Key messages

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) cultures take a holistic view of wellbeing and have many strengths that provide a positive influence on wellbeing and resilience for First Nations mothers and their families.

- For women who experience adverse events in their pregnancies, the factors that influence these outcomes can be diverse, reflecting a range of social and cultural determinants of health as well as health behaviours, biomedical risks and poor access to appropriate services.

- In 2020, the rate of alcohol consumption among First Nations mothers in the second 20 weeks of pregnancy was 3.6% – down from 8.2% in the first 20 weeks.

- In 2020, 43% of First Nations mothers smoked tobacco during pregnancy – a decrease from 50% in 2011 (based on crude rates). Nationally, the smoking rate was lower for the period after 20 weeks of pregnancy than the first 20 weeks (38% compared with 42%).

- An estimated 38% of low birthweight singleton births of First Nations singleton babies in 2018–2020 were attributable to smoking during pregnancy, based on a multivariate analysis.

- In 2020, the pre-term birth rate among babies born to First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy was 1.6 times the rate among those born to First Nations mothers who did not smoke (16.3% and 9.9%, respectively).

- Using age-standardised rates, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy declined by 9.2% between 2011 and 2020, while for non-Indigenous mothers the proportion declined by 24.1%. As a result, the relative difference in smoking rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers increased over this period – from 3.2 times as high for First Nations mothers in 2011, to 3.8 times as high in 2020.

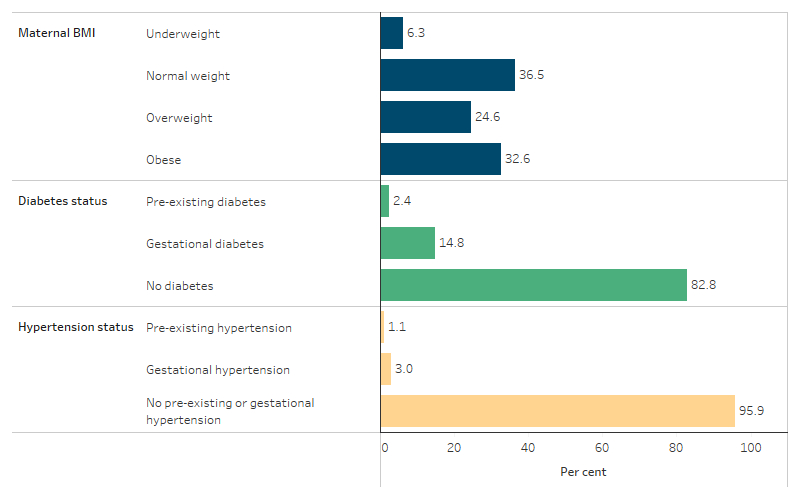

- Among First Nations mothers who gave birth in 2020, 57.2% were overweight or obese prior to their pregnancy, 14.8% had gestational diabetes, 2.4% had pre-existing diabetes, 3.0% had gestational hypertension and 1.1% had pre-existing hypertension.

- In the Fitzroy Valley, First Nations women identified the need to address Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) in 2008. Between 2010 and 2016, a range of community-led FASD prevention activities were implemented, including television and radio mass media advertisements; targeted health promotion messaging coordinated and delivered through local First Nations organisations; and screening of all pregnant women by community midwives for alcohol use, with referral and encouragement to access services if needed. An evaluation found that Fitzroy Valley women reporting the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy reduced significantly from 61.0% in 2010 to 31.9% in 2015 over a period during which community-led prevention efforts took place.

- A study of the spatial variation in First Nations women’s access to maternal health services found that poorer access to at least one type of maternal health service was associated with higher rates of smoking, pre-term delivery and low birthweight. Poorer access to First Nations-specific primary health care services was associated with higher levels of smoking and low birthweight. One-fifth of First Nations women aged 15–44 lived more than one hour from the nearest hospital with a public birthing unit (20.5%), and 15% of First Nations women lived more than one hour from a First Nations-specific primary health care service offering antenatal or maternal services.

- Spatial variation in access to programs to reduce smoking before, during and after pregnancy is currently a data gap.

- Findings of this measure need to be interpreted in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had negative impacts on First Nations people’s health and wellbeing as reflected in the data presented in this measure.

Why is it important?

The origins of health behaviours are located in a complex range of socioeconomic, family and community factors, arising from environments shaped by political, social and economic forces (Nettleton et al. 2007). These social determinants of health are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, and are mostly responsible for health inequalities (WHO 2022). The health and wellbeing of women during pregnancy is vitally important to ensuring healthy outcomes for mothers and their babies (AIHW 2020). Many factors contribute to and can have beneficial or adverse effects on the health and wellbeing of a mother and her baby during pregnancy and birth, as well as outcomes for children and adults later in life. Women who eat well, exercise regularly and receive regular antenatal care are less likely to have complications during pregnancy. They are also more likely to give birth to a healthy baby. Healthy nutrition before and during pregnancy is essential for fetal development (McDermott et al. 2009; Wen et al. 2010). Maintenance of folate levels is particularly important to decrease the risk of neural tube defects such as spina bifida (AHMAC 2012). Smoking, drinking, or taking illicit drugs can lead to increased risk of pregnancy complications, poor perinatal outcomes (such as low birthweight and developmental anomalies), and ongoing health concerns.

Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) women have healthy pregnancies (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Health is a holistic concept for First Nations people; with social and emotional wellbeing as well as cultural, ecological and spiritual aspects viewed as the foundation of physical and mental health (Bourke et al. 2018; Verbunt et al. 2021). As such, the health and wellbeing of an individual is linked to the wellbeing of their family, community, environment, and culture (Bourke et al. 2018). First Nations cultures have many strengths that provide a positive influence on wellbeing and resilience for First Nations women and their families. These include a supportive extended family network and kinship, connection to Country and cultural practices such as languages, art, and music. For women who experience adverse events in their pregnancies, the factors that influence these outcomes can be diverse, reflecting a range of social determinants of health as well as health behaviours and biomedical risks. These include:

- socioeconomic factors: lower income, higher unemployment, lower educational levels, inadequate infrastructure (for example, affordable housing and water supply), lack of access to culturally safe health services (including maternal health services – particularly for those living in rural and remote areas), affordable healthy food and transportation options

- health factors: diabetes, cardiovascular disease (including rheumatic heart disease), respiratory disease, kidney disease, anaemia, communicable infections, injuries, poor mental health, and being overweight or underweight

- protective/risk factors: physical activity, food security and nutrition, harmful alcohol and other drug use, smoking and higher psychosocial stressors (for example, deaths in families, violence, serious illness, financial pressures and contact with the justice system).

In addition, racism and other upstream determinants including the pervasive effects of colonisation constitute to a ‘double burden’ for First Nations people, affecting their health and access to adequate and timely health care services (Kildea et al. 2016).

Supporting attendance at antenatal care (see measure 3.01 Antenatal care) and addressing maternal nutritional status, illness during pregnancy, pre-existing high blood pressure and diabetes, and socioeconomic disadvantage can lead to improved outcomes for First Nations women and babies (ABS & AIHW 2008; AIHW 2011; Brown et al. 2016a; Eades et al. 2008; Khalidi et al. 2012; Panaretto et al. 2014; Sayers & Powers 1997).

The literature suggests that one way to improve outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies is through improved access to, and take-up of, antenatal care services (AIHW 2014). Australian government-funded antenatal care programs led by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) for First Nations women have been shown to have an impact on maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal nutrition, and breastfeeding practices, and that this, in turn, can reduce the rates of low birthweight, pre-term birth, and child mortality (AIHW 2014). The ACCHSs sector plays a significant role in providing comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people, including antenatal programs which have delivered improved outcomes for maternal and child health (Panaretto et al. 2007; Panaretto et al. 2014).

Health behaviours during pregnancy among First Nations women need to be understood in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations peoples and cultures. This history and the ongoing impacts of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and poorer outcomes for First Nations peoples (Productivity Commission 2023).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including through working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community-controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision making by First Nations communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031, (with infant and child mortality as supporting indicators)

- Target 2: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies with a healthy birthweight to 91 per cent (with smoking during pregnancy and alcohol use during pregnancy as supporting indicators).

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement.

‘Healthy babies and children (Age range: 0–12)’ is one of the key life course phases focused on in the Health Plan, and 2 objectives specifically address this age range:

- Objective 4.2. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy babies.

- Objective 4.3. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy children.

The Health Plan is discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

Smoking during pregnancy among First Nations mothers

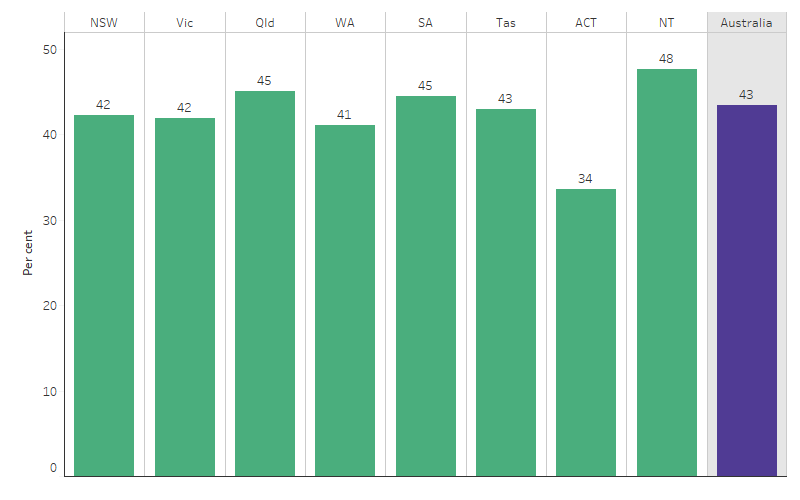

Around 43% of First Nations mothers who gave birth smoked tobacco during pregnancy in 2020, according to self-reported data from the National Perinatal Data Collection (Figure 2.21.1).

In 2020, across maternal age groups, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during their pregnancy was slightly higher among those in the younger age groups (46% among those aged under 20; 45% for those aged 20¬–24) compared with those in the older age groups (ranged from 41% to 44% among those aged 25 and over) (Table D2.21.2).

Across states and territories, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy in 2020 ranged from 34% in the Australian Capital Territory to 48% in the Northern Territory (Table D2.21.1, Figure 2.21.1).

Figure 2.21.1: Proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy, by state and territory, 2020

Source: Table D2.21.1. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

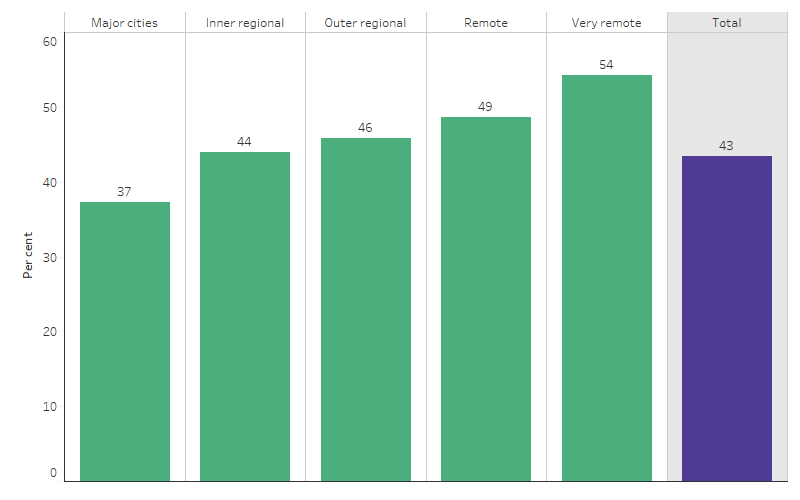

The rate of smoking during pregnancy among First Nations mothers was higher in more remote areas. In Major cities, 37% of First Nations mothers who gave birth in 2020 smoked during pregnancy, compared with 54% in Very remote areas (Table D2.21.2, Figure 2.21.2).

Figure 2.21.2: Proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy, by remoteness, 2020

Source: Table D2.21.2. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

To improve the experience and quality of health services provided for First Nations people, First Nations-specific primary health care services were established to provide holistic and comprehensive primary care services specially designed for First Nations people.

As at June 2023, of the 4,911 regular female clients of First Nations-specific primary health care organisations who gave birth during the previous 12 months, 42% (or 2,059 female clients) were current smokers. The proportion of current smokers generally increased with increasing remoteness: 32% in Major cities, 37% in Inner regional, 49% in Outer regional, 48% in Remote and 49% in Very remote areas (Table D2.21.13).

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy was higher than the proportion who smoked after 20 weeks of pregnancy (42% and 38%, respectively), a difference of 4 percentage points. The difference in smoking rates for First Nations mothers between the first 20 weeks of pregnancy to after 20 weeks was higher in remote areas (5.1 percentage points) compared with non-remote areas (4.3 percentage points) (Table D2.21.16, Table D2.21.18).

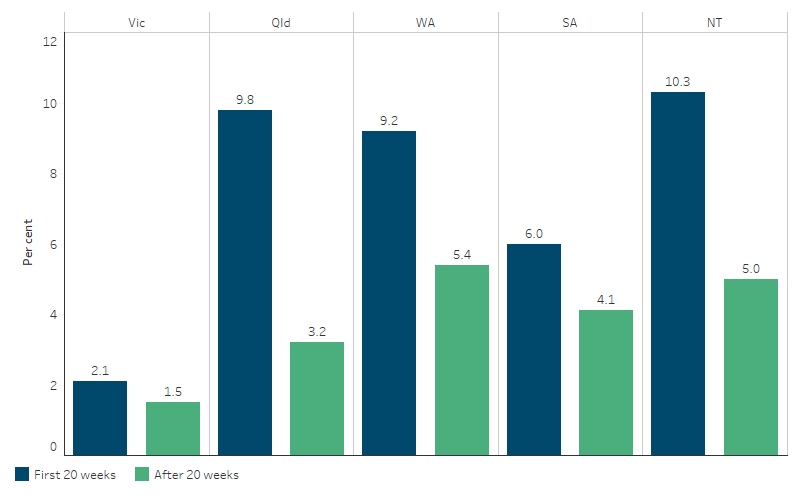

Across states and territories, the difference in smoking rates for First Nations mothers between the first 20 weeks of pregnancy and after 20 weeks was largest in Victoria (8.2 percentage points), followed by the Northern Territory and Queensland (6.3 and 6.2 percentage points, respectively) (Table D2.21.9, Table D2.21.10, Figure 2.21.3).

Figure 2.21.3: Proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, and after 20 weeks, by state and territory, 2020

Source: Table D2.21.9, Table D2.21.10. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy was highest for those aged under 20 (44%) while the proportion of those who smoked after 20 weeks of pregnancy was highest for those aged 20–24 and 35–39 (both 39%). Across all age groups the proportion of mothers who smoked after 20 weeks of pregnancy was lower than in the first 20 weeks. The largest difference was for those aged under 20 (6.1 percentage points), while the smallest occurred among those aged 30–34 and 35–39 (both 3.7 percentage points) (Table D2.21.17, Table D2.21.19).

Smoking and low birthweight

Babies are born with a low birthweight because they are born early (pre-term) or because their growth during pregnancy is restricted, resulting in the baby being small for their gestational age (SGA), or both. Maternal smoking increases the chances that a baby will be born with a low birthweight. The main contributing factors to pre-term births and SGA births differ somewhat, but maternal smoking increases the chances that a baby will be born pre-term or SGA (AIHW 2022b).

In 2020, babies born to First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy were:

- 1.6 times as likely to be pre-term as those born to First Nations mothers who did not smoke (16.3% and 9.9%, respectively)

- 1.6 times as likely to weigh less than 1,500 grams (very low birthweight) as those born to First Nations mothers who did not smoke (2.1% and 1.3%, respectively)

- 2.6 times as likely to weigh 1,500-2,499 grams (low birthweight, excluding very low birth weight) as those born to First Nations mothers who did not smoke (14.3% and 5.5%, respectively) (Table D2.21.4).

The 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey data shows an association between mothers having regular visits to antenatal care services and children’s birthweight. Of First Nations mothers of children with a birthweight of 2,500 grams or more, 98% had regular visits to antenatal care services compared with 84% among mothers of children with low birthweight (<2,500 grams) (Table D2.21.8).

Smoking rates – comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

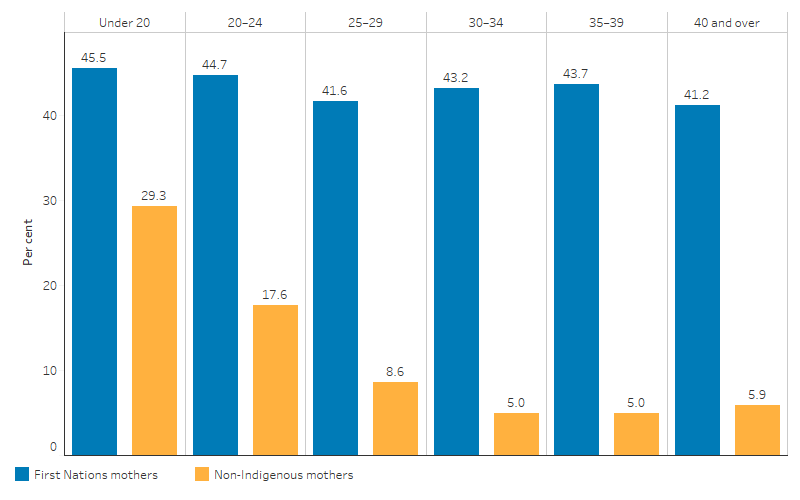

First Nations mothers were more likely than non-Indigenous mothers to smoke tobacco during pregnancy across all age groups (Figure 2.21.4). However, the pattern across age groups is different when comparing the 2 populations. Among non-Indigenous women who gave birth in 2020, rates of smoking during pregnancy were higher in younger age groups – 29.3% among those aged under 20, 17.6% among those aged 20–24, and between 5.0% and 8.6% among those in the older age groups.

The proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy was 4.2 percentage points lower after 20 weeks of pregnancy than in the first 20 weeks (38.0% and 42.2%, respectively). For non-Indigenous mothers, the rate after 20 weeks was 2.9 percentage points lower than in the first 20 weeks (8.0% and 10.9%, respectively). As a result, the gap (absolute difference) in smoking rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers was slightly smaller in the second 20 weeks than in the first (31.3 compared with 29.6 percentage points) (Table D2.21.17, Table D2.21.19).

Figure 2.21.4: Proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy, by age group and Indigenous status, 2020

Source: Table D2.21.2. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the 2 populations, in 2020:

- First Nations mothers were 3.8 times as likely to smoke at any time during pregnancy as non-Indigenous mothers.

- In remote areas, smoking rates during pregnancy for First Nations mothers were 4.4 times as high as for non-Indigenous mothers. In non-remote areas, the rate of smoking during pregnancy for First Nations mothers was 3.7 times as high as for non-Indigenous mothers (Table D2.21.2).

Changes over time in smoking during pregnancy

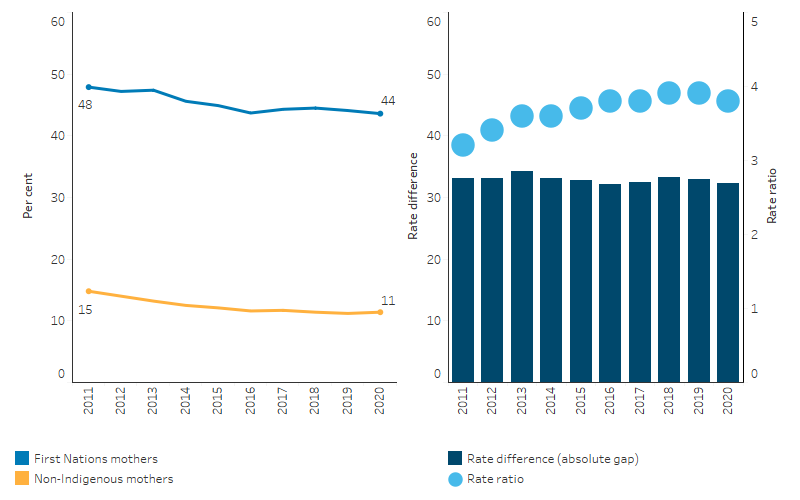

The proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked tobacco during pregnancy decreased from 50% in 2011 to 43% in 2020, based on crude rates (Table D2.21.20).

Based on age-standardised rates, the absolute reduction in rates of smoking during pregnancy was broadly similar for First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers (annual reductions of 0.5 and 0.4 percentage points, respectively, based on linear regression analysis), with little change in the gap between these rates. The absolute gap in the rates between the 2 populations ranged between 33 and 32 percentage points between 2011 and 2020 (Table 2.21.20, Figure 2.21.5).

Looking at percentage change over the period, using age-standardised rates, the proportion of First Nations mothers who smoked during pregnancy declined by 9.2%, based on linear regression analysis. For non-Indigenous mothers the proportion declined by 24.1% (Table D2.21.20).

Reflecting the higher percentage reduction for non-Indigenous mothers, the relative difference in the smoking rates of the 2 populations (as measured by the rate ratio) generally increased between 2011 and 2020. In 2011, the smoking rate among First Nations mothers was 3.2 times as high as for non-Indigenous mothers, compared with 3.8 times as high in 2020 (Table 2.21.20, Figure 2.21.5).

Figure 2.21.5: Age-standardised proportion of mothers who smoked during pregnancy and changes in the gap, Australia, by Indigenous status, 2011 to 2020

Source: Table D2.21.20. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Alcohol and drugs use during pregnancy

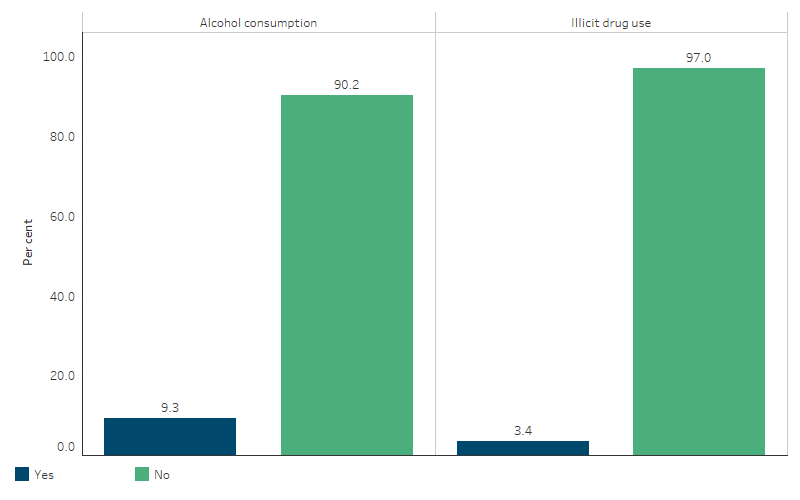

Based on self-reported data from the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, among mothers of First Nations children aged 0–3 in 2018–19, the vast majority did not consume alcohol (90%) and did not use illicit drugs (97%) during their pregnancy (Table D2.21.6, Figure 2.21.6).

Figure 2.21.6: Use of alcohol and illicit drugs during pregnancy, mothers of First Nations children (0–3 years), 2018–19

Source: Table D2.21.6. AIHW and ABS analysis of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19.

In the National Perinatal Data Collection, standardised data items on alcohol consumption during pregnancy were requested for the first time in 2019. The data items are currently voluntary – jurisdictions provide the data if possible, with a view to these items becoming mandatory in the future. In 2020, data were available for all jurisdictions except New South Wales. The National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines recommend that to prevent harm to their unborn child, women who are pregnant should avoid consuming alcohol (NHMRC 2020).

A survey of First Nations mothers’ drinking choices found that those who abstained from consuming alcohol during pregnancy reported doing so as they were aware of the responsibility to their developing baby and were supported by family and community. Building on these strengths in public health messaging and ensuring First Nations mothers have access to culturally safe and woman-centred antenatal care is key to reducing alcohol-related harm (Gibson et al. 2020). In 2020, again, the vast majority of First Nations mothers did not report consuming alcohol in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy or after 20 weeks – 92% in the first 20 weeks (excludes New South Wales), and 96% after 20 weeks (AIHW 2022a).

The rate of alcohol consumption among First Nations mothers was lower in the second 20 weeks of pregnancy than the first (3.6%, down from 8.2% in the first 20 weeks). The rate of alcohol consumption was higher among First Nations mothers than non-Indigenous mothers (8.2% compared with 2.4% in the first 20 weeks, and 3.6% compared with 0.6% after 20 weeks) (AIHW 2022a).

Because of differences in definitions and methods used for data collection, care must be taken when comparing across states and territories. Mothers’ alcohol consumption during pregnancy is self-reported.

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who reported consuming alcohol during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy was 10.3% in the Northern Territory (or 112 women), 9.8% in Queensland (420 women), 9.2% in Western Australia (162 women), 6.0% in South Australia (39 women) and 2.1% in Victoria (21 women) (Figure 2.21.7, Table D2.21.23).

The proportion of First Nations mothers who reported consuming alcohol after 20 weeks of pregnancy was 5.0% in the Northern Territory (53 women), 3.2% in Queensland (137 women), 5.4% in Western Australia (94 women), 4.1% in South Australia (27 women), and 1.5% in Victoria (15 women) (Figure 2.21.7, Table D2.21.24).

Figure 2.21.7: Alcohol consumption among First Nations mothers, Vic, Qld, WA, SA and NT, 2020

Note: Data for Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory not shown in figure due to relatively small numbers of First Nations mothers.

Source: Table D2.21.23 and D2.21.24. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Folate intake and other maternal health characteristics

Based on the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey, in 2014–15, 60% of mothers of First Nations children aged 0–3 took folate before or during their pregnancy. The proportion was highest in Inner regional areas (70%) and lowest in Very remote areas (33%) (Table D3.01.19).

According to data from the National Perinatal Data Collection, in 2020, among First Nations mothers:

- 36.5% had a normal body weight pre-pregnancy as indicated by their Body Mass Index (BMI), 57.2% were overweight or obese, and 6.3% were underweight

- 2.4% had pre-existing diabetes, and 14.8% had gestational diabetes

- 1.1% had pre-existing hypertension, and 3.0% had gestational hypertension (Table D2.21.12, Figure 2.21.8).

Figure 2.21.8: First Nations women who gave birth, by selected maternal characteristics, 2020

Source: Table D2.21.12. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Among women who gave birth in 2020, based on age-standardised rates, First Nations women, in comparison with non-Indigenous women, were:

- 1.6 times as likely to be classified as obese pre-pregnancy.

- 1.3 times as likely to be classified as underweight pre-pregnancy.

- 1.2 times as likely to have gestational diabetes.

- 3.5 times as likely to have pre-existing diabetes.

- 3.0 times as likely to have pre-existing hypertension (Table D2.21.12).

Research and evaluation findings

Effects of smoking on pregnancy

Tobacco smoking increases the risk of pregnancy complications (for example, miscarriage, placental abruption and premature labour) and poor perinatal outcomes such as low birthweight, intrauterine growth restriction, pre-term birth and perinatal death (England et al. 2004; Hodyl et al. 2014; Laws & Sullivan 2005; Pringle et al. 2015; Wills & Coory 2008). Maternal exposure to second-hand smoke also increases these risks for babies (Crane et al. 2011) (for effects of second-hand smoke exposure after birth (see measure 2.03 Environmental tobacco smoke). There is evidence that smoking cessation, particularly in the first trimester, can reduce these risks (Bickerstaff et al. 2012; Hodyl et al. 2014; Yan & Groothuis 2015).

Multivariate analysis of smoking and birth outcomes

Based on a multivariate analysis of singleton births for the period 2018–2020, smoking during pregnancy had the largest effect on birthweight (based on adjusted odds ratios) among other maternal characteristics included in the model. When accounting for the prevalence of mothers who smoked, an estimated 38% of low birthweight in First Nations babies was attributable to smoking during pregnancy (Table D1.01.8). If the smoking rate among mothers of First Nations babies was the same as that among mothers of non-Indigenous babies, the proportion of low birthweight First Nations babies could be reduced by 29% (see measure 1.01 Birthweight) (Table D1.01.8).

Separate multivariate analyses of 2018–2020 data looking at pre-term births and SGA births as outcomes indicate that, excluding multiple births:

- 21% of pre-term births of First Nations babies were attributable to smoking during pregnancy after adjusting for maternal age and other factors. It was estimated that if the rate of smoking during pregnancy among mothers of First Nations babies was the same as that among mothers of non-Indigenous babies, the proportion of babies that were pre-term could be reduced by 17%

- 40% of small-for-gestational age (SGA) births of First Nations babies were attributable to smoking during pregnancy. It was estimated that if the rate of smoking during pregnancy among mothers of First Nations babies was the same as that among mothers of non-Indigenous babies, the proportion of babies that were SGA babies could be reduced by 32% (see measure 1.01 Birthweight), (Tables D1.01.9 and D1.01.23).

Gibberd et al. (2019) found that a large proportion of adverse birth outcomes (SGA births, pre-term births, and perinatal deaths) among First Nations infants were attributable to the risk factors of tobacco use, alcohol consumption, drug use and assault of the mother (based on hospitalisation for assault over the period from giving birth back to 2 years prior to the start of pregnancy). Among 28,119 First Nations singleton infants born in Western Australia between 1998 and 2010:

- 16% of infants were SGA, 13% were pre-term, and 2% died in the perinatal period

- 51% of infants were exposed to at least one of the risk factors of smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use or assault of the mother

- 37% of SGA births, 16% of pre-term births and 20% perinatal deaths could be attributed to smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use or assault against the mother (combined)

- Maternal smoking was associated with over twice the odds of SGA birth, 26% higher odds of pre-term birth and 49% higher odds of perinatal death

- Alcohol use was associated with 118% higher odds of SGA and 83% higher odds of perinatal death, but the association with pre-term birth, while positive, was not statistically significant

- Drug misuse and assault were strongly associated with SGA and pre-term birth, but not perinatal death (Gibberd et al. 2019).

Efforts to reduce smoking among First Nations mothers

The HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies includes analysis of the impact of smoking on birthweight. This found that while the rate of maternal smoking is decreasing, it is not projected to decrease to the estimated level required to reduce the low birthweight rate to a level consistent with the healthy birthweight Closing the Gap target for 2031. Based on modelling work, at a national level and assuming other explanatory factors stay constant, it was estimated that the rate of maternal smoking among First Nations mothers would need to fall to about 27% by 2031 in order to meet the target (down from 44% in 2019).

First Nations women are motivated to stop smoking during pregnancy and are making attempts to quit (Colonna et al. 2020). A review of evidence on smoking among First Nations people found that knowledge about the direct and indirect health effects of smoking can be influential in changing behaviour including among pregnant women. First Nations women who quit smoking during pregnancy were found to have a better understanding of the health risks to their baby than those who continued smoking (Colonna et al. 2020). Another review by Harris et al. (2019) found that social and familial influences and stress levels have a strong impact on quitting smoking during pregnancy. However, information and advice regarding potential adverse effects of smoking on the baby, or lack thereof, from health professionals either facilitated smoking cessation or was a barrier to quitting. A lack of awareness of smoking cessation strategies among midwives and doctors was identified as a barrier to smoking cessation among First Nations pregnant women. Involving pregnant First Nations women’s partners, support people and family in education on the adverse effects of smoking and the benefits of smoking cessation strategies, may have a positive effect on attempts to stop smoking, as this can lead to the women being supported in their decision to quit. Additional professional development for health professionals to facilitate smoking cessation in a culturally competent manner is also needed (Harris et al. 2019).

In a national cross-sectional survey of First Nations women aged 16–49 who were smokers or ex-smokers, the study found that 36% have used nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and/or stop-smoking medications (SSM). Older women (35–49 years) were more likely to have sustained a quit attempt for years and to have tried NRT and/or SSM than younger women. Quitting smoking suddenly, rather than gradually reducing cigarette consumption, was significantly associated with sustained abstinence. Despite the willingness to quit, most women who had never used NRT or SSM cited reasons such as ‘wanting to quit on my own without help’, cost, and a preference not to use medications as the main reasons for not using NRT or SSM. The study emphasises the role of health providers in offering consistent cessation support and in providing a range of cessation options to clients (Kennedy et al. 2022).

A cross-sectional study was conducted among Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners from June to September 2021 (via survey) to explore workforce knowledge, attitudes, and practices in offering best practice smoking cessation care. Out of 1,052 registered Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners, 256 participants completed the full survey (24.3%). Of the survey participants, over one-half (57.6%) worked in ACCHSs. The survey results showed that smoking cessation counselling was always provided by 41.9%; provided some of the time by 42.4%, and never provided by 12.9%. Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners that had received training felt smoking cessation was part of their role, and those that were based in ACCHSs were more likely to offer best practice smoking cessation care. Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners that were based in ACCHSs were more likely to ‘always/often’ provide combination NRT compared to those that worked in other health settings or general practice. Smoking cessation training for Aboriginal Health Workers/Practitioners is often informal and unfunded despite the majority of these workers (76.5%) feeling that smoking cessation care is part of their role (Kennedy et al. 2023). The iSISTAQUIT program is one example of a training program that may help to improve smoking cessation training among health practitioners.

Communication strategies for smoking cessation

A review on tobacco use among First Nations women, found that there is a need to improve communication regarding the health effects of smoking during pregnancy. The review argues that effective anti-tobacco programs need to be culturally appropriate and expanded through long-term funding and rigorous evaluation (Colonna et al. 2020). Yarning circles conducted with First Nations women found that targeted resources on smoking cessation during pregnancy needed to be visually attractive and interactive, and include additional scientific content on the health consequences (Bovill et al. 2019). Developing effective health promotion materials requires more than a culturally appropriate adaptation of mainstream resources, and the diversity of First Nations communities needs to be considered when developing interventions.

Research has also recommended approaches that: consider social and environmental contexts; increase knowledge of harm and cessation methods; are tailored to clients’ needs; are provided in a way that does not cause embarrassment or distress or deter further antenatal care; are culturally targeted with First Nations health worker involvement; include partners, families and communities; are provided before, during and after pregnancy; and include alternative stress reduction and coping strategies (Bond et al. 2012; Bridge 2011; Elliott DJ & Silverman 2013; France et al. 2010; Gould et al. 2013; Marley et al. 2014; van der Sterren & Fowlie 2015; Wood et al. 2008).

Effects of alcohol (or other drugs) on pregnancy

The Australian guidelines to reduce health risks from drinking alcohol (2020) recommend that for women who are pregnant, planning a pregnancy or breastfeeding, not drinking alcohol is the safest option for the baby (NHMRC 2020). Drinking alcohol while pregnant may have consequences for fetal development of the brain and can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, low birthweight, intrauterine growth restriction and pre-term birth and has been shown to result in a range of potentially lifelong physical, mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental abnormalities and learning issues, collectively referred to as FASD (France et al. 2010; Mutch et al. 2015; Srikartika & O'Leary 2015).

Nationally, the prevalence of FASD for First Nations people is not known. A study in the Fitzroy Valley in Western Australia, where First Nations women led the way in developing the Marulu Strategy to deal with FASD, found rates to be 120 per 1,000 children (albeit based on a small sample size of 127 pregnancies) (Elliott et al. 2012; Fitzpatrick et al. 2015). While existing research has limitations, risks of harm are said to increase with the amount and frequency of alcohol consumed (O'Leary et al. 2010). Large, population-based studies are needed to strengthen the evidence base.

A community-led project to lower the risk of FASD in the Fitzroy Valley has achieved outstanding results. The project was guided by Elders and the evidence-based Marulu Strategy. It was developed in consultation with research partners the Telethon Kids Institute, the University of Sydney and the George Institute for Global Health. The intervention adopted a holistic approach to lower the risk and impact of FASD through prevention, diagnosis and providing therapy support to affected individuals and families coping with lifelong physical and mental health problems. A team of 20 local First Nations community researchers were trained and enlisted to run the program (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017; Telethon Kids Institute 2016). Since the Marulu Strategy began in 2010, midwife-collected data revealed a dramatic fall in drinking during pregnancy in the Fitzroy Valley in response to the program, from 61.0% in 2010 to 31.9% in 2015. This was heavily influenced by the significant reduction in first-trimester alcohol use from 45.1% in 2008 to 21.6% in 2015 (Symons et al. 2020). The project also teamed up with multidisciplinary paediatric and allied health services to provide FASD diagnosis and follow-up services to the participating communities. Between 2016 and 2018, the project provided a total of 209 assessments to children, youths and adults, and supported those in need by providing a total of 458 therapy hours. The project highlighted the value of community-led strategies (for example, educating the community on the harms of alcohol consumption during pregnancy) to reduce and eliminate FASD. These findings provide lessons for approaches in other First Nations and non-Indigenous communities.

There is limited research evidence on the effectiveness of implementation strategies to improve antenatal care that addresses the consumption of alcohol during pregnancy (Kingsland et al. 2018). A randomised trial in the Hunter New England Local Health District in New South Wales examined the effectiveness of changes to the model of care delivered by public antenatal services to improve the provision of care to address alcohol consumption during pregnancy. All aspects of the study design, from conception through to dissemination, were inclusive of First Nations people. This inclusivity was intended to inform the cultural inclusion, safety, and appropriateness of the intervention. Changes to the model of care included brief advice to abstain from alcohol and information about potential risks, with additional support services offered based on the level of alcohol consumption risk identified through the use of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) tool to assess the alcohol consumption of pregnant women. First Nations women identified as medium- or high-risk were offered a choice of referrals to First Nations-specific Drug and Alcohol Clinical Services or other culturally safe Drug and Alcohol Clinical Services, such as a local ACCHS. Pre-intervention surveys, based on previous national surveys and reviewed for cultural appropriateness, were completed by 1,309 women, and post-intervention surveys completed by 2,540 women. First Nations women were offered to be interviewed by a First Nations interviewer. The trial resulted in no change in the proportion of women classified as ‘No risk from drinking’ (AUDIT-C score = 0) or ‘Some risk from drinking’ (AUDIT-C score > 1) pre- or post-intervention. Special occasion drinking was observed to have a significant reduction (Tsang et al. 2022).

Research into the role that alcohol and other drug (AOD) treatment services play in preventing and addressing the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (PAE) was conducted in the Greater Newcastle region in Australia (Pedruzzi et al. 2021). The study concluded that providing family planning services and care to women post birth and through the early years of their child’s development helps address unplanned pregnancies and PAE before recognition of pregnancy. Implementing these initiatives “will likely have greater affects than any training or education initiatives concerning PAE” (Pedruzzi et al. 2021). The paper also argues for a systemic shift in the provision of AOD treatment services that is inclusive of women with children, and recognises the social barriers that affect women who are pregnant or have children and that prevent them from adopting healthy behaviours.

An Australian FASD Indigenous Framework was created to address health promotion and assessment of FASD in First Nations communities (Hewlett et al. 2023). The framework considers both First Nations people and clinicians, and what both parties need to know, be and do to address the current shortages in assessing, diagnosing and providing care to individuals and families living with FASD. Through researching the framework, the authors concluded that clinicians need to undo the legacies of colonisation and allow First Nations perspectives of history and health and wellbeing to be of equal value in the clinical setting. The research also identified the need for better understanding of FASD amongst First Nations people, as misunderstanding of behaviours, and stigma, prevent effective care and understanding being provided to individuals and families living with FASD.

Use of illicit drugs, such as heroin and cannabis, and unsafe use of licit drugs, such as medicines, during pregnancy can pose health risks to the mother (for example, overdose and accidental injuries) as well as significant obstetric, fetal and neonatal complications (Kennare et al. 2005; Kulaga et al. 2009; Ludlow et al. 2004; Wallace et al. 2007), and behavioural and cognitive problems that emerge in later life (Passey et al. 2014). Concurrent use of multiple substances and clustering of risk factors, particularly for women of lower socioeconomic status, also need to be considered and addressed through holistic approaches (Brown et al. 2016b; Eades et al. 2012; Passey et al. 2014; Wen et al. 2010).

Diabetes in pregnancy

Since colonisation, the lifestyle of First Nations people has undergone a rapid transition towards Western lifestyles over a relatively short period of time, and the prevalence of overweight/obesity has become high. In a retrospective cohort study using data linkage of all singleton births in Western Australia (using the Western Australian Data Linkage System), obesity had a stronger association with gestational diabetes in First Nations mothers compared to non-Indigenous mothers. The international literature has shown that gestational diabetes mellitus is the most common complication in pregnancy, and increases the risk of fetal overgrowth, respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal hypoglycaemia, pre-term birth, hyperbilirubinemia and polyhydramnios. Moreover, gestational diabetes has negative long-term implications for both the child and mother. In Australia, gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence is consistently higher among First Nations women. First Nations mothers were also more likely to: be younger, have higher parity, have smoked during pregnancy and live in remote/very remote areas. The likelihood of gestational hypertension, eclampsia/pre-eclampsia and adverse obstetric history events (such as previous events of: Large for Gestational Age (LGA), macrosomia, stillbirth and birth defects) were higher in First Nations mothers than in non-Indigenous mothers. Maternal obesity significantly increases the risk of pregnancy complications among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2023).

In a related study in Western Australia by the same authors, analysis was conducted on the impact of diabetes in pregnancy on trends for births that were LGA. The study found that between 1998 and 2015 the age-standardised rates of pre-gestational diabetes among First Nations mothers rose from 4.3% in 1998 to 5.4% in 2015 but remained below 1% among non-Indigenous women. Over the same period, rates of gestational diabetes rose from 6.7% to 11.5% for First Nations women, and from 3.5% to 10.2% for non-Indigenous women. Analysis highlighted that diabetes in pregnancy substantially contributed to increasing trends in LGA among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2022).

A systematic review of reported neonatal and pregnancy outcomes of First Nations mothers with diabetes in pregnancy identified that First Nations mothers and babies experienced higher rates of many known adverse outcomes of diabetes in pregnancy than non-Indigenous Australians including: macrosomia, caesarean section, congenital deformities, low birth weight, hypoglycaemia, and neonatal trauma (Duong et al. 2015).

Nutrition and exercise during pregnancy

The factors affecting First Nations people’s food and nutrition intake are complex. Food insecurity, often linked to the introduction of Western diets, limited access to traditional food sources, and the prohibitive expense of and lack of access to nutritious foods in many First Nations communities is an ongoing concern. Social determinants, including housing, education, economic status, and access to services all impact on health. First Nations people are disproportionately affected by food insecurity and socioeconomic determinants that can contribute to unhealthy food consumption patterns and development of diet-related chronic diseases. The Mums and Bubs Deadly Diets study aims to co-design a culturally appropriate digital tool to support the nutrition needs of First Nations women in pregnancy. The study has recruited First Nations women from Queensland, New South Wales and Western Australia, and health care professionals who support First Nations women during pregnancy. This new study is an iterative and adaptive research program that endeavours to develop real-world, impactful resources to support the nutrition needs and priorities of pregnant First Nations women in Australia (Gilbert et al. 2023).

Healthy nutrition before and during pregnancy is essential for fetal development (McDermott et al. 2009; Wen et al. 2010). Eating the recommended number of daily serves of the 5 food groups and drinking plenty of water is important during pregnancy. Maintenance of folate levels is particularly important to decrease the risk of neural tube defects such as spina bifida (AHMAC 2012), which in the past has been twice as common among babies born to First Nations women as those born to non-Indigenous women (data for New South Wales and Western Australia combined due to data quality issues) (Macaldowie & Hilder 2011). However, following mandatory flour fortification with folic acid in 2009 there have been reductions in neural tube defects among First Nations infants, and this has closed the gap with non-Indigenous infants in the rates of neural tube defects (D'Antoine & Bower 2019).

Sufficient iodine levels are particularly important for women of childbearing age as a deficiency could impede the normal growth and development of the fetus if these women were to become pregnant (WHO et al. 2007). The 2012–13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey measured the iodine levels of First Nations people using a urine test (ABS 2014). The results showed that nationally, First Nations women aged 18–44 were iodine sufficient in 2012–13, with a population median urinary iodine concentration (UIC) of 135.0μg/L. However, for pregnant and lactating women, the World Health Organization recommends a UIC level of 150 to 249μg/L (NHMRC 2009a). Research in the Top End of the Northern Territory in 2005–2008 found that young First Nations people were classified as mildly to moderately iodine deficient prior to the mandatory fortification of bread with iodised salt in Australia in 2009 (Mackerras et al. 2011). A subsequent research project compared the iodine status of young First Nations people in the Top End in 2006–2007 (prior to fortification) to iodine status in 2013–2015 (post-fortification) (Singh et al. 2019). An analysis of the results found that while the median UIC of the urban First Nations youth increased post-fortification, and this group achieved adequate iodine levels, young First Nations women from remote areas remained mildly iodine deficient. While the results suggested an increase in median UIC among the small group of pregnant young First Nations female participants post-fortification, their median UIC remained below the recommended minimum of 150μg/L for pregnant women.

Access to healthy food can be problematic due to geographical location and the high cost of fresh food in remote areas. The Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2012–13 found that around 22% of First Nations people had run out of food in the past year and could not afford to buy more, and for First Nations people in remote areas this was 31% (ABS 2015). Fresh produce is often less accessible in remote areas, and healthy food can cost up to 50% more in remote stores compared to capital cities (Christidis et al. 2021).

Exercise during pregnancy is beneficial for the mother and fetus during gestation, with benefits persisting for the child into adulthood. It is associated with a reduced risk of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and pre-term birth, as well as improved pain tolerance, lower total weight gain and less fat mass gain, and improved self-image. Exercise during pregnancy also decreases the risk of chronic disease for both mother and child (Moyer et al. 2016).

Community-based programs and services

iSISTAQUIT is an evidence-based and culturally competent smoking cessation training program for health practitioners who provide support and assistance to pregnant First Nations women in Australia. A study to scale up the implementation of the iSISTAQUIT intervention in First Nations-specific medical services and mainstream health services is underway. The project aims to practically apply and integrate a highly translatable smoking cessation intervention in real-world primary care settings. The intervention is based on accepted Australian and international smoking cessation guidelines, developed and delivered in a culturally appropriate approach for First Nations communities (Gould et al. 2022).

An evaluation of the Malabar service – a community‐based culturally appropriate service that addressed the antenatal care needs of First Nations women – found that the continuity of care was the most valued aspect of the service. The midwives, First Nations health education officers and nurses were seen as friendly, supportive, engaged, and approachable. The development of trust was a recurring theme during the evaluation (Homer et al. 2012). Malabar was considered to provide more than just a maternity service, with women stating that it also helped to establish social networks and play-groups. An evaluation of the Malabar service over the period 2007 to 2014 found a 25% reduction in the rates of smoking after 20 weeks gestation, but similar rates of pre-term birth and breastfeeding at discharge, and a higher rate of low birthweight babies, compared with mainstream services (Hartz et al. 2019). However, Malabar outcomes were better than state and national outcomes.

The Ynan Ngurra-ngu Walalja Halls Creek Community Families Program was a community-based maternal and child health education and prevention home visiting program for First Nations families (Walker 2010). Experienced First Nations mothers and grandmothers were trained as community care workers to provide a range of culturally appropriate activities, including home visiting support. A 2011 evaluation of the program found evidence of families reducing smoking around pregnant women and having an increased awareness of the influences of alcohol during pregnancy. The evaluation found the program to be culturally responsive and adapted to meet the specific needs of the local First Nations community.

A study into the spatial variation in First Nations women’s access to maternal health services found that poorer access to at least one maternal health service (hospitals with a public birthing unit; First Nations-specific primary health-care services; Royal Flying Doctor Service clinics; or general practitioners) was associated with higher smoking rates and higher rates of pre-term delivery and low birthweight. It also found that poorer access to First Nations-specific primary health care was associated with higher levels of smoking and low birthweight. In this study, one-fifth (20.5%) of First Nations women lived more than one hour from the nearest hospital with a public birthing unit, and 15% of First Nations women aged 15–44 lived more than one hour from a First Nations-specific primary health care service offering antenatal/maternal services. Access to at least one type of maternal health service was lowest for First Nations women in Remote and Very remote areas (AIHW 2017).

Culturally safe maternity services

Preconception care is emerging as an important part of public health efforts to improve maternal and child health. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recommends that every woman of reproductive age be considered for preconception care to identify and modify risks to a woman’s health or pregnancy (RACGP 2018). A study of preconception care in a Very remote ACCHS found a high proportion of women who had a pregnancy during the study period had received preconception care, but this was lower for younger women, particularly in screening for modifiable risk factors (Griffiths et al. 2020). The study suggests that ACCHSs can play an important role in supporting reproductive health literacy, particularly among younger women.

Although maternity services in Australia are designed to offer women the best care, they mostly reflect Western medical values and perceptions of health, risk, and safety. Achieving culturally safe maternity services is critical to improving health for First Nations mothers and babies (Kildea et al. 2016), and this is underpinned by cultural awareness among health professionals.

The Indigenous Birthing in an Urban Setting study (IBUS) was undertaken to study the effects of ‘Birthing on Country’ service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations people in Queensland. Research from the study focused on the clinical effectiveness of the "Birthing in Our Community (BiOC)" service, a partnership between the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane, and the Mater Mothers’ Hospital. A total of 1,422 women were included in the analysis who received either standard care (656 participants) or the BiOC service (766 participants) between 1 January 2013, and 30 June 2019. The results showed that women engaged with the BiOC service were more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal care visits, had a reduced likelihood of pre-term birth, and were more likely to exclusively breastfeed upon hospital discharge. However, there was no significant difference in smoking rates after 20 weeks of gestation. For the women engaged with the BiOC service there were also differences in labour care outcomes (such as fewer epidurals in the first stage of labour and fewer planned caesarean sections, being less likely to be admitted to a special neonatal care nursery or neonatal intensive care unit, and being more likely to have their third stage of labour managed without intervention) compared with those receiving standard care. The study concluded that the BiOC service, grounded in Birthing on Country principles, has demonstrated clinical effectiveness and resulted in significantly improved maternal and infant outcomes (Kildea et al. 2021).

The BiOC service offers a cost-effective alternative to Standard Care in reducing the proportion of pre-term births and cost savings per mother-baby pair. The cost savings were driven by less interventions and procedures in birth and fewer neonatal admissions. Investing in comprehensive, community-led models of care improves maternal and child health outcomes at reduced cost (Gao et al. 2023).

The Building On Our Strengths (BOOSt) prospective mixed-methods birth cohort study aims to facilitate and assess the expansion of 'Birthing on Country' services into 2 settings – urban Queensland and rural New South Wales. These services are designed to be community-based and governed, allowing for the incorporation of traditional practices and a connection with land and country. The services offer integrated, holistic care, including continuity of care from primary through to tertiary services, and in safe and supportive spaces. Once published, the analysis will measure the feasibility, acceptability, clinical and cultural safety, effectiveness and cost of the services (Haora et al. 2023).

The evaluation of the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) found that the program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy, growth, and empowerment. Three main themes were generated: 1) sustaining connections and relationships; 2) developing self-belief and personal skills; and 3) achieving transformation and growth. When the program facilitates the development of culturally safe relationships with staff and peers, it enables behaviour change, skill development, personal goal setting and achievement, leading to self-efficacy. Located within a community-controlled health service, the program can foster cultural connection, peer support and access to health and social services; all contributing to self-efficacy (Massi et al. 2023). However, although the ANFPP has strengths, the impact on low birthweight or smoking during pregnancy among participant mothers was not evident between 2017–18 and 2020–21 (ANFPP Support Service 2021).

Implications

A key component of improving pregnancy outcomes is early and ongoing engagement in culturally safe antenatal care, which is facilitated by the provision of culturally appropriate and evidence-based care that is led by and relevant to the local community (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Strategies addressing potentially modifiable risk factors (such as smoking, alcohol and substance use) as well as fostering positive health behaviours (such as healthy diet and exercise) should be a primary focus of antenatal care delivery. Community awareness campaigns are essential.

The HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies presents more detailed statistical analysis on low birthweight including trend analysis of gestational age (pre-term, early-term, full-term births), birthweight and key contributing factors such as maternal health, smoking during pregnancy and antenatal care attendance. It also provides analysis of the level of improvement required in smoking rates to meet the birthweight target in the National Agreement. The inclusion of alcohol consumption during pregnancy is a useful addition to the National Perinatal Data Collection, from 2019, that will aid the analysis of maternal risks and birth outcomes in coming years.

Women who are healthy before and during pregnancy are more likely to have a healthy baby. Approaches that can lead to better outcomes for First Nations women and their babies include improving access to maternal health services for women in remote and very remote areas and enabling access to culturally appropriate health care in both First Nations community-controlled and mainstream health services (Boyle & Eades 2016; Gibson-Helm et al. 2016).

The Australian Government has allocated funding from 2021–22 to 2024–25 to extend the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) at 13 existing locations and introduce it to 2 new areas in Western Australia. The ANFPP, tailored for First Nations communities, offers home visits by nurses to women expecting a First Nations child, supporting them from pregnancy until the child is 2 years old. It also funds several initiatives to enhance antenatal care and health behaviours for First Nations women during pregnancy, including: Baby coming you ready; National Pre-term Birth Prevention Program; and the Women-centred care strategy.

Protective factors such as not smoking during pregnancy and the enhancement of self-efficacy among mothers (related to social and emotional wellbeing and connection to the community) contribute to positive perinatal health outcomes (Westrupp et al. 2019). Research suggests that culturally safe and appropriate antenatal care delivered in partnership with ACCHSs achieves better outcomes for women giving birth to First Nations babies compared with standard care (Kildea et al. 2019). More regional-level data on risk factors will assist in targeting interventions, such as using locally adapted approaches to smoking cessation (Westrupp et al. 2019).

Partnerships between ACCHSs and mainstream services can help address the long-held issues around mistrust of mainstream health services (Rumbold & Cunningham 2007) and improve the quality of antenatal care (Campbell et al. 2018). First Nations community-led prevention and intervention strategies have been shown to be an effective approach. While progress has been made to strengthen maternity services to support the provision of culturally competent care, build the First Nations maternity workforce and increase Birthing on Country, more effort is needed in these areas (Kildea et al. 2016). An analysis of areas that lack access to ACCHSs for maternal and child health care is an urgent necessity.

Preconception care, including improving reproductive health literacy, typically through primary health care providers, can be an important avenue to address risk factors for women of reproductive age. However, time constraints and competing priorities for preventative health in the primary health care setting may mean preconception care is underutilised, particularly among First Nations women at the younger and older ends of reproductive age. Integrating preconception care into existing clinical practice with existing Medicare items such as health assessments and chronic disease management would provide more opportunities for brief interventions (Griffiths et al. 2020).

Enhanced primary care services and continued improvement in, and access to, culturally appropriate antenatal care have the capacity to support improvements in the health of the mother and baby. This highlights the important role ACCHSs have in leading culturally safe and responsive health care within their communities (Panaretto et al. 2014). ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. The Australian Government committed to building a strong and sustainable First Nations community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people across the country under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement. Further work to ensure mainstream services can provide culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations people is also critically important and relates to Priority Reform Three of the National Agreement. These 2 dimensions of health care for First Nations people have been emphasised in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course.

The Health Plan, released in December 2021, is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap Priority Reforms and health targets. Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths-based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure a strong start to life. Comprehensive, wrap-around, community-led Birthing on Country services have the potential to support healthy pregnancies by offering an integrated, holistic and culturally safe model of care (Department of Health 2021).

Research has shown that Birthing on Country (BoC) models of care, which offer culturally safe, continuous midwifery care for First Nations women, improve birth outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies (such as improving frequency of antenatal care visits and reducing the likelihood of pre-term birth). The Australian Government is actively promoting the BoC model, especially in rural and remote areas where birthing outcomes can be challenging. To support this, the Australian Government has committed $32.2 million over 4 years (2021–22 to 2024–25) under the Healthy Mums, Healthy Bubs initiative to enhance the maternity health workforce and BoC practices. Additional funding ($22.5 million) has also been allocated over 3 financial years (2022–23 to 2024–25) for the establishment of a BoC Centre of Excellence at Waminda in Nowra, New South Wales. The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) also funded The Birthing on Country: RISE SAFELY study with $5 million, which will establish exemplar BoC services in 3 rural, remote and very remote settings. The study is First Nations-led, co-designed and staffed. More broadly, the Department of Health and Aged Care is partnering with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to develop a maternal and child health model of care to enable First Nations mothers and families to access consistent, culturally safe and effective care (NIAA 2023).

The National Tobacco Strategy 2023–2030 is an Australian Government initiative aimed at reducing smoking rates including among First Nations people, identified as a priority group. The Australian Government is also investing in a range of specific initiatives aimed at reducing smoking among First Nations peoples. The Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program aims to improve the life expectancy of First Nations peoples in Australia by reducing tobacco use, a major preventable cause of ill health in these communities. The program empowers local organisations to design evidence-based and measurable activities to lower smoking rates and prevent the initiation of smoking. Special emphasis is placed on supporting regional and remote areas through culturally tailored preventative population health activities in community settings. The program also funds educational campaigns to promote smoke-free community spaces and supports First Nations organisations working with pregnant mothers in remote areas. iSISTAQUIT uses a culturally safe model of care providing best practice training in smoking cessation for health professionals and encouragement to communities and pregnant women to quit smoking.

The Australian Government launched the National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan 2018–2028 on 21 November 2018. The plan provides 4 priority areas to address FASD in Australia. The plan focuses on prevention strategies, screening and diagnosis needs, support and management of FASD, and supporting priority groups at increased risk. The plan has been implemented with significant funding, and recently had its 3 year review completed. The review found there was a need for: greater cross-jurisdictional sharing of information; FASD training for health professionals; and better access to screening, diagnosis and support for those in the education and criminal justice sectors.

The Australian Government-funded National FASD Program aims to raise awareness among Australians about the risks of alcohol consumption during pregnancy and breastfeeding, including FASD. The program is structured into 4 streams, with ‘Stream 4’ specifically focused on First Nations people. The Strong Born Campaign, developed by NACCHO in collaboration with the National FASD Campaign Working Group, is a key initiative within Stream 4. The Strong Born Campaign looks to address and raise awareness of FASD and the harms of drinking alcohol while pregnant and breastfeeding in rural and remote areas of Australia, and collaborates with ACCHSs to target First Nations communities. The Strong Born Campaign includes culturally appropriate health information for women and families, educational materials for First Nations health care workers, and guidance for health care providers that work with First Nations communities to ensure a holistic and culturally safe model of health promotion is provided to all. Additionally, it supports individuals with FASD and their families by informing them about available services and resources.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2014. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Biomedical Results 2012–13. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS 2015. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Nutrition Results–Food and Nutrients 2012-13. Cat. no. 4727.0.55.005. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS & AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2008. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2008. Canberra: ABS & AIHW.

- AHMAC 2012. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. (ed., Department of Health and Ageing). Canberra: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

- Ahmed MA, Bailey HD, Pereira G, White SW, Hare MJL, Wong K et al. 2023. Overweight/obesity and other predictors of gestational diabetes among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in Western Australia. Preventive Medicine Reports 36:102444.

- Ahmed MA, Bailey HD, Pereira G, White SW, Wong K & Shepherd CCJ 2022. Trends and burden of diabetes in pregnancy among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal mothers in Western Australia, 1998–2015. BMC Public Health 22:263.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Headline indicators for children's health, development and wellbeing 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017. Spatial Variation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Access to 4 Types of Maternal Health Services. Canberra AIHW.

- AIHW 2020. Resources for supporting psychosocial health in pregnancy. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 7 October 2020.

- AIHW 2022a. Australia's mothers and babies. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022b. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework: Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies, IHPF 10. Canberra: AIHW.

- ANFPP (Australian Nurse Family Partnership Program) Support Service 2021. National Annual Data Report 1 July 2020 - 30 June 2021. Brisbane.

- Bickerstaff M, Beckmann M, Gibbons K & Flenady V 2012. Recent cessation of smoking and its effect on pregnancy outcomes. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 52:54-8.

- Bond C, Brough M, Spurling G & Hayman N 2012. ‘It had to be my choice’ Indigenous smoking cessation and negotiations of risk, resistance and resilience. Health, Risk & Society 14:565-81.

- Bourke S, Wright A, Guthrie J, Russell L, Dunbar T & Lovett R 2018. Evidence Review of Indigenous Culture for Health and Wellbeing. International Journal of Health, Wellness & Society 8:11-27.

- Bovill M, Bar-Zeev Y, Gruppetta M, Clarke M, Nicholls K, O'Mara P et al. 2019. Giri-nya-la-nha (talk together) to explore acceptability of targeted smoking cessation resources with Australian Aboriginal women. Public Health 176:149-58.

- Boyle J & Eades S 2016. Closing the gap in Aboriginal women's reproductive health: some progress, but still a long way to go. The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 56(3):223-4.

- Bridge P 2011. Ord Valley Aboriginal Health Service’s fetal alcohol spectrum disorders program: Big steps, solid outcome. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin 11.

- Brown S, Mensah FK, Ah Kit J, Stuart-Butler D, Glover K, Leane C et al. 2016a. Aboriginal Families Study Policy Brief No 4: Improving the health of Aboriginal babies. Melbourne: MCRI.

- Brown S, Mensah FK, Ah Kit J, Stuart-Butler D, Glover K, Leane C et al. 2016b. Use of cannabis during pregnancy and birth outcomes in an Aboriginal birth cohort: a cross-sectional, population-based study. BMJ Open 6:e010286.

- Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

- Christidis R, Lock M, Walker T & Browne J 2021. Concerns and priorities of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples regarding food and nutrition: a systematic review of qualitative evidence. Int J Equity Health 20.

- Clarke M & Boyle J 2014. Antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australian Family Physician 43:20-4.

- Colonna E, Maddox R, Cohen R, Marmor A, Doery K, Thurber K et al. 2020. Review of tobacco use among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

- Crane JM, Keough M, Murphy P, Burrage L & Hutchens D 2011. Effects of environmental tobacco smoke on perinatal outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 118:865-71.

- D'Antoine H & Bower C 2019. Folate status and neural tube defects in Aboriginal Australians: the success of mandatory fortification in reducing a health disparity. Current developments in nutrition 3:nzz071.

- Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2021–2031. Government of Australia.

- Duong V, Davis B & Falhammar H 2015. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in Indigenous Australians with diabetes in pregnancy. World journal of diabetes 6:880.

- Eades S, Read AW, Stanley FJ, Eades FN, McCaullay D & Williamson A 2008. Bibbulung Gnarneep ('solid kid'): causal pathways to poor birth outcomes in an urban Aboriginal birth cohort. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 44:342-6.

- Eades S, Sanson-Fisher RW, Wenitong M, Panaretto K, D'Este C, Gilligan C et al. 2012. An intensive smoking intervention for pregnant Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: a randomised controlled trial. The Medical Journal of Australia 197:42-6.

- Elliott, Latimer J, Fitzpatrick JP, Oscar J & Carter M 2012. There's hope in the valley. Journal of paediatrics and child health 48:190-2.

- Elliott D & Silverman M 2013. Why music matters: philosophical and cultural foundations. In: MacDonald R, Kreutz G & Mitchell L (eds). Music, Health and Wellbeing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- England LJ, Levine RJ, Qian C, Soule LM, Schisterman EF, Yu KF et al. 2004. Glucose tolerance and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus in nulliparous women who smoke during pregnancy. The American Journal of Epidemiology 160:1205-13.

- Fitzpatrick JP, Latimer J, Carter M, Oscar J, Ferreira ML, Carmichael Olson H et al. 2015. Prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome in a population-based sample of children living in remote Australia: the Lililwan Project. Journal of paediatrics and child health 51:450-7.

- France K, Henley N, Payne J, D'Antoine H, Bartu A, O'Leary C et al. 2010. Health professionals addressing alcohol use with pregnant women in Western Australia: barriers and strategies for communication. Substance Use & Misuse 45:1474-90.

- Gao Y, Roe Y, Hickey S, Chadha A, Kruske S, Nelson C et al. 2023. Birthing on country service compared to standard care for First Nations Australians: a cost-effectiveness analysis from a health system perspective. The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific.

- Gibberd A, Simpson JM, Jones J, Williams R, Stanley F & Eades SJ 2019. A large proportion of poor birth outcomes among Aboriginal Western Australians are attributable to smoking, alcohol and substance misuse, and assault. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 19.

- Gibson-Helm M, Bailie J, Matthews V, Laycock AF, Boyle J & Bailie RS 2016. Priority evidence-practice gaps in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal health care final report: engaging stakeholders in identifying priority evidence-practice gaps and strategies for improvement in primary health care (ESP project). Menzies School of Health Research.

- Gibson S, Nagle C, Paul J, McCarthy L & Muggli E 2020. Influences on drinking choices among Indigenous and non-Indigenous pregnant women in Australia: A qualitative study. PloS one 15:e0224719-e.

- Gilbert S, Irvine R, D'or M, Adam MTP, Collins CE, Marriott R et al. 2023. Indigenous Women and Their Nutrition During Pregnancy (the Mums and Bubs Deadly Diets Project): Protocol for a Co-designed Health Resource Development Study. JMIR Res Protoc.

- Gould G, Kumar R, Ryan N, Stevenson L, Oldmeadow C, La Hera Fuentes G et al. 2022. Protocol for iSISTAQUIT: Implementation phase of the supporting indigenous smokers to assist quitting project. PloS one.

- Gould G, Munn J, Watters T, McEwen A & Clough A 2013. Knowledge and views about maternal tobacco smoking and barriers for cessation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 15:863-74.

- Griffiths E, Marley JV & Atkinson D 2020. Preconception Care in a Remote Aboriginal Community Context: What, When and by Whom? International journal of environmental research and public health 17:3702.

- Haora P, Roe Y, Hickey S, Gao Y, Nelson C, Allen J et al. 2023. Developing and evaluating Birthing on Country services for First Nations Australians: the Building On Our Strengths (BOOSt) prospective mixed methods birth cohort study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23:77-.

- Harris B, Harris M, Rae K & Chojenta C 2019. Barriers and facilitators to smoking cessation within pregnant Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander women: An integrative review. Midwifery 73:49-61.

- Hartz DL, Blain J, Caplice S, Allende T, Anderson S, Hall B et al. 2019. Evaluation of an Australian Aboriginal model of maternity care: The Malabar Community Midwifery Link Service. Women and Birth 32:427-36.

- Hewlett N, Hayes L, Williams R, Hamilton S, Holland L, Gall A et al. 2023. Development of an Australian FASD Indigenous Framework: Aboriginal Healing-Informed and Strengths-Based Ways of Knowing, Being and Doing. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20:5215.