Key messages

- Australia is one of the safest places in the world for a baby to be born. The rate at which perinatal death occurs reflects a number of factors, including the health status and health care of the general population, access to and quality of services for women, and health care in the neonatal period. Broader social factors such as maternal education, nutrition, smoking, alcohol use during pregnancy and socioeconomic factors are also important. Babies born to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) mothers have a higher rate of death during the perinatal period than babies born to non-Indigenous mothers.

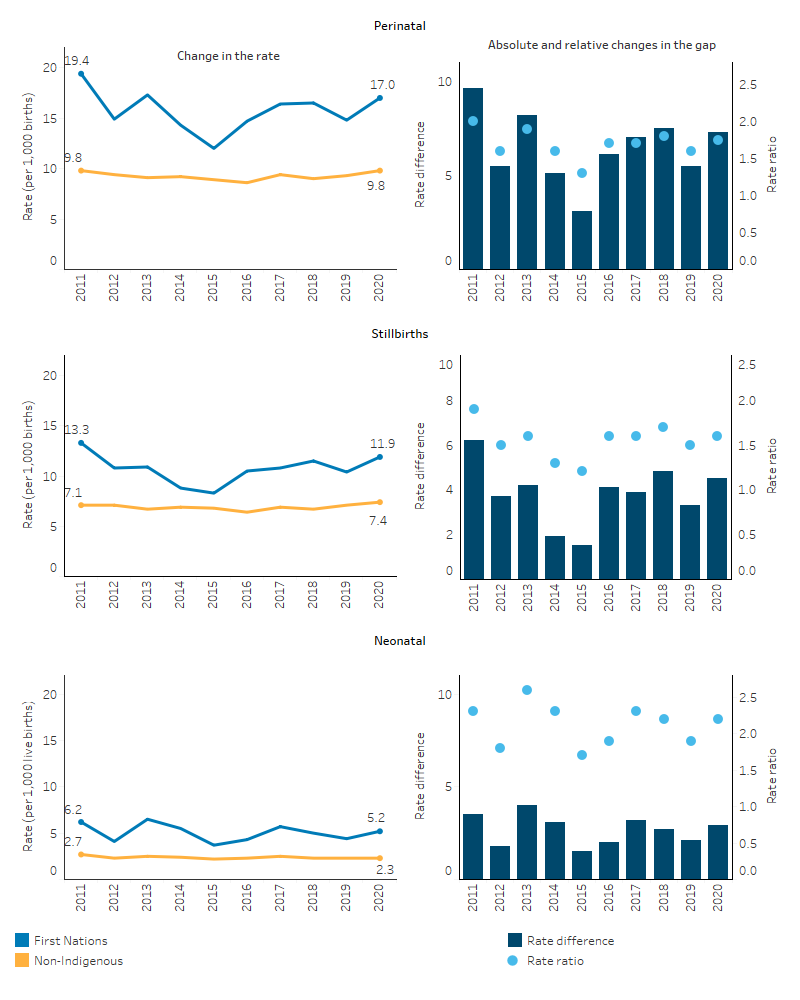

- Over the decade from 2011 to 2020, there was no significant change in the rate of perinatal, neonatal or stillbirth deaths among babies born to First Nations mothers. During the same period, the absolute gap in rates of perinatal, neonatal or stillbirth deaths between babies born to First Nations mothers or those born to non-Indigenous mothers did not change significantly.

- In 2013–2020, the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers was 1.7 times as high as for babies born to non-Indigenous mothers – 15.4 deaths compared with 9.2 deaths per 1,000 births.

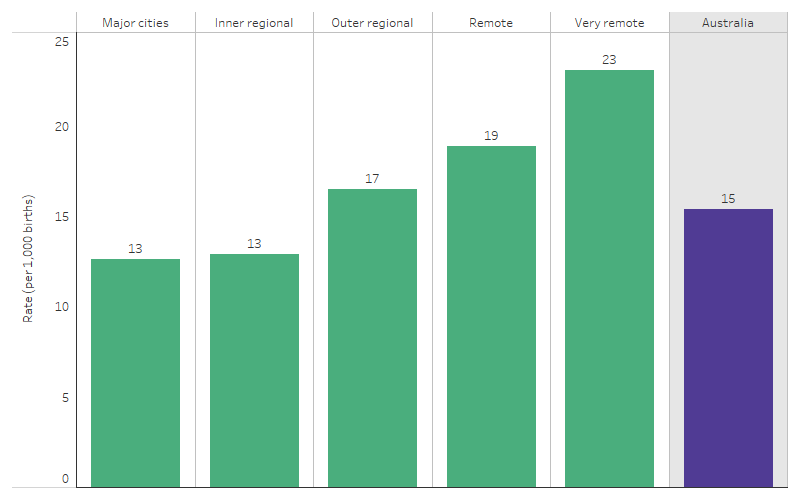

- In 2013–2020, the rate of perinatal deaths for babies born to First Nations mothers was higher in more remote areas, ranging from 13 per 1,000 in Major cities and Inner regional areas to 23 per 1,000 in Very remote areas.

- In the period 2013–2020, the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers was highest for those living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas of Australia (17 deaths per 1,000 births) but was similar across all other socioeconomic quintiles (around 14 deaths per 1,000 births).

- Across states and territories, in the period 2015–2019, the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers ranged from 24.2 perinatal deaths per 1,000 births in the Northern Territory to 9.5 per 1,000 in Tasmania.

- A study among First Nations mothers in Townsville showed that sustained access to community-based, integrated, shared antenatal services significantly reduced the perinatal death rate compared with a control group (60 compared with 14 deaths per 1,000 births).

- Smoking during pregnancy is one of the main contributing factors to a range of poor perinatal outcomes including low birthweight, pre-term birth and perinatal death.

Why is it important?

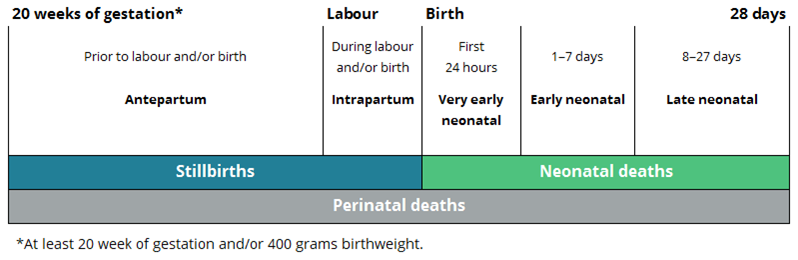

Perinatal deaths are those occurring prior to or during labour and/or birth (stillbirth) or up to 28 days after birth (neonatal death) where the baby is of 20 or more completed weeks of gestation or with a birthweight of at least 400 grams (AIHW 2021a) (Figure 1.21.1). Most of these deaths are due to factors that occur during pregnancy and childbirth. Perinatal mortality reflects the health status and health care of the general population, access to and quality of preconception, reproductive, antenatal, and obstetric services for women, and health care in the neonatal period. Broader social factors such as maternal education, nutrition, smoking, alcohol use during pregnancy and socioeconomic disadvantage are also important (Eades 2004; Performance Indicator Reporting Committee 2002).

Providing culturally safe continuity of care and addressing risk factors (see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy); supporting attendance at antenatal care (see measure 3.01 Antenatal care); addressing maternal nutritional status; illness during pregnancy; pre-existing high blood pressure and diabetes; and socioeconomic disadvantage, can lead to improved outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) women and babies (ABS & AIHW 2008; AIHW 2011; Brown et al. 2016; Eades et al. 2008; Khalidi et al. 2012; Sayers & Powers 1997). Women who are healthy before and during pregnancy have a better chance of having a healthy baby (see measure 1.01 Birthweight).

Babies born to First Nations mothers have higher rates of perinatal mortality (both stillbirth and neonatal death) than babies born to non-Indigenous mothers. First Nations mothers also experience key risk factors for perinatal mortality at higher rates than non-Indigenous mothers. Significant policy attention by Australian and state and territory governments aim to address these disparities. However, over the decade 2011 to 2020, there has been no significant change in the rates of stillbirths or neonatal death among babies born to First Nations mothers.

In recognition of the disparities in rates of stillbirth for First Nations women, the National Stillbirth Action and Implementation Plan (Department of Health 2020) has a focus on ensuring culturally safe stillbirth prevention and care for First Nations women (Action area 2). This includes the following goals: that all First Nations women have access to Birthing on Country models of care, advice on stillbirth prevention, and care following stillbirth; and that rates of stillbirth are no greater than those among non-Indigenous Australians.

In July 2020, the National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031, (with infant and child mortality as supporting indicators)

- Target 2: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies with a healthy birthweight to 91 per cent.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Agreement was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around four Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including though working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community-controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision-making by First Nations communities.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations people’s health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement. The Health Plan includes among its priorities a focus on having a strong, sustainable and equipped Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHS) sector to deliver high quality, comprehensive primary health care services that meet the needs of First Nations people including the provision of maternal, antenatal and child health care (Department of Health 2021).

‘Healthy babies and children (Age range: 0–12)’ is one of the key life course phases focused on in the Health Plan, and two objectives specifically address this age range:

- Objective 4.2. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy babies.

- Objective 4.3. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy children.

Both the National Agreement and the Health Plan are discussed further in the Implications section of this measure, along with other actions underway.

Figure 1.21.1: Definitions of perinatal death

Source: Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in Australia (AIHW 2021a).

Data findings

Data in this measure are from the AIHW National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection (NPMDC), with additional information, including demographics, sourced from the National Perinatal Data Collection (see Data sources and quality). These data are sourced from midwives and other birth attendants, who collect information from mothers, perinatal administrative and clinical record systems.

In contrast, deaths data held by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) are sourced from state and territory registrars of Births Deaths and Marriages and are therefore not directly comparable to the NPMDC. The AIHW data collection has been selected because it holds more complete data on the numbers of stillbirths as well as a more complete capture of causes of perinatal deaths using the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) Perinatal Death Classification System. For example, in 2018, based on the NPMDC there were 2,115 stillbirths, compared with 1,682 in the ABS data (AIHW 2020b). In addition, the proportion of deaths where the cause was unspecified or not stated is lower in the NPMDC than in the ABS data (for example, these accounted for 17% of death records in the NPMDC over the 2-year period 2017–2018, compared with 42% in the ABS data) (analysis of ABS 2019, AIHW 2021a). See Data sources and quality for additional information on the differences between these two data collections.

Data are generally combined for the period 2013 (the start of the NPMDC) to 2020, to enable more detailed disaggregation of the data than is possible over a shorter time period.

In the period 2013–2020, nationally, there were 1,682 perinatal deaths of babies of First Nations mothers, corresponding to an average of 210 deaths per year, or 4 deaths each week. Of the 1,682 perinatal deaths:

- 1,140 (68%) were stillbirths (also known as fetal deaths), corresponding to an average of 143 stillbirths each year, or around 3 deaths each week

- 542 (32%) were neonatal deaths (deaths occurring within 28 days of birth), corresponding to an average of 68 neonatal deaths per year, or around 1 death each week (Table D1.21.5, Figure 1.21.2).

Expressed as a population rate, among babies born to First Nations mothers in 2013–2020, there were 15 perinatal deaths per 1,000 births, including 10 stillbirths per 1,000 births. The rate of neonatal deaths among liveborn babies of First Nations mothers in 2013–2020 was 5 per 1,000 livebirths (Table D1.21.5).

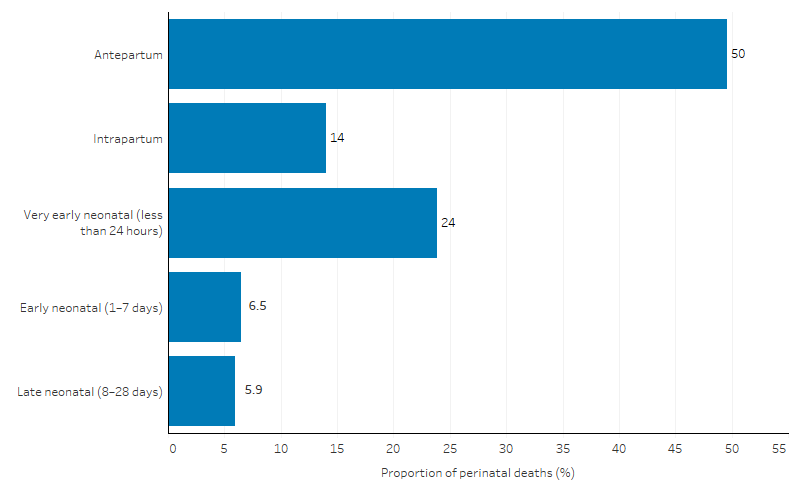

Between 2013–2020, there were 1,483 perinatal deaths of babies of First Nations mothers where the specific timing of perinatal death was recorded. Of these:

- 49.6% (735) occurred as stillbirths prior to birth (antepartum period)

- 14.0% (208) occurred as stillbirths during the labour or birth (intrapartum period)

- 23.9% (355) were very early neonatal deaths (within the first 24 hours following birth)

- 6.5% (97) were early neonatal deaths (1–7 days following birth)

- 5.9% (88) were late neonatal deaths (8–28 days following birth) (percentages calculated after excluding deaths where the timing of the stillbirth or neonatal death was not stated) (Figure 1.21.2) (AIHW 2023).

Figure 1.21.2: Timing of perinatal deaths among babies born to First Nations mothers as a proportion of perinatal deaths, Australia, 2013–2020

Note: These data are not comparable with ABS registrations of deaths data used in previous reporting of this measure (see National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection for details).

Source: AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection (from: AIHW 2023).

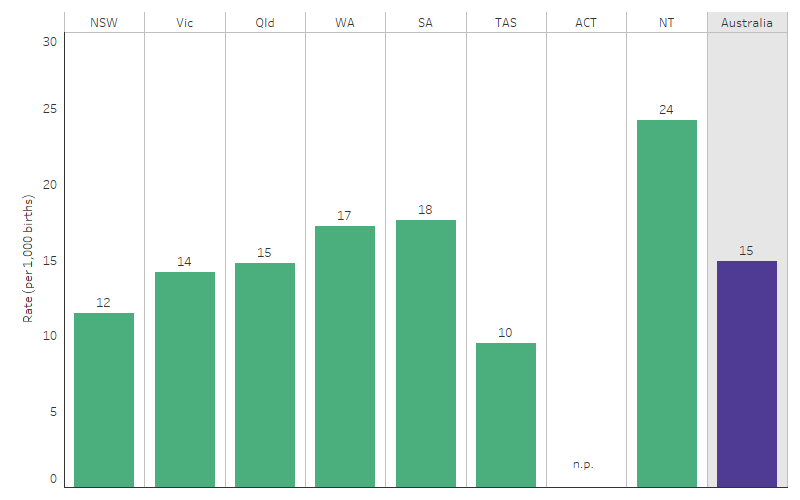

Perinatal death by states and territories

In the 5-year period 2015–2019, where data are available for the states and territories, the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers varied between jurisdictions.

- The rate was highest in the Northern Territory (24.2 deaths per 1,000 births), followed by South Australia (17.6 deaths per 1,000 births) and Western Australia (17.2 deaths per 1,000 births).

- The rate was lowest in Tasmania (9.5 deaths per 1,000 births) and ranged between 12 and 15 deaths per 1,000 births in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland.

- The perinatal death rate in the Northern Territory was 2.5 times as high as that in Tasmania (Table D1.21.4, Figure 1.21.3).

Since the 5-year period 2010–2014, the largest decline in the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers was in Victoria, where the rate declined from 23 to 14 deaths per 1,000 births in 2015–2019. This decline in Victoria was predominantly driven by the decreasing rates of stillbirths (which declined from 17.0 to 10.5 deaths per 1,000 births), with no significant change in the rate of neonatal death among babies born to First Nations mothers (Table D1.21.4).

Figure 1.21.3: Stillbirths, neonatal and perinatal mortality rates for babies born to Indigenous women, Australia, 2010–2014 and 2015–2019

Note: These data are not comparable with ABS registrations of deaths data used in previous reporting of this measure (see National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection for details).

Source: Table D1.21.4. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Perinatal death by remoteness

In the period 2013–2020, rates of perinatal death for babies born to First Nations mothers were higher in more remote areas. The rate was about twice as high in Very remote areas (23 perinatal deaths per 1,000 births) as in Major cities and Inner regional areas (both 13 per 1,000 births) (AIHW 2023) (Figure 1.21.4).

Figure 1.21.4: Perinatal death rates among babies born to First Nations mothers, by remoteness, 2013–2020

Note: These data are not comparable with ABS registrations of deaths data used in previous reporting of this measure (see National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection for details).

Source: AIHW Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies web report (AIHW 2023: table 5.4).

Perinatal death by socioeconomic area

In the period 2013–2020, the perinatal death rate for babies born to First Nations mothers was higher for those living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (17 deaths per 1,000 births) than for babies born to First Nations mothers living in other socioeconomic areas (around 14 deaths per 1,000 births in each of the other 4 quintiles).

When looking separately at stillbirths and neonatal deaths, while rates of both were higher in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, the difference was larger for neonatal deaths. In the period 2013–2020:

- the rate of stillbirths among babies of First Nations mothers who were living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas was 11.1 deaths per 1,000 births, compared with between 9.7 and 10.1 per 1,000 births for those residing in other areas

- the rate of neonatal deaths was 6.1 deaths per 1,000 live births for babies of First Nations mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, compared with between 3.6 and 4.3 per 1,000 live births for mothers living in other areas (AIHW 2023).

Leading cause of perinatal death

In these data, leading causes of perinatal deaths were classified according to the Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ) Perinatal Death Classification System, and percentages were calculated including deaths for which cause of death was not stated. In the period 2013–2020, cause of death was stated for 1,639 (97%) of 1,682 deaths of babies born to First Nations mothers.

In the period 2013–2020, for babies born to First Nations mothers, the top 5 leading causes of perinatal deaths were:

- spontaneous pre-term labour or rupture of membranes (that is, onset of pre-term labour or rupture of membranes at <37 weeks gestation) (352 deaths or 20.9% of perinatal deaths)

- congenital anomalies, including structural, functional, or chromosomal malformations (323 deaths or 19.2% of perinatal deaths)

- unexplained antepartum fetal death (that is, deaths of normally formed fetuses prior to the onset of labour where no predisposing factors are considered likely to have caused the death) (199 deaths or 11.8% of perinatal deaths)

- maternal conditions such as medical (for example, diabetes) or surgical (for example, appendicitis) disorders (180 deaths or 10.7% of perinatal deaths) and

- antepartum haemorrhage (135 deaths or 8.0% of perinatal deaths).

The top 2 leading causes accounted for around 4 in 10 perinatal deaths (675 deaths, 40%) of 1,682 perinatal deaths (Table 1.21-1).

Table 1.21-1: Perinatal deaths among babies born to First Nations mothers, by underlying cause of death (PSANZ-PDC), Australia, 2013–2020

|

PSANZ-Perinatal Death Classification |

Perinatal deaths (number) |

Perinatal deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Spontaneous pre-term labour or rupture of membranes |

352 |

20.9 |

|

Congenital anomaly |

323 |

19.2 |

|

Unexplained antepartum death |

199 |

11.8 |

|

Maternal conditions |

180 |

10.7 |

|

Antepartum haemorrhage |

135 |

8.0 |

|

Other causes of death |

450 |

26.8 |

|

Not stated cause of death |

43 |

2.6 |

|

Total with stated cause of death |

1,682 |

100.0 |

Note: Table shows the leading 5 causes of deaths (with other causes grouped into ‘Other causes of death’). Percentages include deaths where cause was ‘not stated.’ See also Table D1.21.5 for additional data.

Source: Table D1.21.5. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Leading cause of stillbirth

In this section, percentages were calculated including deaths for which cause of death was not stated. In the period 2013–2020, cause of death was stated for 1,116 (97.9%) of 1,140 stillbirth deaths of babies born to First Nations mothers.

In the period 2013–2020, the top 5 leading causes of stillbirth among babies born to First Nations mothers for which cause of deaths was known include:

- congenital anomalies (201 deaths or 17.6% of stillbirths)

- unexplained antepartum deaths (199 deaths or 17.5% of stillbirths)

- maternal conditions (161 deaths or 14.1% of stillbirths)

- spontaneous pre-term labour or rupture of membranes (< 37 weeks’ gestation) (144 or 12.6% of stillbirths) and

- antepartum haemorrhage (104 deaths or 9.1% of stillbirths).

The top 2 leading causes of stillbirths accounted for over one-third (400 deaths, 35%) of 1,140 stillbirths among babies born to First Nations mothers (AIHW 2023) (Table 1.21-2).

Table 1.21-2: Stillbirths among babies born to First Nations mothers, by underlying cause of death (PSANZ-PDC), Australia, 2013–2020

|

PSANZ-Perinatal Death Classification |

Stillbirths (number) |

Stillbirths (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Congenital anomaly |

201 |

17.6 |

|

Unexplained antepartum death |

199 |

17.5 |

|

Maternal conditions |

161 |

14.1 |

|

Spontaneous pre-term labour or rupture of membranes |

144 |

12.6 |

|

Antepartum haemorrhage |

104 |

9.1 |

|

Other causes of death |

307 |

26.9 |

| Not stated cause of death |

24 |

2.1 |

|

Total with stated cause of death |

1,140 |

100.0 |

Note: Table shows the leading 5 causes of deaths (with other causes grouped into ‘Other causes of death’). Percentages include deaths where cause was ‘not stated.’ See also Table D1.21.5 for additional data.

Source: Table D1.21.5. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Leading cause of neonatal death

In this section, percentages were calculated including deaths for which cause of death was not stated. In the period 2013–2020, cause of death was stated for 523 (96.5%) of 542 neonatal deaths of babies born to First Nations mothers.

For babies born to First Nations mothers in the 2013–2020 period, the top 5 leading causes of neonatal death include:

- spontaneous pre-term labour or rupture of membranes (< 37 completed gestational weeks) (208 deaths or 38.4% of neonatal deaths)

- congenital anomaly (122 deaths or 22.5% of neonatal deaths)

- perinatal infection (42 deaths or 7.7% of neonatal deaths)

- specific perinatal conditions (33 or 6.1% of neonatal deaths) and

- antepartum haemorrhage (31 or 5.7% of neonatal deaths).

The top 2 leading causes of death accounted for almost two-thirds (330 deaths, 61%) of 542 neonatal deaths (AIHW 2023) (Table 1.21-3).

Table 1.21-3: Neonatal deaths among babies born to First Nations mothers, by underlying cause of death (PSANZ-PDC), Australia, 2013–2020

|

PSANZ-PDC |

Neonatal deaths (number) |

Neonatal deaths (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Spontaneous pre-term labour or pre-term birth |

208 |

38.4 |

|

Congenital anomaly |

122 |

22.5 |

|

Perinatal infection |

42 |

7.7 |

|

Specific perinatal conditions |

33 |

6.1 |

|

Antepartum haemorrhage |

31 |

5.7 |

|

Other causes of death |

87 |

16.1 |

| Not stated cause of death |

19 |

3.5 |

|

Total (stated) |

542 |

100.0 |

Note: Table shows the leading 5 causes of deaths (with other causes grouped into ‘Other causes of death’). Percentages include deaths where cause was ‘not stated.’ See also Table D1.21.5 for additional data.

Source: Table D1.21.5. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Perinatal death by birthweight

In 2013–2020, among babies born to First Nations mothers, the perinatal death rate for those born with a low birthweight was 36 times as high as with those born with a healthy birthweight (99.5 deaths per 1,000 births compared with 2.8 deaths per 1,000 births).

In 2013–2020, for babies born to First Nations mothers:

- 84% (1,374 deaths) of the total perinatal deaths occurred among babies born with a low birthweight

- 84% (930 deaths) of the total stillbirths occurred among babies born with a low birthweight

- 83% (444 deaths) of the total neonatal deaths occurred among babies born with a low birthweight (AIHW 2023).

Perinatal death by gestational age

In 2013–2020, the perinatal death rate among babies born to First Nations mothers decreased with increasing gestational age, from 997 deaths per 1,000 births for those with a gestational age of 20–22 weeks to 3.3 deaths per 1,000 births for those born at 36 weeks and over.

In the same period, of perinatal deaths where gestational age was known and among babies born to First Nations mothers:

- 61% were among babies born between 20 and 26 weeks (that is, 1,020 deaths)

- 20% were among babies born between 27 and 35 weeks (331 deaths) and

- 19% were among those born at 36 weeks or more (324 deaths) (percentages calculated after excluding deaths were gestational age was not stated) (AIHW 2023).

Comparing gestational age of stillbirths with neonatal deaths for babies born to First Nations mothers (where gestational age was known) in 2013–2020:

- 59% (665 deaths) of stillbirths occurred among babies born between 20 and 26 weeks – lower than the proportion for neonatal deaths (66% or 355 deaths)

- 22% (253 deaths) of stillbirths occurred between 27 and 35 weeks – higher than the proportion of neonatal deaths (14% or 78 deaths)

- 19% (217 deaths) of stillbirths occurred at 36 weeks or more, similar to the proportion of neonatal deaths (20% or 107 deaths) (AIHW 2023).

Key comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

In 2013–2020, deaths of babies of First Nations mothers represented:

- 7.3% of total perinatal deaths (1,682 of 23,087)

- 6.6% of total stillbirths (1,140 of 17,143)

- 9.1% of total neonatal deaths (542 of 5,944).

The perinatal death rate among babies born to First Nations mothers was 1.7 times as high as for babies born to non-Indigenous mothers – 15.4 deaths compared with 9.2 deaths per 1,000 births. The rate of stillbirth of babies born to First Nations mothers was 1.5 times as high as for babies born to non-Indigenous mothers (10.4 compared with 6.8 per 1000 births), and the rate of neonatal deaths was 2.0 times as high (5.0 compared with 2.4 per 1,000 live births) (Table D1.21.1).

In the period 2015–2019, data by state and territory indicate that the perinatal mortality rate was higher for babies born to First Nations mothers than for babies born to non-Indigenous mothers in most jurisdictions, except Tasmania where the rates were similar (Table D1.21.4, excludes Australian Capital Territory due to small numbers).

Changes over time

Due to the small number of deaths, time series data for perinatal death rates are volatile and should be interpreted with caution. Large percentage fluctuations from year to year could be due to small variations in death numbers.

To describe trends in perinatal death data, linear regression has been used to calculate the per cent change over time. This means that information from all years of the specified time period are used, rather than only the first and last points in the series (see Statistical terms and methods).

Over the decade from 2011 to 2020, there was no statistically significant change in the perinatal death rate among babies born to First Nations or non-Indigenous mothers. Moreover, there was no statistically significant change in the absolute gap (rate difference) in the perinatal death rate between First Nations mothers and non-Indigenous mothers over this period. Consistent with the trend for total perinatal deaths, between 2011 and 2020, there were also no statistically significant changes in the separate rates of stillbirths or neonatal deaths for babies born to First Nations or non-Indigenous mothers, nor in the gap in rates of stillbirths and neonatal deaths between First Nations mothers and non-Indigenous mothers (Table D1.21.3).

The relative difference (rate ratio) in perinatal death rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers has fluctuated over the last decade. Between 2011 and 2020, the relative difference between the two populations (rate ratio) for both total perinatal death and stillbirth rates was highest in 2011 (2.0 and 1.9, respectively) and was lowest in 2015 (1.3 and 1.2, respectively). For neonatal death rates, the relative difference between the First Nations and non-Indigenous populations ranged between 1.7 (in 2015) and 2.6 (in 2013) (Table D1.21.2, Table D1.21.3, Figure 1.21.5).

Figure 1.21.5: Perinatal, stillbirth and neonatal death rates and changes in the gap, by Indigenous status of the mother, Australia, 2011 to 2020

Note: These data are not comparable with ABS registrations of deaths data used in previous reporting of this measure (see National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection for details).

Sources: Table D1.21.2 and D1.21.3. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Mortality Data Collection and the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Research and evaluation findings

Analysis by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare identified strategies for improving First Nations child mortality (based on the literature), such as enhancing access to antenatal care, immunisation and health checks. The analysis also explored the timeframe for observing health improvements following implementation of programs that may impact child and maternal health. Some measures are more likely to show immediate effects (such as antenatal care or immunisation), while some measures targeting social determinants or public health require more time to significantly influence risk factors (such as smoking, nutrition, alcohol use) on the way to improving maternal health and ultimately child health outcomes (AIHW 2014).

Panaretto et al. (2007) showed that sustained access to community-based, integrated, and shared antenatal services for First Nations mothers improved perinatal outcomes. The study of women attending the Mums and Babies program at the Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Service demonstrated significant improvements in care planning, completion of cycle-of-care, and antenatal education activities with a significant reduction in perinatal mortality. Comparing the study groups, the rate of perinatal mortality in the pre-study group was 4.3 times as high as the rate in the study group (60 and 14 per 1,000 births, respectively; p<0.014) and the average number of antenatal visits was half that of the study group (3 compared with 6; p<0.001) (Panaretto et al. 2007).

A trial was undertaken to study the effects of ‘Birthing on Country’ service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations people in Queensland. Research from the trial focused on the clinical effectiveness of the "Birthing in Our Community” (BiOC) service, a partnership between the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane, and the Mater Mothers’ Hospital. A total of 1,422 women were included in the analysis who received either standard care (656 participants) or the BiOC service (766 participants) between 1 January 2013, and 30 June 2019. The results showed that women engaged with the BiOC service were more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal care visits, had a reduced likelihood of pre-term birth, and were more likely to exclusively breastfeed upon hospital discharge. However, there was no significant difference in smoking rates after 20 weeks of gestation. For the women engaged with the BiOC service there were also differences in labour care outcomes (such as fewer epidurals in the first stage of labour, fewer planned caesarean sections, being less likely to be admitted to a special neonatal care nursery or neonatal intensive care unit, and being more likely to have their third stage of labour managed without intervention) compared with those receiving standard care. The study concluded that the BiOC service, grounded in Birthing on Country principles, has demonstrated clinical effectiveness and resulted in significantly improved maternal and infant outcomes (Kildea et al. 2021).

A cost-effectiveness study of the same BiOC service showed that it offers a cost-effective alternative to standard care for reducing the proportion of pre-term births and providing cost savings per mother-baby pair. The cost savings were driven by less interventions and procedures in birth and fewer neonatal admissions (Gao et al. 2023).

Smoking during pregnancy has been shown as one of the main contributing factors to a range of poor perinatal outcomes including low birthweight, pre-term birth and perinatal deaths (AIHW 2020a). Therefore, addressing the high rates of smoking during pregnancy has been a key focus of efforts to improve First Nations maternal and child health (for more information see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy).

An international systematic review and meta-analysis found that smoking during pregnancy was significantly associated with a 47% increase in the odds of stillbirth. Smoking 1–9 cigarettes per day was associated with a 9% increase in the odds of stillbirth whereas smoking 10 or more cigarettes per day was associated with a 52% increase in the odds of stillbirth. The review found a dose-response effect of maternal smoking during pregnancy on risk of stillbirth, highlighting the importance of reducing smoking prevalence in pregnancy as a key public health priority (Marufu et al. 2015).

First Nations women in Australia are motivated to stop smoking during pregnancy and are making attempts to quit (Colonna et al. 2020). A review of evidence on smoking among First Nations people found that knowledge about the direct and indirect health effects of smoking can be influential in changing behaviour, including among pregnant women. First Nations women who quit smoking during pregnancy were found to have a better understanding of the health risks to their baby than those who continued smoking (Colonna et al. 2020). Another review by Harris et al. (2019) found that social and familial influences and stress levels have a strong impact on quitting smoking during pregnancy. However, information and advice regarding potential adverse effects of smoking on the baby, or lack thereof, from health professionals either facilitated smoking cessation or was a barrier to quitting. A lack of awareness of smoking cessation strategies among midwives and doctors was identified as a barrier to smoking cessation among First Nations pregnant women. Involving pregnant First Nations women’s partners, support people and family in education on the adverse effects of smoking and the benefits of smoking cessation strategies, may have a positive effect on attempts to stop smoking, as this can lead to the women being supported in their decision to quit. Additional professional development for health professionals to facilitate smoking cessation in a culturally competent manner is also needed (Harris et al. 2019).

A national cross-sectional survey of First Nations women in Australia aged 16–49 who were smokers or ex-smokers found that 36% have used nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and/or stop-smoking medications (SSM). Older women (35–49 years) were more likely to have sustained a quit attempt for years and to have tried NRT and/or SSM than younger women. Quitting smoking suddenly, rather than gradually reducing cigarette consumption, was significantly associated with sustained abstinence. Despite the willingness to quit, most women who had never used NRT or SSM cited reasons such as ‘wanting to quit on my own without help’, cost, and a preference not to use medications as the main reasons for not using NRT or SSM. The study emphasised the role of health providers in offering consistent cessation support and in providing a range of cessation options to clients (Kennedy et al. 2022).

An international systematic review and meta-analysis found that indigenous women are at increased risk of mental health problems during the perinatal period, particularly depression, anxiety and substance use. The review covered evidence from Canada, the United States, New Zealand, Taiwan, and included 6 studies of First Nations women. However, the available evidence had significant methodological limitations, and other conflicting evidence had also been published which did not show increased risks between indigenous and non-indigenous women, while also highlighting the strong resilience of indigenous peoples (Owais et al. 2020). Furthermore, while the association of maternal mental health conditions and adverse perinatal outcomes for babies has been studied in the general population there is limited evidence specifically for First Nations women and their babies. A large retrospective cohort study, using data linkage, including all Western Australian First Nations singleton births (1990–2015, N=38,592), investigated First Nations maternal mental health and associations with perinatal outcomes. The study found that after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and pre-existing medical conditions, having a maternal mental disorder (within the five years prior to giving birth) was associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including pre-term birth, small for gestational age (SGA), perinatal mortality, major congenital abnormalities, foetal distress, low birthweight, and a low Apgar score. The authors argued that there is a need for prevention and early identification of First Nations women with mental health conditions and their service needs, using culturally validated tools, and a need for holistic and culturally safe antenatal care, treatment, and support to help improve perinatal outcomes among First Nations births (Adane et al. 2023).

Gibberd et al. (2019) found that a large proportion of adverse birth outcomes (SGA births, pre-term births, and perinatal deaths) among First Nations infants were attributable to the risk factors of tobacco use, alcohol consumption, drug use and assault of the mother (based on hospitalisation for assault over the period from giving birth back to two years prior to the start of pregnancy). Among 28,119 First Nations singleton infants born in Western Australia between 1998 and 2010:

- 16% of infants were SGA, 13% were pre-term, and 2% died in the perinatal period

- 51% of infants were exposed to at least one of the risk factors of smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use or assault of the mother

- 37% of SGA births, 16% of pre-term births and 20% perinatal deaths could be attributed to smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use or assault against the mother (combined)

- Maternal smoking was associated with 49% higher odds of perinatal death

- Alcohol use was associated with 83% higher odds of perinatal death (Gibberd et al. 2019).

A retrospective population-based cohort study of all births documented in the Top End of the Northern Territory over the period from 2008 to 2017 analysed pre-term birth rates among First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers. The study also described the overall prevalence of maternal characteristics, obstetric complications and labour/birth characteristics. During the decade ending in 2017, annual rates of pre-term birth in the Top End of the Northern Territory remained consistently close to 10% of total live births. However, First Nations women experienced more than twice the risk of pre-term birth (16%) compared to non-Indigenous women (7%). The leading risk factors for pre-term birth included premature rupture of membranes, multiple pregnancy, antepartum haemorrhage, and pre-existing diabetes. The study concluded that smoking during pregnancy, socioeconomic factors, pre-existing chronic diseases, and pregnancy complications are avenues for policy and clinical intervention, but further exploration is warranted (Brown et al. 2024).

Another study of First Nations mothers in the Northern Territory found that adolescents were more likely than 20–34 year olds to have vaginal births with a gestation period of 37–41 weeks and a vertex presentation. While babies of adolescents weighed 135 grams less than those of adults, once adjusting for remoteness, antenatal visits and other factors, differences were eliminated. The study concluded that young maternal age is not a risk factor for adverse perinatal outcomes among First Nations women, but rather, having babies in disadvantaged circumstances meant they were challenged socially and clinically (Steenkamp et al. 2017).

The Australian Burden of Disease Study found that in 2018, intimate partner violence ranked as the fourth leading risk factor (3.7%) for total disease burden among Australian women aged 25 to 44 years (AIHW 2021b). Family violence often commences or intensifies during pregnancy and is associated with poor perinatal and maternal outcomes, with increased rates of: miscarriage; low birthweight; premature birth; foetal injury and perinatal death; maternal substance use and smoking; maternal depression; post-natal depression; and maternal death (Campo 2015; Victorian Government 2021). In 2021–22, among substantiated cases of maltreatment of First Nations children, 17% were for children aged under 1, including unborn children (see measure 2.12 Child protection). However, as Doherty et al. (2022) argue, an increase in prebirth child protection notifications is creating barriers for pregnant First Nations women who are experiencing or fleeing family violence to access appropriate and regular antenatal and neonatal care, for fear of alerting the child protection authorities. Pregnant First Nations women experiencing family violence and/or homelessness often find that housing services are incapable or ill-equipped to support them, leaving these women to fall through the cracks in the system (Doherty et al. 2022).

Implications

In Australia, the First Nations perinatal mortality rate remains high and there has been no progress between 2011 and 2020.

While much of the data findings and research describes the measured clinical and modifiable risk factors impacting upon maternal and child health, there also needs to be understanding among health professionals and policy makers of the social and cultural factors (both risk and protective factors) that impact maternal and child health outcomes for First Nations people. Not all of these broader factors are measured in existing data sets. This broader understanding is increasingly being reflected in key policy documents that emphasise the need for continued and enhanced efforts to improve maternal and child health, and the need to improve access to culturally safe maternity care. However, there needs to be more up-to-date analysis of service delivery gaps which affect access to culturally safe maternity care, and analysis of the potential benefits to First Nations maternal and child health outcomes should those service gaps be filled.

The ACCHS sector has an important role in leading culturally safe and responsive health care within First Nations communities (Panaretto et al. 2014). ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations.

A key component of improving pregnancy outcomes is early and ongoing engagement in antenatal care, which is facilitated by the provision of culturally safe and evidence-based care relevant to the local community (AHMAC 2012; Clarke & Boyle 2014). These services also need to be geographically accessible and offer outreach services and home visits, and also provide continuity of care and integration with other services (AHMAC 2012). Strategies addressing modifiable risk factors (such as smoking, alcohol and substance use) as well as fostering positive health behaviours (such as healthy diet and exercise) should be an important focus of antenatal care delivery (see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy and measure 3.01 Antenatal care) but, as mentioned above, implementation needs to be done with understanding of the broader social and cultural context in which First Nations mothers live.

This highlights the centrality of culture and the importance of strengthening communities, reinforcing positive behaviours and improving the social and cultural determinants of health (Department of Health 2015). This has been emphasised again in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course. The Health Plan, released in December 2021, is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap health targets and priority reforms. Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Health Plan states that a child’s experiences in utero, birth, infancy and childhood can profoundly impact their health throughout life. Positive, accessible, and culturally safe reproductive, antenatal and infant health services are critical to supporting improvements in birth outcomes and mortality, and reducing preventable illness. Birthing on Country services have the potential to support healthy pregnancies and should be explored as a way to offer an integrated, holistic and culturally safe model of care. For example, Birthing on Country services can support reduction and cessation of smoking in pregnancy through health-literacy approaches (Department of Health 2021).

Research has shown that Birthing on Country (BoC) models of care, which offer culturally safe, continuous midwifery care for First Nations women, can improve birth outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies (such as improving frequency of antenatal care visits and reducing the likelihood of pre-term birth).

The Australian Government is actively promoting the Birthing on Country (BoC) model, especially in rural and remote areas where birthing outcomes can be challenging. To support this, the Australian Government has committed to investing $45 million over four years from 2021–22 to 2024–25 under the Healthy Mums Healthy Bubs initiative to enhance the maternity health workforce and support BoC practices. This includes $12.8 million to expand the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program from 13 to 15 sites. Additional funding ($22.5 million) has also been allocated from 2022–23 to 2024–25 for the establishment of a BoC Centre of Excellence at Waminda in Nowra, New South Wales. The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) also funded The Birthing on Country: RISE SAFELY study with $5 million, which will establish exemplar BoC services in three rural, remote and very remote settings. The study is First Nations led, co-designed and staffed. The Department of Health and Aged Care is also partnering with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to develop a maternal and child health model of care to enable First Nations mothers and families to access consistent, culturally safe and effective care, as part of Closing the Gap implementation planning (NIAA 2023).

Australian governments are investing in a range of other initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. These include the National Tobacco Campaign’s Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program, the iSISTAQUIT program, Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy: 2019 and Beyond, and the National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan. See also measures 1.01 Birthweight; 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy; and 3.01 Antenatal care.

The Health Plan represents the Australian Government’s ongoing commitment to lead the systemic change needed to improve health outcomes for First Nations people. As demonstrated through the National Agreement on Closing the Gap, this means fundamentally changing the way governments work with First Nations stakeholders, organisations, communities and individuals.

As part of the National Agreement, the community-controlled health sector was identified as one of 4 initial sectors for joint national strengthening effort and the development of a 3-year Sector Strengthening Plan. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) was developed in 2021, to acknowledge and respond to the scope of key challenges for the sector, providing 17 transformative sector strengthening actions. Developed through strong consultation across the First Nations community-controlled health sector and other First Nations health organisations, the Health-SSP will be used to prioritise, partner and negotiate beneficial sector-strengthening strategies.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Cat. no. 2033.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

-

ABS 2019. Causes of Death, Australia, 2018. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- ABS & AIHW (Australian Bureau of Statistics & Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2008. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2008. Canberra: ABS & AIHW.

- Adane A, Shepherd C, Walker R, Bailey H, Galbally M & Marriott R 2023. Perinatal outcomes of Aboriginal women with mental health disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57.

- AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2012. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. (ed., Department of Health and Ageing). Canberra: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Headline indicators for children's health, development and wellbeing 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2020a. Antenatal care use and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and their babies 2016–2017. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2020b. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in Australia. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2021a. Stillbirths and neonatal deaths in Australia 2017–2018. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2021b. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2018 – Key findings. Cat. no. BOD 28. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 19 October.

- AIHW 2023. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies. Canberra.

- Brown K, Cotaru C & Binks M 2024. A retrospective, longitudinal cohort study of trends and risk factors for preterm birth in the Northern Territory, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 24.

- Brown S, Mensah FK, Ah Kit J, Stuart-Butler D, Glover K, Leane C et al. 2016. Aboriginal Families Study Policy Brief No 4: Improving the health of Aboriginal babies. Melbourne: MCRI.

- Campo M 2015. Domestic and family violence in pregnancy and early parenthood: Overview and emerging interventions (ed., Studies AIoF). Melbourne, Victoria: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

- Clarke M & Boyle J 2014. Antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australian Family Physician 43:20-4.

- Colonna E, Maddox R, Cohen R, Marmor A, Doery K, Thurber K et al. 2020. Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- Department of Health 2015. Implementation plan for the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2013–2023. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

- Department of Health 2020. National Stillbirth Action and Implementation Plan. Canberra: Department of Health.

- Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2021–2031. Government of Australia.

- Doherty J, McNicol E & Morgan E 2022. Culture and care for pregnant unhoused Aboriginal women. Parity 35.

- Eades S 2004. Maternal and Child Health Care Services: Actions in the Primary Health Care Setting to Improve the Health of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women of Childbearing age, Infants and Young Children. Darwin: OATSIH.

- Eades S, Read AW, Stanley FJ, Eades FN, McCaullay D & Williamson A 2008. Bibbulung Gnarneep ('solid kid'): causal pathways to poor birth outcomes in an urban Aboriginal birth cohort. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 44:342-6.

- Gao Y, Roe Y, Hickey S, Chadha A, Kruske S, Nelson C et al. 2023. Birthing on country service compared to standard care for First Nations Australians: a cost-effectiveness analysis from a health system perspective. The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific.

- Gibberd A, Simpson JM, Jones J, Williams R, Stanley F & Eades SJ 2019. A large proportion of poor birth outcomes among Aboriginal Western Australians are attributable to smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, and assault. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 19.

-

Harris B, Harris M, Rae K & Chojenta C 2019. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation within pregnant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women: An integrative review. Midwifery 73:49-61.

-

Kennedy M, Barrett E, Heris C, Mersha A, Chamberlain C, Hussein P et al. 2022. Smoking and quitting characteristics of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women of reproductive age: findings from the Which Way? study. Medical Journal of Australia 217:S6-S18.

-

Khalidi N, McGill K, Houweling H, Arnett K & Sheahan A 2012. Closing the Gap in Low Birthweight Births between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Mothers, Queensland. (ed., Health Statistics Centre, Queensland Health). Brisbane: QLD Health.

-

Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, Nelson C, Kruske S, Carson A et al. 2021. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial. Lancet Glob Health 9:e651-e9.

-

Marufu T, Ahankari A, Coleman T & Lewis S 2015. Maternal smoking and the risk of still birth: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 15.

-

NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency) 2023. Commonwealth Closing the Gap Implementation Plan 2023. (ed., National Indigenous Australians Agency). Canberra.

-

Owais S, Faltyn M, Johnson AG, C, Downey B, Kates N & Van Lieshout R 2020. The Perinatal Mental Health of Indigenous Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Can J Psychiatry 65.

-

Panaretto K, Mitchell M, Anderson L, Larkins S, Manessis V, Buettner P et al. 2007. Sustainable antenatal care services in an urban Indigenous community: the Townsville experience. Medical Journal of Australia 187:18-22.

-

Panaretto K, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring I 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

Performance Indicator Reporting Committee 2002. Plan for Federal/Provincial/Territorial Reporting on 14 Indicator Areas. Canada: PIRC. -

Sayers S & Powers J 1997. Risk factors for aboriginal low birthweight, intrauterine growth retardation and preterm birth in the Darwin Health Region. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 21:524-30.

-

Steenkamp M, Boyle J, Kildea S, Moore V, Davies M & Rumbold A 2017. Perinatal outcomes among young Indigenous Australian mothers: A cross-sectional study and comparison with adult Indigenous mothers. Birth 44:262-71.

-

Victorian Government 2021. Evidence-based risk factors and the MARAM risk assessment tools. Victoria: Victorian Government.