Key messages

- Reported ear or hearing problems declined from 11% in 2001 to 7% in 2018–19 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children aged 0–14. The rate of long-term reported ear or hearing problems in Indigenous children in this age group was over twice the rate for non-Indigenous children (6.9% compared with 3%) in 2018–19.

- There were 290,400 (43%) Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over with measured hearing loss in one or both ears in 2018–19, and the proportion was higher in remote areas (59%) than non-remote areas (39%).

- In 2018–19, 79% of Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over who were found to have measured hearing loss did not report having long-term hearing loss.

- As of December 2021, 3,403 Indigenous children and young people in the Northern Territory had outstanding referrals for hearing health services and were on waiting lists. This high number of outstanding referrals can be primarily explained by a shortage of available specialists.

- For Indigenous children aged 0–14, the rate of hospitalisation for ear disease was highest for those living in Remote and Very remote areas (13 and 15 hospitalisations per 1,000 population, respectively), compared with non-remote areas (7.8, 7.7 and 8.0 per 1,000 in Major cities, Inner regional areas and Outer regional areas respectively).

- Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, ear-related hospitalisations increased for Indigenous children aged 0–14 (from 6.9 to 8.7 hospitalisations per 1,000 population ) and for those aged 15 and over (from 1.4 to 2.3 hospitalisations per 1,000 population).

- Since the establishment of ear and hearing health outreach services in the Northern Territory in 2012, among those receiving the service, the proportion of Indigenous children and young people with at least one ear disease decreased by 10 percentage points (from 66% to 56%) and hearing loss decreased by 16 percentage points (from 55% to 39%) in 2020.

Why is it important?

Hearing loss among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is widespread and much more common than for non-Indigenous Australians (Burns & Thomson 2013; Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010). Hearing loss may result from several factors, including genetic causes, complications at birth, infectious diseases, chronic ear infections, use of certain medicines, injuries and accidents, exposure to loud noise and ageing. Worldwide, 60% of childhood hearing loss is due to preventable causes (WHO 2016). Otitis media (inflammation and infection of the middle ear) is a significant cause of hearing loss in Indigenous Australian children. The main forms of the disease include:

- acute otitis media (also known as a bulging eardrum) refers to fluid behind the eardrum plus at least one of the following: bulging or red eardrum, recent discharge of pus, fever, ear pain or irritability (Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010)

- otitis media with effusion (sometimes referred to as glue ear), which involves the presence of fluid behind the eardrum without any acute symptoms (Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010)

- chronic suppurative otitis media with discharge (sometimes referred to as runny ear/s) refers to persistent ear discharge through a persistent perforation (hole) in the eardrum lasting for more than two weeks (Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010; Leach & Morris 2017)

- chronic suppurative otitis media without discharge refers to a hole in the eardrum without evidence of discharge or fluid behind the ear (Standing Committee on Health & Aged Care and Sport 2017).

Otitis media in Indigenous children is characterised by earlier onset, higher frequency, greater severity and greater persistence than in non-Indigenous children (Jervis-Bardy et al. 2014; Kong et al. 2017). Several studies have found that Indigenous children living in remote communities experience high rates of severe and persistent ear infections (Edwards & Moffat 2014; Gunasekera H. et al. 2009; Kong & Coates 2009; Morris et al. 2007). Population surveillance across remote Northern Territory and Western Australian communities found that almost 90% of young children had otitis media (generally bilateral) and 14% to 20% had chronic suppurative otitis media (Leach & Morris 2017; Leach et al. 2014; Leach et al. 2016). Across the communities participating in the study since 2001, the proportion of young children with bilateral normal ears has been below 10% (Leach & Morris 2017; Leach et al. 2016; Morris et al. 2005). Overcrowded housing has been identified as a significant risk factor for otitis media, and exposure to campfire and tobacco smoke are also risk factors for early otitis media in infants (Leach & Morris 2017). Breastfeeding during the first six months of life can prevent many episodes of otitis media.

Hearing loss, especially in childhood, can lead to linguistic, social and learning difficulties and behavioural problems in school. Such difficulties may reduce educational achievements and have lifelong consequences for wellbeing, employment, income, social success, contact with the criminal justice system and attaining future potential (Burrow et al. 2009; Hogan et al. 2011; Williams & Jacobs 2009; Yiengprugsawan et al. 2013). Children with hearing problems may be at risk of developing mental health disorders, without appropriate intervention (Hogan et al. 2011).

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (the Health Plan), released in December 2021, provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing. The Health Plan was developed in genuine partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap.

Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure early intervention across the life course. Vital to manage the development or progression of health conditions over time, early intervention must focus on the conditions with the potential to become serious, but that are preventable and/or easily treatable.

Priority Five and Priority Seven of the Health Plan focus on early intervention and healthy environments which are crucially important to addressing hearing health for Indigenous Australians.

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Burden of disease

In 2018, hearing and vision disorders contributed 2.4% (5,833 DALY) of the total burden of disease for Indigenous Australians. Hearing loss accounted for 81% of the total burden of disease for hearing and vision disorders, and other hearing disorders contributed 7%.

Hearing loss was the largest cause of hearing and vision burden across all age groups, ranging from 38% of the burden for those aged 5–14 to 88% for those aged 25–44.

In 2018, the age-standardised rate of burden due to hearing and vision disorders for Indigenous Australians was 3.3 times that of non-Indigenous Australians. Hearing and vision loss contributed 3.6% of the gap in disease burden between the two populations (AIHW 2022b).

Data findings

Measured hearing loss

In 2018–19, the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Health Survey) offered a voluntary hearing test for participants aged 7 and over. An estimated 290,400 (43%) Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over were found to have hearing loss in one or both ears, and proportions were similar for both Indigenous males (43%) and females (42%).

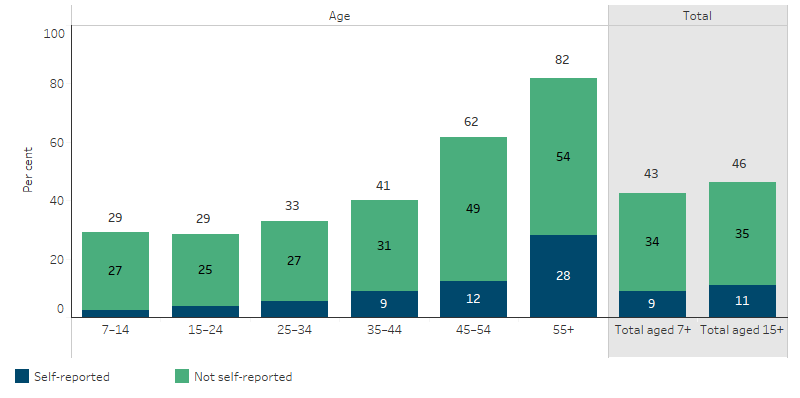

The proportion of measured hearing loss increased steadily with age, from 29% for Indigenous Australians aged 7–24, to 82% for those aged 55 and over (ABS 2019) (Figure 1.15.1).

Figure 1.15.1: Measured hearing loss, Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over, by age and whether self-reported hearing loss, 2018–19

Source: National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 (ABS Table 32.3).

Measured hearing loss for Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over was higher in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined) (59%) than non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner and Outer regional areas combined) (39%). Of Indigenous Australians aged 7 and over who were found to have measured hearing loss, 79% did not report having long-term hearing loss

Measured hearing loss was found to be clearly correlated with several key socioeconomic outcomes. For instance, among all Indigenous Australians who did not have any hearing loss, 41% had completed Year 12 or equivalent educational qualifications, while 56% were employed. The equivalent proportions among Indigenous Australians who had measured hearing loss in one or both ears were 26% and 40%, respectively. Among those with hearing loss in both ears, only 21% had completed Year 12 or equivalent, and 32% were employed.

The severity of the hearing loss (among Indigenous Australians with loss in both ears) also affected these outcomes. For instance, among those with severe or profound hearing loss, 18% had completed Year 12, and 17% were employed, compared with 23% with Year 12 and 36% employed among those with mild hearing loss (in both ears) (ABS 2019).

Reported ear health in children

Information in this section is based on data ‘as reported’ by survey respondents (adults on behalf of children) in the 2018–19 NATSIHS. Self-reported data may underestimate ear and hearing problems, for example if people are not aware that they have them. Based on these data, in 2018–19, around 19,100 Indigenous children aged 0–14 had reported ear or hearing problems. Indigenous children aged 0–14 had an ear or hearing problem at 2.3 times the rate of non-Indigenous children (6.9% compared with 3%). For Indigenous children, there was a decline in reported ear or hearing problems, from 11.2% in 2001 to 6.9% in 2018–19. The greatest decline was in remote areas, from 18% to 10% over the period (Table D1.15.3, Table 1.15-1).

Table 1.15-1: Proportion of children aged 0–14 with reported long-term ear or hearing problems, by Indigenous status and remoteness, 2001, 2004–05, 2008, 2012–13, 2014–15 and 2018–19

|

Indigenous status |

2001 |

2004–05 |

2008 |

2012–13 |

2014–15 |

2018–19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Indigenous |

11.2% |

9.5% |

8.5% |

7.1% |

8.4% |

6.9% |

|

Non-remote |

8.5% |

8.5% |

8.0% |

6.6% |

7.5% |

6.4% |

|

Remote |

17.7% |

12.6% |

10.3% |

9.1% |

11.4% |

9.7% |

|

Total non-Indigenous |

4.7% |

3.0% |

3.0% |

3.6% |

2.9% |

3.0% |

Source: Table D1.15.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19; and ABS National Health Survey 2017–18.

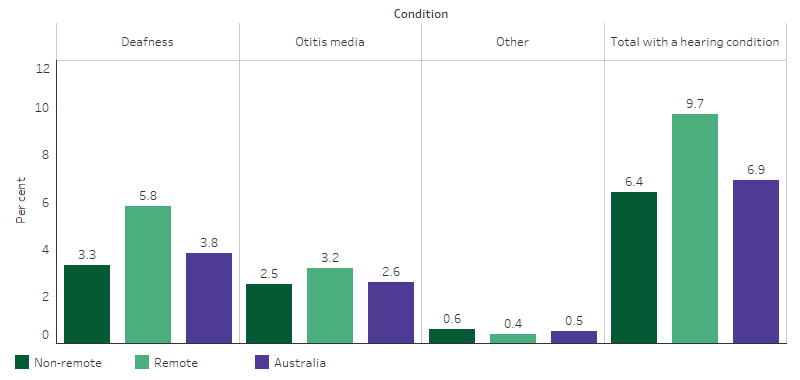

Total or partial deafness was reported for 3.8% of Indigenous children, otitis media (middle ear infection) for 2.6%, and other diseases of the ear for 0.5%. Rates of hearing problems among Indigenous children were higher in Remote areas (9.7%) than Non-remote areas (6.4%) (Table D1.15.3, Figure 1.15.2).

Figure 1.15.2: Proportion of Indigenous children aged 0–14 with long-term hearing problems, by type of ear or hearing problems and remoteness, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.15.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19; and ABS National Health Survey 2017–18.

Reported ear and hearing problems were less common among Indigenous children aged 0–3 (4%) than those aged 4–14 (8%). A higher proportion of Indigenous boys aged 0–14 reported ear or hearing problems (7.4%) than Indigenous girls of the same age (6.4%).

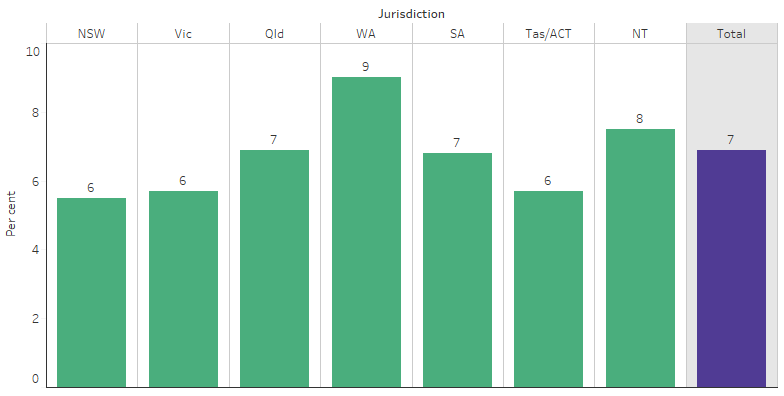

By jurisdiction, the rate of ear and hearing problems for Indigenous children in 2018–19 was highest in Western Australia (9%) and lowest in New South Wales (6%) (Table D1.15.9, Figure 1.15.3).

Figure 1.15.3: Proportion of Indigenous children aged 0–14 with reported ear or hearing problems, by jurisdiction, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.15.9. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

In 2014–15, of Indigenous children aged 0–14 with ear or hearing problems, 83% received some form of treatment, including:

- medication (including ear drops or antibiotics) (48%)

- checked by an ear or hearing specialist (46%)

- surgery (31%).

The remaining 16% of Indigenous children did not have any treatment for their ear and hearing problems. Not receiving treatment for ear or hearing problems was more common for Indigenous children in Remote areas (26%) than Non-remote areas (14%) (Table D1.15.20).

Reported ear health among all ages

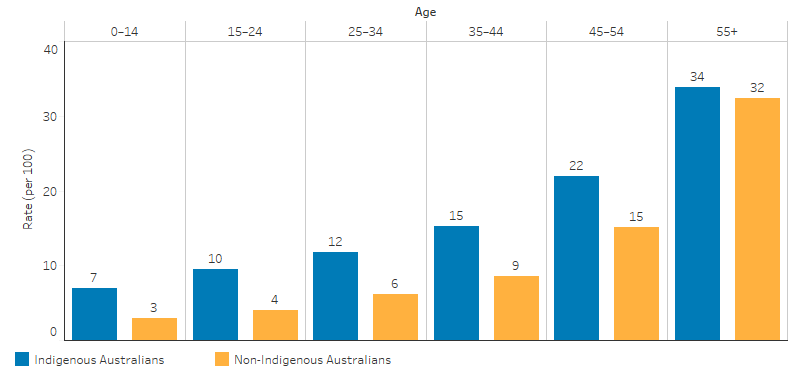

Data based on self-report from the 2018–19 NATSIHS showed that 14% (around 111,700) of Indigenous Australians had an ear or hearing problem (Table D1.15.4). Ear or hearing problems were reported for 7% of Indigenous children aged 0–14 and rose steadily to 34% for those aged 55 and over.

After adjusting for differences in age structure between the two populations, ear or hearing problems for Indigenous Australians were 1.4 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (17% and 13%, respectively). Indigenous Australians aged under 54 had higher rates of ear or hearing problems than non-Indigenous Australians, and rates for those aged 55 and over were similar between the two populations (34% and 32%, respectively) (Table D1.15.5, Figure 1.15.4).

Figure 1.15.4: Proportion of Australians with reported ear or hearing problems, by Indigenous status and age, 2018–19

Source: Table D1.15.5. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19 and National Health Survey 2017–18.

In 2018–19, after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, otitis media among Indigenous Australians was 3.3 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (1% compared with 0.3%), and deafness was 1.5 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (14% and 9%) (ABS 2019).

Indigenous Australians of all ages living in Non-remote areas reported an ear or hearing problem at similar rates to those in Remote areas (14% and 13%, respectively). By jurisdiction, the rate of Indigenous Australians reporting an ear or hearing problem was highest in the Australian Capital Territory (21%) and lowest in the Northern Territory (10%) (Table D1.15.4).

Of Indigenous Australians who reported ear or hearing problems (111,700), 17% reported using any hearing aids, the majority (12%) of which were for both ears. Hearing aid use for those with hearing problems was greater in non-remote areas, 18% compared with 12% for those in remote areas (Table D1.15.4). Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who lived in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (1st quintile) were 1.4 times as likely to report ear or hearing problems than those living in the most advantaged areas (5th quintile) (18% compared with 13%).

Of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who had completed Year 12, 15% had an ear or hearing problem compared with 23% of those who had completed Year 9 or below as their highest year of school.

Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over who reported their health as fair/poor (28%) were twice as likely to report having an ear or hearing problem as those reporting their health as excellent/very good/good (14%) (Table D1.15.6).

Ear health and hospitalisations

From July 2017 to June 2019, were 7,362 hospitalisations (equivalent to 4.4 per 1,000 population or 1.1% of total hospitalisations) for Indigenous Australians due to ear disease. Of these hospitalisations, one third were for children aged 0–4 (33%, 2,441), with around another third (34%, 2,531) for children aged 5–14 (Table D1.15.13, Table D1.02.1).

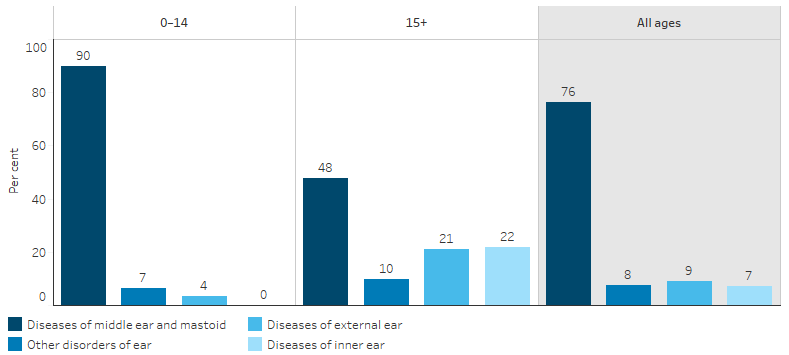

For Indigenous Australians, 76% of hospitalisations relating to the ear were for diseases of the middle ear and mastoid (5,607 of 7,362 hospitalisations) (Figure 1.15.5). This includes conditions such as acute otitis media and chronic suppurative otitis media, which are caused by viral and bacterial infections. The proportion of hospitalisations relating to the ear that were due to middle ear and mastoid diseases was lower for non-Indigenous Australians (53%) than for Indigenous Australians (76%) (Table D1.15.13).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous Australians were 1.3 times as likely as non-Indigenous Australians to be hospitalised for ear disease (3.8 and 2.8 hospitalisations per 1,000 population, respectively) (Table D1.15.12). Indigenous children aged 5–14 were 1.8 times as likely to be hospitalised for ear disease as non-Indigenous children of the same age group (6.9 compared with 3.8 hospitalisations per 1,000 population), with rates similar among Indigenous and non-Indigenous children aged 0–4 (12.9 and 12.2 per 1,000, respectively).

Figure 1.15.5: Principal diagnosis among Indigenous Australians hospitalised for diseases of the ear and mastoid process, by age, July 2017 to June 2019

Note: Denominator for percentages is the number of hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians in the specified age group that had a principal diagnosis of ear and mastoid process.

Source: Table D1.15.13. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

For Indigenous children aged 0–14, the rate of hospitalisation for ear disease was higher for those living in Remote and Very remote areas (12.8 and 14.5 hospitalisations per 1,000 population, respectively), compared with those living in Major cities (7.8 per 1,000 population), Inner regional areas (8.0 per 1,000 population) and Outer regional areas (7.7 per 1,000 population) (Table D1.15.14).

In the two-year period July 2018 to June 2020, the rate of myringotomy procedures (incision in the eardrum to relieve pressure caused by excessive fluid build-up) in hospital was 2.7 procedures per 1,000 population for Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022c). After adjusting for differences in the age-structure of the two populations, the rate of myringotomy procedures was 1.1 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians. Data on admissions to public hospitals from elective surgery waiting lists showed that the median elective surgery waiting time for myringotomy procedures was 75 days for Indigenous patients, compared with 62 days for non-Indigenous patients between July 2018 to June 2020.

During the same period, the rate of myringoplasty and tympanoplasty procedures (surgery to repair a hole in the eardrum) in hospital was 0.5 procedures per 1,000 population for Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022c). After adjusting for differences in the age-structure of the two populations, the rate of myringoplasty and tympanoplasty procedures was 2.5 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians. The median waiting time for admissions from public hospital waiting lists for myringoplasty/tympanoplasty procedures was 129 days for Indigenous Australians, shorter than for non-Indigenous Australians at 230 days.

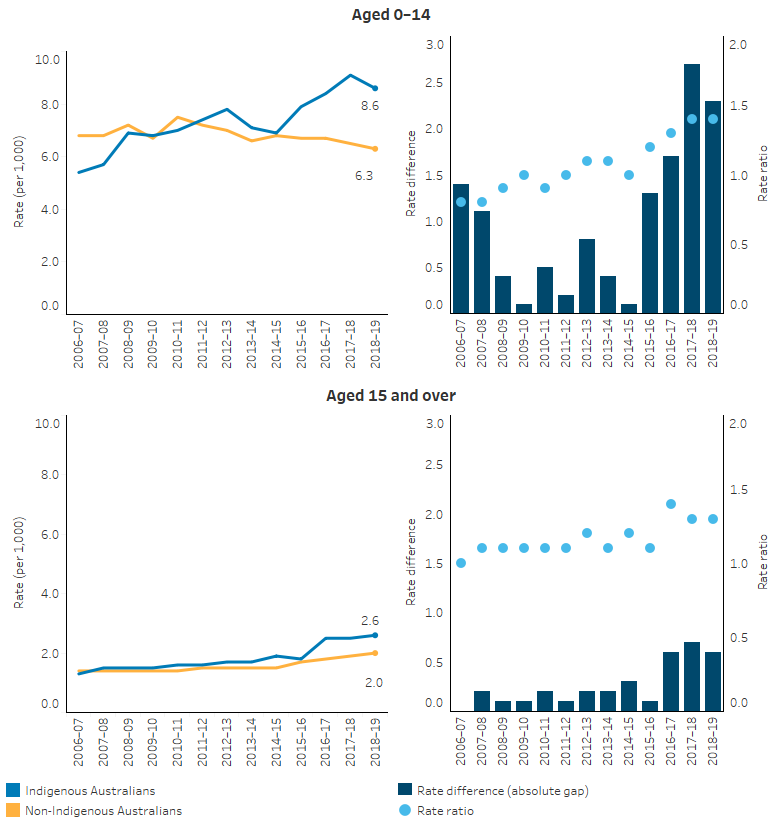

Hospitalisations trends presented in this section are for the six jurisdictions in which Indigenous identification in the hospitals data has been assessed as being of adequate quality over the time period considered (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory).

Over the decade between 2009–10 and 2018–19, in these six jurisdictions:

- ear-related hospitalisations for Indigenous children aged 0–14 generally increased, from 6.9 to 8.7 hospitalisations per 1,000 population

- ear-related hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over generally increased, from 1.4 to 2.3 hospitalisations per 1,000 population

Based on linear regression, which takes into account information from all years of the specified time period (see ‘Statistical terms and methods’), between 2009–10 and 2018–19, the hospitalisation rate for ear disease among Indigenous children aged 0–14 increased by 30%, while the rate for those aged 15 and over increased by 70%.

Over the period 2006-07 to 2018-19, and after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, for Indigenous children aged 0–14 there was a 29% increase (from 6.8 to 8.6 hospitalisations per 1,000 population) in ear-related hospitalisations, compared with an 11% decrease (from 6.7 to 6.3 per 1,000 population) for non-Indigenous children. For people aged 15 and over, there were increases in ear-related hospitalisations for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (85% compared with 46%) (Table D1.15.15, Figure 1.15.6).

Figure 1.15.6: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for principal diagnosis of diseases of the ear and mastoid process, by Indigenous status and age group, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA, NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 1,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D1.15.15. AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database.

Primary health care services and ear health

For Indigenous children aged 0–14, otitis media was managed by general practitioners (GPs) at a similar rate (67 per 1,000 encounters) to the rate for Other Australian children (64 per 1,000 encounters). Rates were also similar for total ear problems in 2010–15 (105 compared with 98 per 1,000 encounters, respectively) (Table D1.15.19).

Australian Government-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations provide access to ear, nose and throat specialists. These are provided onsite or though facilitating access to offsite facilities. In 2017–18, 22% of services were provided onsite only, 56% offsite only and 13% were a combination of onsite and offsite (AIHW 2019).

There are many activities funded by the Australian and state and territory governments to provide screening and supportive programs for Indigenous children and adults, and their families who are affected by ear conditions. For more information see Ear and hearing health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2021.

Queensland Deadly Ears program

The Deadly Ears program, established by Queensland Health in 2007, is a state-wide program for reducing the rates and effects of middle ear disease and conductive hearing loss (obstruction of hearing caused by fluid, infection, bone abnormality or perforated eardrum) for Indigenous children in Queensland.

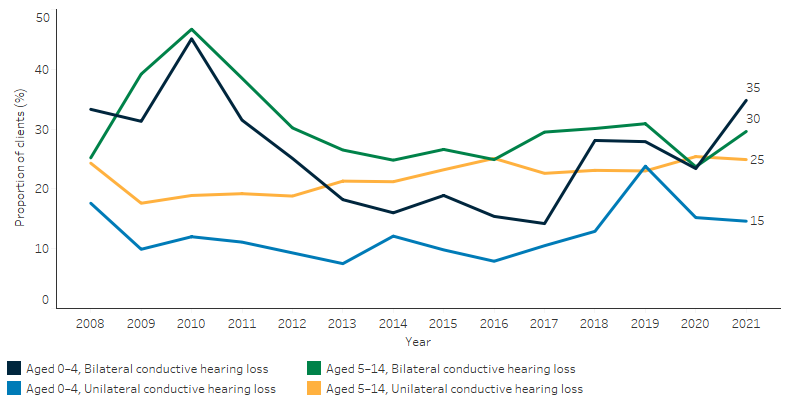

In 2021, 316 Indigenous children aged 0–4 and 790 aged 5–14 received an audiology assessment. Among the Indigenous children aged 0–4, 15% had hearing loss in one ear while more than one-third (35%) had hearing loss in both ears. For children in the older age group (5–14), 25% had hearing loss in one ear, and 30% had hearing loss in both ears (Table 1.15.17).

Indigenous children who had been diagnosed with middle ear dysfunction and whose condition had not been resolved with primary health management would be referred to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) assessment through the Deadly Ears Program. In 2021, 322 and 798 Indigenous children aged 0–4 and 5–14 received the specialist assessment, respectively, and about half of them were found to have some form of ear inflammation or infection (otitis media) (Table D1.15.18).

Over the period 2008 to 2021, data collected through the Queensland Deadly Ears program showed that of the 3,559 Indigenous children aged 0–4 who received an audiology assessment, 24% of them had hearing loss in both ears and 12% in one ear. For the 9,269 Indigenous children aged 5–14 who received an audiology assessment, 29% had hearing loss in both ears and 22% in one ear (Table D1.15.17, Figure 1.15.7).

Figure 1.15.7: Proportion of Deadly Ears Program clients who received an audiology assessment, by hearing loss and age group, Queensland, 2008–2021

Source: Table D1.15.17. Deadly Ears program data.

Of the 5,506 Indigenous children aged 0–4 who had been diagnosed with middle ear dysfunction and referred to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) assessment through the Deadly Ears Program during 2007–2022, 11% had chronic suppurative otitis media, 6% had dry perforation, and 32% had otitis media with effusion. Of the 12,241 Indigenous children aged 5–14 who received an ENT assessment, 9% had chronic suppurative otitis media, 10% had dry perforation, and 20% had otitis media with effusion (Table D1.15.18).

Northern Territory ear and hearing health outreach services

Since 2012, the Australian Government has funded the Northern Territory Government to deliver hearing health outreach services to Indigenous children and young people aged under 21 in the Northern Territory. Data of clients using these outreach services were collected.

In 2021:

- 2,290 audiology services were provided to 1,979 Indigenous children and young people.

- 703 ear, nose and throat services were provided to 635 children and young people.

- 1,987 children and young people received at least 1 audiology (Clinical Nurse Specialist or ear, nose and throat) service.

As of December 2021, 3,403 Indigenous children and young people had outstanding referrals for hearing health services and were on waiting lists, a high number primarily explained by a shortage of available specialists.

At their last service provision, 56% (1,113) of Indigenous children and young people receiving hearing health outreach services were diagnosed with at least 1 type of ear condition:

- 22% had otitis media with effusion

- 22% had Eustachian tube dysfunction

- 11% had chronic suppurative otitis media without discharge

- 6.4% had chronic suppurative otitis media with discharge (AIHW 2022a).

Among the Indigenous children and young people (aged under 21) receiving hearing health outreach services in Northern Territory, the percentage of Indigenous children and young people with at least one ear disease decreased by 10 percentage points, from 66% (483 of 727 clients) to 56% (1,113 of 1,987 clients) between 2012 and 2021. The proportion of children and young people with hearing loss decreased by 16 percentage points, from 55% (388 of 710 clients) to 39% (776 of 1,979 clients) between 2012 and 2021 (AIHW 2022a).

Research and evaluation findings

Using data linkage, an observational cohort study of 3,744 Indigenous children in the Northern Territory found that Indigenous children with any level of hearing impairment were likely to have lower school attendance rates in Year 1 than their peers with normal hearing (Su et al. 2019). The effect of unilateral hearing loss (normal in one ear and any degree of hearing loss in the other ear) on school attendance was similar to the effect of mild and moderate hearing loss.

A retrospective cohort study of 1,533 Indigenous children from remote Northern Territory communities used linked individual-level information to investigate the association between hearing impairment in early childhood and youth offending (He et al. 2019). This study demonstrated a high prevalence of hearing impairment among Indigenous children with a record of an offence (boys: 55.6%, girls: 36.7%) and those without an offence record (boys: 46.1%, girls: 49.0%). In univariate analysis, a higher risk of offending was found among Indigenous boys with moderate or worse hearing impairment, but no evidence of an association was found among Indigenous girls. However, after controlling for other factors, such as community factors, child maltreatment and Year 7 school attendance, an association between hearing impairment and youth offending was not evident. The reasons for the lack of an association for Indigenous boys after adjusting for other factors is unclear, and it is possible that the effects of hearing impairment were masked by the much stronger effect of child maltreatment and community factors.

A study monitoring the prevalence of suppurative otitis media in Indigenous children in remote Northern Territory from 2010 to 2013 found that otitis media was rarely associated with pain (as reported by their parents) (Leach et al. 2016). Early-onset of otitis media may be a factor in asymptomatic acute otitis media among Indigenous children—as documented over many years (Leach et al. 2016; Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2010). This means that parents and health-care providers can be unaware of infections, which go untreated and become chronic (Leach & Morris 2017). Evidence suggests that diagnostic inaccuracy for otitis media is common (Blomgren & Pitkäranta 2003; Blomgren et al. 2004; Garbutt et al. 2003) and leads to delayed treatment, under- or over-treatment and an increased risk of complications, including hearing loss and antibiotic resistance (Gunasekera Hasantha et al. 2007; Lieberthal et al. 2013; WHO 2013). In some remote communities, otitis media has become normalised, and parents are unlikely to seek treatment (Leach & Morris 2017; Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2010).

For Indigenous Australians who had been diagnosed and treated, a study of 419 myringoplasty operation outcomes in the West Kimberley from 2004 to 2014 found that follow-up and outcomes remain poor for Indigenous Australians. Only 21.5% of operations had complete follow-up. Of those with complete follow-up, 29% had closure of the tympanic membrane with normal hearing. Success rates were higher among patients with dry ears before the operation.

Social determinants associated with ear health

One of the risk factors commonly identified in the literature is exposure to tobacco smoke. Tobacco smoking rates among Indigenous Australians remain high (see measures 2.03 Environmental tobacco smoke and 2.15 Tobacco use). Exposure to tobacco smoke can cause middle ear infection (Jacoby et al. 2008; Jervis-Bardy et al. 2014; Office on Smoking and Health (US) 2006) and exposure to tobacco and campfire smoke are risk factors for early otitis media in infants (Leach & Morris 2017).

Otitis media is also associated with crowded housing conditions, nutritional deficiencies and poverty (Burns & Thomson 2013; DeLacy et al. 2020; Jacoby et al. 2011). Overcrowding, in particular, is a consistent risk factor for upper respiratory tract carriage (presence of bacteria), and consequently, the development of otitis media in both Indigenous and non-Indigenous children (Jacoby et al. 2011).Overall social and economic disadvantage, such as lower levels of education and lack of employment among parents and carers, can also contribute to high rates of untreated acute and chronic ear infections (Leach & Morris 2017).

Prevention and treatment initiatives

The Deadly Ears Deadly Kids Deadly Communities Framework 2009–2013 was developed in Queensland to address otitis media in Indigenous children spanning areas of prevention, detection and surveillance, treatment, partnerships and workforce. An evaluation showed a reduction in presentations of chronic suppurative otitis media in children from 2009–10 to 2013–14 (using Deadly Ears Clinic data), following health promotion and education activities in 2010. There was also improved access to appropriate specialist and mainstream services to treat and manage otitis media and other ear and hearing problems, and improved learning and development support within schools for children affected by otitis media (Durham et al. 2015). A separate but related evaluation concluded that sustained progress in improving the ear health of Indigenous children requires a holistic, system-wide approach with the appropriate government structures geared towards multi-sector involvement, shared system-level goals and system-wide feedback processes (Durham et al. 2018).The Deadly Kids Deadly Futures: Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Ear and Hearing Health Framework 2016–2026 aims to strengthen the primary health-care sector to diagnose and manage the effects of middle ear disease and associated hearing loss as part of routine child health checks and provide opportunistic care on every occasion of service. In addition, the framework will track progress in health, early childhood and schooling sectors with targets and actions aimed at health promotion and prevention, improvements to services, workforce development and data collection and research (State of Queensland 2016).

Tools have been developed to help health professionals, teachers and early childhood professionals to work with parents to identify Indigenous children who may be at risk of hearing and communication issues. The Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/oral performance of Children (PEACH) ear health screening questionnaire was developed and validated for use with young children in the general population who have unimpaired or impaired hearing (National Acoustic Laboratories 2018). The Parent-evaluated Listening and Understanding Measure (PLUM) is an adaptation of the PEACH to be suitable for the Indigenous Australian context. The Hear and Talk Scale (HATS) was also developed to identify children who may have speech communication difficulties. The PLUM and HATS were co-designed with Indigenous and non-Indigenous primary health and early childhood professionals (National Acoustic Laboratories 2020) and have been validated for use with Indigenous Australian children aged 0–5 (National Acoustic Laboratories 2018). These tools make use of parents’ and carers’ observations of children in everyday situations and can reveal early signs of hearing difficulty and hindered language development to assist with early intervention (DoH 2020).

The Department of Health engaged a consultant to undertake an examination of the six Indigenous Ear and Hearing Health Initiatives funded under the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (Siggins Miller Consultants 2017). This evaluation found that, while these programs facilitated and improved access to multidisciplinary ear health care for Indigenous children and young people, the evidence suggests the burden of disease has not significantly declined. One of the key recommendations at the program level was for more communication about the programs to Indigenous communities, service providers, peak bodies, State and Territory governments and other stakeholders. Another recommendation was to require adherence to the National Otitis Media Clinical Care Guidelines as a condition of Commonwealth funding. While the evaluation found that the Guidelines were influential and there was evidence of their increasing use by service providers, it also noted there were systemic barriers to service providers following the recommended care pathway and delivering timely care to children with or at risk of developing ear disease.

Implications

Rates of GP management of ear problems and otitis media for Indigenous children 0–14 years are similar to non-Indigenous rates, yet the prevalence of self-reported ear or hearing problems is over twice as high. Self-reported ear and hearing problems have been shown to be under-reported in the Indigenous Australian population, particularly children, with 92% of Indigenous children aged 7–14 years with measured hearing loss not reporting they had a long-term hearing impairment in 2018-19 (ABS 2020).

For some forms of ear disease, the recommendation for children in populations not at high risk of chronic suppurative otitis media is to ‘watch and wait’ (Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010). Hospitalisation rates for myringotomy are similar for Indigenous Australians and other Australians, as are wait times for myringotomy procedures in public hospitals. This suggests that health services and hospitals are not yet meeting the need for treating ear or hearing problems for Indigenous Australians.

The regular collection of data on the prevalence of measured hearing loss among Indigenous Australians, in addition to the self-reported estimates traditionally collected in the Health Survey, remains a priority given the high rates of measured hearing loss found nationally in the 2018–19 Health Survey. There remains a gap in the national measured hearing loss data for Indigenous children aged under 7.

A comprehensive approach combining prevention, early treatment and coordinated management is required to reduce the incidence of hearing loss among Indigenous Australians. Primary prevention includes working with families on encouraging breastfeeding (Bowatte et al. 2015) eating a healthy diet, reducing exposure to second-hand smoke, nasal passage clearing, seeking early medical assessment and encouraging vaccination.

Otitis media and hearing loss have become normalised in some remote communities and can go unrecognised with parents rarely seeking help for these conditions (Leach & Morris 2017). Therefore, routine and regular surveillance for hearing loss and regular ear checks in the neonatal and pre-school period is recommended for Indigenous children given the high prevalence of otitis media. Routine child health checks, including an assessment of Indigenous children’s ear health on each occasion of contact with a health service, are needed to monitor hearing health in the case of recurrent infections, and to support the identification of issues associated with hearing loss such as delays in speech and language development and impaired listening skills.

Once otitis media develops, medical management should be consistent with the Recommendations for Clinical Care Guidelines on the Management of Otitis Media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations. When hearing loss is detected, access and referral to a range of health services is needed, including speech therapists and audiology support services (Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group 2010). If permanent hearing loss is detected, access and referral to support for hearing augmentation and other remedial therapies should be sought.

In addition to a focus on 0–4 year olds for early identification and intervention, detection and management of hearing loss on entry into primary school should be included in measures to help improve school attendance (Su et al. 2019). As with younger children, this approach should be considered as part of a “whole-of-child” check to support the identification of other developmental impacts associated with hearing loss. Strategies in schools such as classroom management strategies, language therapy, and sound amplification have been successful tools for those with hearing impairment (Burns & Thomson 2013; Massie et al. 2004).

Working in partnership with local communities and health services is important for building culturally appropriate services and maintaining community buy-in. The Hearing for Learning Initiative trains and employs Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community members as ear health project officers in the Northern Territory. They help primary care services and health professionals diagnose and manage ear disease or refer children for specialist treatment. The goal is to work with communities to establish reliable, sustainable, culturally appropriate services that ensure every ear of every child is healthy and hearing every day.

Another example is the Hearing Assessment Program – Early Ears (HAPEE) which aims to prevent hearing loss in Indigenous children in the years before they start school. Hearing Australia delivers the program in consultation with communities and health services. Audiologists provide ear and hearing health assessments and recommendations for any follow-up care as required.

The discrepancy between self-reported and measured hearing loss underscores the importance of routine surveillance to objectively detect ear and hearing problems as part of whole-of-child health checks.

Practical, evidence-based indicators to support the continuous quality improvement of health services in the management of otitis media in Indigenous children were developed by a group of experts, including working in Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (Sibthorpe et al. 2017). The indicators cover routine surveillance, incidence of ear disease, appropriate prescribing, audiological testing, care planning and timely follow-up.

Current interventions are primarily focused on medical approaches, such as antibiotics and surgical procedures. While these are essential, a broader public health lens is required to address the underlying social determinants that are driving the high rates of otitis media among Indigenous children, including overcrowding (DeLacy et al. 2020). A significantly increased focus on both primordial prevention to address these social determinants and primary prevention, including family and community health literacy about otitis media, is needed (Australian Medical Association 2017).

The Health Plan is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap health targets and priority reforms. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities.

Prevention and early intervention are key aspects of the Health Plan with a strong emphasis on place-based approaches that are locally determined. For example, some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities are more strongly impacted by heart, ear or eye conditions. Therefore, place-based approaches must also embed multidisciplinary care and partnerships. They must include pathways through primary health care (including identification of symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and follow-up care) to allied, specialist and tertiary care.

Priority Five of the Health Plan focuses on early intervention approaches that are accessible to Indigenous Australians and provide timely, high quality, effective, culturally safe and responsive care. The Health Plan recognises that for some communities a focus on preventing hearing loss resulting from ear infections will be an important priority.

Priority Seven focuses on healthy environments recognising that appropriately sized and functioning homes are important for preventing and controlling illnesses such as trachoma, otitis media and acute rheumatic fever.

The Roadmap for Hearing Health is a framework aiming to support all Australians who are deaf or hard of hearing to live well in the community. The second domain — Closing the Gap for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Ear and Hearing Health — aims to address the catastrophic levels of ear disease amongst Indigenous Australians. Priorities for action include raising awareness among Indigenous communities, and implementing an integrated approach to ear health checks among children aged 0-6 (Hearing Health Sector Committee 2019).

The Ear Health Coordination Program (EHCP) co-designed by the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation, the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council, and the NSW Rural Doctors Network in 2019, aims to increase state and jurisdictional coordination of services that support and respond to the ear health needs of Indigenous children across New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory. It will enhance the monitoring and treatment of ear and hearing health in primary care and particularly focus on the access to quality, culturally safe ear and hearing health services for Indigenous children before they commence primary school. The program also aims to integrate a continuous quality improvement approach in all activities, improve data collection on ear disease, and online training resources. As the program continues to be implemented, it is anticipated that there will be an increase in children and youth accessing services and reporting a more positive experience.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2020. 'Under-reporting of hearing impairment in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population', National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19. Vol. Cat No. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS.

-

AIHW 2019. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report — key results 2017–18. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Hearing health outreach services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in the Northern Territory: July 2012 to December 2021. AIHW, Australian Government.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. AIHW, Australian Government.

- AIHW 2022c. Ear and hearing health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2021.

- AIHW 2022d. Admitted patient care 2020–21. Canberra: AIHW.

- Australian Medical Association 2017. 2017 AMA Report Card on Indigenous Health - A National Strategic Approach to Ending Chronic Otitis Media and its Life Long Impacts in Indigenous Communities. AMA.

- Blomgren K & Pitkäranta A 2003. Is it possible to diagnose acute otitis media accurately in primary health care? Family Practice 20:524-7.

- Blomgren K, Pohjavuori S, Poussa T, Hatakka K, Korpela R & Pitkäranta A 2004. Effect of accurate diagnostic criteria on incidence of acute otitis media in otitis-prone children. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases 36:6-9.

- Bowatte G, Tham R, Allen KJ, Tan DJ, Lau M, Dai X et al. 2015. Breastfeeding and childhood acute otitis media: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatrica 104:85-95.

- Burns J & Thomson N 2013. Review of ear health and hearing among Indigenous Australians. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet No 15.

- Burrow S, Galloway A & Weissofner N 2009. Review of educational and other approaches to hearing loss among Indigenous people. Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet.

- Darwin Otitis Guidelines Group & Office for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Otitis Media Technical Advisory Group 2010. Recommendations for Clinical Care Guidelines on the Management of Otitis Media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Populations. Darwin: Menzies SHR.

- DeLacy J, Dune T & Macdonald JJ 2020. The social determinants of otitis media in Aboriginal children in Australia: are we addressing the primary causes? A systematic content review. BMC Public Health 20:1-9.

- DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) 2020. Related resources for health professionals PLUM and HATS. Viewed 13 September 2020.

- Durham J, Schubert L & Vaughan L 2015. Deadly ears deadly kids deadly communities framework: Evaluation report.

- Durham J, Schubert L, Vaughan L & Willis CD 2018. Using systems thinking and the Intervention Level Framework to analyse public health planning for complex problems: Otitis media in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. PloS one 13:e0194275.

- Edwards J & Moffat CD 2014. Otitis media in remote communities. Australian Nursing & Midwifery Journal 21:28.

- Garbutt J, Jeffe DB & Shackelford P 2003. Diagnosis and treatment of acute otitis media: an assessment. Pediatrics 112:143-9.

- Gunasekera H, Knox S, Morris P, Britt H, McIntyre P & Craig JC 2007. The spectrum and management of otitis media in Australian indigenous and nonindigenous children: a national study. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 26:689-92.

- Gunasekera H, Morris PS, Daniels J, Couzos S & Craig JC 2009. Otitis media in Aboriginal children: the discordance between burden of illness and access to services in rural/remote and urban Australia. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 45:425-30.

- He VY, Su J-Y, Guthridge S, Malvaso C, Howard D, Williams T et al. 2019. Hearing and justice: The link between hearing impairment in early childhood and youth offending in Aboriginal children living in remote communities of the Northern Territory, Australia. Health & Justice 7:16.

- Hogan A, Shipley M, Strazdins L, Purcell A & Baker E 2011. Communication and behavioural disorders among children with hearing loss increases risk of mental health disorders. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 35:377-83.

- Jacoby P, Carville KS, Hall G, Riley TV, Bowman J, Leach AJ et al. 2011. Crowding and other strong predictors of upper respiratory tract carriage of otitis media-related bacteria in Australian Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children. The Pediatric infectious disease journal 30:480-5.

- Jacoby PA, Coates HL, Arumugaswamy A, Elsbury D, Stokes A, Monck R et al. 2008. The effect of passive smoking on the risk of otitis media in Aboriginal and non‐Aboriginal children in the Kalgoorlie–Boulder region of Western Australia. Medical Journal of Australia 188:599-603.

- Jervis-Bardy J, Sanchez L & Carney AS 2014. Otitis media in Indigenous Australian children: review of epidemiology and risk factors. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 128 Suppl 1:S16-27.

- Kong K & Coates HLC 2009. Natural history, definitions, risk factors and burden of otitis media. The Medical Journal of Australia 191:39.

- Kong K, Lannigan FJ, Morris PS, Leach AJ & O'Leary SJ 2017. Ear, nose and throat surgery: All you need to know about the surgical approach to the management of middle‐ear effusions in Australian Indigenous and non‐Indigenous children. Journal of paediatrics and child health 53:1060-4.

- Leach A & Morris P 2017. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Health, Aged care and Sport Inquiry into the Hearing Health and Wellbeing of Australia - Submission 108. Canberra: Menzies School of Health Research.

- Leach AJ, Wigger C, Andrews R, Chatfield M, Smith-Vaughan H & Morris PS 2014. Otitis media in children vaccinated during consecutive 7-valent or 10-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccination schedules. BMC pediatrics 14:200.

- Leach AJ, Wigger C, Beissbarth J, Woltring D, Andrews R, Chatfield MD et al. 2016. General health, otitis media, nasopharyngeal carriage and middle ear microbiology in Northern Territory Aboriginal children vaccinated during consecutive periods of 10-valent or 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology 86:224-32.

- Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, Ganiats TG, Hoberman A, Jackson MA et al. 2013. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics 131:e964-e99.

- Massie R, Theodoros D, McPherson B & Smaldino J 2004. Sound-field Amplification: Enhancing the Classroom Listening Environment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 33:47-53.

- Morris PS, Leach AJ, Halpin S, Mellon G, Gadil G, Wigger C et al. 2007. An overview of acute otitis media in Australian Aboriginal children living in remote communities. Vaccine 25:2389-93.

- Morris PS, Leach AJ, Silberberg P, Mellon G, Wilson C, Hamilton E et al. 2005. Otitis media in young Aboriginal children from remote communities in Northern and Central Australia: a cross-sectional survey. BMC pediatrics 5:27.

- National Acoustic Laboratories 2018. Norming and validating the Parent-evaluated Listening & Understanding Measure (PLUM) and Hear and Talk Scale (HATS) for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander children aged 0 to 5 years. Viewed 13 September 2020.

- National Acoustic Laboratories 2020. PLUM & HATS. Viewed 13 September 2020.

- Office on Smoking and Health (US) 2006. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. (ed., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US)). Atlanta: CDCP (US).

- Oguoma VM, Wilson N, Mulholland K, Santosham M, Torzillo P, McIntyre P et al. 2020. 10-Valent pneumococcal non-typeable H. influenzae protein D conjugate vaccine (PHiD-CV10) versus 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13) as a booster dose to broaden and strengthen protection from otitis media (PREVIX_BOOST) in Australian Aboriginal children: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 10:e033511.

- Senate Community Affairs References Committee 2010. Hear us: inquiry into hearing health in Australia. Canberra.

- Sibthorpe B, Agostino J, Coates H, Weeks S, Lehmann D, Wood M et al. 2017. Indicators for continuous quality improvement for otitis media in primary health care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Australian journal of primary health 23:1-9.

- Siggins Miller Consultants 2017. Examine Australian Government Indigenous Ear and Hearing Health Initiatives Final Report. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health.

- Standing Committee on Health, Aged Care and Sport 2017. Still waiting to be heard... Report on the Inquiry into the Hearing Health and Wellbeing of Australia. Canberra: The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia.

- State of Queensland 2016. Deadly Kids, Deadly Futures: Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Child Ear and Hearing Health Framework 2016-2026. Brisbane: State of Queensland.

- Su J-Y, He VY, Guthridge S, Howard D, Leach A & Silburn S 2019. The impact of hearing impairment on Aboriginal children’s school attendance in remote Northern Territory: a data linkage study. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 43:544-50.

- WHO (World Health Organization) 2013. Millions of people in the world have hearing loss that can be treated or prevented. Geneva: WHO:1-17.

- WHO 2016. Deafness and hearing loss fact sheet. Geneva: WHO; 2015.

- Williams CJ & Jacobs AM 2009. The impact of otitis media on cognitive and educational outcomes. The Medical Journal of Australia 191:S69-S72.

- Yiengprugsawan V, Hogan A & Strazdins L 2013. Longitudinal analysis of ear infection and hearing impairment: findings from 6-year prospective cohorts of Australian children. BMC pediatrics 13:28.