Key facts

Why is it important?

Cultural competency and related concepts are ways of mediating some of the harmful effects of colonisation and its continuing impacts (including discrimination and racism) on the health and health care of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Improving the cultural competency of health care service providers can increase Indigenous Australians’ access to health care, increase the effectiveness of the care that is received, and improve disparities in health outcomes (Freeman et al. 2014). The accessibility of a health service goes beyond its physical availability and also encompasses other aspects such as whether it is culturally safe (Scrimgeour & Scrimgeour 2008). The provision of culturally safe care is essential to meet the health care needs of Indigenous Australians effectively, and requires health professionals to have considered power relations, cultural differences and patients’ rights (AHMAC 2017). ‘Cultural competency requires that organisations have a defined set of values and principles, and demonstrate behaviours, attitudes, policies and structures that enable them to work effectively cross-culturally’ (Dudgeon et al. 2010). Cultural competency has two primary drivers—sociocultural differences and health care disparities (Jongen et al. 2018b).

In recent years there has been a focus on moving people and organisations beyond cultural awareness and towards achieving cultural respect (AHMAC 2017). Building the capacity of the non-Indigenous workforce to achieve this requires appropriate, high quality professional development and training; capability in organisations to manage staff who demonstrate a lack of cultural respect; and for staff to develop an awareness of unconscious bias they may have through self-reflection on their own cultural biases. In addition to cultural competency, other concepts used to support action on cultural respect include cultural safety and cultural security. Cultural respect is achieved when the health system is accessible, responsive and provides a safe environment for Indigenous Australians, where cultural values, strengths and differences are respected. A significant body of work over the past two decades has sought to raise awareness and embed concepts of cultural respect in the Australian health system that are fundamental to improving access to quality and effective health care and improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians. There has been a longstanding commitment by Australian governments to enable this. The Cultural Respect Framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health 2016–2026: A National Approach to Building a Culturally Respectful Health System plays a key role in reaffirming this commitment and provides a nationally consistent approach (AHMAC 2017). It is the second framework developed to help resolve issues related to cultural respect in the Australian health care system. The framework outlines six domains that underpin culturally respectful health service delivery: whole of organisation approach and leadership; communication; workforce development and training; consumer participation and engagement; stakeholder partnerships and collaboration; and data, planning, research and evaluation. The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF) plays a role in monitoring the commitment to embed cultural respect principles into the Australian health system.

Monitoring is also supported by the Cultural Safety in Health Care for Indigenous Australians: Monitoring Framework which covers three domains: how health care services are provided, Indigenous patients’ experience of health care, and measures regarding access to health care (AIHW 2019a).

There is increasing recognition that improving cultural safety for Indigenous Australians can improve access to, and the quality of health care. This means a health system in which Indigenous cultural values, strengths and differences are respected; and racism and inequality are addressed.

Cultural competency and related concepts can be measured directly (self-reporting on patient experience) or indirectly (for example discharge against medical advice, employment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers). However, there is limited data available on the cultural competency of health services (Paradies et al. 2014) and on the effectiveness of interventions to address cultural competency in health care for Indigenous Australians (Clifford et al. 2015; Truong et al. 2014). In particular, there remains a lack of data reporting on the policies and practices of mainstream health services (AIHW 2019a).

Many Indigenous primary health care organisations have a strong history of providing culturally competent health care. In 2017–18 more than two-thirds (71%) of Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations were Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) (AIHW 2019b). The findings below include information on the systems that Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations have in place to ensure cultural competency which serve as useful examples for building cultural competency in mainstream health services.

Data findings

Monitoring and measuring cultural respect in the health system nationally is difficult. In this performance measure we have drawn from a range of national data collections which provide various perspectives from Indigenous Australians on their experiences of the Australian health system.

Self-reported survey data

In the 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (Health Survey), 23% (116,200) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported that they had been treated unfairly in the previous 12 months because they were Indigenous. A further 70% (349,800) reported that they had not been treated unfairly in the last 12 months because they were Indigenous. Please note, those who did not know if they had been treated unfairly have not been reported on here, but were included when calculating these proportions.

Around 14% (69,700) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported that they avoided situations in the previous 12 months due to past unfair treatment. Of those who reported they avoided certain situations as a result of unfair treatment, 13% (8,900) had avoided seeking health care (Table D3.08.17).

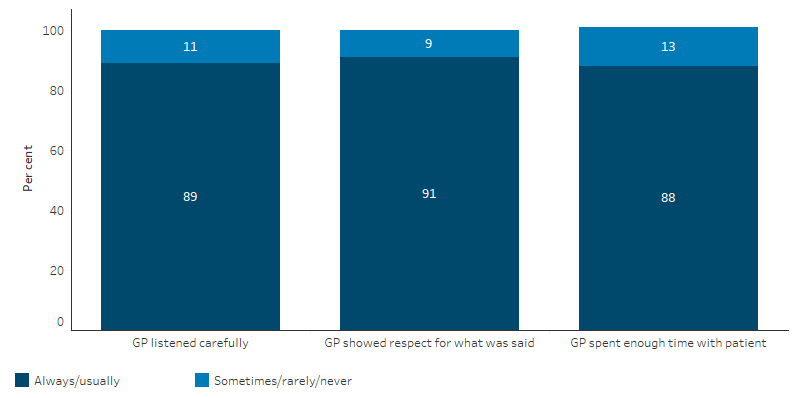

In 2018–19, most Indigenous Australians who had seen a doctor in the last 12 months reported that their general practitioner (GP) always/usually showed respect for what was said (91%, or 312,700), listened carefully to them (89%, or 305,200) or spent enough time with them (88%, or 300,800) (Table D3.08.21, Figure 3.08.1). In 2014–15, while most Indigenous Australians had positive interactions with doctors, a small proportion (6%, or 28,400) disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement ‘Your doctor can be trusted’ (Table D3.08.20).

National data for all Australians from the Patient Experience Survey 2018–19 showed that GPs always or often listened carefully (92%), showed respect (94%) and spent enough time with their patients (90%) (ABS 2019).

Figure 3.08.1: Patient experience in the last 12 months, Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, 2018–19

Source: Table D3.08.21. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

In 2014–15, of the estimated 46,700 (11%) Indigenous Australians reporting they mainly spoke an Indigenous language, 38% (17,700) reported having difficulty understanding or being understood in places where only English is spoken (Table D3.08.15).

The 2018–19 Health Survey showed that 75% (257,300) of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over in Non-remote areas gave excellent or very good as the overall rating of the health care they received in the last 12 months (Table D3.08.6).

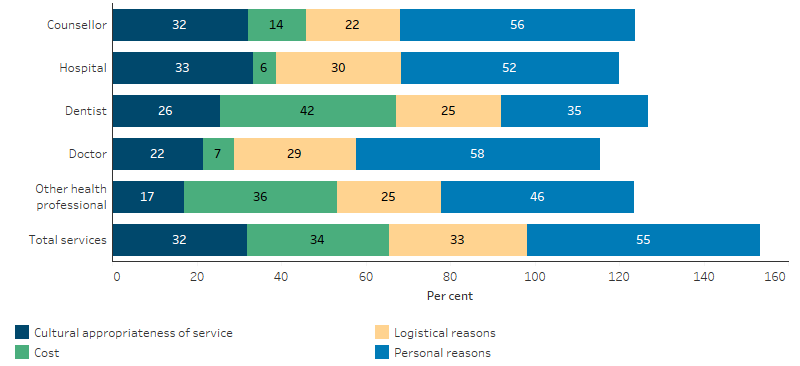

An estimated 30% (243,400) of Indigenous Australians reported that they did not access health care when they needed to in the past 12 months. Of those who did not access health care when needed, the reasons relating to cultural appropriateness of service were (more than one response was allowed):

- dislikes service/professional, embarrassed, afraid (23%)

- felt it would be inadequate (9%)

- does not trust service/provider (7%)

- discrimination/not culturally appropriate/language problems (2.6%) (Table D3.08.3, Table 3.08-1).

Other reasons Indigenous Australians reported for why they did not access health care when needed were cost (34%), logistical reasons (33%) and personal reasons (55%). Reasons do not total 100% as more than one response was allowed (Table D3.08.3, Figure 3.08.2).

Table 3.08-1: Indigenous Australians who did not access health services when needed to, and the reasons relating to cultural appropriateness, 2018–19

|

Reason(s) did not access service |

Dentist |

Doctor |

Other health professional |

Hospital |

Counsellor |

Total health services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Discrimination/ not culturally appropriate/ language problems |

0.8%† |

1.4%† |

1.1%‡ |

4.7%† |

4.1%† |

2.6% |

|

Dislikes service/professional, embarrassed, afraid |

21.8% |

11.4% |

10.8% |

17.4% |

12.6% |

23.0% |

|

Felt it would be inadequate |

1.4%† |

9.5% |

5.2%† |

12.1% |

13.6% |

8.8% |

|

Does not trust service provider |

2.9% |

4.1% |

2.9%† |

11.5% |

6.7%† |

7.4% |

|

Cultural appropriateness of service (subtotal) |

25.6% |

21.5% |

17.1% |

33.4% |

32.3% |

32.0% |

|

Did not access service when needed to in last 12 months |

18.9% |

12.5% |

9.0% |

6.2% |

9.6% |

29.9% |

† Estimate has a relative standard error between 25% and 50% and should be used with caution.

‡ Estimate has a relative standard error greater than 50% and is considered too unreliable for general use.

Source: Table D3.08.3.

In 2018–19, among Indigenous Australians who did not access care when it was needed, reasons reported relating to the cultural appropriateness of services were highest for hospitals (33%), followed by counsellors (32%), dentists (26%) and doctors (22%). Cost (42%) and dislike of service/professional or felt embarrassed/afraid (22%) were major barriers to accessing dental services, which has links to poor oral health outcomes (Table D3.08.3, Figure 3.08.2).

Figure 3.08.2: Reasons Indigenous Australians did not access health services when needed to, 2018‑19

Note: more than one response allowed, sum exceeds 100%.

Source: Table D3.08.3. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

Hospitalisation

An indirect measure of cultural safety is the rate of discharge from hospital against medical advice. While reasons for leaving against medical advice may be varied and complex, such a measure can indicate the extent to which hospitals are responsive to the needs of Indigenous patients.

The rate of discharge against medical advice or at own risk provides indirect evidence of the extent to which hospital services are culturally competent and responsive to Indigenous patients’ needs. Between July 2015 and June 2017, there were 19,915 hospitalisations where Indigenous Australians left against medical advice or were discharged at their own risk. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, this represented 3.1% of all Indigenous hospitalisations, compared with 0.5% for non-Indigenous Australians (Table D3.09.1). For more information, see measure 3.09 Self-discharge from hospital.

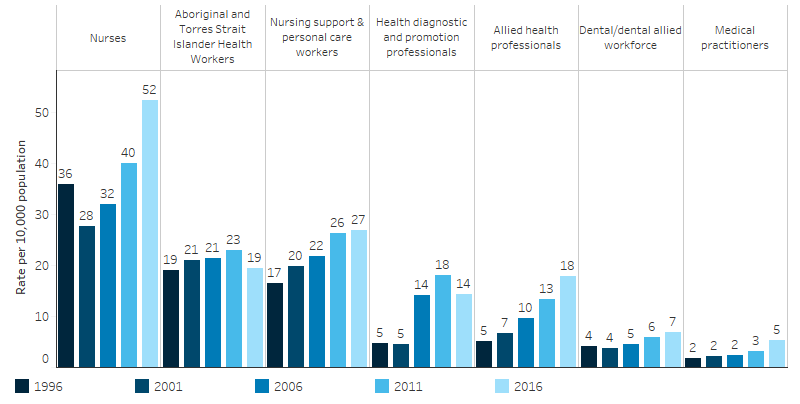

Employed health practitioners

In 2016, there were 11,161 Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over employed in health-related occupations. Nursing (3,383) was the largest group followed by nursing support and personal care workers (1,731), and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers (1,253). Between 1996 and 2016 the rate of Indigenous Australians employed in the health workforce increased from 96 to 173 per 10,000 (see measure 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce) (Table D3.12.12, Figure 3.08.3).

Figure 3.08.3: Employed Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over, by health‑related occupation, Australia, 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016

Source: Table D3.12.12, AIHW and ABS analysis of Census of Population and Housing.

Indigenous primary health care organisations

At 30 June 2018, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Practitioners represented 13% of all full-time equivalent (FTE) positions within Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations (Table D3.22.11). In 2017–18, just over half (54%) of the FTE paid positions in Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations were occupied by Indigenous Australians (Table D3.12.15).

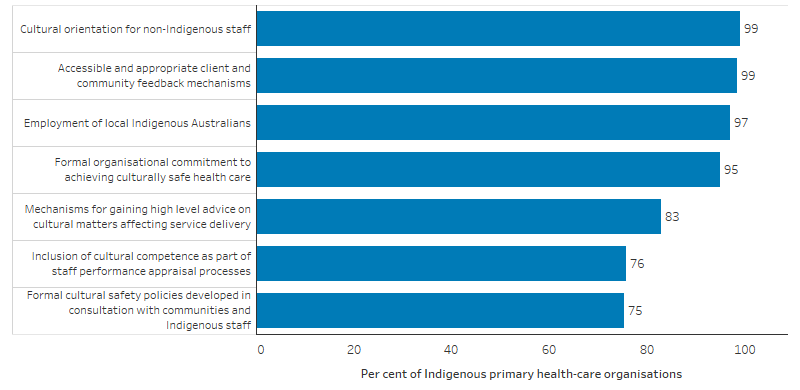

In 2017–18, of the 156 Indigenous primary health care organisations who had a governing committee or board, 69% had a governing committee or board with all Indigenous members (Table D3.13.3). Of Indigenous primary health care organisations with cultural safety policies or processes in place, 99% provided cultural orientation for non-Indigenous staff, 99% had appropriate client or community feedback mechanisms, 97% employed local Indigenous Australians, 95% had a formal commitment to achieving culturally safe health care, and 83% had mechanisms for gaining high-level advice on cultural matters affecting service delivery (Table D3.08.14, Figure 3.08.4).

Figure 3.08.4: Proportion of Indigenous primary health care organisations with cultural safety policies or processes in place, 2017‑18

Source: Table D3.08.14. AIHW analyses of Online Services Report data collection 2017–18.

In 2017–18, cultural group activities (for example, art, hunting, or bush outings) were provided by 51% of the 198 Indigenous primary health care organisations; and by 75% of Indigenous organisations funded to provide substance-use treatment for Indigenous Australians (Table D3.03.10, Table D3.03.11). Of the primary health care organisations, 40% provided interpreting services, 21% offered traditional healing, 19% offered bush tucker nutrition programs and 19% offered bush medicine (Table D3.08.25).

Research and evaluation findings

Effective communication is the foundation for the delivery of accessible, responsive and safe health care (AHMAC 2017). Finlay and Wenitong (2020) discussed the important role of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) during the COVID-19 pandemic, when clear, concise, culturally appropriate health communication is vital for Indigenous Australians who are at increased risk from COVID‐19 (Finlay & Wenitong). The study notes that ACCHSs have demonstrated their capacity to deliver scientifically valid, evidence‐based and culturally appropriate disease prevention messages, and that communications have been produced in addition to usual service delivery while using existing funding.

The communication gap between health professionals and Indigenous Australians has a significant effect on health outcomes, and is most pronounced in remote areas where cultural and linguistic differences are greatest. There is an urgent need to pay more attention to the communication needs of remote Indigenous Australians, but this is not taught in medical education (Amery 2017). Recommended communication strategies include greater use of interpreters, using diagrams and illustrations, using plain English, demonstrating procedures first, allowing extra time for Indigenous patients to respond, and looking for culturally meaningful analogies.

A systematic review of the literature on teaching cultural competence in dental education and its relevance for the oral health care of Indigenous Australians found that students need knowledge of health disparities to better understand the perspectives of, and to communicate effectively with, culturally diverse populations (Forsyth et al. 2017). The most effective strategies were educational seminars, community service-learning and reflective writing.

In its first audit of institutional racism, the Health Performance Council of South Australia assessed nine of the ten South Australian Local Health Networks (LHN) as having very high evidence of institutional racism, with the tenth LHN assessed as being in the moderate range (Health Performance Council 2020). The audit recommended that institutional racism could be ameliorated in the LHNs in a number of ways, including by providing culturally safe and appropriate health care services in accordance with nationally agreed health system performance standards.

A study of 755 Indigenous adults in Victoria found 30% had experienced racism in health settings in the previous 12 months (Kelaher et al. 2014). In a qualitative evidence review, Gomersall and others (2017) found that there was often a lack of respect and no shared understanding between primary health care providers and Indigenous clients in mainstream services, or among clients (Gomersall et al. 2017). In contrast, relationships in ACCHSs were characterised by respect and understanding.

An evaluation of the Victorian government’s Koolin Balit investment showed improvements in cultural responsiveness and cultural safety for Indigenous Australians in some Victorian hospitals (Social Compass 2017).

A qualitative study of the cultural appropriateness of primary health care services provided to Indigenous Australians living in a remote North West Queensland community found that a significant number of the 54 Indigenous patients interviewed did not consider the services they were receiving to be culturally appropriate, in contrast to the views of the primary health care providers, who perceived their communication with Indigenous patients to be clear and understandable (Smith et al. 2017). There was however, alignment between Indigenous patients and the primary health care providers on perceptions that patients received a high level of respect and support from providers.

When services are designed specifically for and with Indigenous Australians, improved outcomes are achievable (Gwynne et al. 2019). A review of the evidence showed that ACCHSs contribute to improving the health and wellbeing of Indigenous Australians by providing accessible, comprehensive primary health care (Campbell et al. 2018). Studies have shown that ACCHS programs have improved access and use of a range of services such as antenatal care, cardiac and respiratory rehabilitation programs, mental health, eye care and dental care. A private GP practice in Queensland found that by working in partnership with the Indigenous community the number of Indigenous patients increased from 5 to 40 per month (Johanson & Hill 2011). Strategies introduced included bulk billing, one session per week specifically for Indigenous patients and a bus to the clinic. In addition, cultural safety training was undertaken by staff and an Indigenous health worker attended the clinic to assist with cultural safety and referrals.

A small study measuring the effect of a community of practice on the self-assessed cultural competency and change to the practice of 13 dieticians working in Indigenous health found that formalised and structured Communities of Practice may be an effective workforce development strategy, with participants describing increased competence through networking and joint problem solving (Elvidge et al. 2019). The participants described increased confidence in their work through improved understanding of the factors related to the effect of history, culture and use of resources on service delivery, appropriate communication strategies, effective relationships and managing conflict.

A qualitative study of the Aboriginal Maternity Group Practice Program that started in Perth in 2011 surveyed 16 program clients and 22 individuals from partner organisations, and interviewed 15 staff (Bertilone et al. 2017). The program employed Indigenous staff in a partnership model working with local maternity services. The study found that this program contributed to the provision of a culturally competent service, particularly in hospitals, and providing transport, team home visits and employing Indigenous staff improved access to care.

A review of evaluations of cultural competency interventions in health care for Indigenous peoples and other minority culturally and linguistically diverse groups in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United States (CANZUS) found heterogeneity in workforce intervention strategies, measures and outcomes (Jongen et al. 2018a). The two main intervention strategies were cultural competency training and professional development interventions such as mentoring. While positive outcomes were frequently reported for health practitioners’ knowledge and attitudes, there was limited evidence of the impact on health care and outcomes. Another review of evaluations and measures of cultural competency interventions in CANZUS nations noted that there is strong advocacy for systems-level approaches to cultural competence, but the primary focus in the literature remains on strategies aimed at health promotion initiatives, workforce development and student education (McCalman et al. 2017). The fundamental principles for implementing systems approaches were user engagement, organisational readiness and delivery across multiple sites. The primary types of strategies were audit and quality improvement approaches and service-level policies or strategies. Gaps identified were a need for cost and effectiveness studies of systems approaches and an explanation of the impact on client experience.

A Western Australian report on cancer care (Thompson M. et al. 2011a) made several practical recommendations to improve the cultural competency of care for Indigenous patients including: providing a welcoming environment through welcome to country services, yarning places and access to traditional foods; facilitating the return of Indigenous patients to their homelands for continued care where possible; ensuring that there is access to Indigenous language interpreters for Indigenous people who are not confident speakers of English, ensuring that staff understand differences in Indigenous verbal and non-verbal communication styles; and ensuring service providers are familiar with, acknowledge and respect Indigenous family structures, culture and life circumstances.

Elvidge and others (2019) developed a survey and scale to measure cultural safety in New South Wales hospitals from an Indigenous patient perspective (Elvidge et al. 2019). The survey covered five domains: positive communication between patients and hospital staff; negative communication; trust between patients and hospital staff; the hospital environment; and support for Indigenous families and culture. The validity and reliability of this tool was tested on 316 participants who had attended a New South Wales hospital in the past 12 months. Testing demonstrated a high level of content and construct validity, and the Cultural Safety Survey Scale has potential as a tool for hospitals to measure the cultural safety of their services, and whether efforts to improve cultural safety are resulting in Indigenous patients reporting more culturally safe experiences.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers play an important role in improving cultural competency in health care delivery (Thompson S. et al. 2011b). Conway and others (2017) discussed the vital role of Aboriginal Health Workers in better chronic disease management via culturally appropriate support and knowledge sharing with clients (Conway et al. 2017). A small study in the cardiology unit of a Western Australian hospital found these health workers improved the cultural safety of the care provided, and their positive impacts included facilitating culturally appropriate care, bridging communication divides, reducing the number of discharges against medical advice, providing cultural education and increasing participation in cardiac rehabilitation through increased patient contact time and follow-up (Taylor et al. 2009). Strategies to reduce discharge against medical advice from hospitals include the development of more flexible community-based care models to provide culturally appropriate care (Shaw 2016).

Shared medical appointments are ‘comprehensive medical visits run with groups of participating patients’ and have been shown to improve access to primary health care for Indigenous Australians (Stevens et al. 2016). A study in New South Wales showed these are an effective way to improve patient experience after seeing an increase in attendance over time among Indigenous male patients who attended shared medical appointments with trained Aboriginal Health Workers (Stevens et al. 2016).

Harfield and others (2018) noted that Indigenous primary health care services evolved because of the inability of mainstream health services to adequately meet the needs of Indigenous communities, and the exclusion of Indigenous people from mainstream health services (Harfield. et al. 2018). This systematic review identified eight vital characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models—culture, accessible health services, community participation, continuous quality improvement, culturally appropriate and skilled workforce, flexible approach to care, holistic health care, and self-determination and empowerment.

A systematic review of health programs for Indigenous Australians enabling expression of cultural identity, which targeted diet, physical activity, birthing and antenatal care, and emotional wellbeing, identified improvements in psychosocial, behavioural and clinical measures (MacLean et al. 2017).

Implications

There remain significant gaps in the evidence on the cultural competency of health services in Australia, in particular for mainstream services. However the evidence available suggests that in 2018–19 30% of Indigenous Australians did not access health care when they needed to in the past 12 months. While there were a range of reasons for non-access, the reason was related to the cultural appropriateness of the service for around one-third of people who did not go to hospital or a counsellor, and around one-quarter of those who did not see a dentist or doctor. Elevated levels of discharge against medical advice suggest that there are significant issues in the responsiveness of hospitals to the needs and perceptions of Indigenous Australians, and there remains a disparity in accessibility and outcomes for hospital procedures between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (see measures 3.06 Access to hospital procedures and 3.09 Self-discharge from hospital).

Gomersall and others’ (2017) review of qualitative evidence recommended that mainstream practitioners seeking to improve the accessibility and quality of their care should invest in understanding Indigenous clients’ needs and learn how to be respectful of their culture; take a flexible and proactive approach, for example, meeting clients outside standard operating hours; and invest in creating a welcoming environment, such as by displaying posters representative of Indigenous culture in clinics (Gomersall et al. 2017). However, the authors cautioned that for many Indigenous Australians, the care provided by mainstream primary health care providers might not be a substitute for care provided by ACCHSs. Mainstream organisations can struggle to provide an appropriate service for a small minority of the population with specific needs. A review of chronic disease care programs operating in rural and remote ACCHSs found that a partnership between mainstream health services and ACCHSs is essential (Liaw et al. 2011).

The Lighthouse Hospital Project, funded through the Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme, and run by the Heart Foundation aims to drive systemic change in the acute care sector to change the way hospitals and health services are governed, organised, structured and staffed to address institutional racism and improve care and outcomes for Indigenous Australians who experience acute coronary syndrome (ACS) (Heart Foundation 2020; Verhoeven 2018). It is designed to improve governance, clinical quality, and cultural competence of the health workforce. Each hospital in the program receives the Lighthouse Toolkit, which includes a plan, action areas and quality improvements, and outlines ways hospitals can provide culturally appropriate and clinically competent care for Indigenous Australians and their families. In 2017, phase three expanded the project to 18 hospitals across Australia. Phase three evaluation of the project highlighted that more than three-quarters of Indigenous Australians with ACS surveyed in Lighthouse Hospitals rated their hospital experience as ‘very good’ or ‘good’.

To Indigenous Australians the term ‘health’ means not just the physical wellbeing of an individual, but refers to the social, emotional and cultural wellbeing of the whole community in which each individual can achieve their full potential as a human being, thereby bringing about the total wellbeing of their community. Culturally competent health services recognise this holistic concept of health, and Australian governments have focused on improving the cultural competency of health services.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013–2023 (NATSIHP) draws attention to ‘the centrality of culture in the health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and the rights of individuals to a safe, healthy and empowered life’ (DoHA 2013). Achieving improvements in health outcomes for Indigenous Australians means working towards fulfilling the vision of the NATSIHP—a health system that is free of racism and inequality and where all Indigenous Australians have access to health services that are effective, high quality, appropriate and affordable. Beginning in late 2020, the plan will undergo a refresh—to embed cultural and social determinants of health and provide a single, overarching policy framework for Indigenous health. More information on the NATSIHP is in Policies and strategies.

The development and delivery of well-designed and implemented cultural safety training programs can assist in the aim of achieving a health system that is a safe environment for Indigenous Australians and where cultural differences are respected. Health services should have the organisational culture, and adequate resources, to support cultural safety and responsiveness training of health staff at all levels and across all disciplines (AHMAC 2017). The cultural awareness training programs that are currently offered, however, could be improved (Aspin et al. 2012). Indigenous cultural awareness training tends to homogenise Indigenous cultures, and position them as distinct from the ‘norm’. An increased emphasis on reflexivity and self-awareness in training could assist health workers to better understand their own values and beliefs, and how they shape the care that they provide. It is acknowledged that cultural education needs to be ongoing, and localised to the region in which health-care providers are working (Kerrigan et al. 2020). However, there is a need for more research and evaluation of training programs to understand what works (Downing et al. 2011).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. Patient Experiences in Australia: Summary of Findings, 2018-19. Cat. no. 4839.0. Canberra: ABS.

- AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council) 2017. Cultural Respect Framework 2016-2026 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health. Canberra: AHMAC.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019a. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

- AIHW 2019b. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health organisations: Online Services Report — key results 2017–18. Canberra: AIHW.

- Amery R 2017. Recognising the communication gap in Indigenous health care. Medical Journal of Australia.

- Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, Yen L & Leeder S 2012. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC health services research 12:143.

- Bertilone CM, McEvoy SP, Gower D, Naylor N, Doyle J & Swift-Otero V 2017. Elements of cultural competence in an Australian Aboriginal maternity program. Women and Birth 30:121-8.

- Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

- Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R & Tsey K 2015. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: a systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 27:89-98.

- Conway J, Tsourtos G & Lawn S 2017. The barriers and facilitators that indigenous health workers experience in their workplace and communities in providing self-management support: a multiple case study. BMC health services research 17:319.

- DoHA (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing) 2013. National Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2013-2023. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Downing R, Kowal E & Paradies Y 2011. Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 23:247-57.

- Dudgeon P, Wright M & Coffin J 2010. Talking It and Walking It: Cultural Competence. Journal of Australian Indigenous Issues 13:29-44.

- Elvidge E, Paradies Y, Aldrich R & Holder C 2019. Cultural safety in hospitals: validating an empirical measurement tool to capture the Aboriginal patient experience. Australian Health Review 44:205-11.

- Finlay S & Wenitong M. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations are taking a leading role in COVID-19 health communication. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health n/a.

- Forsyth CJ, Irving MJ, Tennant M, Short SD & Gilroy JA 2017. Teaching cultural competence in dental education: a systematic review and exploration of implications for Indigenous populations in Australia. Journal of Dental Education 81:956-68.

- Freeman T, Edwards T, Baum F, Lawless A, Jolley G, Javanparast S et al. 2014. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: beyond education and training of practitioners. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 38:355-61.

- Gomersall JS, Gibson O, Dwyer J, O'Donnell K, Stephenson M, Carter D et al. 2017. What Indigenous Australian clients value about primary health care: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health.

- Gwynne K, Jeffries T & Lincoln M 2019. Improving the efficacy of healthcare services for Aboriginal Australians. Australian Health Review 43:314-22.

- Harfield. SG, Davy. C, McArthur. A, Munn. Z, Brown. A & Brown. N 2018. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systemic scoping review. Globalization and Health 14.

- Health Performance Council [South Australia] 2020. Institutional racism — Audit of South Australia’s Local Health Networks. Adelaide.

- Heart Foundation 2020. The Lighthouse Hospital Project: The story so far. Heart Foundation.

- Johanson RP & Hill P 2011. Indigenous health: A role for private general practice. Australian Family Physician 40.

- Jongen C, McCalman J & Bainbridge R 2018a. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC health services research 18:232.

- Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R & Clifford A 2018b. Cultural competence in health: A review of the evidence. Springer.

- Kelaher MA, Ferdinand AS & Paradies Y 2014. Experiencing racism in health care: The mental health impacts for Victorian Aboriginal communities. The Medical Journal of Australia 201:44-7.

- Kerrigan V, Lewis N, Cass A, Hefler M & Ralph AP 2020. “How can I do more?” Cultural awareness training for hospital-based healthcare providers working with high Aboriginal caseload. BMC Medical Education 20:1-11.

- Liaw ST, Lau P, Pyett P, Furler J, Burchill M, Rowley K et al. 2011. Successful chronic disease care for Aboriginal Australians requires cultural competence. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 35:238-48.

- MacLean S, Ritte R, Thorpe A, Ewen S & Arabena K 2017. Health and wellbeing outcomes of programs for Indigenous Australians that include strategies to enable the expression of cultural identities: a systematic review. Australian journal of primary health 23:309-18.

- McCalman J, Jongen C & Bainbridge R 2017. Organisational systems’ approaches to improving cultural competence in healthcare: a systematic scoping review of the literature. International Journal for Equity in Health 16:78.

- Paradies Y, Truong M & Priest N 2014. A systematic review of the extent and measurement of healthcare provider racism. Journal of General Internal Medicine 29:364-87.

- Scrimgeour M & Scrimgeour D 2008. Health care access for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living in urban areas, and related research issues: a review of the literature. Cooperative Research Centre for Aboriginal Health.

- Shaw C 2016. An evidence-based approach to reducing discharge against medical advice amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. Deakin, ACT: AHHA.

- Smith K, Fatima Y & Knight S 2017. Are primary healthcare services culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people? Findings from a remote community. Australian journal of primary health 23:236-42.

- Social Compass 2017. Evaluation of Improving Cultural Responsiveness of Victorian Hospitals Final Report. Melbourne: Government of Victoria.

- Stevens JA, Dixon J, Binns A, Morgan B, Richardson J & Egger G 2016. Shared medical appointments for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men. Australian Family Physician 45:425.

- Taylor KP, Thompson SC, Wood MM, Ali M & Dimer L 2009. Exploring the impact of an Aboriginal Health Worker on hospitalised Aboriginal experiences: lessons from cardiology. Australian Health Review 33:549-57.

- Thompson M, Robertson J & Clough A 2011a. A review of the barriers preventing Indigenous Health Workers delivering tobacco interventions to their communities. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 35.

- Thompson S, Shahid S, Greville H & Bessarab D 2011b. “A whispered sort of stuff” A community report on research around Aboriginal people’s beliefs about cancer and experiences of cancer care in Western Australia. Perth: Cancer Council

- Truong M, Paradies Y & Priest N 2014. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC health services research 14:99.

- Verhoeven A 2018. The Lighthouse Project Quality improvement to achieve lasting change in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander heart health. The Health Advocate.

Related measures

- 1.13 Community functioning

- 3.09 Self-discharge from hospital

- 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce

- 3.13 Competent governance

- 3.14 Access to services compared with need

- 3.17 Regular general practitioner or health service

- 3.20 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people training for health-related disciplines