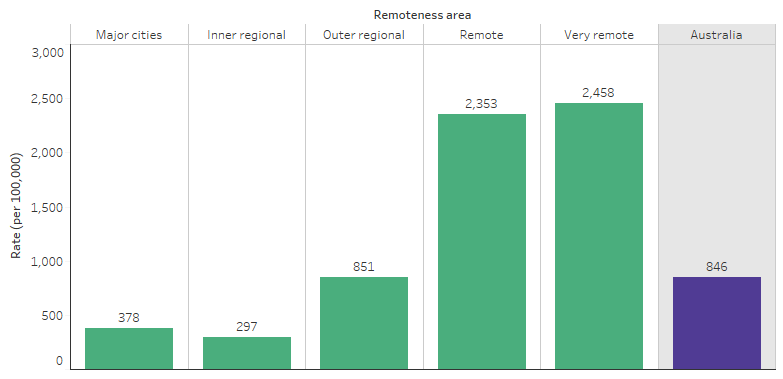

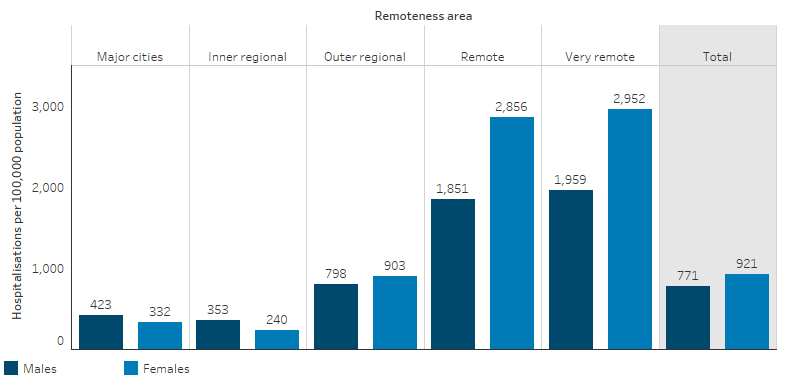

By remoteness, the rates of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians due to assault were lowest in Inner regional areas (334 per 100,000 population) and highest in Remote and Very remote areas (2,353 and 2,458 per 100,000 population, respectively). Rates of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians due to assault in Remote and Very remote areas were 23 and 21 times as high as for non-Indigenous Australians living in the same regions, respectively (Table D2.10.6).

Figure 2.10.4: Hospitalisation rates of Indigenous Australians due to assault, by remoteness, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

Source: Table D2.10.6. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Overall, females made up 54% of hospitalisations among Indigenous Australians due to assault, compared with 28% among non-Indigenous Australians from July 2017 to June 2019 (Table D2.10.5).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous females were 27 times as likely as non‑Indigenous females to have been hospitalised due to assault nationally. Across remoteness areas, the difference in rates was highest for Indigenous females in Remote areas, where Indigenous females were 51 times as likely to be hospitalised for assault than non-Indigenous females, followed by Very remote areas (36 times as likely). Indigenous females living in the Northern Territory were 50 times as likely to be hospitalised due to assault compared with non-Indigenous females in the same jurisdiction.

Indigenous males were 9 times as likely as non-Indigenous males to be hospitalised for assault. Across remoteness areas, the highest difference in rates between Indigenous and non-Indigenous males were for those living in Remote and Very remote areas, with rates 13 and 14 times as high for Indigenous males as for non-Indigenous males, respectively. In Western Australia, Indigenous males were 13 times as likely as non-Indigenous males to be hospitalised due to assault (Table D2.10.5, Table D2.10.6).

The rates of hospitalisation due to assault were lower for Indigenous females than for Indigenous males in Major cities (332 compared with 423 per 100,000 population, respectively) and Inner regional areas (240 compared with 352 per 100,000 population, respectively). In contrast, Indigenous females were more likely than Indigenous males to be hospitalised due to assault in Remote areas (2,856 compared with 1,851 per 100,000 population, respectively) and in Very remote areas (2,952 compared with 1,959 per 100,000 population, respectively) (Table D2.10.6, Figure 2.10.5).

Figure 2.10.5: Hospitalisation rates of Indigenous Australians due to assault, by remoteness and sex, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

Source: Table D2.10.6. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

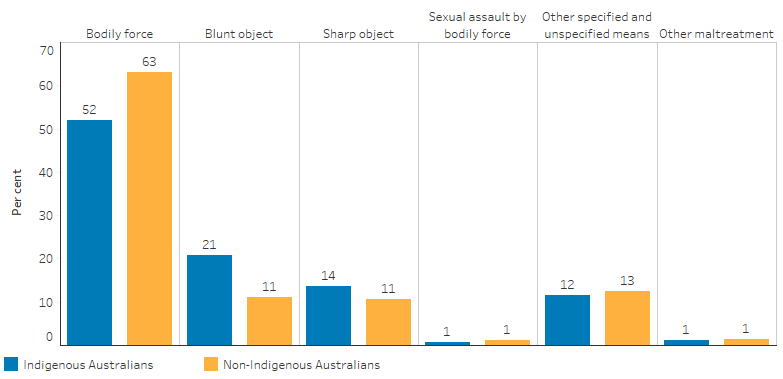

Injury circumstances

The most common external causes of injury for Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians hospitalised due to assault between July 2017 and June 2019 were assault by bodily force (52% compared with 63%), assault by blunt object (21% compared with 11%), and assault by sharp object (14% compared with 11%) (Table D2.10.13, Figure 2.10.6).

Figure 2.10.6: Proportion of hospitalisations due to assault, by most common cause of injury and Indigenous status, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

Source: Tables D2.10.13. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

The location of the assault was recorded for 29% of hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians (9,436) and 52% of hospitalisations for non-Indigenous Australians (40,275) between July 2014 and June 2019. When recorded, the home was the most common location for the assault for both Indigenous (58%; 5,476 hospitalisations) and non-Indigenous Australians (46%; 18,503 hospitalisations) (Table D2.10.15).

For hospitalisations due to assault among Indigenous females nationally, 7 in 10 (69%; 3,812) were due to assaults in the home, 9% for assaults on a street or highway (494) and 6% for assaults in a trade/service area (316). For Indigenous males, the most common location was also the home (42%; 1,664 hospitalisations), followed by trade/service area (15.4%; 605) and street/highway (14.7%; 576) (Table D2.10.15).

For Indigenous Australians living in non-remote areas, 59% (3,443) of hospitalisations due to assault were for due to assaults that occurred in the home; this proportion was similar in remote areas 57% (1,928). For Indigenous females living in non-remote areas, 76% (2,305) of hospitalisations for assault occurred at home compared with 61.6% (1,431) in remote areas. For Indigenous males, the proportion of hospitalisation for assaults that occurred at home was lower in non-remote areas (41.3%; 1,138) than remote areas (46.5%; 497) (Table D2.10.15).

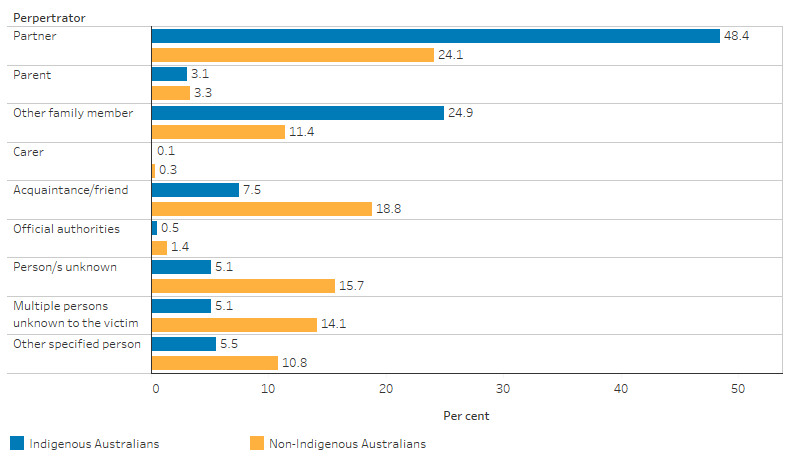

Family violence-related assaults

In data on hospitalisations due to assault from July 2014 to June 2019, the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim was specified for 63.4% of hospitalisations (20,627 of 32,529 total assault hospitalisations) (Table D2.10.16).

Where the relationship was specified, the victim knew the perpetrator in more than 8 out of 10 cases (84%; 17,303 hospitalisations). In about three quarters of specified cases (76%; 15,738) the victim was a family member; in 48% (9,979) of specified cases the perpetrator was a domestic partner; in a quarter of cases (25%; 5,126), it was another family member; and in 3.1% (633) of cases it was a parent. For non-Indigenous Australian victims, 6 out of 10 cases (58%) knew the perpetrator: a domestic partner in a quarter of all specified cases (24%) and another family member in another 11.4% of all cases (Table D2.10.16, Figure 2.10.7).

Figure 2.10.7: Proportion of assault hospitalisations, by the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim, by Indigenous status, July 2014 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault. Percentages calculated after excluding hospitalisations for assault where the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim was not specified.

Source: Table D2.10.16. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

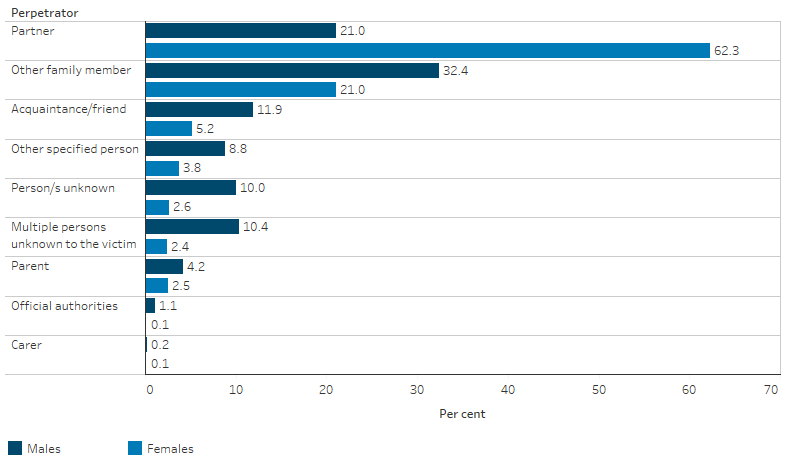

For hospitalisations due to assault where the perpetrator was specified, for Indigenous females the recorded perpetrator was a domestic partner in 62.3% (8,525) of cases, and another family member or parent in a quarter of cases (23.5%; 3,225). In comparison, for Indigenous males, a domestic partner was the recorded perpetrator in 21% of cases (1,454 hospitalisations) and another family member of parent in 36.6% of cases (2,534 hospitalisations) (Table D2.10.16, Figure 2.10.8).

Figure 2.10.8: Proportion of assault hospitalisations of Indigenous Australians, by the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim, by sex, July 2014 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault. Percentages calculated after excluding hospitalisations for assault where the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim was not specified.

Source: Table D2.10.16. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

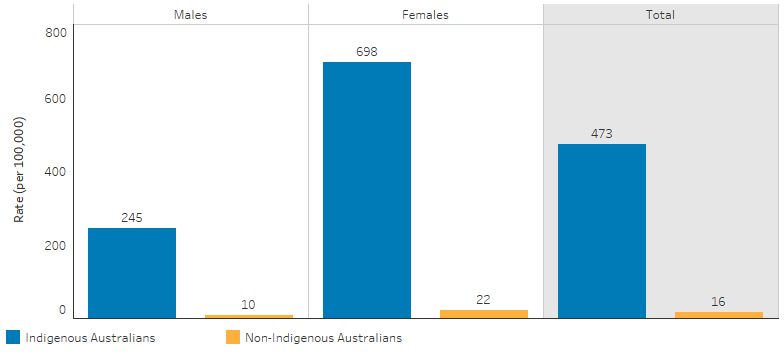

In this measure, ‘non-fatal hospitalisations for family-violence related assaults’ includes hospitalisations for assault where the perpetrator was recorded as a spouse/domestic partner, parent, or other family member and where the patient survived. The rate of non-fatal hospitalisations for family-violence related assaults for Indigenous Australians was 30 times that for non-Indigenous Australians, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations.

For Indigenous females, the rate of non-fatal hospitalisations for family violence-related assaults was 31 times the rate for non-Indigenous females, and for Indigenous males, it was 26 times the rate for non-Indigenous males (Figure 2.10.9). Across 10-year age groups for females, the Indigenous female population aged 35–44 had the highest rates of non-fatal hospitalisations for family violence-related assaults (1,523 per 100,000 population) (Table D2.10.35).

Figure 2.10.9: Age-standardised rate of non-fatal hospitalisations for family violence-related assaults, by sex and Indigenous status, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault, and where the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim was a spouse/domestic partner, parent, or other family member. Non-fatal refers to records where the mode of separation was not equal to 'died'.

Source: Table D2.10.35. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

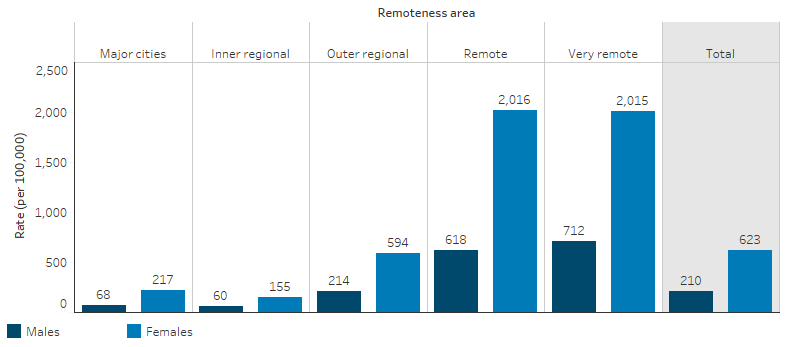

Indigenous Australians living in Remote and Very remote areas had the highest rates of non-fatal hospitalisation for family violence-related assaults (1,315 and 1,367 per 100,000 population respectively), compared with between 107 and 404 per 100,000 population across other non-remote areas (Table D2.10.37).

Rates of non-fatal hospitalisations for family-violence related assaults were higher for Indigenous females than for Indigenous males in all remoteness areas. The largest difference was for those in Remote areas, where the rate was 2,016 hospitalisations per 100,000 population for females, compared with 618 per 100,000 for Indigenous males (Table D2.10.37, Figure 2.10.10).

Figure 2.10.10: Rate of non-fatal hospitalisations for family violence-related assaults of Indigenous Australians, by remoteness and sex, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault, and where the relationship of the perpetrator to the victim was a spouse/domestic partner, parent, or other family member. Non-fatal refers to records where the mode of separation was not equal to 'died'.

Source: Table D2.10.37. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

By state and territory, the rates of non-fatal hospitalisation for family violence-related assaults were at least twice as high in the Northern Territory compared with any other state (1,902 per 100,000 population), followed by 666 per 100,000 in Western Australia (Table D2.10.36).

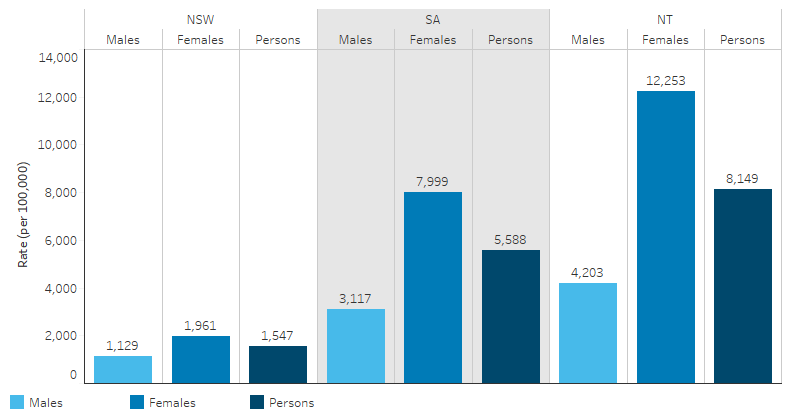

Police assault records

In 2021, in the three jurisdictions for which data were available, the number of recorded Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims of assault was:

- 6,379 in the Northern Territory (8,149 per 100,000 population)

- 4,512 in New South Wales (1,547 per 100,000 population)

- 2,600 in South Australia (5,588 per 100,000 population).

Across these states and territories, most Indigenous victims of assault were female: 74% in the Northern Territory (4,711 victims), 72% in South Australia (1,879), and 63% in New South Wales (2,865) (ABS 2022a) (Figure 2.10.11).

Figure 2.10.11: Rate of assault victims among Indigenous Australians, by jurisdiction and sex, 2021

Note: Caution should be used when comparing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander victims across states and territories and time periods, due to variations in the proportion of victims with unknown Indigenous status – in 2021, Indigenous status was ‘not stated’ for 29% of assault victims in New South Wales, compared with 7% in the Northern Territory and 3% in South Australia.

Source: AIHW analysis of ABS Recorded Crime – Victims collection (ABS 2022a) Table 24.

As a proportion of the total assault victims in each state and territory, Indigenous Australians accounted for:

- 70% of assault victims in the Northern Territory (in comparison, Indigenous Australians represented 31% of the total population in the Northern Territory),

- 14% of assault victims in South Australia (Indigenous Australians represented 2.6% of the total population in South Australia), and

- 7% of assault victims in New South Wales (Indigenous Australians represented 3.6% of the total population in New South Wales (ABS 2019, 2022b).

Caution should be used when comparing numbers and rates of Indigenous assault victims across states and territories or time periods, due to variations in the proportion of victims with unknown Indigenous status – in 2021, Indigenous status was ‘not stated’ for 29% of assault victims in New South Wales, compared with 7% in the Northern Territory and 3% in South Australia (ABS 2022a).

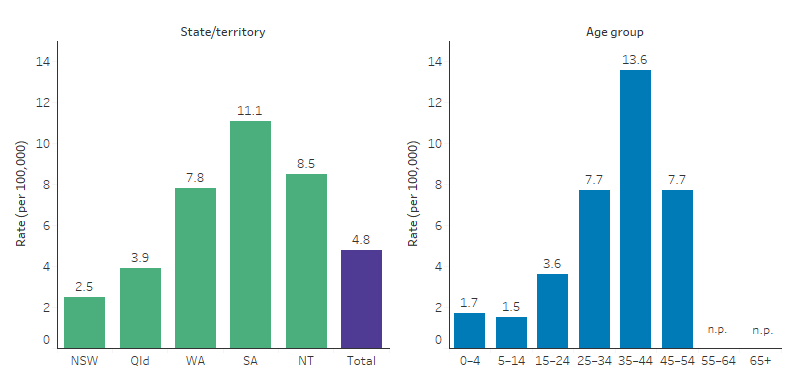

Homicide

Homicide data in this measure includes murder and manslaughter but excludes driving causing death. Data from the National Mortality Database is presented and is from five jurisdictions for which the quality of Indigenous identification in the deaths data is considered to be adequate. This includes: New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Data by remoteness are reported for all Australian states and territories combined (see Data sources: National Mortality Database).

In the five years 2015 to 2019, there were 174 deaths of Indigenous Australians due to homicide, a rate of 4.8 homicides per 100,000 population. Of these deaths almost two-thirds (63%) were deaths of Indigenous males. For Indigenous males the death rate due to homicide was 1.7 times the rate for Indigenous females.

For Indigenous Australians the rate of death due to homicide increased with age for all 10-year age groups from 5–14 to 35–44, where the rate was the highest for those aged 35–44 (14 per 100,000 population) (Figure 2.10.12). For Indigenous Australians aged 35–44 the rate of deaths due to homicide was 12 times as high as the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D2.10.7).

For Indigenous Australians in the period 2015 to 2019, of the five jurisdictions included in the analysis, the death rate due to homicide was highest in South Australia (11 deaths per 100,000 population) and lowest in New South Wales (2.5 per 100,000) (Figure 2.10.12). In South Australia, the rate of deaths due to homicide was 4.4 times as high as the rate in New South Wales.

Figure 2.10.12: Death rate by homicide of Indigenous Australians, by state and territory, by age group, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2015–2019

Sources: Tables D2.10.7 & D2.10.9. National Mortality Database.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, deaths due to homicide were:

- 6.3 times as high for Indigenous Australians as non‑Indigenous Australians

- 7.6 times as high for Indigenous females as for non-Indigenous females

- 5.8 times as high for Indigenous males as non-Indigenous males (Table D2.10.8).

Death rates due to homicide were higher for Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians in all five jurisdictions (based on age-standardised rates). The largest relative difference was in South Australia where the rate was 14 times as high as the non-Indigenous rate (Table 2.10.9).

An analysis of homicides in the period from 1989–90 to 2016–17 from the Australian Institute of Criminology’s National Homicide Monitoring Program show that in 87% (866) of homicides nationally where the victim was an Indigenous Australian, the perpetrator was also an Indigenous Australian (Table D2.10.26). Of these cases, 69% (595) were domestic homicides (Table D2.10.27).

For homicides in the period from 1989–90 to 2016–17, 72% (819) of Indigenous Australian offenders were under the influence of alcohol at the time of the incident, as were 71% (698) of Indigenous Australian victims. These were more than double the proportions for non-Indigenous Australian offenders (31%; 1,640) and victims (30%; 1,622) (Table D2.10.27).

Of homicides in the period from 2014–15 to 2016–17 in which the victim was an Indigenous Australian, 62% (53) were killed by a partner or family member and another 21% (18) by a friend or acquaintance. In comparison, non-Indigenous Australian victims were less likely to have been killed by a partner or family member (41%; 242) and more likely to have been killed by a friend or acquaintance (30%; 174) (Table D2.10.33).

The number of homicide incidents in which both the victim and perpetrator were Indigenous Australians increased by remoteness, from 10% (85) in Major cities to 62% (536) in Remote areas. Conversely, the number of homicides among non-Indigenous Australians decreased with remoteness, from 59% (3,035) in Major cities to 6% (307) in Remote areas (Table D2.10.30).

Contact with police and the criminal justice system

In 2014–15, 48% (101,200) of Indigenous males aged 15 and over reported that they had been charged by the police in their lifetime, and 20% (43,300) had been arrested by the police in the last five years. Fifty-eight per cent (256,700) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported that they trusted the police from their local area (ABS 2016) (Table 15.1, 15.3).

As at 30 June 2019, the majority (65%; 7,759) of Indigenous Australian prisoners had been incarcerated due to violence-related offences and offences that cause harm (Table D2.11.21). See measure 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system for further data about rates of imprisonment, interactions with the police, and socioeconomic characteristics associated with prisoners.

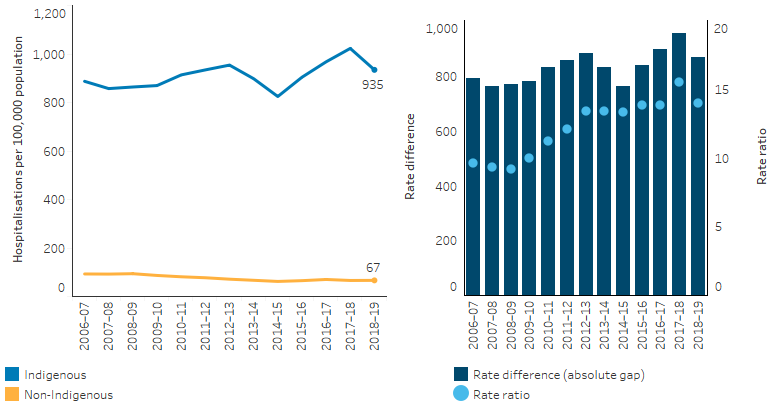

Change over time

Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, based on age-standardised rates, there was a 7.9% increase in the rate of assault hospitalisations among Indigenous Australians, compared with a 23.4% decrease among non-Indigenous Australians. This resulted in a widening of the gap between the two populations. These data represent six jurisdictions for which the quality of Indigenous identification in hospitals data was considered adequate for the time period considered: New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory.

The relative rate of hospitalisation due to assault among Indigenous Australians compared with non-Indigenous Australians generally increased between 2009–10 and 2018–19 – the rate in 2009–10 was 10 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians, compared with 14 times as high in 2018–19 (Table D2.10.11, Figure 2.10.13).

Figure 2.10.13: Age-standardised rates of assault hospitalisations, by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Notes

1. Data are for hospitalisations with a principal diagnosis of injury and poisoning, where the first reported external cause was assault.

2. Caution should be used when comparing this data over time, as the admission practices, classifications and coding standards can change.

3. Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D2.10.11. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Based on age-standardised rates, there was a 11% increase in the rate of hospitalisation of Indigenous females due to assault between 2009–10 and 2018–19 (from 814 to 914 per 100,000 population). For Indigenous males in the same period, there was little change to the hospitalisation rate (from 803 to 760 per 100,000 population) (Table D2.10.11).

Compared with the national average, the Northern Territory had a larger increase in hospitalisations due to assault in the decade between 2009–10 and 2018–19. The age-standardised rate of hospitalisations due to assault for Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory increased from 1,289 to 2,697 per 100,000 population (equivalent to nearly 3-fold or 184% increase, determined using linear regression analysis) in Outer regional areas, and from 2,324 to 3,144 per 100,000 population (nearly 1.5-fold or 42% increase) in Remote and Very remote areas. For non-Indigenous Australians in those areas, there was no change to the age-standardised rate in Remote areas, but there was an increase by 28% in Outer regional areas (Table D2.10.11, Table D2.10.17, Table D2.10.18).

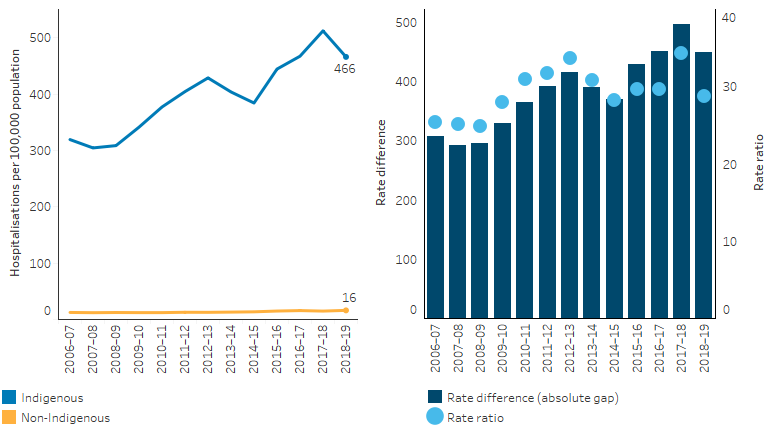

Over the period of 2009–10 to 2018–19, there was a 30% increase (from 316 to 415 per 100,000 population) in non-fatal hospitalisations due to family violence-related assaults for Indigenous Australians. The increases were higher among Indigenous females (35%) compared with Indigenous males (18%). During 2018–19, the rate of hospitalisations related to family violence for Indigenous females (629 per 100,000 population) was over 3 times as likely as Indigenous males (200 per 100,000).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 29 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for non-fatal family violence-related assaults in 2018–19. The gap in rates of family violence-related hospitalisations between Indigenous Australians and non-Indigenous Australians remained similar over the last decade, with hospitalisation rates in both populations increasing, by 36.8% and 35.9% respectively (in the six jurisdictions with Indigenous identification data of adequate quality) (Table D2.10.38, Figure 2.10.14).

Figure 2.10.14: Age-standardised non-fatal hospitalisation rates for family violence-related assaults, by Indigenous status, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D2.10.38. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

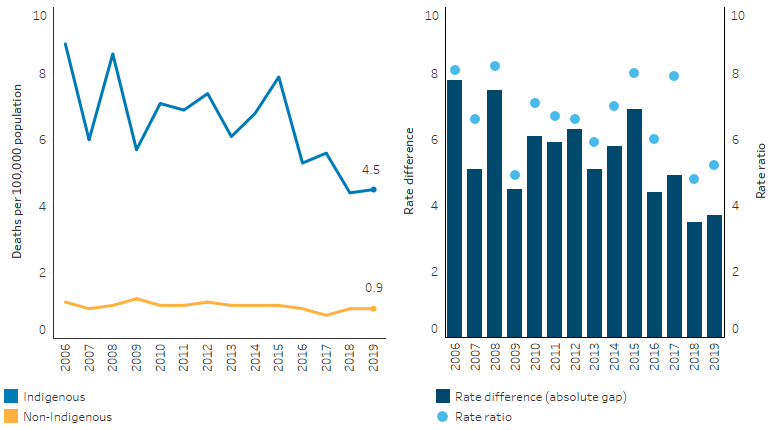

From 2010 to 2019, the age-standardised rates of deaths due to homicide for Indigenous Australians decreased by 37%. Over this period, the rate of death due to homicide also decreased for non-Indigenous Australians, though to a lesser extent (20% decrease), and there was a narrowing of the gap by 39% (Table D2.10.10, Figure 2.10.15).

Figure 2.10.15: Age-standardised death rates and changes in the gap due to homicide, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–2019

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D2.10.10. AIHW National Mortality Database.

Research and evaluation findings

Experiences of violence are associated with adverse health effects on the victim, their children and their family. Some key findings related to the health effects of violence are outlined below, which are not specific to Indigenous Australians unless otherwise stated:

- Throughout their lifetime, women who experience childhood abuse or household dysfunction have poorer health outcomes. These differences were evident across general health, physical function, bodily pain and mental health (Coles et al. 2015; Loxton et al. 2019).

- Women who face domestic violence are found to have higher rates of miscarriage, pre-term birth and low birthweight babies (World Health Organization 2011). They are also more likely to be diagnosed with cervical cancer or sexually transmitted infections (AIHW 2019b; Loxton et al. 2009).

- Women experiencing violence also have higher long-term primary, allied, and specialist health care costs, than women who have not had these experiences (Loxton et al. 2019).

- Poor family functioning can have negative effects on children, including effects on brain development, which can affect learning, behaviour and health. Children may also experience depression, anxiety, cognitive and developmental delays, and poor academic performance (Atkinson 2013; Carpenter & Stacks 2009; Edleson 1999; Humphreys et al. 2008; Kitzmann et al. 2003; Sety 2011).

- Physical violence (not family-specific) negatively affects the life satisfaction of both women and men and reduces the life satisfaction of Indigenous Australian women more than Indigenous men (Jayasinghe et al. 2020).

- Experiencing family violence can affect a person’s education, employment, economic security and housing (AIHW 2018; Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016).

As acknowledged by several prime ministers, Indigenous Australian families and family structures were severely damaged by past government policies and the colonial legacy (Atkinson 2013; Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016; Haebich 2000), the consequences of which are still evident.

Some of the factors believed to contribute to the high rates of violence within Indigenous communities include marginalisation and dispossession, the loss of land and traditional culture, the breakdown of community kinship systems and Aboriginal law, entrenched poverty, racism, alcohol and drug abuse, the effects of institutionalisation and removal policies; and the ‘redundancy’ of the traditional Aboriginal male role and status, compensated for by an aggressive assertion of male rights over women and children (Blagg Harry 1999).

Our Watch is a non-Indigenous organisation that provides resources and tools to help Australian communities to address violence against women and children, including but not limited to Indigenous Australians. Changing the picture, published by Our Watch in 2018 recognised that preventing violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children is a national responsibility and outlined actions to address the drivers of violence experienced by Indigenous women. The report included analysis of the ongoing effects of colonisation both within and from outside Indigenous communities, the ways in which non-Indigenous Australians continue forms of racism and violence, and gender specific factors that intersect with the aforementioned factors in different ways to drive violence (Our Watch 2018a, 2018b).

- For Indigenous Australians ongoing effects of colonisation include: intergenerational and collective trauma; systemic oppression, disempowerment, and racism; destruction/disruption of traditional cultures, relationships and community norms about violence; personal experience of violence; and the condoning of violence within Indigenous communities.

- Non-Indigenous Australians perpetuate the effects of colonisation through: racialised structural inequalities of power; entrenched racism in social norms, attitudes and practices; racist violence; and condoning of, and insufficient accountability for, violence against Indigenous Australians.

- Gender-specific factors caused by socially entrenched gender inequality can intersect with the factors above to drive violence such as: the disruption to traditional culture; rigid male and female roles; imposed colonial patriarchy; and male decision-making power.

The evidence on what works in reducing violence among Indigenous Australians remains inconclusive. However, from the few evaluations of family violence and community patrol programs, some successful principles are clear.

Aspects of successful family violence programs include community involvement in service planning; family focused case management; engagement and relationship building (which takes time); consideration of cultural factors; integrated service delivery; planning for long-term sustainability; and having a holistic focus and flexible, trauma-aware and healing-informed approaches. The barriers to effective programs include the lack of integrated and coordinated service delivery practices; unrealistic expectations and timelines set by governments and the community; applying a simplistic approach to policy development to deal with entrenched issues; operating with a lack of cultural awareness; and unsustainable responses that rely solely on short-term government funding (Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016).

Family Violence Prevention Legal Services (FVPLS) funded by the Australian Government aims to improve access to justice for victims of violence and improve safety through delivering culturally safe legal assistance, counselling, court support, education and community-based prevention services to change attitudes and behaviours regarding family violence. An impact, quality and outcomes evaluation in 2019 of the FVPLS by Charles Darwin University concluded that considerable improvements to practice across broad areas of their work was required, including systemic change, enhanced data collection and monitoring frameworks (Charles Darwin University Northern Institute 2019). In response, the National Indigenous Australians Agency collaborated with FVPLS providers to co-design program logic and best practice approaches to trauma-informed and culturally safe service delivery models, building the capacity and capability of FVPLS providers. The 2020-2023 funding agreements were then amended to address the needs identified in the evaluation and co-design process. FVPLS services now have targets to support First Nations individuals and their families across Australia and these are often exceeded by the service provider. The improved service delivery to Indigenous women and children living with family violence, and the over 140 early intervention and prevention of violence activities in communities and for families, are responsive to local needs and are practical in application.

Community patrols are one strategy instigated by some Indigenous communities for improving safety, sometimes known as a night patrol, foot patrol, street patrol, youth or women’s patrol. They have a diverse range of functions with patrols reflecting the different needs of local communities in remote and non-remote settings. Patrols are non-coercive and aim to help community members at risk from harm. They also aim to de-escalate tensions, divert people from situations that could lead to contact with the criminal justice system and connect people with support services such as sobering-up shelters or women’s refuges. In some communities there is no police presence and it can take several days for police to respond to calls leaving the patrols to deal with a matter.

Successful community patrols tend to benefit from community involvement and ownership, and strong collaboration with (but independence from) police and relationships with a network of community services. Other elements that appear to be important for the success of patrols include long-term government support, endorsement by key community members, good community governance, social cohesion, patrollers understanding their legal rights and their role and ensuring that the patrol is part of a holistic approach (Beacroft et al. 2011; Blagg Harry 2007). Patrols cannot work in isolation. They often cooperate closely with other community programs and initiatives such as women’s and youth refuges, health clinics and hospitals, safe houses, sobering-up shelters, mediation programs, community justice groups, alcohol and other substance abuse support services, youth centres, and outstations and homelands initiatives (Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2013).

Programs that simultaneously target victims, perpetrators and communities have been argued to be more effective considering the complexity of family violence within First Nations communities. One example of a simultaneous approach is the Aboriginal Family and Community Program that offers camps and counselling through either a men’s group, or an eight-week family wellbeing course for women. An evaluation of the program found it supported families in crisis, built community capacity to support safe families, and improved participants’ communication and conflict resolution skills (Cripps & Davis 2012). There are few robust formal evaluations of family violence prevention programs. Evaluations lack comparison groups and detailed assessments of the effects of programs on subsequent rates of violence. The use of different outcome measures across studies also makes it difficult to compare results (Day et al. 2013). There have been few published, rigorous, multi-stage evaluations of programs designed to reduce family violence in Indigenous communities. Little research has been done to explore the variation in violence levels and relative success of prevention programs (AIHW 2018).

Within First Nations communities, the effectiveness of domestic violence protection orders (DVOs) are contested. For example, Douglas and Fitzgerald (2018) found that DVOs within First Nations communities did not help victims but rather criminalised the victim which “contributes to the further enmeshment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in criminal justice processes” (Australian Human Rights Commission 2020; Heather & Robin 2018).

Victim support services are an important element in healing when it is appropriate to deliver services to the victim separate from the perpetrator. Australia’s National Research Organisation for Women’s Safety (ANROWS) (2021) identifies the following characteristics as being effective in healing and family violence programs for First Nations peoples:

- self-determination – developed, owned and managed by the community, and driven by local leadership

- locally specific – developed to address issues and needs within the local community

- sustainability – through the provision of adequate resources

- strengths-based and building on individual, family and community capacity

- collaborative partnerships between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal organisations that are based on respect and cultural competence

- respect and cultural competence

- transparency and accountability

- holistic approach, combining both mainstream and traditional methodologies

- innovative and multifaceted

- focus on the community as a whole

- evidence and theory-based

- incorporate culturally appropriate evaluation methodologies

- focus on rebuilding connections to culture, family, community and Country (Carlson et al. 2021).

Implications

Data from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey show that the majority of Indigenous Australians do not experience physical or threatened harm. However, for those that do, the effects can be severe and long-lasting. The nature of the effect is different for males and females, and the prevalence differs by age and remoteness. However, regardless of gender, age or remoteness, victims need access to appropriate, trauma-aware and healing-informed and culturally safe care and support.

The data also shows associations between experiences of physical or threatened harm and other social determinants such as low income, unemployment, alcohol and substance use. These associations reflect entrenched disadvantage and the intergenerational transmission of poverty, not unique to Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2017).

The monitoring of statistics regarding personal, family and community safety has an important role for providing evidence to support targeting efforts to assist communities, and to stimulate research into ways to reduce violence, improve safety, and improve services for victims. However, it is also important to note that this statistical catalogue of the level of violence is not intended to further entrench a deficit approach to addressing the issue by Australian governments. It establishes a statistical context based on what is currently collected across datasets that measure different concepts and interactions with different services or systems. What should not be overlooked is the capability, strength and resilience of Indigenous Australians in finding solutions to these issues for their communities. There is also a need to consider how non-Indigenous Australians and institutions have contributed to the causes of violence.

The Social Justice Report 2011 highlighted that lateral violence is intrinsically linked to disadvantage and the lack of participation in decision-making, false divisions over identity, and tension over who speaks for community and who participates in government consultations. The Social Justice Report urged governments to move from characterising Indigenous Australians as being dysfunctional and instead see Indigenous Australians as capable and resilient. Governments should work in ways that empower Indigenous Australians as they pursue solutions to these problems. A human-rights based framework for addressing lateral violence could offer solutions and should be based on the following principles: self-determination, participation in decision-making, non-discrimination and equality, and respect for and protection of culture (Australian Human Rights Commission 2011).

Actions should address the ongoing impact of colonisation for Indigenous Australians (Our Watch 2018b). This could include addressing intergenerational trauma through healing strategies; strengthening connection to culture, language, knowledge and cultural identity; strengthening support for families; implementing specific initiatives for Indigenous women and girls; implementing targeted initiatives for Indigenous men and boys; challenging the condoning of violence in Indigenous communities; having a judicial system that ensures equality in law and access to justice; and reducing the rate of incarceration (Our Watch 2018a, 2018b).

Non-Indigenous Australians and institutions have a role in addressing the effects of colonisation. For example, challenging and preventing all forms of racism; increasing non-Indigenous Australians’ understanding of Indigenous culture; increasing the representation of Indigenous Australians in decision-making; identifying and amending racist and discriminatory laws, policies and institutional practices; and challenging the condoning of violence against Indigenous Australians (Our Watch 2018a, 2018b). Violence does not only occur between Indigenous Australians. The homicide data illustrates that violence against Indigenous Australians perpetrated by non‑Indigenous Australians is real and should not be dismissed.

Actions taken to address violence against women should challenge racist and sexist attitudes and social norms (Our Watch 2018a, 2018b). These programs should take into consideration the perspective of Indigenous women. As pointed out by Nancarrow (2006), there is a split in the views among Indigenous and non-Indigenous women on the use of the criminal justice system and restorative justice in responding to violence (Nancarrow 2006). Indigenous women have expressed that the criminal justice system tends to reinforce state control and force the separation of Indigenous people. This leads to situations where women have felt a responsibility to maintain the family even when this puts their own safety at risk (Blagg H. et al. 2018). The overarching goal should be to end violence against women and children through empowerment, unity, and culturally relevant justice initiatives. For more information on justice initiatives see measure 2.11 Contact with the criminal justice system.

Improving the quality of Indigenous status identification across all relevant data sets should continue to be a priority. Comprehensive information on Indigenous family violence is limited by under-reporting by victims (for example, potentially due to the lack of culturally appropriate services, language differences and lack of trust in police (Mitra-Kahn et al. 2016; Olsen & Lovett 2016); lack of appropriate screening and identification of family and domestic violence incidents by service providers; incomplete identification of gender and inability to disaggregate data to produce reliable estimates to show geographical variation. There is a lack of nationally comparable data on family violence from police, courts, health and welfare sources (AIHW 2018).

All Australian governments recognise that a strong and coordinated response is needed to effectively address the issue of violence against women and children. The National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children 2010–2022 (the National Plan) was established to coordinate efforts across all levels of governments. In August 2019, the Council of Australian Governments endorsed the Fourth Action Plan of the National Plan agreeing on five national priorities to prevent family, domestic and sexual violence, and to support those affected with improved service system responses. The Australian Government is undertaking a comprehensive evaluation of the National Plan to improve understanding of the impact of the National Plan on reducing violence against women and their children.

The Australian Government has undertaken broad consultation to inform the development of the National Plan to End Violence against Women and Children 2022-2032.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Australian Government released an additional domestic violence support package under the National Plan to provide critical frontline services, including family support, safe houses and youth diversion to strengthen the capacity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to manage the ongoing impacts of the pandemic.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap has been developed in partnership between all Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement sets out ambitious targets and priority reforms that will change the way governments work to improve life outcomes experienced by Indigenous Australians.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

ABS 2016 (Australian Bureau of Statistics). National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey 2014–15. Cat. no. 4714.0. Canberra.

-

ABS 2019 Estimates and Projections, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, 2006 - 2031. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Viewed December 2022.

-

ABS 2022a. Recorded Crime - Victims. Viewed December 2022.

- ABS 2022b. National, state and territory population, March 2022. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics. Viewed December 2022.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2017. Australia's welfare 2017. Canberra.

- AIHW 2018. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia 2018. Canberra.

- AIHW 2019a. Australia's welfare 2019 Snapshot: Indigenous community safety. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2019b. Family, domestic and sexual violence in Australia: continuing the national story 2019. Author Canberra, Australian Capital Territory.

- Atkinson J 2013. Trauma-informed services and trauma-specific care for Indigenous Australian children. Closing the Gap Clearinghouse. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Australian Human Rights Commission 2011. Social Justice Report 2011. AHRC.

- Australian Human Rights Commission 2020. Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices): Securing Our Rights, Securing Our Future Report.

- Bartels L 2010. Emerging issues in domestic/family violence research. Australian Institute of Criminology, Criminology Research Council.

- Beacroft L, Richards K, Andrevski H & Rosevear L 2011. Community night patrols in the Northern Territory: Toward an improved performance and reporting framework. Australian Institute of Criminology Technical and Background Paper 47.

- Blagg H 1999. Intervening with adolescents to prevent domestic violence: Phase 2: The indigenous rural model. Canberra, Australia: National Crime Prevention.

- Blagg H 2007. Models of best practice: Aboriginal community patrols in Western Australia.

- Blagg H, Williams E, Cummings E, Hovane V, Torres M & Woodley KN 2018. Innovative models in addressing violence against Indigenous women: Final report (ANROWS Horizons, 01/2018). Sydney: ANROWS.

- Carlson B, Day M & Farrelly T 2021. What works? Exploring the literature on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander healing programs that respond to family violence. ANROWS.

- Carpenter GL & Stacks AM 2009. Developmental effects of exposure to intimate partner violence in early childhood: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review 31:831-9.

- Charles Darwin University Northern Institute 2019. Family Violence Prevention Legal Services National Evaluation Report. (ed., National Indigenous Australians Agency).

- Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2013. The role of community patrols in improving safety in Indigenous communities. (eds, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Closing the Gap Clearinghouse 2016. Family violence prevention programs in Indigenous communities. Vol. Resource sheet no. 37. Produced by the Closing the Gap Clearinghouse Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Coles J, Lee A, Taft A, Mazza D & Loxton D 2015. Childhood sexual abuse and its association with adult physical and mental health: results from a national cohort of young Australian women. Journal of interpersonal violence 30:1929-44.

- Cripps K & Davis M 2012. Communities working to reduce Indigenous family violence.

- Day A, Francisco A & Jones R 2013. Programs to improve interpersonal safety in Indigenous communities: evidence and issues. (ed., AIHW & AIFS). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Edleson JL 1999. Children's witnessing of adult domestic violence. Journal of interpersonal violence 14:839-70.

- Haebich A 2000. Broken circles. Fremantle Press.

- Heather D & Robin F 2018. The Domestic Violence Protection Order system as entry to the criminal justice system for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 7.

- Humphreys C, Houghton C & Ellis J 2008. Literature review: Better outcomes for children and young people experiencing domestic abuse: Directions for good practice.

- Jayasinghe M, Selvanathan EA & Selvanathan S 2020. Are effects of violence on life satisfaction gendered? A case study of Indigenous Australians. Journal of Happiness Studies:1-24.

- Kitzmann KM, Gaylord NK, Holt AR & Kenny ED 2003. Child witnesses to domestic violence: a meta-analytic review. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 71:339.

- Korff J 2015. Bullying & lateral violence. Viewed December 2022.

- Loxton D, Powers J, Schofield M, Hussain R & Hosking S 2009. Inadequate cervical cancer screening among mid-aged Australian women who have experienced partner violence. Preventive Medicine 48:184-8.

- Loxton D, Townsend N, Dolja-Gore X, Forder P & Coles J 2019. Adverse childhood experiences and healthcare costs in adult life. Journal of child sexual abuse 28:511-25.

- Mitra-Kahn T, Newbigin C & Hardefeldt S 2016. Invisible women, invisible violence: Understanding and improving data on the experiences of domestic and family violence and sexual assault for diverse groups of women: State of knowledge paper. Sydney: ANROWS.

- Nancarrow H 2006. In search of justice for domestic and family violence: Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australian women's perspectives. Theoretical Criminology 10:87-106.

- Olsen A & Lovett R 2016. Existing knowledge, practice and responses to violence against women in Australian Indigenous communities: State of knowledge paper. ANROWS.

- Our Watch 2018a. Changing the picture, Background paper: Understanding violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Melbourne: Our Watch. Retrieved from www. ourwatch. org. au.

- Our Watch 2018b. Changing the picture: A national resource to support the prevention violence against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and their children.

- Sety M 2011. The Impact of Domestic Violence on Children: A Literature Review. The Australian Domestic & Family Violence, Clearinghouse, The Benevolent Society, The University of New South Wales.

- World Health Organization 2011. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy. Geneva.