Key messages

- Regular antenatal care that commences early in pregnancy has been found to have a positive effect on health outcomes for mothers and babies. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) mothers, access to culturally sensitive and competent antenatal care is paramount.

- From 2012 to 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy increased from 50% to 71%.

- After adjusting for the differences in age structure between the two populations, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy in 2020 was 8.4 percentage points lower than for non-Indigenous mothers.

- In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who had their first antenatal visit in the first trimester of pregnancy was highest in Outer regional and Inner regional areas (each 74%) and was lowest in Remote areas (64%).

- First Nations mothers who had attended 5 or more antenatal visits during the course of their pregnancy were less likely to have a pre-term baby in 2020 (7.8%) than those who attended less than 5 visits or no antenatal care during pregnancy (20.7%).

- In 2020, First Nations women who gave birth and had their first antenatal care visit during the first trimester of pregnancy were less likely to have a baby of low birthweight (9.2%), compared with those who either had their first visit at 20 weeks or more gestation or did not have any antenatal care during pregnancy (14.0%).

- In a study involving 344 women who gave birth to a First Nations baby in South Australia between July 2011 and June 2013, 36% of women receiving mainstream public care described their antenatal care as ‘very good’ compared with 65% of women attending an Aboriginal Health Service, 63% of women receiving care from a metropolitan Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (AFBP), 54% of women attending a regional AFBP service, and 53% of women receiving care from a midwifery group practice.

- A 2012 evaluation found women who attended the Murri Antenatal Clinic, a specialist antenatal clinic for First Nations women, were less likely to experience perineal trauma, undergo an elective caesarean operation or have a baby admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit.

- Strategies addressing potentially modifiable risk factors for pre-term birth, low birthweight and small for gestational age babies should be an important focus of antenatal care delivery. An analysis of the clinical effectiveness of the Birthing in Our Community service (BiOC), an Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service (ACCHS) initiative, for women who gave birth to a First Nations baby found that women who received the BiOC service were less likely than women receiving standard care to give birth to a pre-term infant.

- A vast majority of deaths in infants occur in the first month of life and a key determinant is low birth weight. Well run Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) for maternal and child health in Australia have been shown to improve birthweights and antenatal care attendance, and significantly lower perinatal mortality. A number of such services exist but the extent and distribution of service gaps for these services is not known.

- Reviews of the literature have identified the following key success factors in First Nations maternal health programs: a safe and welcoming environment; outreach and home visiting; flexibility in service delivery and appointment times; access to transport; continuity of care and carer integration with other services (for example, ACCHSs or hospital); a focus on communication, relationship building and trust; involvement of women in decision-making; respect for First Nations culture; respect for privacy, dignity, and confidentiality; family involvement and childcare; appropriately trained workforce; First Nations staff and female staff; informed consent and right of refusal; tools to measure cultural competency.

Why is it important?

Antenatal care is the professional health care provided to mothers during pregnancy to ensure the best health conditions for both mother and baby. Antenatal care includes risk identification, prevention and management of pregnancy-related or concurrent diseases, health education and health promotion (AHMAC 2012; WHO 2016). Regular antenatal care that commences early in pregnancy has been found to have a positive effect on health outcomes for mothers and babies (AHMAC 2012; Arabena et al. 2015; Eades 2004). Well-managed discharge processes and programs that continue after birth have also shown benefits for child health, development and family wellbeing (Sivak et al. 2008).

Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) women have healthy pregnancies (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Health is a holistic concept for First Nations people, with social and emotional wellbeing as well as cultural, ecological and spiritual aspects viewed as the foundation of physical and mental health (Bourke et al. 2018; Verbunt et al. 2021). As such, the health and wellbeing of an individual is linked to the wellbeing of their family, community, environment, and culture (Bourke et al. 2018). First Nations cultures have many strengths that provide a positive influence on wellbeing and resilience for First Nations women and their families. These include a supportive extended family network and kinship, connection to Country and cultural practices such as languages, art, and music. For women who experience adverse events in their pregnancies, the factors that influence these outcomes can be diverse, reflecting a range of the social determinants of health as well as health behaviours and biomedical risks. These include:

- socioeconomic factors: lower income, higher unemployment, lower educational levels, inadequate infrastructure (for example, affordable housing and water supply), and lack of access to culturally safe health services (including maternal health services – particularly for those living in rural and remote areas), affordable healthy food and transportation options

- health factors: diabetes, cardiovascular disease (including rheumatic heart disease), respiratory disease, kidney disease, anaemia, communicable infections, injuries, poor mental health, and being overweight or underweight

- protective/risk factors: physical activity, food security and nutrition, harmful alcohol and other drug use, smoking and higher psychosocial stressors (for example, deaths in families, violence, serious illness, financial pressures and contact with the justice system).

In addition, racism, and other upstream determinants including the pervasive effects of colonisation, constitutes a ‘double burden’ for First Nations people, affecting their health and access to adequate and timely health care services (Kildea et al. 2016).

Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and their culture. This history and the ongoing impacts of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and poorer outcomes for First Nations people (Productivity Commission 2023). For First Nations people, factors such as cultural identity, family and kinship, Country and caring for Country, knowledge and beliefs, language and participation in cultural activities and access to traditional lands are also key determinants of health and wellbeing. These factors are interrelated and combine to affect the health of individuals and broader communities (AIHW 2022).

Providing culturally safe continuity of care and addressing risk factors such as maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy (see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy); attendance at antenatal care; and addressing maternal nutritional status, illness during pregnancy, pre-existing high blood pressure and diabetes, and socioeconomic disadvantage; can lead to improved outcomes for First Nations women and babies (ABS & AIHW 2008; AIHW 2011; Brown et al. 2016b; Eades et al. 2008; Khalidi et al. 2012; Panaretto et al. 2014; Sayers & Powers 1997).

The literature suggests that one way to improve outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies is through improved access to, and take up of, antenatal care services (AIHW 2014). Australian government funded antenatal care programs led by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) for First Nations women have been shown to have an impact on maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, and maternal nutrition and breastfeeding practices, which can in turn reduce the rates of low birthweight, pre-term birth, and child mortality (AIHW 2014). The ACCHS sector plays a significant role in providing comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people, including antenatal programs which have delivered improved outcomes for maternal and child health (Panaretto et al. 2007; Panaretto et al. 2014).

Culturally sensitive and competent antenatal care is paramount for First Nations women, acknowledging and respecting their unique cultural, spiritual, and social needs (Kildea et al. 2016). This includes the involvement of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Workers and Practitioners, Hospital Liaison Officers and non-Indigenous staff who have undergone training in the provision of care in culturally safe environments. Psychosocial stressors and institutional racism are significant barriers to accessing health care and have been consistently associated with adverse health outcomes for First Nations people (Peiris et al. 2008). Comprehensive mental health support should be integrated into antenatal care, recognising the increased vulnerability to mental health issues during pregnancy (Austin et al. 2013), which may be exacerbated by the unique stressors faced by First Nations women. Furthermore, antenatal care should extend beyond the individual, promoting the active involvement of family and community, which are central to First Nations cultures and vital for the holistic wellbeing of both mother and child (Panaretto et al. 2005).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Organisations (the Coalition of Peaks). The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including through working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision making by First Nations communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: By 2031, Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation (with infant and child mortality as supporting indicators)

- Target 2: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies with a healthy birthweight to 91 per cent (with supporting indicators on the use of antenatal care by pregnant women).

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement.

‘Healthy babies and children (Age range: 0–12)’ is one of the key life course phases focused on in the Health Plan, and 2 objectives specifically address this age range:

- Objective 4.2. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy babies.

- Objective 4.3. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy children.

Both the National Agreement and the Health Plan are discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Data findings

Regular antenatal care in the first trimester (before 14 weeks gestational age) is associated with better maternal health in pregnancy, fewer interventions in late pregnancy and positive child health outcomes.

Based on analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection, of 14,187 First Nations mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation in 2020:

- 71% (10,027) accessed their first antenatal care services (antenatal visit) during the first trimester (less than 14 gestational weeks) of their pregnancy

- 14% (1,923) attended their first antenatal visit after the first trimester but before 20 weeks

- 16% (2,237) attended first antenatal visit at 20 weeks or more or did not attend any visit during pregnancy (Table D3.01.10).

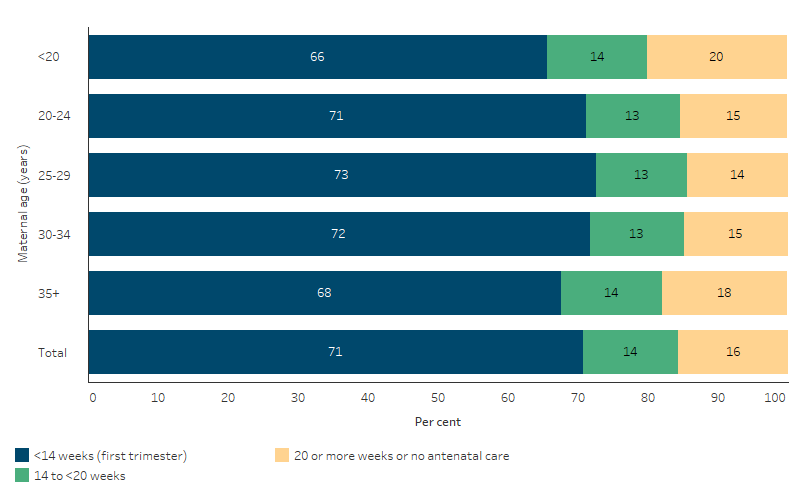

In 2020, First Nations mothers aged 25–29 were the most likely to attend antenatal care during the first trimester of their pregnancy, with nearly three-quarters (73% of 4,216 mothers) attending. This was followed closely by those aged 30–34 (72% of 2,685), 20–24 (71% of 4,194) and those aged 35 and over (68% of 1,511). First Nations mothers aged under 20 were the least likely to attend antenatal care in the first trimester (66% of 1,578) but were the most likely to attend at 20 weeks or more or to not attend at all (20%) (Table D3.01.12, Figure 3.01.1).

Figure 3.01. 1: Proportion of First Nations women who gave birth in 2020, by duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visit and age of the mother

Source: Table D3.01.12. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Comparing First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, First Nations mothers were less likely to attend their first antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy, equally likely to attend after the first trimester but before 20 weeks of pregnancy, and were more likely to attend their first antenatal visit at or after 20 weeks of gestation, or had no visit at all. In 2020, after adjusting for differences in age structure between the two populations, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal visit:

- in the first trimester was 8.4 percentage points lower than for non-Indigenous mothers (69.4% compared with 77.8%)

- after the first trimester but before 20 weeks was 0.6 percentage points higher than for non-Indigenous mothers (13.9% compared with 13.3%)

- at or after 20 weeks gestation or did not receive any antenatal care was 7.8 percentage points higher than for non-Indigenous mothers (16.8% compared with 8.9%) (Table D3.01.10).

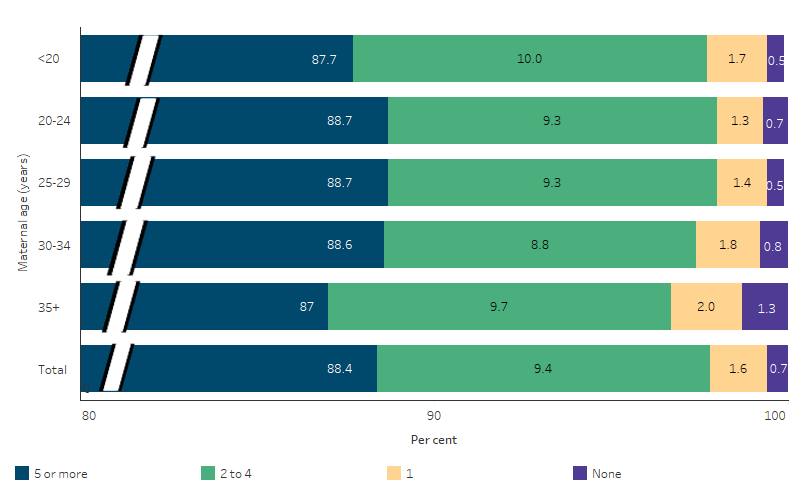

In 2020, about 9 in 10 (of 13,820) First Nations mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation attended 5 or more antenatal visits throughout their pregnancy (88.4% or 12,215), 9.3% (1,292) attended 2–4 visits, 1.6% (215) attended one visit and 0.7% (98) attended no visits. Nearly all (99.3%) attended at least once during pregnancy (Table D3.01.1).

These proportions did not vary by mothers’ age groups (Table D3.01.3, Figure 3.01.2).

Figure 3.01.2: Proportion of First Nations women who gave birth in 2020 at 32 weeks or more gestation, by number of antenatal visits and age of the mother

Note: // indicates a break in the axis to enable easier comparisons between age groups where proportions of First Nations women attending antenatal visits were less than 5%.

Source: Table D3.01.3. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Antenatal care by remoteness area, jurisdiction, and age

In this section, data on the duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit refers to mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, while data on the number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy refers to mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation (see also Box 3.01.1).

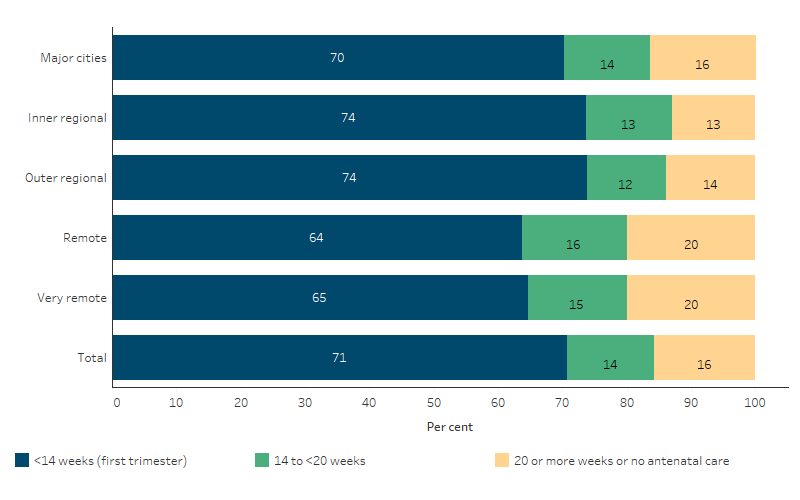

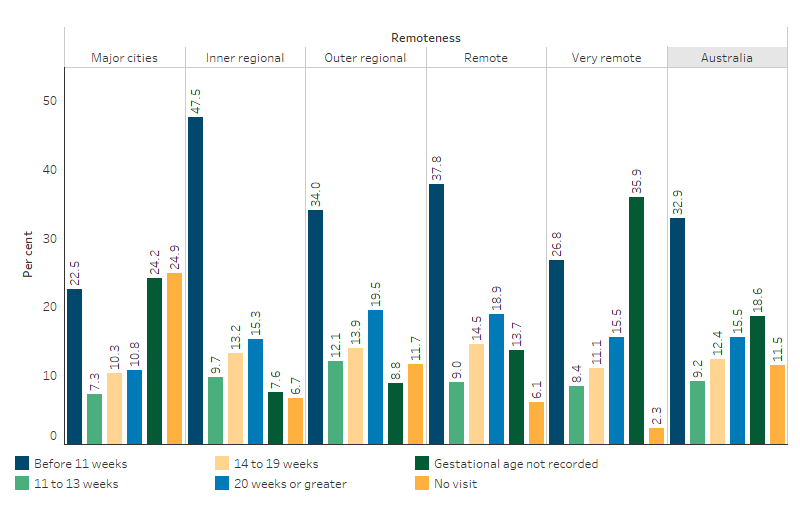

In 2020, First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal visit in the first trimester of pregnancy were less likely to be living in remote areas (64%, Remote and very remote areas combined) than in non-remote areas (72%, Major cities, outer regional, and inner regional areas combined). The proportions of First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal visit in the first trimester of pregnancy was highest in Inner regional and Outer regional areas (each 74%), followed by Major cities (70%) and Very remote areas (65%), and was lowest in Remote areas (64%).

One-fifth (20%) of First Nations mothers living in Remote or Very remote areas had attended their first antenatal visit at 20 weeks or more gestation, or did not attend antenatal care at all, compared with 15% of those living in non-remote areas (16% in Major cities, 14% in Outer regional areas, and 13% in Inner regional areas) (Table D3.01.11, Figure 3.01.3).

In 2020, compared with all First Nations mothers who gave birth, a higher proportion of First Nations mothers who had their first antenatal care visit later in pregnancy, or had no antenatal care, lived in remote areas or were aged under 20. Of First Nations mothers who gave birth in 2020, and attended their first antenatal visit at 20 weeks or more gestation, or received no antenatal care during pregnancy:

- nearly one-quarter (24%, 524 of 2,222) lived in remote areas (Remote and very remote areas combined), despite only 18% (2,648 of 14,323) of all First Nations mothers who gave birth living in remote areas (Table D3.01.11)

- 14% (316 of 2,237) were aged under 20, despite only 11% (1,608 of 14,381) of all First Nations mothers who gave birth being aged under 20 (Table D3.01.12).

Based on age-standardised data, the proportion of First Nations mothers attending antenatal care in the first trimester was lower than for non-Indigenous mothers. While this was consistent across both non-remote (Major cities, inner regional and outer regional areas combined) areas and remote areas (Remote and very remote areas combined), the absolute gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers was larger in remote areas (13.8 percentage points) than in non-remote areas (7.1 percentage points) (Table D3.01.11).

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation and had attended 5 or more antenatal visits during their pregnancy was 85% in Remote areas, compared with about 89% in each of the other remoteness areas (Major cities, Inner regional areas, Outer regional areas, and Very remote areas) (Table D3.01.2).

Figure 3.01.3: Proportion of First Nations women who gave birth in 2020, by timing of first antenatal visit and remoteness

Source: Table D3.01.11. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

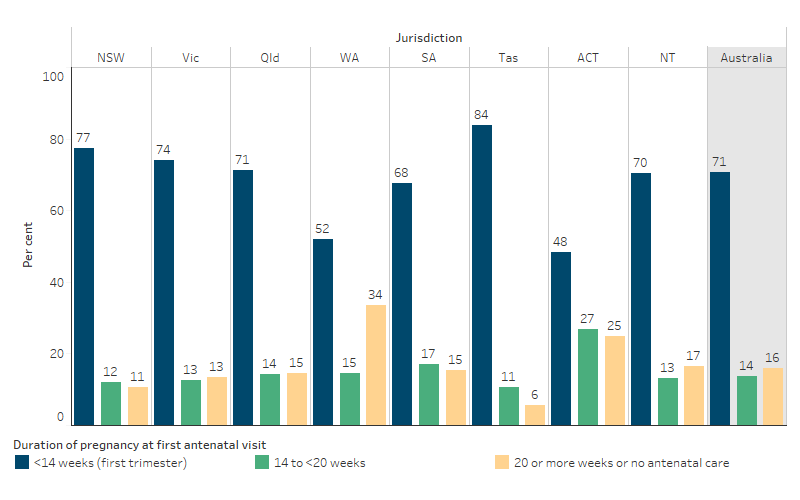

The proportion of First Nations mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation and who had their first antenatal visit in the first trimester of pregnancy varied across states and territories, ranging from 48% (Australian Capital Territory) to 84% (Tasmania) in 2020 (Figure 3.01.4, Table D3.01.10).

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal visit at 20 weeks or more gestation, or had no antenatal visit at all, was highest in Western Australia (33.5%), and lowest in Tasmania (5.5%). Of the 2,237 First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal visit at 20 weeks or more gestation, or received no antenatal care during pregnancy, 27% (614) lived in Western Australia. For comparison, only 13% of all First Nations women who gave birth in 2020 lived in Western Australia (Table D3.01.10).

However, care should be taken when comparing these data across jurisdictions due to differences in definitions and methods. For example, in Western Australia, gestational age at first antenatal visit is reported by birth hospital and data may not be available for women who attend their first antenatal visit outside the birth hospital. For the Australian Capital Territory, in many cases early antenatal care provided by a woman’s general practitioner is not reported. Populations within states and territories also differ in their distribution by remoteness areas, which may also affect these comparisons.

Figure 3.01.4: Proportion of First Nations women who gave birth in 2020, by timing of first antenatal care visit and state and territory

Note: Due to differences in definitions and methods used for data collection, care should be taken in comparing across jurisdictions. See footnotes of Table 3.01.10 for details.

Source: Table D3.01.10. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Based on age-standardised data, in states and territories where numbers were large enough to support analysis (all except Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory), the largest absolute gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers attending antenatal care in the first trimester was for South Australia (a gap of 15.7 percentage points), followed by Queensland (13.3 percentage points), Western Australia (11.8 percentage points), Victoria (5.2 percentage points) and smallest for New South Wales (3.3 percentage points) (Table D3.01.10).

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended 5 or more antenatal visits ranged from 82% (in Western Australia) to 96% (in Tasmania) (Table D3.01.1).

Antenatal care by socioeconomic areas

In this section, data on the duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit refers to mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, while data on the number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy refers to mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation (see also Box 3.01.1).

Socioeconomic disadvantage in this measure is based on the 2016 Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas Index of Relative Socioeconomic Disadvantage (SEIFA IRSD), developed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. SEIFA IRSD scores for all geographical areas are divided into 5 quintiles, where areas belonging to the first quintile (lowest 20%) and the fifth quintile (highest 20%) referred to as the ‘most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas’ and the ‘least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas’, respectively.

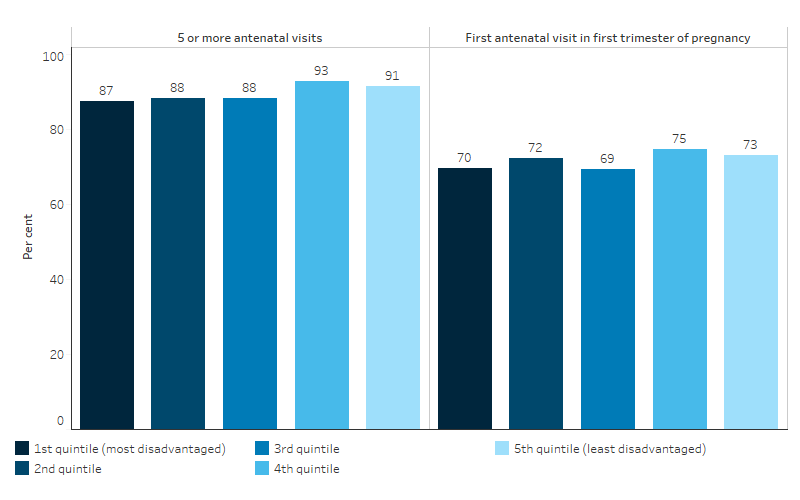

Compared with First Nations mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, First Nations mothers living in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas are more likely to attend their first antenatal visit in the first trimester of their pregnancy and are more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal visits during their pregnancy. In 2020:

- 73% of First Nations mothers living in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas attended antenatal care in the first trimester compared with 70% of those living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas.

- 91% of First Nations mothers living in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas had 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy, compared with 87% of First Nations mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (Table D3.01.24, Figure 3.01.5).

Figure 3.01.5: First Nations women who gave birth and attended 5 or more antenatal care visits in 2020, or had their first antenatal visit within the first trimester of pregnancy (<14 weeks), by socioeconomic area

Source: Table D3.01.24. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Comparing First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas, non-Indigenous mothers were more likely to attend first antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy and were more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal visits than First Nations mothers. After adjusting for differences in age structure between the two populations, for mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas in 2020:

- 77% of non-Indigenous mothers attended antenatal care in the first trimester, compared with 68% of First Nations mothers.

- 94% of non-Indigenous mothers had 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy, compared with 87% of First Nations mothers (Table D3.01.24).

Antenatal care and health conditions

In this section, data on the duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit refers to mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, while data on the number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy refers to mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation (see also Box 3.01.1).

In 2020, First Nations mothers with pre-existing diabetes (type 1/2), gestational diabetes, pre-existing hypertension or gestational hypertension were more likely to have their first antennal visit in the first trimester and 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy when compared with all First Nations mothers.

In 2020, among First Nations mothers with:

- pre-existing diabetes: 75% (254 of 339) had their first visit in the first trimester, and 90% (281 of 314) had 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy.

- gestational diabetes: 77% (1,611 of 2,105) attended their first antenatal visit in the first trimester, and 94% (1,966 of 2,082) had 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy.

- pre-existing hypertension: 81% (127 of 157) attended their first antenatal visit in the first trimester, and 93% (139 of 150) attended 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy.

- gestational hypertension: 75% (319 of 427) attended their first visit in the first trimester, and 88% (365 of 415) had 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy (Table D3.01.25).

In comparison, among all First Nations mothers, 71% (10,027 of 14,187) attended their first antenatal visit in the first trimester, and 88% (12,215 of 13,820) attended 5 or more visits (Table D3.01.1, D3.01.10).

In 2020, 43% of First Nations mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation smoked during pregnancy (Table D3.01.4). Of First Nations mothers who smoked both before and after 20 weeks of pregnancy, 40% had 10 or more antenatal visits, compared with 50% of those who did not smoke after 20 weeks of pregnancy (Table D3.01.26). See also measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy.

In 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who had their first antenatal visit within the first trimester of pregnancy was higher for mothers whose Body Mass Index (BMI) prior to pregnancy was classified as underweight or obese (74% each) than mothers with BMI classified as normal or overweight (71% each). A slightly higher proportion of First Nations mothers with a BMI classified as obese attended 5 or more antenatal visits during their pregnancy (92%) than mothers in other BMI categories (ranged from 88% to 89%) (Table D3.01.25).

Antenatal care and low birthweight and pre-term babies

In this section, data on the duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit refers to mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, while data on the number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy refers to mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation (see also Box 3.01.1).

In 2020, First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal care visit during the first trimester of pregnancy were less likely to have a baby of low birthweight (9.2% or 897 of 9,799 mothers), compared with those who either had their first visit at 20 weeks or more gestation or did not have any antenatal care during pregnancy (14.0% or 302 of 2,161 mothers) (Table D3.01.14).

Similarly, First Nations mothers who attended 5 or more antenatal visits during the course of their pregnancy were less likely to have a baby of low birthweight (7.5% or 904 of 12,023 mothers) than those who attended less than 5 visits or had no antenatal care during pregnancy (16.6% or 261 of 1,575 mothers) (Table D3.01.5).

First Nations mothers who attended their first antenatal care visit during their first trimester of pregnancy were less likely to have a pre-term baby (10.0% or 981 of 9,798 mothers), compared with those who had their first visit at 20 weeks or more gestation or did not have any antenatal visits (14.5% or 314 of 2,160 mothers) (Table D3.01.15).

Among First Nations mothers who gave birth at 32 or more weeks gestation, the rate of pre-term births among those who attended 5 or more antenatal visits (7.8% or 938 of 12,023 mothers) was less than one-half the rate of those who attended less than 5 visits or had no antenatal care during pregnancy (20.7% or 326 of 1,575 mothers) (Table D3.01.6).

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care organisations

The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander National Key Performance Indicators (nKPIs) data collection includes an item on antenatal care (PI13) provided by First Nations-specific primary health care organisations. In June 2023, of the 6,224 First Nations females who were regular clients of these organisations and gave birth in the previous 12 months, 42% attended their first antenatal visit before 14 weeks of pregnancy. The attendance rates varied with remoteness areas, were highest in Inner regional areas (57%) and lowest in Major cities (30%) (Table D3.01.22, Figure 3.01.6). Note that the denominator for the proportions includes those for whom gestational age at first antenatal visit was not recorded, and the level of completeness varies by remoteness areas.

The nKPI data include organisations funded to provide comprehensive primary health care (which includes child and maternal health care), as well as organisations receiving funding only for maternal and child health services. The latter are generally not primary health care organisations; instead, these are specific programs or services embedded within hospitals, health services, or primary health networks.

At 30 June 2023:

- 16 organisations received funding for maternal and child health care services only. In these organisations, 58% of the 1,161 First Nations female regular clients who gave birth in the previous 12 months received antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy.

- 186 organisations received funding for comprehensive primary health care – 38% of the 5,063 First Nations female regular clients of these organisations who gave birth in the previous 12 months received antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy (AIHW analysis of nKPI data).

Figure 3.01.6: First Nations regular clients of First Nations-specific primary health care organisations, female clients, by duration of pregnancy at first antenatal visit and remoteness, June 2023

Source: Table D3.01.22. AIHW analysis of the National Key Performance Indicators for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Primary Health Care collection.

Changes over time

In this section, data on the duration of pregnancy at first antenatal care visit refers to mothers who gave birth at 20 weeks or more gestation, while data on the number of antenatal care visits during pregnancy refers to mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation (see also Box 3.01.1).

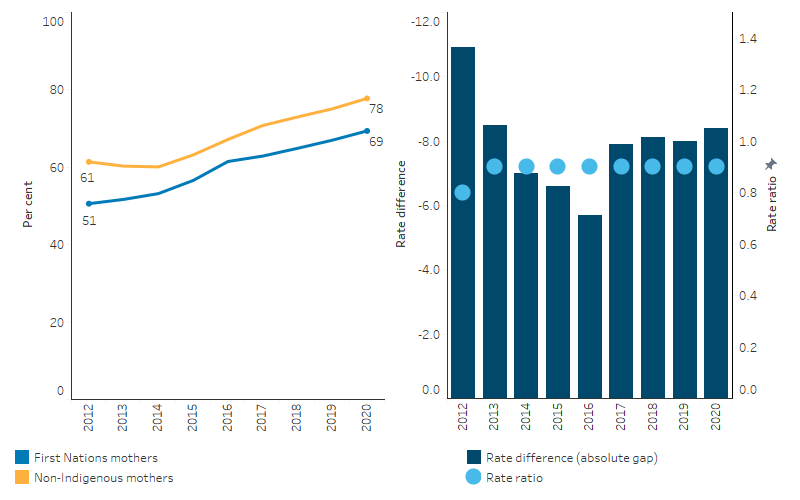

Between 2012 and 2020, the proportion of First Nations mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy increased from 50% to 71% (Table D3.01.21).

Based on age-standardised rates, the proportion of mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester of their pregnancy (before 14 weeks gestation) increased by 41% for First Nations mothers and by 33% for non-Indigenous mothers.

Over the first 5 years of this period (2012 to 2016), the absolute gap in the age-standardised proportion of First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers attending antenatal care in the first trimester declined (from a difference of 10.9 percentage points to a difference of 5.7). However, in the 4 years following, the absolute gap increased to a difference of 8.4 percentage points in 2020. The relative difference in rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous mothers was largely consistent over the period, with the age-standardised proportion of First Nations people attending antenatal care in the first trimester averaging around 0.9 times as high for First Nations people as for non-Indigenous Australians between 2012 and 2020 (Table D3.01.21, Figure 3.01.7).

The most recent year of data presented in this measure, for 2020, overlaps with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Analysis of Medicare claims data (for the total population) shows that while there was a reduction in the number of face-to-face services between 2019 and 2020, this was largely compensated for by telehealth services (see Box 3.01.2).

Figure 3.01.7: Age-standardised proportion of women who gave birth and attended at least one antenatal care visit during the first trimester (<14 weeks), by Indigenous status, 2012 to 2020

Source: Table D3.01.21. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Research and evaluation findings

The literature suggests that improved access to, and use of, antenatal care services improve outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies. Studies have shown an association between inadequate antenatal care and increased risk of stillbirths, perinatal deaths, retardation of fetal growth, low birthweight and pre-term births (AIHW 2014; Taylor et al. 2013).

Based on a multivariate analysis of singleton births for the period 2018–2020, attending antenatal care within the first trimester was associated with a lower rate of low birthweight among First Nations babies, after adjusting for other maternal health characteristics. When accounting for the rate of antenatal care attendance by mothers of First Nations babies, an estimated 4.6% of low birthweight in First Nations babies was attributable to lack of antenatal care (attending after the first trimester or did not attend any antenatal care) (Table D1.01.8). If the antenatal attendance rates among mothers of First Nations babies were the same level as mothers of non-Indigenous babies, the proportion of low birthweight in First Nations babies could be reduced by 1.7% (see measure 1.01 Birthweight) (Table D1.01.8). See also the HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies for additional statistical analysis on birthweight. The article presents more detailed statistical analysis on low birthweight including trend analysis of gestational age (pre-term, early-term, full-term births), birthweight and key contributing factors such as maternal health, smoking during pregnancy and antenatal care attendance. It also provides analysis of the level of improvement required in smoking rates to meet the birthweight target in the National Agreement.

Maternal Health and birth outcomes

Since colonisation, the lifestyle of First Nations Australians has undergone a rapid transition towards Western lifestyles over a relatively short period of time, and the prevalence of overweight/obesity has become high. In a retrospective cohort study using data linkage of all singleton births in Western Australia (using the Western Australian Data Linkage System), obesity had a stronger association with gestational diabetes in First Nations mothers compared to non-Indigenous mothers. The international literature has shown that gestational diabetes mellitus is the most common complication in pregnancy, and increases the risk of fetal overgrowth, respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal hypoglycaemia, pre-term birth, hyperbilirubinemia and polyhydramnios. Moreover, gestational diabetes has negative long-term implications for both the child and mother. In Australia, gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence is consistently higher among First Nations women. First Nations mothers were also more likely to: be younger, have higher parity, have smoked during pregnancy and live in Remote or Very remote areas. The likelihood of gestational hypertension, eclampsia/pre-eclampsia and adverse obstetric history events (such as previous events of: Large for Gestational Age (LGA), macrosomia, stillbirth and birth defects) were higher in First Nations mothers than in non-Indigenous mothers. Maternal obesity significantly increases the risk of pregnancy complications among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2023).

In a related study in Western Australia by the same authors, analysis was conducted on the impact of diabetes in pregnancy on trends for births that were LGA. The study found that between 1998 and 2015 the age-standardised rates of pre-gestational diabetes among First Nations mothers rose from 4.3% in 1998 to 5.4% in 2015 but remained below 1% among non-Indigenous women. Over the same period, rates of gestational diabetes rose from 6.7% to 11.5% for First Nations women, and from 3.5% to 10.2% for non-Indigenous women. Analysis highlighted that diabetes in pregnancy substantially contributed to increasing trends in LGA among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2022).

A retrospective cohort analysis of the Northern Territory Perinatal Data Collection from 1987 to 2016 found that rates of pre-existing diabetes and gestational diabetes among First Nations mothers increased over the period, as did rates of LGA and high birthweight. Modelling found that hyperglycaemia in pregnancy had grown substantially in the Northern Territory over the 3 decades and this was largely responsible for the growing rates of LGA births among First Nations women (Hare et al. 2020).

Women with pre-existing type 2 diabetes (T2D) in pregnancy have a higher risk of miscarriage, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, caesarean section and longer stays in hospital, compared with mothers with gestational diabetes and mothers without hyperglycaemia in pregnancy. Babies of mothers with pre-existing T2D have higher rates of stillbirth, high birthweight, low Apgar scores, high-level resuscitation, special care nursery/neonatal intensive care unit admissions and longer stays in hospital compared with babies of mothers with gestational diabetes or babies of mothers without hyperglycaemia in pregnancy (Wood 2022).

The prevalence of T2D is higher for First Nations women than non-Indigenous women across all ages, but particularly for younger age groups. Accordingly, First Nations women are more likely to have T2D in pregnancy (ABS 2019). More broadly, higher rates of T2D/pre-existing diabetes and gestational diabetes among First Nations mothers contribute to poorer pregnancy outcomes and long-term consequences for mothers and children. This can be seen among indigenous women in countries with similar histories of colonisation such as Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States (Voaklander et al. 2020). Research suggests that prevention or delay of onset of T2D in younger women is vital to improving pregnancy outcomes (Maple-Brown et al. 2019). The burden of diabetes facing pregnant indigenous women in countries with similar colonisation histories is amplified by the effect of social determinants, which makes it all the more important that services providing diabetes care for indigenous women are culturally safe (Maple-Brown & Hampton 2020).

Continuity of care, cultural safety and accessibility

A recent study found that First Nations women receiving continuity care led by ACCHSs were more likely to access early antenatal care and have 5 or more antenatal visits, with significantly reduced pre-term births, neonatal nursery admissions, planned caesareans, and epidural pain relief, and increased exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital (Kildea et al. 2021).

An integrative literature review highlighted a lack of continuity in the antenatal, peri- and post-natal periods for First Nations families compared with non-Indigenous families. Access to timely, effective and appropriate maternal and child healthcare can contribute to reducing health disparities. However, accessing mainstream healthcare services often results in high levels of fear and anxiety for First Nations women, resulting in low attendance at subsequent appointments, due to inefficient communication, poor service coordination and a lack of continuity of care (Sivertsen et al. 2020). The authors followed up with a study to explore mainstream health workers’ perspectives of what contributes to positive care experiences for First Nations women and their infants. Three key themes emerged: ‘the system takes priority’, ‘culture is not central in approaches to care’, and ‘we’ve got to be allowed to do it in a different way’. The study found that continuity of care for First Nations families in the mainstream healthcare system was delivered inconsistently and often in culturally unsafe ways (Sivertsen et al. 2022).

A longitudinal follow-up study conducted in 2019–20, which interviewed 14 non-Indigenous midwifery students or recent graduates from 2012–14, found that exposure to First Nations content and community placement opportunities during training had a lasting impact on participants midwifery practice. Most former students reported feeling better prepared to provide culturally safe care, build respectful relationships and advocate for improved services for First Nations women (Thackrah et al. 2020).

Another integrative literature review explored enabling factors and barriers that influenced First Nations families’ engagement with maternal and child health services. Enabling factors included service models or interventions that are: timely and appropriate; effective, integrated, community-based and flexible in their approach; holistic; culturally strong; and facilitative of early identification of risk factors and the need for further assessment, intervention, referral, and support. Barriers that influenced First Nations families’ engagement with maternal and child health services were: inefficient communication resulting in lack of understanding between the client and the provider; cultural differences between the client and the provider; poor continuity of care between services; lack of flexibility in approach/access to services; and a model of care that does not recognise the importance of the social determinants of health and wellbeing (Austin et al. 2022).

In 2013, a multi-agency partnership between 2 ACCHSs and a Brisbane tertiary maternity hospital co-designed the Birthing in Our Community service (BiOC), which aimed to improve health outcomes and reduce pre-term birth (Kildea et al. 2021). An analysis of the clinical effectiveness of the BiOC service for women who gave birth to a First Nations baby at this hospital during January 2013–June 2019 found that women who received the BiOC service were less likely than women receiving standard care to give birth to a pre-term infant. These women were also more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal visits and to exclusively breastfeed on discharge from hospital. The results suggest that improving health outcomes of mothers and babies and reducing pre-term birth is possible when First Nations women are targeted early in their pregnancies for antenatal care, through:

- providing culturally safe continuity of care

- providing a holistic service

- providing a service with high levels of community investment (collective understanding and valuing of a program), ownership (the program is ‘ours’), and activation (high-level of community participation)

- health service leadership across partner organisations

- strengthening the First Nations workforce.

A study by Brown et al. (2015) investigated experiences of antenatal care in South Australia among 344 women who gave birth to a First Nations baby between July 2011 and June 2013 (Brown et al. 2015). Women who received antenatal care that was consistent with their culture and needs were more likely to rate the services they received as ‘very good’ compared with women attending mainstream services. Only 36% of women receiving mainstream public care described their antenatal care as ‘very good’ compared with 65% of women attending an Aboriginal Health Service, 63% of women receiving care from a metropolitan Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (AFBP), 54% of women attending a regional AFBP service, and 53% of women receiving care from a midwifery group practice.

A study by Brown et al. (2016) drew on the same data to investigate women’s access to antenatal care by geography. Mothers of First Nations babies who attended regional AFBP services were more likely to access antenatal care in the first trimester and markedly more likely to attend 5 visits during pregnancy than those receiving mainstream regional services. Women receiving these services in urban areas were also more likely to attend at least 5 visits compared with those attending mainstream regional services (Brown et al. 2016a).

Many factors have been identified that influence a First Nations woman’s engagement with, and early presentation for, antenatal care including the availability of culturally appropriate services, the frequency (or absence) of local clinics, transport, and educational, socioeconomic and financial issues (Arnold et al. 2009; de Costa & Wenitong 2009). A study of the geographic access for First Nations women of child bearing age (15–44 years) to maternal health services found that poorer access to First Nations-specific primary health care services with maternal/antenatal services was associated with higher rates of smoking and low birthweight (AIHW 2017).

Program evaluations

A study to identify evidence-practice gaps and strategies for improvement in First Nations maternal health care was conducted by researchers from various Australian institutions, including Monash University and the University of Sydney. The objective of this research was to engage stakeholders in a theory-informed process using aggregated continuous quality improvement (CQI) data to pinpoint priority evidence-practice gaps in First Nations maternal health care, identify barriers and enablers to high-quality care, and strategise solutions to address these priorities. The study utilised de-identified CQI data from 91 health services between 2007 and 2014, encompassing 4,402 client records, and involved 172 stakeholders from diverse professions and organisations. Key findings highlighted 4 priority areas related to non-communicable diseases (NCDs): smoking, alcohol, psychosocial wellbeing, and nutrition. Barriers and enablers to high quality care encompassed workforce support, professional development, teamwork, woman-centred care, decision support, equipment, and community engagement. To address these, stakeholders proposed strategies such as upskilling staff, advocating for healthy food availability, partnering with communities on health promotion, and establishing clear referral pathways. The study highlights the importance of addressing evidence-practice gaps related to NCD risk factors and social determinants of health in maternal care for First Nations populations, emphasising both healthcare-focused initiatives and broader community and health sector involvement (Gibson-Helm et al. 2018).

A suite of evaluations has been published across Australia on programs to improve the delivery of antenatal services to First Nations women with the intent of improving birth outcomes. The Clinical Practice Guidelines—Pregnancy Care (2020 edition), outlines evidence of successful models of care from these evaluations specifically tailored for First Nations women, such as the Aboriginal Maternity Group Practice Program (AMGPP); Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (AFBP); and the Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Service (AMIHS) (Bertilone & McEvoy 2015; Bertilone et al. 2017; Department of Health 2020; Middleton et al. 2017; Murphy & Best 2012). These programs highlight the importance of culturally appropriate and safe care as well as continuity of care, collaboration between midwives and First Nations health workers, and the role of family members such as grandmothers in positively influencing maternal healthy lifestyle behaviours during pregnancy and attendance at care sessions. These practices can have quantifiable improvements in antenatal care attendance, pre-term births, birth outcomes, perinatal mortality, and breastfeeding (Department of Health 2020).

The guidelines also mention that while these programs have been identified as beneficial, not all First Nations women have access to these types of programs and many still rely on mainstream services, such as GPs and public hospital clinics (Clarke & Boyle 2014; Corcoran et al. 2017). However, mainstream maternity services are often under-resourced and lack systems to provide culturally responsive care that meets the needs of women experiencing multiple social and health issues during pregnancy. Hence, it is important that mainstream services embed cultural competency into continuous quality improvement. Participation in a continuous quality improvement initiative by primary health care centres in First Nations communities is associated with greater provision of pregnancy care aimed at addressing lifestyle related risk factors (Gibson-Helm et al. 2016).

A range of programs have been implemented around the country to improve the delivery of antenatal services to First Nations women. Evaluations have shown their success in improving uptake of care earlier in pregnancies, for the duration of the pregnancy and often postnatally, which allows other opportunistic health-care interventions, such as family planning, cervical screening and improving breastfeeding rates (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Examples of evaluated programs include:

- Midwifery group practice: There were improvements in antenatal care (fewer women had no antenatal care and more had greater than 5 visits), antenatal screening and smoking cessation advice and a reduction in fetal distress in labour. Cost-effective improvements were made to the acceptability, quality and outcomes of maternity care. Evidence-informed redesign of maternity services and delivery of care has improved clinical effectiveness and quality for women. However, more work is needed to address substandard care provided for infants and their parents (Barclay et al. 2014).

- Midwifery continuity of care: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies undertaken in Australia and Canada found that overall, the experience of midwifery services was valuable for indigenous women. The most positive experiences for women were with services that provided continuity of care, had strong community links and were controlled by indigenous communities. However, there are barriers preventing the provision of intrapartum midwifery care in remote areas (Corcoran et al. 2017).

- Aboriginal Maternity Group Practice Program (AMGPP): The AMGPP employed First Nations grandmothers, First Nations Health Officers and midwives working in partnership with existing antenatal services to provide care for pregnant First Nations women residing in south metropolitan Perth. Babies born to women in the program were significantly less likely to be born pre-term; to require resuscitation at birth; or to have a hospital length of stay greater than 5 days. Analysis of qualitative data from surveys and interviews found that the model had a positive impact on the level of culturally appropriate care provided by other health service staff, particularly in hospitals. Participation in the AMGPP in south metropolitan Perth was associated with significantly improved neonatal health outcomes (Bertilone & McEvoy 2015).

- Aboriginal Family Birthing Program (AFBP): The AFBP provides culturally competent antenatal, intrapartum and early postnatal care for First Nations families in some parts of South Australia, with women cared for by an Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Care worker and a midwife in partnership. Compared with women attending mainstream public antenatal care, women attending metropolitan and regional AFBP services were more likely to report positive experiences of pregnancy care. The AFBP reaches out to women with the greatest need, providing culturally appropriate, effective care through partnerships (Middleton et al. 2017).

- Aboriginal Maternal and Infant Health Service (AMIHS): the AMIHS was established in New South Wales to improve the health of First Nations women during pregnancy and decrease perinatal morbidity and mortality for First Nations babies (Murphy & Best 2012). The AMIHS is delivered through a continuity-of-care model, where midwives and First Nations Health Workers collaborate to provide a high-quality maternity service that is culturally sensitive, women-centred, based on primary health-care principles and provided in partnership with First Nations people (although not community controlled and led). An evaluation of the AMIHS found the proportion of women who attended their first antenatal visit before 20 weeks increased; the rate of low birthweight babies decreased; the proportion of pre-term births decreased; perinatal mortality decreased; and breastfeeding rates improved. While these programs have been identified as beneficial, not all First Nations women have access to these types of programs and many still rely on mainstream services such as GPs and public hospital clinics (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Hence, it is important that mainstream services embed cultural competence into continuous quality improvement.

- An evaluation of the Murri Antenatal Clinic (based in an Australian hospital) found that the majority of women who attended the clinic felt understood and respected by the staff, which included a First Nations midwife and First Nations Liaison Officers. The clients were statistically less likely to experience perineal trauma, undergo an elective caesarean operation or have a baby admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit. However, the limited clinic opening hours were insufficient to meet demand, which presented a barrier to attendance for women (Kildea et al. 2012).

Panaretto et al. (2005) evaluated the effect of a community‐based, collaborative, shared antenatal care intervention (the Mums and Babies program) for First Nations women at the Townsville Aboriginal and Islander Health Service (community-controlled). This program was based on continuity of care, cultural currency and a family‐friendly environment. Women in the intervention group had significantly more antenatal care visits, and improved timeliness of the first visit. There were significantly fewer pre-term births in the intervention group. This study showed that integrated services delivered in a culturally aware and safe environment increased access to antenatal care in the First Nations community. It is possible for this model to be adapted to other urban centres that have significant First Nations populations, community‐controlled health services and with multiple providers of antenatal care (Panaretto et al. 2005).

A follow up study also showed that the Townsville Mums and Babies program sustained these improvements, and later improved perinatal outcomes for participants, with the reduction in pre-term births later translating into reduced perinatal mortality. Among Townsville-based participants, there was also an increase in mean birthweight, compared with the control group (prior to the start of the program) (Panaretto et al. 2007).

An evaluation of the Malabar service – a community‐based culturally appropriate service that addressed the antenatal care needs of First Nations mothers – found that the continuity of care was the most valued aspect of the service. The midwives and First Nations health workers were seen as friendly, supportive, engaged, and approachable. The development of trust was a recurring theme during the evaluation (Homer et al. 2012). Malabar was considered to provide more than just a maternity service, with women stating that it also helped to establish social networks and play groups. A more recent evaluation of the Malabar service over 2007 to 2014 found a 25% reduction in the rate of smoking after 20 weeks gestation, but similar rates of pre-term birth, breastfeeding at discharge and a higher rate of low birthweight babies, compared with mainstream services (Hartz et al. 2019). However, Malabar outcomes were better than state and national outcomes.

In contrast, an audit in Western Australia that explored the usage, frequency, and characteristics of services in publicly funded antenatal services for First Nations women in metropolitan, rural and remote regions identified significant gaps. The audit found that around three-quarters of the antenatal services used by First Nations women had not achieved a model of service delivery consistent with the principles of culturally responsive care (Reibel & Walker 2010).

Antenatal care also provides the opportunity to affect other outcomes broader than pregnancy and birth. The ANFPP is an evidence-based nurse home visiting program for mothers who are pregnant with a First Nations baby. The implementation of the ANFPP in Central Australia, delivered by a large ACCHS, was evaluated for its effect on child protection outcomes among children in the program (Segal et al. 2018). This evaluation found that the program may have reduced child protection system involvement, especially among younger or first-time mothers, and reduced the incidence of out-of-home care placements among children in the program. While the ANFPP has an antenatal focus, participants remain in the program until their children are 2 years old. Therefore, the outcomes reported in this evaluation are not solely attributable to the antenatal care stage of the program.

More recently, the evaluation of the ANFPP found that the program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy, growth, and empowerment. Three main themes were generated: 1) sustaining connections and relationships; 2) developing self-belief and personal skills; and 3) achieving transformation and growth. When the program facilitates the development of culturally safe relationships with staff and peers, it enables behaviour change, skill development, personal goal setting and achievement, leading to self-efficacy. Located within a community-controlled health service, the program can foster cultural connection, peer support and access to health and social services; all contributing to self-efficacy (Massi et al. 2023).

Mental health screening during pregnancy

Internationally, a review found that although indigenous women are exposed to high rates of risk factors for perinatal mental health problems, the magnitude of their risk is not known. Indigenous women are at increased risk of mental health problems during the perinatal period, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance misuse. When all types of mental health problems were considered, indigenous status was associated with 62% higher odds of experiencing such a problem than non-indigenous women. Indigenous mothers with mental health problems are younger and suffer from more severe illness than non-indigenous mothers (Owais et al. 2020).

Maternal mental health disorders have been associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as low birthweight and pre-term birth in the literature. A retrospective cohort study using data linkage (N=38,592) using all Western Australian singleton First Nations births (1990–2015) found around 19% of births were to women with at least one mental health disorder reported in the 5 years preceding birth. The study found that compared with not having a mental health disorder, having a disorder in the 5 years before giving birth was associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as pre-term birth (risk ratio 1.48) and low birthweight (risk ratio 1.81), after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and pre-existing medical conditions. The size of the associations did not vary considerably when examined by type of mental health disorder. The authors argued that prevention and early identification of First Nations women with mental health disorders using culturally validated tools, provision of holistic antenatal care, and provision of culturally safe mental health treatment and support, may improve adverse perinatal and later life outcomes (Adane et al. 2023).

The Kimberley Mum’s Mood Scale (KMMS), developed in collaboration with First Nations women in northwest Australia, has emerged as a significant innovation in perinatal mental health screening practices for these women. Validated in 2016, the KMMS was found to be acceptable and accurate in identifying depression and/or anxiety. Carlin (2023) implemented the KMMS across primary health care services in the Kimberley region, aiming to evaluate its effectiveness and transferability. The results were promising, with significant increases in perinatal mental health screening rates across Kimberley Aboriginal community-controlled health services and a notable shift towards the exclusive use of the KMMS. The research underscored the importance of screening for protective factors, such as positive relationships with family members, when assessing the mental health of First Nations women. These protective factors, which emerged during the co-design process, were identified as critical to the tool's acceptability and were associated with lower levels of anxiety or depression. These findings challenge the deficit discourse often associated with Aboriginality and promotes a decolonised health paradigm that views Aboriginality and First Nations families from an empowerment standpoint. The KMMS is now embedded in the Kimberley practice, available for other regions to use, and represents a significant investment with the potential to improve health outcomes (Carlin 2023).

Despite high rates of perinatal depression and anxiety, little is known about how First Nations women in Australia experience these disorders and the acceptability of current clinical screening tools. Yarning as a methodology was used to guide interviews with 15 First Nations women in the Pilbara who had received maternal and child health care within the last 3 years. Data were analysed thematically, the results revealing that this cohort of participants shared similar experiences of stress and hardship during the perinatal period. Participants valued the KMMS for its narrative-based approach to screening that explored the individual's risk and protective factors. Seven of the 15 women spoke about their experience with, or a close family member’s experience with, perinatal depression and/or anxiety. A further 6 women identified extreme and multiple stressors during their own perinatal period (violence, homelessness, drug and alcohol use, child protection intervention, traumatic birth outcomes, primary health problems) but did not talk about depression or anxiety. They talked about things being ‘hard’ or ‘stressful’. Several participants suggested that family do not always have the capacity to ‘help take the load off’, particularly families that are struggling with the effects of intergenerational trauma and/or intergenerational alcohol misuse. Most participants stated that outside of the clinical environment, conversations about their mental health and wellbeing were not occurring, even for women who had close and supportive intimate and familial relations, which highlights the critical and unique role that health care professionals have in engaging and supporting First Nations women’s mental health during the perinatal period. The women in this study valued clinical screening tools that allow for exploration of these and other significant areas of their life in a way that was gentle and provided them an opportunity to reflect on their strengths and protective factors. Current mainstream approaches to psychosocial screening do not reflect these values (Carlin et al. 2019).

Implications

A key component of improving pregnancy outcomes is early and ongoing engagement in antenatal care, which is facilitated by the provision of culturally appropriate and evidence-based care relevant to the local community (Clarke & Boyle 2014). While there have been improvements in antenatal care attendance, there is a need to engage First Nations mothers earlier in their pregnancy.

Strategies addressing potentially modifiable risk factors for pre-term birth, low birthweight and small for gestational age babies should be an important focus of antenatal care delivery. The HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies presents more detailed statistical analysis on low birthweight including trend analysis of gestational age (pre-term, early-term, full-term births), birthweight and key contributing factors such as maternal health, smoking during pregnancy and antenatal care attendance.

Being born with a low birthweight may have consequences later in life. The fetal origins hypothesis associated with David J. Barker posits that chronic, degenerative conditions of adult health, such as type 2 diabetes and heart disease, may be triggered by circumstances in utero (Almond & Currie 2011). An analysis of deaths in a cohort of young adults born in a remote First Nations community between 1956 and 1985 found that low birthweight was associated with higher death rates, and the effect was particularly prominent for deaths that occurred at under 41 years of age and with deaths from respiratory conditions or sepsis and unusual causes (Hoy & Nicol 2019).

International and Australian research has also shown the increased risks of adverse outcomes of obesity, pre-existing diabetes and diabetes in pregnancy for First Nations women and their children including LGA and high birthweight, with impact into adulthood (Ahmed et al. 2023; Ahmed et al. 2022; Duong et al. 2015; Hare et al. 2020; Wicklow et al. 2018; Wood 2022). Epigenetic and intergenerational factors (including trauma) are thought to contribute to increasing rates of obesity among First Nations populations and further research is needed (Schafte & Bruna 2023). Across nations with similar histories of colonisation, the burden of diabetes is amplified by the effect of social determinants which makes it all the more important that services providing diabetes care for indigenous women are culturally safe (Maple-Brown & Hampton 2020). First Nations women receiving continuity of care compared with standard care were more likely to access early antenatal care and have 5 or more antenatal visits, more likely to give birth successfully to a healthy baby, with significantly reduced pre-term births, neonatal nursery admissions, planned caesareans, and epidural pain relief, and had increased rates of exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital (Kildea et al. 2019; Kildea et al. 2021). Culturally safe and comprehensive antenatal care supports women to increase their health literacy and self-efficacy, improving maternal and baby health outcomes at birth and throughout their life course (Massi et al. 2023).

Many First Nations women live in urban or inner regional areas and receive health care through mainstream services, and it is important for all practitioners to be aware of how to optimise care to First Nations women (Clarke & Boyle 2014). Some First Nations women may prefer to go to an Aboriginal Health Service or ACCHSs, but there may also be a preference for privacy and a reluctance to use a service where they are known to employees, especially early in the pregnancy when having the time to tell family members before other people find out is important (Reibel & Morrison 2014; Reibel et al. 2015).

The features that have been identified for quality primary maternity services in Australia include high-quality care that is enabled by evidence-based practice, coordinated according to the woman’s clinical needs and preferences, based on collaborative multidisciplinary approaches, woman-centred, culturally appropriate and accessible at the local level (AHMAC 2012).

Reviews of the literature have identified the following key success factors in First Nations maternal health programs to complement the features detailed above:

- a safe and welcoming environment

- outreach and home visiting

- flexibility in service delivery and appointment times

- access to transport

- continuity of care and carer integration with other services (for example, ACCHSs or hospital)

- a focus on communication, relationship building and trust

- involvement of women in decision-making

- respect for First Nations culture

- respect for privacy, dignity, and confidentiality

- family involvement and childcare;

- appropriately trained workforce;

- First Nations staff and female staff;

- informed consent and right of refusal;

- tools to measure cultural competency (AHMAC 2012; Bertilone & McEvoy 2015; Dudgeon et al. 2010; Herceg 2005; Kildea et al. 2012; Kildea & Van Wagner 2013; Murphy & Best 2012; Reibel & Walker 2010; Wilson 2009).

The Australian Government has allocated funding from 2021–22 to 2024–25 to extend the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) at 13 existing locations and introduce it to 2 new areas in Western Australia. The ANFPP, tailored for First Nations communities, offers home visits by nurses to women expecting a First Nations child, supporting them from pregnancy until the child is 2 years old. It also funds several initiatives to enhance antenatal care and health behaviours for First Nations women during pregnancy, including: Baby coming you ready; National Preterm Birth Prevention Program; and the Women-centred care strategy. The ANFPP has been operating in Australia since 2009. The program has been adapted to best support First Nations communities in Australia and includes the role of a Family Partnership Worker, who works alongside the nurse, bringing an understanding of the local community and increased cultural safety to program delivery. ANFPP staff are guided by client-centred principles that enable each woman in the program to make healthy choices for herself and her family. Through empowerment and education, ANFPP mothers develop a strong foundation for parenting which builds protective factors resulting in better health, safety, wellbeing and development outcomes for both women and children.

Enhanced primary care services and continued improvement in, and access to, culturally appropriate antenatal care have the capacity to support improvements in the health of the mother and baby. This highlights the important role ACCHSs have in leading culturally safe and responsive health care within their communities (Panaretto et al. 2014). ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. The Australian Government committed to building a strong and sustainable First Nations community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people across the country under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement. Further work to ensure mainstream services can provide culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations people is also critically important and relates to Priority Reform Three of the National Agreement. These 2 dimensions of health care for First Nations people have been emphasised in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course.

The Health Plan, released in December 2021, is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap Priority Reforms and health targets. Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure a strong start to life. Comprehensive, wrap-around, community-led Birthing on Country services have the potential to support healthy pregnancies by offering an integrated, holistic and culturally safe model of care (Department of Health 2021a).

Research has shown that Birthing on Country (BoC) models of care, which offer culturally safe, continuous midwifery care for First Nations women, improve birth outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies (such as improving frequency of antenatal care visits and reducing the likelihood of pre-term birth). The Australian Government is actively promoting the BoC model, especially in rural and remote areas where birthing outcomes can be challenging. To support this, the Australian Government has committed $32.2 million over 4 years (2021–22 to 2024–25) under the Healthy Mums, Healthy Bubs initiative to enhance the maternity health workforce and BoC practices. Additional funding ($22.5 million) has also been allocated over 3 financial years (2022–23 to 2024–25) for the establishment of a BoC Centre of Excellence at Waminda in Nowra, New South Wales. The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) also funded The BoC: RISE SAFELY study with $5 million, which will establish exemplar BoC services in 3 rural, remote and very remote settings. The study is First Nations led, co-designed and staffed. More broadly, the Department of Health and Aged Care is partnering with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to develop a maternal and child health model of care to enable First Nations mothers and families to access consistent, culturally safe and effective care (NIAA 2023).

As part of the National Agreement, the health sector was identified as one of 4 initial sectors for a joint national strengthening effort and the development of a 3-year Sector Strengthening Plan. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) was developed in 2021, to acknowledge and respond to the scope of key challenges for the sector, providing 17 transformative sector strengthening actions. Developed through strong consultation across the First Nations community-controlled health sector and other the First Nations health organisations, the Health-SSP will be used to prioritise, partner and negotiate beneficial sector-strengthening strategies.

The Connected Beginnings Program, funded by the Australian Government, aims to support the early life development of First Nations children. The program focuses on enhancing First Nations families' engagement with health, early childhood education, and maternal services. It integrates local support services, allowing families to access culturally appropriate resources, with the goal of ensuring that children are safe, healthy, and prepared to thrive at school by the age of 5. The program is community-owned and led, emphasising collaboration with First Nations communities across various sites in Australia.

Australian governments are investing in a range of other initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. These are provided in the Policies and strategies section.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

-

ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2019. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018-19. Canberra: ABS.

-

ABS & AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2008. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2008. Canberra: ABS & AIHW.

-

ACOG (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists) 2023. How your fetus grows during pregnancy. Viewed 30 October 2023.

-

Adane A, Shepherd C, Walker R, Bailey H, Galbally M & Marriott R 2023. Perinatal outcomes of Aboriginal women with mental health disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57.

-

AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2012. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. (ed., Department of Health and Ageing). Canberra: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

-

Ahmed M, Bailey H, Pereira G, White S, Hare M, Wong K et al. 2023. Overweight/obesity and other predictors of gestational diabetes among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in Western Australia. Preventive Medicine Reports 36:102444.

-

Ahmed M, Bailey H, Pereira G, White S, Wong K & Shepherd C 2022. Trends and burden of diabetes in pregnancy among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal mothers in Western Australia, 1998–2015. BMC Public Health 22:263.

-

AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Headline indicators for children's health, development and wellbeing 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2014. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2017. Spatial variation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's access to 4 types of maternal health services. Canberra: AIHW.

-

AIHW 2021. Antenatal care during COVID–19, 2020. Canberra: AIHW. Viewed 31 October 2023.

-

AIHW 2022. Determinants of health for Indigenous Australians. Canberra: AIHW.

-

Almond D & Currie J 2011. Killing me softly: The fetal origins hypothesis. Journal of economic perspectives 25:153-72.

-

Arabena K, Howell-Muers S, Ritte R, Munro-Harrison E & Onemda VicHealth Koori Health Unit 2015. Making a World of Difference - The First 1,000 Days Scientific Symposium report Melbourne.

-

Arnold JL, De Costa CM & Howat PW 2009. Timing of transfer for pregnant women from Queensland Cape York communities to Cairns for birthing. The Medical Journal of Australia 190:594-6.

-

Austin C, Hills D & Cruickshank M 2022. Models and Interventions to Promote and Support Engagement of First Nations Women with Maternal and Child Health Services: An Integrative Literature Review. Children 9, no. 5:636.

-

Austin M, Colton J, Priest S, Reilly N & Hadzi-Pavlovic D 2013. The antenatal risk questionnaire (ANRQ): acceptability and use for psychosocial risk assessment in the maternity setting. Women Birth 26:17-25.

-

Barclay L, Kruske S, Bar-Zeev S, Steenkamp M, Josif C, Narjic CW et al. 2014. Improving Aboriginal maternal and infant health services in the ‘Top End’ of Australia; synthesis of the findings of a health services research program aimed at engaging stakeholders, developing research capacity and embedding change. BMC health services research 14:241.

-