Key messages

- The Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) registers and regulates Indigenous corporations according to the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act) and provides support and advice to help them manage their affairs effectively.

- The data show that the majority of Indigenous primary health care providers are demonstrating sound governance arrangements, including planning processes and having a governing committee/board in place.

- In 2021–22, 674 Indigenous corporations that identified as having principal activities of health and community services were incorporated under the CATSI Act and were registered with ORIC. Around 64% (432) of these corporations complied with their obligations to submit annual reports to ORIC.

- In 2021–22,162 of the 211 (77%) Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported having a governing committee/board; 91 (56%) had a committee/board who were all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people.

- Of the 162 Indigenous primary health care organisations in 2021–22, 79 (49%) of them had governing committee/board members who had received training related to governance issues, 91 (56%) had a committee/board who were all Indigenous Australians, and 69 (43%) had a board that included at least one independent (skill-based) member.

- In 2017–18, 77 of the 79 (97%) Commonwealth-funded organisations providing substance-use services for Indigenous Australians reported having a governing committee/board; 47 (61%) of these had a committee/board who were all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people.

- Competent governance also includes participation in planning processes and engagement with community members. In 2017–18, 195 of the 198 (99%) Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported having accessible and appropriate client/community feedback mechanisms in place.

- In 2017–18, 97% of Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations participated in organisational planning processes.

- Aspects of good practice by governments to support the governance of Indigenous organisations include long-term contracting, good contract management, risk sharing, working with Indigenous Australians in decision-making, research and evaluation, and simplified data collection, monitoring and information sharing.

Why is it important?

‘Governance’ refers to the evolving processes, relationships, institutions and structures by which a group of people, community or society organise themselves collectively to achieve things that matter to them. Governance enables the representation of the welfare, rights and interests of constituents, the administration and delivery of programs and services, the management of resources, and negotiation with governments and other groups (Hawkes 2001; Hewitt de Alcántara 1998; Westbury 2002). Governance occurs at the community, local, regional and national level. The manner in which governance functions are performed has a direct effect on the wellbeing of individuals and communities.

Competent governance in the context of Indigenous primary health care services ensures the services are effectively and efficiently managed, and that the cultural, social and health needs of Indigenous communities are taken into account. This measure explores the role of competent governance of Indigenous primary health care services in the delivery of care to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Within governance, appropriate consultation and engagement with Indigenous communities in decision-making processes play a vital role in the delivery of primary health care for Indigenous Australians. Community control of health services allows Indigenous Australian communities to determine their own priorities, protocols and procedures. The care these services provide will also reflect the values and principles of the community they serve. It can also help to build trust and accountability, and promote the sustainability of health care services over the long-term.

The Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) model is the main governance model adopted by Indigenous primary health care providers. An ACCHS is an incorporated organisation initiated and based in local Indigenous communities. They deliver a holistic, comprehensive, and culturally appropriate health service to the community. While the capabilities and capacity of ACCHSs vary, this model of care provides important options for Indigenous Australians (Moran et al. 2014).

Data findings

The Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations (ORIC) administers the Corporations (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander) Act 2006 (CATSI Act). The legislation sets out governance standards of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations, and provides a governance of framework that is tailored to suit the needs of Indigenous Australians. The ORIC is also responsible for registering and regulating Indigenous corporations, ensuring that they comply with the CATSI Act, and providing support and advice to help them manage their affairs effectively.

In 2021–22, 674 corporations that identified as having principal activities of health and community services were incorporated under the CATSI Act and were registered with ORIC. Of these, 671 were required to submit annual reports to ORIC under the CATSI Act, and 432 (64%) complied with their obligations (Table D3.13.2).

Governing committees/boards

The Online Service Report (OSR) collects organisation-level information from health care organisations funded by the Australian Government’s Indigenous Australians’ Health Programme (IAHP). In the 2021–22 OSR, 162 of the 211 (77%) Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations reported having a governing committee/board (Table D3.13.3).

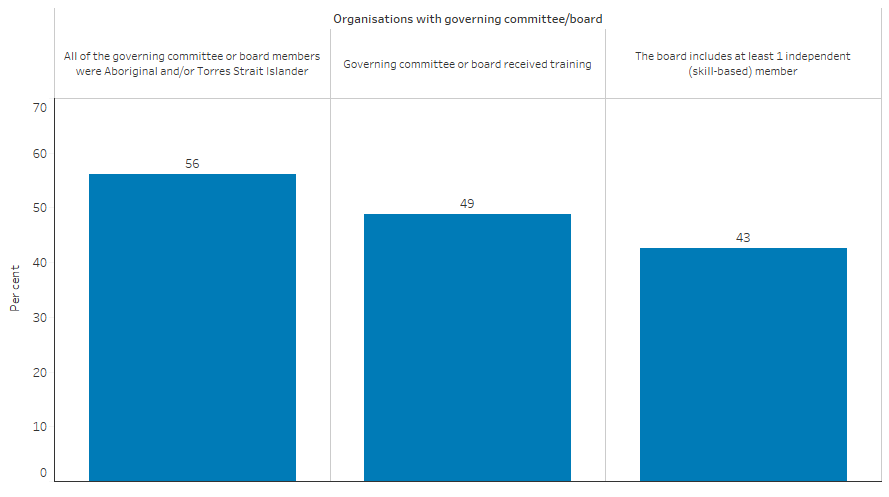

Of these 162 Indigenous primary health care organisations, 79 (49%) of them had governing committee/board members who had received training related to governance issues, 91 (56%) had a committee/board who were all Indigenous Australians, and 69 (43%) had a board that included at least one independent (skill-based) member (Table D3.13.3, Figure 3.13.1).

Figure 3.13.1: Governing committee/board information for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care organisations, 2021–22

Source: Table D3.13.3 and Table D3.13.4. AIHW analyses of Online Services Report data collection, 2021–22.

In 2017–18, 77 of the 79 (97%) Commonwealth-funded organisations providing substance-use services for Indigenous Australians reported having a governing committee/board. Of these 77 organisations, 76 (99%) reported that their committee/board had met as frequently as required of the constitution; 77 (100%) had presented income/expenditure reports to the committee/board on at least two occasions during the year; 47 (61%) had a committee/board who were all Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander people; and 64 (83%) had committee/board members who had received training related to governance issues (Table D3.13.4). Collection of these data ceased after the 2017–18 OSR collection, so no updates are available.

Participation in planning processes

Competent governance also includes participation in planning processes and engagement with community members (see measure 3.08 Cultural competency). Of the 198 Commonwealth-funded Indigenous primary health care organisations in the 2017–18 OSR, 195 (99%) reported having accessible and appropriate client/community feedback mechanisms in place (Table D3.08.14); 125 (63%) had representatives on external boards (such as hospitals); 193 (97%) had participated in organisational planning processes; 164 (83%) had participated in regional health planning processes; and 121 (61%) had participated in state/territory or national policy development (Table D3.13.5). Collection of these data ceased after the 2017–18 OSR collection, so no updates are available.

Research and evaluation findings

Research has identified that Indigenous primary health care services (e.g., ACCHSs) outperform mainstream services, as Indigenous primary health care services are often controlled by their local communities and therefore are underpinned by the values and principles of communities they serve. For example:

- 95% of Indigenous primary health care providers had a formal commitment to providing culturally safe health care (AIHW 2019).

- ACCHSs are more likely than mainstream services to improve the health outcomes of Indigenous Australians (Harfield et al. 2018).

- Many Indigenous clients have a preference for services delivered by ACCHSs rather than mainstream services (AH&MRC 2015).

A study comparing the health outcomes for Indigenous Australians using ACCHSs with the outcomes achieved through mainstream services showed that ACCHSs (Panaretto et al. 2014):

- reflect the patient-centred medical home model (Stange et al. 2010)—the suggested best practice for general practice (Claire 2012; DoHA 2009).

- have a greater than 60% coverage of the Indigenous population outside major metropolitan centres.

- consistently improved performance in key best-practice care indicators.

- performs better than mainstream general practice in several areas, including prevention, chronic disease management, risk factor monitoring, and health assessment.

ACCHSs are found to play a significant role in training the medical workforce and employing Indigenous Australians. ACCHSs have also been found to rise to the challenge of delivering best-practice care, and there is a case for expanding ACCHSs into new areas (Panaretto et al. 2014).

Culture has been found to be a fundamental component of the success of Indigenous primary health care service delivery. Culture is critical to ensuring community participation, enabling Indigenous ownership and governance by engaging communities. Culture is also essential in ensuring the approach to care is culturally appropriate, relevant and holistic, such as traditional healing (Harfield et al. 2018).

The Indigenous Community Governance Project by the Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research and Reconciliation Australia has provided academic rigour to the examination of governance practices. The project provides a framework for negotiation between Australian governments, their agents and Indigenous groups over the appropriateness of different governance processes, values and practices, and over the application of related policy, institutional and funding frameworks within Indigenous affairs (Hunt et al. 2008; SCRGSP 2016).

Evaluations and studies of Indigenous reform initiatives have identified aspects of good practice by governments needed to support the governance of Indigenous organisations. These include:

- long-term contracting to build trust, enhance capacity and afford Indigenous organisations sufficient time to operate in a complex environment,

- good contract management to simplify compliance requirements and reduce transaction costs,

- risk sharing and management through clearer communications and reporting lines,

- working with Indigenous Australians to better understand the complex nature of Indigenous affairs, and ensure their voices are heard in decision-making, research and evaluation, and

- simplified data collection, monitoring and information sharing, based on sound performance and health outcome indicators, using a single reporting framework (Dwyer et al. 2009; OIPC 2006; Yu et al. 2008).

An evaluation of a community engagement strategy, applied across five districts in Perth, found that actively engaging Indigenous communities in decisions about their health care resulted in stronger relationships between community members and health services, improved health services that were more culturally appropriate, and increased access to, and trust in services (Durey et al. 2016).

The Institute for Urban Indigenous Health (IUIH) developed a new regional and systematised model—IUIH System of Care—for how primary care is delivered and intersects with the broader health system. The IUIH System of Care facilitates an integrated approach that engages across local, system and community levels. A review of the IUIH System of Care found improvements in outcomes among Indigenous Australian clients, and that there is the capacity to deliver similar improvements in health access and outcomes in other regions (Turner et al. 2019).

Implications

The data show that the majority of Indigenous primary health care providers are demonstrating sound governance arrangements, including planning processes and having a governing committee/board in place.

However, there is a lack of data to measure other factors of governance, such as the participation of Indigenous Australians in decision-making (SCRGSP 2016).

Making space for Indigenous Australians to define the issues, determine the priorities and suggest solutions for culturally informed strategies that address local community needs is a way to reduce health inequities and has the potential to influence system changes (Crooks et al. 2020). COVID-19 highlighted the unique capacity of ACCHSs to respond rapidly and effectively in a national health crisis. Well before the pandemic was declared by the World Health Organisation (WHO), the sector had mobilised. It commenced planning locally and advocated nationally for border and community closures, access to testing, personal protection equipment, contact tracing capacity and lockdown measures. The partnership between the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) and the Australian Government was critical in supporting Aboriginal communities across Australia to develop local plans. It built on a pre-existing relationship that had effectively responded to syphilis outbreaks (Department of Health 2021).

A key strength of ACCHSs is their ability to respond flexibly to local community needs. This is a result of broadly defined service provisions connected to grant funding allowing considerable discretion in allocating these funds according to their core governance and organisational priorities. It has been suggested that self-determination has led to the development of health services with complex functions that are often a focal point for the community. However, key challenges include meeting the demands placed on Indigenous health services by their constituents and their funders in the face of geographical and other variable factors impacting commercial viability of activities. The certainty and flexibility of the funding granted to ACCHSs allows them to fund core critical staff (offering continuity) for these health services and covers the central expenses of administration and governance (Moran et al. 2014).

Good and effective governance among services can be facilitated by improved coordination among government agencies in their interaction with services, removing duplication of programs and functions, adapting to change, establishing a stable policy environment and effective processes, and learning from evidence drawn from past evaluations (Henry 2007; SCRGSP 2011).

ORIC is enhancing corporate governance within Indigenous corporations by offering comprehensive two and three-day workshops. These Introduction to Corporate Governance workshops, free to attend for directors, future directors, and members of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations registered under the CATSI Act, delve into the foundations of good governance, roles and responsibilities of different corporate positions, financial management, and other pertinent themes. Successful completion of these workshops makes participants eligible for further accredited courses offered by ORIC that aim to continue the development of key personnel within Indigenous corporations.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- AH&MRC (Aboriginal Health & Medical Research Council) 2015. Aboriginal communities improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review on the contribution of Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health. Sydney.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2019. Cultural safety in health care for Indigenous Australians: monitoring framework. Canberra: AIHW.

- Claire LJ 2012. Australian general practice: primed for the "patient-centred medical home". Medical Journal Australia 197:365-6.

-

Crooks K, Casey D & Ward JS 2020. First Nations peoples leading the way in COVID-19 pandemic planning, response and management. The Medical Journal of Australia 213:151-2.e1.

-

Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2021–2031. Government of Australia.

- DoHA (Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing) 2009. Primary Health Care Reform in Australia: Report to Support Australia's First National Primary Health Care Strategy.

- Durey A, McAullay D, Gibson B & Slack-Smith L 2016. Aboriginal Health Worker perceptions of oral health: a qualitative study in Perth, Western Australia. International Journal for Equity in Health 15:4.

- Dwyer J, O'Donnell K, Laviole J, Marlina U & Sullivan P 2009. Overburden Report: Contracting for Indigenous Health Services, The. Overburden Report: Contracting for Indigenous Health Services, The:viii.

-

Finlay S & Wenitong M 2020. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations are taking a leading role in COVID-19 health communication. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 44:251-2.

- Harfield. SG, Davy. C, McArthur. A, Munn. Z, Brown. A & Brown. N 2018. Characteristics of Indigenous primary health care service delivery models: a systemic scoping review. Globalization and Health 14.

- Hawkes DC 2001. Indigenous peoples: self-government and intergovernmental relations. International Social Science Journal 53:153-61.

- Henry K 2007. Creating the right incentives for Indigenous development. The Treasury.

- Hewitt de Alcántara C 1998. Uses and abuses of the concept of governance. International Social Science Journal 50:105-13.

- Hunt J, Smith D, Garling S & Sanders W 2008. Contested governance : culture, power and institutions in indigenous Australia. Canberra: CAEPR.

- Moran M, Porter D & Curth-Bibb J 2014. Funding Indigenous organisations: improving governance performance through innovations in public finance management in remote Australia. (ed., Australian Institute of Health and Welfare). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- OIPC (Office of Indigenous Policy Coordination) 2006. A Red Tape Evaluation in Selected Indigenous Communities: A report by Morgan Disney Associates. Canberra , ACT.

- Panaretto KS, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring IT 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

- SCRGSP (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Services Provision) 2011. Overcoming Indigenous disadvantage: Key indicators 2011. Canberra, Productivity Commission (Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision).

- SCRGSP 2016. Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators 2016. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

- Stange KC, Nutting PA, Miller WL, Jaén CR, Crabtree BF, Flocke SA et al. 2010. Defining and measuring the patient-centered medical home. J Gen Intern Med 25.

- Turner LR, Albers T, Carson A, Nelson C, Brown RB & Serghi M 2019. Building a regional health ecosystem: a case study of the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health and its System of Care. Australian journal of primary health.

- Westbury ND 2002. The importance of Indigenous governance and its relationship to social and economic development. Unpublished Background Issues Paper produced for Reconciliation Australia. Canberra.

- Yu P, Duncan ME & Gray B 2008. Northern Territory Emergency Response: Report of the NTER Review Board. (ed., Government A).