Key messages

- Of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with indicators of chronic kidney disease in the 2012–13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, only 11% had reported having the condition and 89% did not know they had it.

- Chronic kidney disease (kidney conditions lasting 3 months or longer) accounted for 2.5% of total disease burden for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in 2018.

- Between 2010 and 2019, age-standardised death rates for kidney disease (including acute and chronic kidney disease) among Indigenous Australians declined by 36% and by 26% for non-Indigenous Australians. However, the gap in the rates for the two populations did not change significantly over this period.

- Between July 2017 and June 2019, dialysis, which is used to treat kidney failure was the leading cause of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians (44% of hospitalisations).

- The rate of hospitalisation for care involving dialysis was 11 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians, based on age-standardised rates (453 and 42 per 1,000, respectively).

- Between July 2017 and June 2019, Indigenous females were twice as likely to be hospitalised for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) as Indigenous males (crude rates of 5.4 and 2.7 per 1,000, respectively).

- The rate of burden due to chronic kidney disease for Indigenous Australians was 8 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (13 and 1.7 DALY per 1,000 people, respectively). Chronic kidney disease was the second leading cause of the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous females (6.5% of the gap), and was the sixth leading cause for males (4.0%).

- 1,063 Indigenous Australians started kidney replacement therapy in 2019–2021, corresponding to a rate of 41 new cases of kidney failure with replacement therapy per 100,000 population. The incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy was 6 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians, based on age-standardised rates.

- As at 31 December 2021, there were 2,568 Indigenous and 24,774 non-Indigenous Australians receiving kidney replacement therapy (either dialysis, or a kidney transplant). Among Indigenous patients, 85% were on dialysis (2,170 of 2,568 patients), and 15% (398 of 2,568) had a functioning kidney transplant. In contrast, 51% (12,711 of 24,774) of non-Indigenous patients were on dialysis, and 49% (12,063 of 24,774 patients) had a functioning kidney transplant.

- Research shows that Indigenous patients with kidney failure are less likely to be wait-listed for transplantation than non-Indigenous Australians. Barriers to accessing kidney transplantation include systemic barriers such as service availability and likelihood of referral for transplant evaluation, cultural bias and individual patient factors such as co-morbidities which affect the acceptability of a kidney transplant.

- Reducing the chronic kidney disease burden for Indigenous Australians requires targeted interventions across the life course, starting before birth. A focus on the health and social determinants, improving primary prevention, early detection and better management of kidney disease is necessary.

Why is it important?

Kidneys are crucial to overall health, playing a vital role in cleaning the blood, removing waste and extra fluid from the body, managing Vitamin D production and regulating blood pressure (Kidney Health Australia 2020). The kidneys can be permanently damaged by various acute illnesses or by progressive damage from other chronic conditions, such as uncontrolled elevated blood pressure and longstanding high blood sugar levels (untreated or poorly managed diabetes).

If the kidneys cease functioning adequately (known as kidney failure or end-stage kidney disease), waste products and excess water build up rapidly in the body. This can cause death within a few days or weeks unless the patient undergoes dialysis, or a new kidney is provided by transplant. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are less likely to receive kidney transplants than non-Indigenous Australians, so many require dialysis for the rest of their lives, impacting quality of life and social and emotional wellbeing for patients and their carers (see measure 1.18 Social and emotional wellbeing) (Chadban et al. 2005; Devitt et al. 2008; Khanal et al. 2018; Rix et al. 2015).

CARI guidelines provide recommendations on clinical best practice for the management of chronic kidney disease in Australia and New Zealand, including care based on the best available evidence, and including specific recommendations for Indigenous Australians. As cited by Tunnicliffe et al. (2022) in Recommendations for culturally safe and clinical kidney care for First Nations Australians (Tunnicliffe DJ et al. 2022), research has shown that socioeconomic disadvantage leads to worse kidney function (Ritte et al. 2020) and higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease among Indigenous Australians (Cass et al. 2001).The relatively high burden of chronic kidney disease among Indigenous Australians reflects this social gradient in which those at the greatest disadvantage experience the highest incidence, prevalence, and impacts of disease (Marmot 2006; Morton et al. 2016).

Kidney disease can also contribute to, or be impacted by, chronic diseases including cardiovascular (circulatory) disease and diabetes (AIHW 2016). Cardiovascular disease, diabetes and kidney disease share a number of common risk factors such as tobacco smoking, overweight and obesity, and high blood pressure. Indigenous Australians have higher levels of risk factors associated with chronic diseases and are at a greater risk of developing chronic kidney disease, particularly those in remote areas. In many cases chronic kidney disease is preventable, as several key risk factors are modifiable (AIHW 2011).

Current guidelines recommend that an annual Kidney Health Check to identify chronic kidney disease should be included in the Medicare Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Health Assessment for those aged 18 years and over. Indigenous Australians under 18 years of age should be screened for potential risk factors for chronic kidney disease and then have a Kidney Health Check if needed (Tunnicliffe DJ et al. 2022). Ensuring all components of the publicly subsidised Kidney Health Check are undertaken at least annually, (including a urine albumin: creatinine ratio (ACR) test among Indigenous Australians at risk of chronic kidney disease), may increase early identification of chronic kidney disease. Screening for chronic kidney disease conditions can and should occur outside of a Medicare Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Health Assessment according to the need of Indigenous Australians.

Kidney disease is considerably more likely to be recorded as an additional diagnosis than as the principal diagnosis in hospital separations. In 2020–21, across Australia, there were around 58,200 hospitalisations (excluding dialysis) where chronic kidney disease was listed as the principal diagnosis and a further 333,000 hospitalisations where chronic kidney disease was listed as an additional diagnosis. Similarly, kidney disease is much more likely to be recorded on death certificates as an associated cause of death rather than as the underlying cause (AIHW 2023). There is also evidence that it may be under-reported as a cause of death, with a study using linked data from Western Australia and New South Wales showing that substantial proportions of people hospitalised with or receiving treatment for kidney failure do not have kidney failure recorded on their death certificate (AIHW 2014a; Sypek MP 2018). Looking only at the principal diagnosis or underlying cause of death therefore under-represents the true impact of chronic kidney disease. Therefore, this measure also includes data about kidney disease as an additional diagnosis or an associated cause of death.

Burden of disease

Burden of disease analysis is a way of measuring the impact of both living with poor health (the non-fatal burden of disease) and dying prematurely (fatal burden). It is measured using ‘disability-adjusted life years’ (DALY), where 1 DALY represents 1 year of healthy life lost, either through premature death (‘years of life lost’ or YLL) or from living with an illness or injury (‘years lived with disability’ or YLD).

Among all Indigenous Australians in 2018, chronic kidney disease accounted for:

- 2.5% (6,067 DALY) of the total Indigenous disease burden (239,942 DALY)

- 3.9% (4,416 YLL) of the total Indigenous fatal burden (premature death) (113,445 YLL), and

- 1.3% (1,651 YLD) of the total Indigenous non-fatal burden (years lived in ill health or with disability) (126,496) (AIHW 2022b).

In 2018, of the total burden attributable to chronic kidney disease (6,067 DALY) for Indigenous Australians, almost three-quarters (73% or 4,416 YLL) was fatal and just over one-quarter (27% or 1,651 YLD) was non-fatal.

After adjusting for differences in the age-structure between the two populations, the rate of burden due to chronic kidney disease for Indigenous Australians was 8 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (13 and 1.7 DALY per 1,000 people, respectively). Based on age-standardised rates, chronic kidney disease was the second leading cause of the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous females (6.5% of the gap), and was the sixth leading cause for males (4.0%).

These results exclude the indirect effects of chronic kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease is a risk factor for other diseases such as coronary heart disease, stroke, and dementia and the indirect burden is not accounted for using this approach.

Indirect effects of chronic kidney disease can be estimated in some cases by considering impaired kidney function as a risk factor for other diseases. In 2018, impaired kidney function was estimated to account for 5.0% of the total disease burden for Indigenous Australians, 8.4% of the fatal burden and 1.9% of the non-fatal burden (AIHW 2022b).

Data findings

Death rates for kidney diseases

Deaths data in this measure are from five jurisdictions for which the quality of Indigenous identification in the deaths data is considered to be adequate; namely, New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory. Data by remoteness are reported for all Australian states and territories combined (see Data sources: National Mortality Database).

Kidney disease can be listed as an underlying cause of death, or more commonly, as an associated causes (where another condition is listed on the death certificate as the underlying cause). In 2015–2019, there were 2,805 deaths among Indigenous Australians where kidney diseases was listed as the underlying or associated cause of death, meaning that in this period kidney disease contributed to almost one-fifth (18%) of all Indigenous deaths (Table D1.23.24). Considering both underlying and associated causes of death, the rate of deaths related to kidney diseases was 2.8 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.23.24).

Based on underlying cause of death, in the period 2015–2019, there were 279 deaths of Indigenous Australians that were due to kidney disease (including acute and chronic kidney disease), corresponding to a rate of 7.8 deaths per 100,000 population. Kidney diseases accounted for 1.8% of Indigenous deaths and 58% of kidney disease deaths were attributable to Indigenous females.

In 2015–2019, based on underlying cause of death:

- The rate of deaths due to kidney disease was higher for Indigenous females than Indigenous males (9.1 compared with 6.5 per 100,000, respectively).

- The death rate due to kidney diseases for Indigenous Australians was highest in the Northern Territory (17 per 100,000) and lowest in New South Wales (4.1 per 100,000).

- The rate of deaths due to kidney disease among Indigenous Australians in Remote and very remote areas combined was 2.7 times the rate in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner and Outer regional areas) (Table D1.23.2, Table D1.23.24, Table D1.23.30).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, based on underlying cause of death, deaths due to kidney diseases for Indigenous Australians were 2.3 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D1.10.4).

Hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease

Between July 2017 and June 2019, there were 474,745 hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians for care of chronic kidney disease involving dialysis, corresponding to a rate of 286 hospitalisations per 1,000 population (crude rate). Dialysis, which is used to treat kidney failure, was the leading cause of hospitalisation for Indigenous Australians (44% of hospitalisations).

Excluding dialysis, there were 6,710 hospitalisations for Indigenous Australians due to chronic kidney disease – or 4.0 hospitalisations per 1,000 population (crude rate).

After adjusting for differences in the age structure of the two populations:

- The rate of hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease that involved dialysis was 11 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians (age-standardised rates of 453 and 42 hospitalisations per 1,000 population, respectively).

- The rate of hospitalisation for chronic kidney disease, excluding dialysis, was 3 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians (age-standardised rates of 5.3 and 1.7 per 1,000 population, respectively) (Table D1.10.5).

By age group, between July 2017 and June 2019, the hospitalisation rate for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) among Indigenous Australians was highest for Indigenous Australians aged 55–64 (11 hospitalisations per 1,000 population). For non-Indigenous Australians, rates were highest for those aged 65 and over (4.5 per 1,000) (Table D1.10.6). Rates were higher for Indigenous females (5.4 per 1,000) than for Indigenous males (2.7 per 1,000) (crude rates) (Table D1.10.5).

For Indigenous Australians, across states and territories, the hospitalisation rate for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) was lowest in Tasmania (crude rate of 1.0 per 1,000), and highest in the Northern Territory (9.3 per 1,000). Across remoteness areas, the hospitalisation rate for chronic kidney disease among Indigenous Australians was lowest in Major cities and Inner regional areas (2.8 and 2.5 per 1,000 respectively), and increased with increasing remoteness, with the highest rate in Very remote areas (8.8 per 1,000) (Table D1.10.7, Table D1.10.8).

When chronic kidney disease, excluding dialysis, is considered as either the principal or an additional diagnosis, the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for Indigenous Australians in 2018–19 was 5 times that for non-Indigenous Australians, with the difference being greater for females than for males (rate ratios of 6.6 and 3.6, respectively) (Table D1.10.21).

For additional statistics and information relating to the broader Australian context on kidney disease, please see Chronic Kidney Disease: Australian Facts.

Kidney failure with replacement therapy

Kidney failure (also known as end-stage kidney disease) is the most severe form of chronic kidney disease. It occurs when the kidneys can no longer function adequately on their own. People living with kidney failure require either a kidney transplant or dialysis to maintain the functions normally performed by the kidneys. These treatments are collectively known as ‘kidney replacement therapy’. Note that not all people with kidney failure choose to undergo kidney replacement therapy. Instead, some opt to receive comprehensive conservative care, which focusses on patient care, quality of life and symptom control rather than on efforts to prolong life (AIHW 2023).

An estimate of the incidence of kidney replacement therapy can be obtained from the Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry (ANZDATA Registry). This registry includes information on people who have had kidney replacement therapy in the form of dialysis (peritoneal or haemodialysis) or a kidney transplant. It does not contain information on people with kidney failure who do not receive replacement therapy.

During the period 2019–2021, 1,063 Indigenous Australians with kidney failure started kidney replacement therapy – an average of nearly one person a day. This corresponds to an incidence rate of 41 new cases of kidney failure with replacement therapy for every 100,000 Indigenous Australians. The incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy was higher for Indigenous females than for Indigenous males (44 per 100,000 compared with 38 per 100,000) (Table D1.10.11).

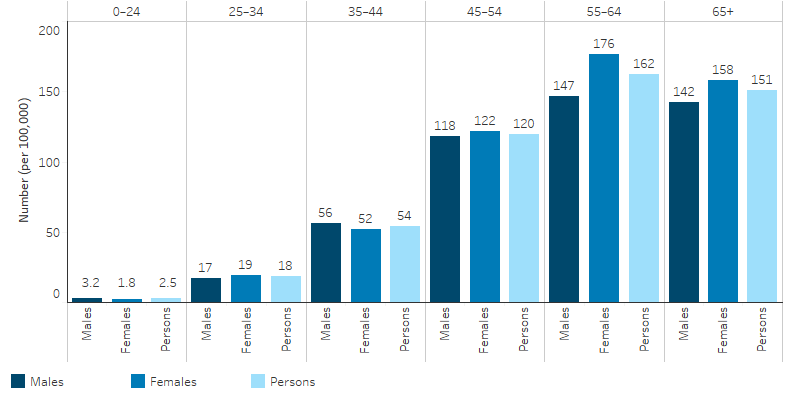

For both Indigenous males and females, the incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy generally increased with age and was highest for those aged 55–64. Among Indigenous Australians, rates were higher for females than males in most age groups, the exception being those aged 0–24 and 35–44, where rates were higher for Indigenous males (3.2 compared with 1.8 per 100,000 and 56 compared with 52 per 100,000, respectively) (Table D1.10.10, Figure 1.10.1).

The incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy was 6 times as high for Indigenous Australians as for non-Indigenous Australians (63 compared with 10 per 100,000 population, based on age-standardised rates) (Table D1.10.10).

Figure 1.10.1: Incidence (new cases) of kidney failure with replacement therapy, Indigenous Australians, by sex and age group, 2019–2021

Source: Table D1.10.10. AIHW analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

Across states and territories, for the period 2019–2021, the incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy among Indigenous Australians ranged from 12 new cases per 100,000 population in Victoria/Tasmania combined and New South Wales/Australian Capital Territory combined to 129 per 100,000 population in the Northern Territory (Table D1.10.11, Table 1.10-1).

Table 1.10-1: Incidence (new cases) of kidney failure with replacement therapy, Indigenous Australians, by sex and jurisdiction, 2019–2021

|

Jurisdiction |

Male number |

Male rate (per 100,000) |

Female number |

Female rate (per 100,000) |

Persons number |

Persons rate (per 100,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

NSW/ACT |

64 |

14.5 |

44 |

10.0 |

108 |

12.2 |

|

Vic/Tas |

19 |

13.4 |

15 |

10.7 |

34 |

12.0 |

|

Qld |

146 |

40.5 |

159 |

43.6 |

305 |

42 |

|

WA |

126 |

77.4 |

121 |

74.7 |

247 |

76.1 |

|

SA |

32 |

47.2 |

36 |

52.1 |

68 |

49.7 |

|

NT |

103 |

87.1 |

198 |

173.0 |

301 |

129.4 |

|

Australia |

490 |

37.9 |

573 |

44.3 |

1063 |

41.1 |

Source: Table D1.10.11. AIHW analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

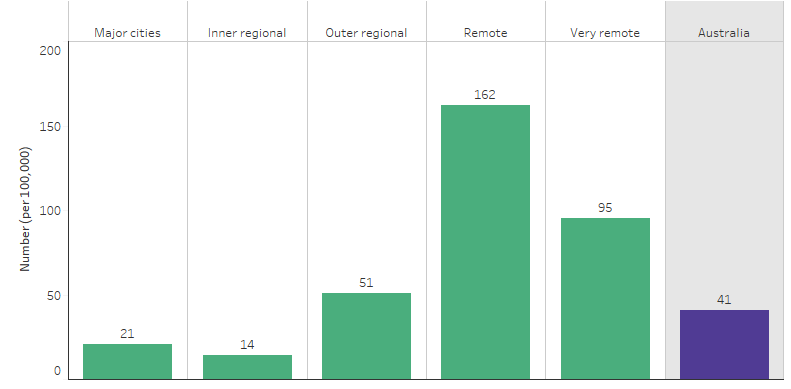

Of the 1,063 new cases of kidney failure among Indigenous Australians who had started replacement therapy in 2019–2021, one-quarter (260 or 25%) lived in Remote areas of Australia, a similar proportion to Outer regional (248 or 24%) and Very remote (272 or 26%) areas. Taking account of population size of Indigenous Australians in different remoteness areas, the incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy for Indigenous Australians was highest among those who lived in Remote areas, with 162 new cases per 100,000 population and was lowest for those who lived in Inner regional areas, with a rate of 14 per 100,000 population. (Table D1.10.12, Figure 1.10.2).

Figure 1.10.2: Incidence (new cases) rates of kidney failure with replacement therapy, Indigenous Australians, by remoteness, 2019–2021

Source: Table D1.10.12. AIHW analysis of Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

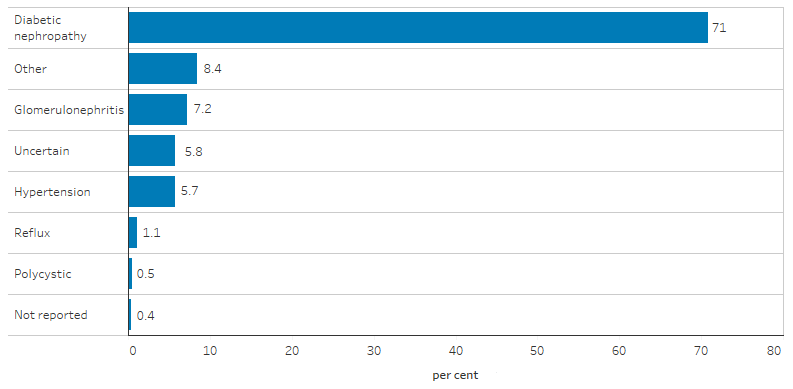

In 2019–2021, among Indigenous Australians receiving kidney replacement therapy, the most common type of primary kidney disease was diabetic kidney disease (also known as diabetic nephropathy), which represents 71% (753) of the new 1,063 Indigenous kidney replacement therapy patients. This was followed by glomerulonephritis (77 or 7.2%) and hypertension (61 or 5.7%) (Table D1.10.18, Figure 1.10.3).

Figure 1.10.3: Primary kidney disease of new Indigenous kidney replacement therapy patients, 2019–2021

Source: Table D1.10.18. AIHW analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

As at 31 December 2021, there was a total of 2,568 Indigenous Australians with kidney failure who were receiving kidney replacement therapy, a prevalence (existing cases) rate of 289 per 100,000 population. Of these cases:

- 2,170 (85%) who were reliant on dialysis; and

- 398 (15%) had a functioning kidney transplant (that is, living with a successful kidney transplant, regardless of how long ago they received it) (Table D1.10-2).

Among people receiving kidney replacement therapy, Indigenous Australians were less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to receive a kidney transplant. Among non-Indigenous Australians receiving kidney replacement therapy, 49% (12,063 of 24,774 patients) had a functioning kidney transplant, compared with 15% of Indigenous Australians (Table D1.10-2).

Table 1.10-2: Total patients with kidney failure receiving replacement therapy, by Indigenous status and treatment, 31 December 2021

|

Treatment |

Indigenous number |

Non-Indigenous number |

Indigenous % |

Non-Indigenous % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dialysis |

2,170 |

12,711 |

84.5 |

51.3 |

|

Transplant |

398 |

12,063 |

15.5 |

48.7 |

|

Total |

2,568 |

24,774 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

Source: Table D1.10.14. AIHW analysis of Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

Based on 2020 data, the majority (74%) of Indigenous Australians receiving replacement therapy were treated with facility-based haemodialysis. The remaining 26% were able to access care closer to home – 5% were accessing community house or at home haemodialysis, 6% were utilising peritoneal dialysis and 15% had received a transplant (ANZDATA Registry 2021).

In the 6-year period 2016–2021, 1,381 Indigenous Australians were reliant on dialysis to manage their kidney failure at the time of their death. The primary cause of death in over one-third (466 deaths or 34%) of these cases was due to cardiovascular diseases, a further one-fifth (307 deaths or 22%) was due to withdrawal from dialysis and 12% (161 deaths) was due to infections. Among Indigenous Australians who received a transplant to manage their kidney failure, there were 49 deaths in 2016–2021 – the leading cause of these deaths was cardiovascular disease (13 deaths or 27%), followed by cancer (7 deaths or 14%), infections, and withdrawal (both 6 deaths or 12%) (Table D1.10.17).

Findings from ABS survey data

Due to the asymptomatic nature of chronic kidney disease, and because diagnosis requires the presence of measured biomedical markers that persist for at least 3 months, people often do not realise they have the disease. As a result, numbers based on self-report are often underestimates of the true number of people living with chronic kidney disease in Australia. Accurate estimates of the prevalence require large-scale surveys of biomedical markers of kidney function in the population.

The 2012–13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (AATSIHS) is the most recent national survey to include biomedical testing of markers for chronic kidney disease among Indigenous Australians. Based on the 2012–13 AATSIHS, nearly 1 in 5 (18%) Indigenous Australian adults had blood/urine test results showing signs of chronic kidney disease. Chronic kidney disease is classified into 5 stages, depending on the level of kidney function. In 2012–13:

- 12% of Indigenous adults had biomedical signs of chronic kidney disease in the earliest stage (stage 1), and 3.3% in stage 2. In this stage there are usually no symptoms.

- 1.7% of Indigenous adults had biomedical signs of stage 3 chronic kidney disease.

- 1.1% of Indigenous adults had biomedical signs of stage 4 or 5 chronic kidney disease.

In the 2012–13 AATSIHS, only 11% of those with signs of chronic kidney disease reported having the condition, indicating that majority of Indigenous Australians with chronic kidney disease don’t realise they have it (ABS 2014). Note however that the point-in-time tests used to identify signs of chronic kidney disease cannot alone provide a diagnosis, and could indicate the presence of an acute kidney condition or infection instead. Kidney disease can only be confirmed if indicators are persistent for at least three months.

Based on the self-reported data from the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), 3.4% of Indigenous adults reported having chronic kidney disease, 3 times the rate of non-Indigenous adults (1.1%), after adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations.

The self-reported rate of chronic kidney disease for Indigenous Australians increased with age, from 0.1% for those aged 18–24, to 7.6% for those aged 55 and over. The rates for non-Indigenous Australians followed a similar pattern with rates increasing from 0.5% for those aged 25–34, to 2.5% for those aged 55 and over.

Indigenous Australians living in remote areas were 2.3 times as likely as those living in non-remote areas to self-report having chronic kidney disease (6.4% and 2.8%, respectively) (Table D1.10.1).

In 2018–19, Indigenous adults who rated their health as fair/poor were 3 times as likely to report having kidney disease compared with those rating their health as excellent/very good/good (5.8% compared with 1.7%). Indigenous adults who reported having diabetes were 5 times as likely to report having kidney disease compared with those without diabetes (9.2% compared with 1.7%). Indigenous adults reporting cardiovascular problems were 8 times as likely to report having kidney disease compared with those without cardiovascular problems (8.1% compared with 1.0%). Indigenous Australians who were obese were twice as likely to report having kidney disease compared with those who were underweight/normal weight (3.8% compared with 1.9%) (Table D1.10.2).

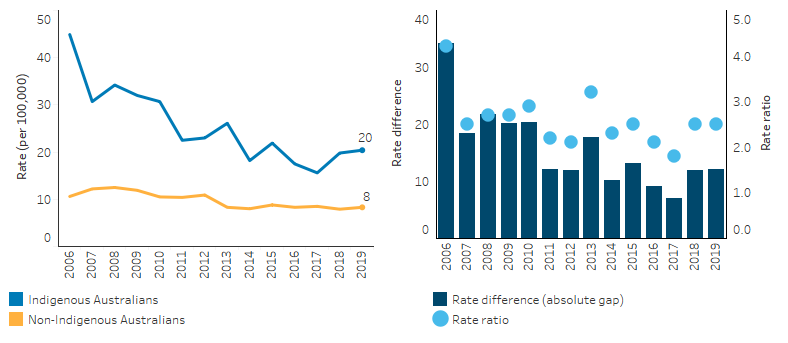

Change over time

Over the decade from 2010 to 2019, the age-standardised death rate due to kidney diseases (including acute and chronic conditions) as the underlying cause of death generally trended downwards, ranging between 30.7 deaths per 100,000 population (in 2010) and 15.6 deaths per 100,000 in 2017. Using linear regression to assess the overall trend, the age-standardised rate declined by 36% for Indigenous Australians and 26% for non-Indigenous Australians. However, the gap in the rates for the two populations did not change significantly over this period (Table D1.23.23, Figure 1.10.4).

Over a longer period, between 2006 and 2019, the age-standardised death rate due to kidney disease among Indigenous Australians decreased by 60%, compared with a 37% decrease for non-Indigenous Australians (based on linear regression). The absolute gap (rate difference) between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians ranged between 7.0 in 2017, and 34.2 in 2006. Using linear regression to assess the trend, the gap (rate difference) narrowed by 71% between 2006 and 2019 (Table D1.23.23, Figure 1.10.4).

Figure 1.10.4: Age-standardised death rates and changes in the gap due to kidney diseases, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006 to 2019

Note: Rate difference is the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for Indigenous Australians minus the age-standardised rate (per 100,000) for non-Indigenous Australians. Rate ratio is the age-standardised rate for Indigenous Australians divided by the age-standardised rate for non-Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D1.23.23. AIHW analysis of National Mortality Database.

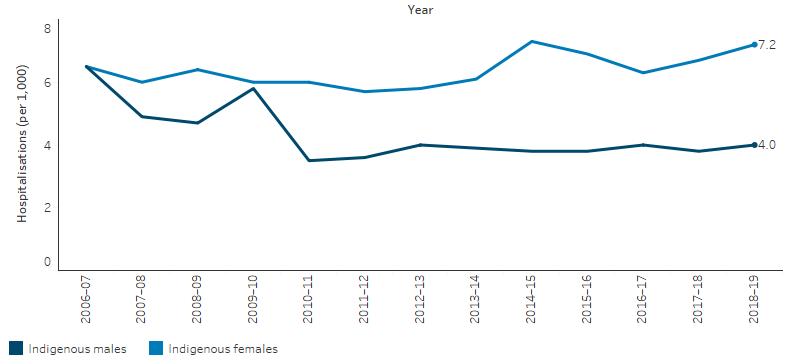

For hospitalisation trends, six jurisdictions are considered to have Indigenous identification of an adequate quality over the period 2006–07 to 2018–19 (New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory). In these jurisdictions, between 2006–07 and 2018–19, the age-standardised hospitalisation rate for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) among Indigenous Australians decreased by 8% (based on linear regression). However, this varied by sex, with a 36% decline among Indigenous males but an increase of 14% among females.

Between 2009–10 and 2018–19, based on age-standardised rates, there was an overall 6% increase in hospitalisation rates for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis), with a 16% reduction among Indigenous males and a 22% increase among Indigenous females (Table D1.10.20, Figure 1.10.5).

Among non-Indigenous Australians, the age-standardised rate of hospitalisations for chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) increased by 23% over the decade to 2018–19, with increases for both males (18%) and females (29%). The gap was similar in 2009–10 as in 2018–19 (Table D1.10.20).

Figure 1.10.5: Age-standardised hospitalisation rates for a principal diagnosis of chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis) for Indigenous Australians, by sex, NSW, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2006–07 to 2018–19

Source: Table D1.10.20 AIHW analysis of National Hospital Morbidity Database

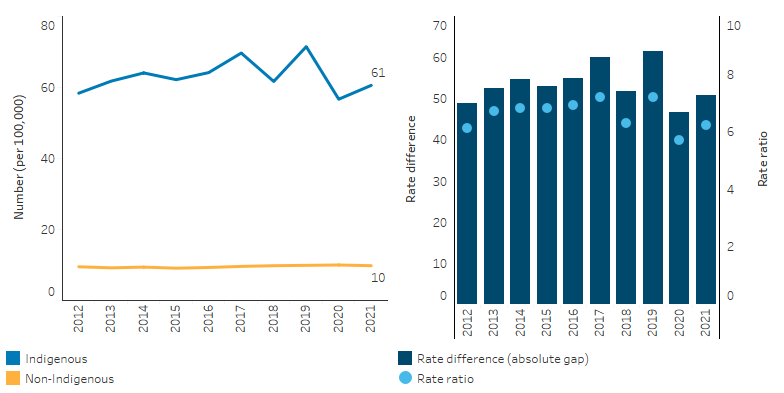

For Indigenous Australians, over the decade from 2012 to 2021, data from the ANZDATA Registry shows that:

- The crude incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy increased by 20% for males, but was unchanged for Indigenous females (Table D1.10.13).

- The crude incidence rate increased by 53% in Queensland, declined by 37% in New South Wales but remained unchanged for other jurisdictions (Table D1.10.15).

- The total prevalence of kidney failure with replacement therapy has increased from a rate of 223 per 100,000 to 291 per 100,000 (Table D1.10.16).

Based on age-standardised rates, there weren't any significant changes in the incidence of kidney failure with replacement therapy for Indigenous Australians, nor any significant changes in the gap. (Table D1.10.13, Figure 1.10.6).

Figure 1.10.6: Age-standardised incidence rates of kidney failure with replacement therapy and changes in the gap, by Indigenous status, 2012 to 2021

Source: Table D1.10.13. AIHW analysis of the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry.

Research and evaluation findings

A significant amount of research has gone towards understanding the antecedents of kidney disease among Indigenous Australians, particularly in remote areas. The National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT) reported that kidney failure is a serious and increasingly common health problem in Australia. Indigenous Australians, especially those who live in remote communities, have a much greater risk of developing kidney failure and requiring dialysis treatment, but their likelihood of receiving a kidney transplant is substantially lower than that of non-Indigenous patients. The findings suggest that current models of care are inadequate and lack a specific focus on the Indigenous patient population, particularly for those from rural and remote areas (Garrard et al. 2019).

Reviews of the literature have highlighted that kidney disease is multi-determinant, with risk factors including nutritional and developmental disadvantage, low birthweight, childhood infections, family history of kidney disease, as well as adult onset chronic diseases such as hypertension, and diabetes (Hoy 2014; Stumpers & Thomson 2013). Modifiable risk factors also exist including tobacco smoking, overweight and obesity, and insufficient physical activity (AIHW 2023). A review by the Australian Indigenous HealthInfoNet identified that addressing social determinants of health is key to preventing kidney disease among Indigenous Australians (Schwartzkopff et al. 2020).

Kidney health care is also logistically difficult, with challenges associated with diagnosing and treating kidney disease in remote Australia. Research shows that barriers in remote areas include not only accessing treatment, but also accessing appropriate information and education (Garrard et al. 2019). Flow-on effects from this include significant disruption to wellbeing, disempowerment and disconnection with communities from being away, and reveals challenges within the health care system in terms of cultural competency and equity (Hoy 2014; Stumpers & Thomson 2013).

Indigenous patients with kidney failure are less likely to be wait-listed for transplantation than non-Indigenous Australians (Khanal et al. 2018). The health system may pose barriers to accessing transplantation for Indigenous Australians such as reduced likelihood of referral for transplant evaluation; lack of comprehensive investigation of Indigenous patients; and communication and education limitations. There may also be individual patient factors that pose barriers such as incompatibility, higher rates of co-morbidities which affect the acceptability of a kidney transplant, and lower compliance to medical treatment as a result of communication problems, cultural bias, and a range of other factors (Kelly et al. 2020; Stumpers & Thomson 2013). Geographic factors may also act as a barrier to transplantation, with research showing that Indigenous patients are not only less likely to be waitlisted for a transplant, but that this disparity increases with remoteness (Garrard et al. 2019; Khanal et al. 2018).

A study of Australian nephrologists (specialists of kidney disease) found that, in the absence of robust evidence on predictors of post-transplant outcomes, decisions on which patients to refer for kidney transplants were influenced by factors such as kidney shortages, compliance with dialysis as a predictor of compliance with transplant regimes (despite large differences in these factors), and experiences with other Indigenous patients (Anderson et al. 2012). Some of these issues are based on miscommunication between health care provider and patient, and a lack of appropriate patient education. This may lead to generalisations about the patient’s circumstances and therefore result in a bias towards considering Indigenous patients as high risk. Recognising and responding to these cultural differences appropriately will be crucial to improving the management of Indigenous patients. A more systematic approach to monitoring compliance to dialysis and transplant treatment for Indigenous patients will help in basing referral decisions on evidence (Anderson et al. 2012; Garrard et al. 2019; Kelly et al. 2020).

A cohort study of people who received their first kidney transplant between 2005 and 2018 in Australia, using data from the Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant registry, found that Indigenous Australians experienced around a 2-fold risk of allograft loss and a 3-fold risk of infection-related death compared with non-Indigenous Australians (Zheng et al. 2022). The study findings indicated that acute rejection partially mediated the relationship between Indigenous status and graft loss, and therefore modifying the risk of acute rejection could prevent a proportion of allograft loss among Indigenous Australians. However, the association between risk of infection-related death and Indigenous status was found to be independent of acute rejection. The authors suggest various social and structural determinants may contribute to the disparity in survival, and note that pathways between Indigenous status, graft loss and death are likely complex and multifactorial.

High rates of Indigenous Australians in remote areas requiring dialysis leads to patients leaving their homes, communities and country to visit dialysis services in non-remote areas. Research found that almost one quarter (23.9%) of Australian kidney replacement therapy patients between 2005 and 2015 relocated, with patients relocating more frequently and earlier from outer regional, remote and very remote areas towards major cities and inner regional areas (Hassan et al. 2020).This disruption affects the health and wellbeing of patients. Dialysis services in remote Australia have been expanding through providers such as the Purple House.

The South Australian Mobile Dialysis Truck allows patients to have dialysis closer to home for one- to two-week periods. An evaluation of the South Australian program found it improved the social and emotional wellbeing of patients by allowing them to fulfil cultural commitments and improved patient quality of life, as well as build positive relationships and trust between metropolitan nurses and remote patients. The Truck may also serve to improve cultural competency of health staff (Conway et al. 2018) (for more information see measure 2.13 Transport). Importantly, however, by providing short term care, mobile dialysis trucks such as those provided by the South Australian Government and also the Purple House do not improve relocation rates in the long term. To ensure Indigenous Australians can remain connected to Country, fixed dialysis infrastructure, like the sites run by Purple House are required.

A review of kidney health among Indigenous Australians provided general information on the historical, social and cultural context of kidney health, and the behavioural factors that contribute to kidney disease. It discussed the prevention and management of kidney health problems, and provided information on relevant programs, services, policies and strategies that address kidney disease among Indigenous Australians. It concludes by discussing possible future directions for kidney health for Indigenous people in Australia (Schwartzkopff et al. 2020).

Implications

Kidney disease represents a major challenge for patients and the health system. In 2018–19, an estimated $1.8 billion of expenditure in the Australian health system was attributed to chronic kidney disease, representing a total of 1.3% of the total disease expenditure. Of this, 1.6 billion (89% of the total expenditure for chronic kidney disease) was spent on hospital services: $1 billion on admitted patient care in public hospitals, $330 million on admitted patient care in private hospitals, and $180 million on public hospital outpatient care (AIHW 2023).

Reducing the chronic kidney disease burden for Indigenous Australians requires targeted interventions across the life course, starting before birth (Cass 2019). In alignment with the Closing the Gap targets and the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021-2031 (the Health Plan) objectives, a focus on the social determinants of health, improving primary prevention, early detection and better management of kidney disease is necessary to lessen the impact on patients, and to reduce the cost to the health care system. Strategies could include more patient education and better management of modifiable risk factors such as controlling blood pressure, controlling high blood sugar levels, quitting smoking, maintaining a healthy diet and being physically active. From 1 September 2022, the Australian Government expanded the PBS listing of clinical indications for use of the drug treatment dapagliflozin to improve or maintain kidney function independent of diabetic control, and help reduce the risk of progressive decline in kidney function.

Mainstream service providers and specialists need to be culturally safe to better help Indigenous Australians, particularly from remote areas, to navigate the kidney disease continuum. The CARI guidelines: Recommendations for Culturally Safe and Clinical Kidney Care for First Nations Australians recommend that institutional racism could be addressed through actively decolonising services by starting with increasing self-determination and empowerment of patients, families, and communities that need to engage with mainstream kidney health services (Tunnicliffe DJ et al. 2022).

Despite improved availability of services, disparities between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in receiving kidney transplants remain. This may be a reflection of flow-on effects of Indigenous patients from remote areas undergoing dialysis which result in barriers to transplantation assessment, as well as factors such as cultural differences and communication issues within the health care system. Reducing the disruption experienced by patients relocating for dialysis treatment may in turn improve clinical assessment for transplantation which may then improve the access of Indigenous patients to kidney transplantation (Khanal et al. 2018). For patients on dialysis, innovative use of mobile dialysis treatment can provide short term respite for patients closer to home to help maintain cultural obligations and connection to family and country, it may also improve the cultural competency of health care staff. However, providers note significant challenges with mobile dialysis and a hesitancy to recommend this as a long-term solution.

Purple House provides culturally safe dialysis and support across remote Australia, providing dialysis in 19 remote communities and operating two mobile dialysis units (the Purple Truck). In 2023, the Australian Government announced new kidney dialysis units in six remote locations, ensuring Indigenous Australians with severe kidney diseases can receive lifesaving treatment closer to their communities. This expansion is in recognition that Indigenous Australians in remote areas often travel hundreds of kilometres to access dialysis, making treatment difficult to maintain and resulting in poor health outcomes.

Improving the inequitable burden of kidney disease that is experienced by Indigenous Australians is an achievable goal. Genuine and committed partnerships between the Australian governments, healthcare providers and Indigenous Australians are imperative to maximize the success of health equity initiatives (Hughes 2021).

The Health Plan, released in December 2021, recognises early access to responsive primary care is also key to addressing the higher hospitalisation rates of Indigenous Australians, where presentation often occurs at a later stage of disease and can lead to higher rates of mortality. The Health Plan emphasises that action to address cardiovascular disease, diabetes, ear, eye and renal (kidney) health, and rheumatic heart disease, remain key priorities.

The Health Plan includes a long-term vision to eliminate racism, with immediate action to address racism across the health system. An improved health system that is culturally safe and responsive to the needs of Indigenous Australians aligns to Priority Reform 3 of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap which aims to transform government organisations to work better for Indigenous Australians.

A significant body of work over the past two decades has sought to raise awareness and embed concepts of cultural respect in the Australian health system which are fundamental to improving access to quality and effective health care and improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. There has been a longstanding commitment by Australian governments to enable this. The Cultural Respect Framework 2016–2026 plays a key role in reaffirming this commitment and provides a nationally consistent approach (AHMAC 2017). The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework plays a role in monitoring this commitment across several measures (see measure 3.08 Cultural competency). Monitoring is also supported by the Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework which covers three domains: how health-care services are provided, Indigenous patients’ experience of health care, and measures regarding access to health care (AIHW 2022a). The 2022 cultural safety report showed that a commitment to achieving culturally safe health care by Indigenous-specific health care organisations was 95% in 2017-18, an increase from 86% in 2012-13, while noting the lack of data available for reporting on the policies and practices of mainstream health services (AIHW 2022a). This lack of data presents a challenge to ensuring the availability of culturally safe and effective health services for Indigenous Australians.

The National Strategic Action Plan for Kidney Disease includes Objective 2.4 to reduce the disproportionate burden of kidney disease on Indigenous Australians, and assisting NIKTT in its work to improve access to, and outcomes of, kidney transplantation for Indigenous Australians (Kidney Health Australia 2019).

Various forms of racism and cultural bias have been identified as barriers to Indigenous Australians receiving equitable access to kidney transplantation. The NIKTT was established in 2019 to improve access to, and improve post-transplant outcomes from, kidney transplantation for Indigenous Australians (Kelly et al. 2020). The NIKTT was tasked with responsibilities for implementing and evaluating the recommendations outlined in a comprehensive review into the hurdles, service gaps and practical challenges faced by Indigenous Australians receiving treatment for kidney disease (The Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand). Key objectives of the NIKTT include enhancing data collection and reporting, piloting initiatives to improve patient equity and access, and evaluating cultural bias interventions (National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce 2020).

Other progress includes the finalisation of a scoping review that outlines priority recommendations to inform future activities that can help address cultural bias in service delivery for kidney transplantation for Indigenous Australians (Kelly et al. 2020). The review identified four key domains of action (each with several recommendations) to address cultural bias in kidney transplantation for Indigenous Australians: Inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people; Workforce; Service delivery approach and models of care; and Structures and policies. The review emphasises the importance of co-designed and co-created participative approaches to research, implementation and evaluation for the development of new models of transplantation care for Indigenous Australians living with kidney disease (Kelly et al. 2020).

Having better integrated data collections can expand the knowledge base for guiding health policy and funding activities, and can help improve understanding of the joint role of diseases in causing death (AIHW 2012, 2014b). A fuller capture of deaths for which kidney disease is an associated cause of death, rather than limited to the underlying cause of death, would help provide a greater understanding of the burden of Indigenous kidney disease that is not currently well understood, which in turn will help policy development (Hoy et al. 2020).

The policy context is at Policies and Strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2014. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Biomedical Results 2012–13. Cat. no. 4727.0.55.003. Canberra: AIHW.

- AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council) 2017. Cultural Respect Framework 2016-2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Vol. 17 (ed., Council of Australian Governments). Canberra: AHMAC.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011 Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2012. Multiple causes of death An analysis of all natural and selected chronic disease causes of death 1997-2007. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014a. Assessment of the coding of ESKD in deaths and hospitalisation data: a working paper using linked hospitalisation and deaths data from Western Australia and New South Wales. Cat. no. PHE 182. (ed., AIHW). Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014b. Assessment of the coding of ESKD in deaths and hospitalisation data: a working paper. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2016. Diabetes and chronic kidney disease as risks for other diseases: Australian Burden of Disease Study 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed October 2022.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2023. Chronic kidney disease: Australian facts. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Viewed 29/09/2022.

- Anderson K, Devitt J, Cunningham J, Preece C, Jardine M & Cass A 2012. If you can't comply with dialysis, how do you expect me to trust you with transplantation? Australian nephrologists' views on indigenous Australians' 'non-compliance' and their suitability for kidney transplantation. International Journal for Equity in Health 11:21.

- ANZDATA Registry 2021. Kidney Failure in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry 44.

- Cass A 2019. Kidney disease in indigenous populations. Darwin: Menzies School of Health Research.

- Cass A, Cunningham J, Wang Z & Hoy W 2001. Social disadvantage and variation in the incidence of end-stage renal disease in Australian capital cities. Aust N Z J Public Health 25:322-6.

- Chadban S, McDonald S, Excell L, Livingstone B & Shtangey V 2005. Twenty Eighth Report: Australia and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry 2005. (ed., Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing with Kidney Health Australia & New Zealand Ministry of Health). Adelaide: ANZDATA Registry.

- Conway J, Lawn S, Crail S & McDonald S 2018. Indigenous patient experiences of returning to country: a qualitative evaluation on the Country Health SA Dialysis bus. BMC health services research 18:1010.

- Devitt J, Cass A, Cunningham J, Preece C, Anderson K & Snelling P 2008. Study Protocol--Improving Access to Kidney Transplants (IMPAKT): a detailed account of a qualitative study investigating barriers to transplant for Australian Indigenous people with end-stage kidney disease. BMC health services research 8:31.

- Garrard E, McDonald S, Gorham G, Rohit A & Triggs C 2019. Improving Access to and Outcomes of Kidney Transplantation for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People in Australia: Performance Report. The Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand.

- Hassan HIC, Chen JH & Murali K 2020. Incidence and factors associated with geographical relocation in patients receiving renal replacement therapy. BMC nephrology 21:1-8.

- Hoy WE 2014. Kidney disease in Aboriginal Australians: a perspective from the Northern Territory. Clinical kidney journal 7:524-30.

- Hoy WE, Mott SA & McDonald SP 2020. An update on chronic kidney disease in Aboriginal Australians. Clinical nephrology 93:124-8.

- Hughes JT 2021. Kidney health equity for Indigenous Australians: an achievable goal. Nature Reviews Nephrology 17:505-.

- Kelly J, Dent P, Owen K, Schwartzkopff K & O’Donnell K 2020. Cultural bias Indigenous kidney care and kidney transplantation report. Lowitja Institute.

- Khanal N, Lawton PD, Cass A & McDonald SP 2018. Disparity of access to kidney transplantation by Indigenous and non‐Indigenous Australians. Medical Journal of Australia 209:261-6.

- Kidney Health Australia 2019. National Strategic Action Plan for Kidney Disease.

- Kidney Health Australia 2020. Know your Kidneys. Viewed September 2020.

- Levey AS, Eckardt KU, Dorman NM, Christiansen SL, Hoorn EJ, Ingelfinger JR et al. 2020. Nomenclature for kidney function and disease: report of a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Consensus Conference. Kidney Int 97:1117-29.

- Marmot MG 2006. Status syndrome: a challenge to medicine. JAMA 295:1304-7.

- Morton RL, Schlackow I, Mihaylova B, Staplin ND, Gray A & Cass A 2016. The impact of social disadvantage in moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease: an equity-focused systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31:46-56.

- National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce 2020. Performance Report February 2020 Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand.

- Ritte RE, Lawton P, Hughes JT, Barzi F, Brown A, Mills P et al. 2020. Chronic kidney disease and socio-economic status: a cross sectional study. Ethn Health 25:93-109.

- Rix EF, Barclay L, Stirling J, Tong A & Wilson S 2015. The perspectives of Aboriginal patients and their health care providers on improving the quality of hemodialysis services: A qualitative study. Hemodialysis International: International Symposium on Home Hemodialysis 19:80-9.

- Schwartzkopff K, Kelly J & Potter C 2020. Review of kidney health among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 20.

- Stumpers SA & Thomson NJ 2013. Review of kidney disease among Indigenous people.

- Sypek MP DK, Clayton P, Webster AC & McDonald S 2018. Comparison of cause of death between Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry and the Australian National Death Index. Nephrology 24:322-9.

- The Transplantation Society of Australia and New Zealand. National Indigenous Kidney Transplantation Taskforce (NIKTT).

- Tunnicliffe DJ, Bateman S, Arnold-Chamney M, Dwyer KM, Howell M, Jesudason S et al. 2022. Recommendations for culturally safeand clinical kidney care for First Nations Australians. Sydney, Australia: Caring for Australian and New zealanders with Kidney Impairment.

- Zheng C, Teixeira-Pinto A, Hughes JT, Sinka V, van Zwieten A, Lim WH et al. 2022. Acute Rejection, Overall Graft Loss, and Infection-related Deaths After Kidney Transplantation in Indigenous Australians. Kidney Int Rep 7:2495-504.