Key messages

- Improving and supporting the participation of Indigenous Australians in tertiary education for health-related disciplines is vital to increasing participation in the health workforce, in which Indigenous Australians are significantly under-represented. Vocational Education and Training (VET) can provide essential pathways for Indigenous Australians to enter tertiary education and the health professions.

- VET enrolment and completion rates of government-funded health-related courses remained higher for Indigenous students than for non-Indigenous students from 2012 to 2021.

- In 2021, rates of VET health-related course enrolments were higher for Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians in all age groups.

- VET completion rates for Indigenous students in government-funded health-related courses fluctuated over the decade 2012 to 2021, decreasing from 18 per 10,000 population in 2012 to 14 per 10,000 in 2013, then increasing to 19 per 10,000 in 2021.

- In 2018, enrolments for health-related higher education courses for Indigenous students were highest for nursing (1,801 enrolments or 67% of enrolments), followed by rehabilitation therapies (278 or 10% of enrolments) and public health, 270 or 10% of enrolments (116 of those in Indigenous health).

- Higher education enrolment rates in health-related courses for Indigenous students increased from 27 to 61 per 10,000 population, between 2001 and 2018.

- Completion rates for Indigenous higher education students in health‑related courses increased from 5 to 11 per 10,000 population, between 2001 and 2018.

- In contrast to the pattern for VET qualifications, Indigenous Australians had lower enrolment and completion rates in higher education than non-Indigenous students. The higher education enrolment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students widened from 17 per 10,000 population in 2001 to 21 per 10,000 in 2018.

- A 2019 systematic review of studies focused on retention issues for Indigenous health students showed that student characteristics such as family and peer support networks were associated with staying in university, and having competing obligations was the most frequently reported barrier, followed by financial hardship. Racism and discrimination were reported as major barriers across multiple studies.

Why is it important?

Health-care professionals have an essential role in delivering health services across a wide range of settings. Training Indigenous Australians in health disciplines contributes to increasing cultural competence within the health-care system. It is vital for health-care professionals to understand and respect the cultural differences and unique history of Indigenous Australians to provide effective and appropriate healthcare. This approach can reduce the ‘cultural chasm’ that has acted as a barrier to effective health outcomes for indigenous peoples (Downing et al. 2011).

Providing training in health-related disciplines to Indigenous Australians is a crucial step towards achieving health equity. The Australian Human Rights Commission has emphasised that the health outcomes of Indigenous Australians are still far below those of non-Indigenous Australians, reflecting systemic inequalities (Holland 2018). Indigenous Australians trained in health-related disciplines and retained in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander primary health care sector enables communities to take charge of their health needs. It fosters a community-driven approach to health that recognises and respects traditional knowledge and healing practices, enhancing community trust and engagement with health services (Reeve C et al. 2015).

Indigenous Australians are significantly under-represented in the health workforce (see measure 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce). Improving and supporting the participation of Indigenous Australians in tertiary education for health-related disciplines is vital to increasing Indigenous Australian participation in the health workforce. Vocational Education and Training (VET) can provide essential pathways for Indigenous Australians to enter tertiary education and the health professions (Gwynne et al. 2019). Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) provide training pathways in a range of management, administrative and health careers (Campbell et al. 2018). They are the primary setting for employment of Indigenous Australians in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker positions and offer pathways for further training and education.

Data findings

Vocational Education and Training

In 2021, there were 7,107 enrolments of Indigenous students in health-related Vocational Education and Training (VET) courses, and 1,772 course completions (on a government-funded or fee-for-service basis) (Table D3.20.9, Table D3.20.11). Females accounted for around three-quarters (77%) of enrolments among Indigenous Australians in VET health-related courses (Table D3.20.40).

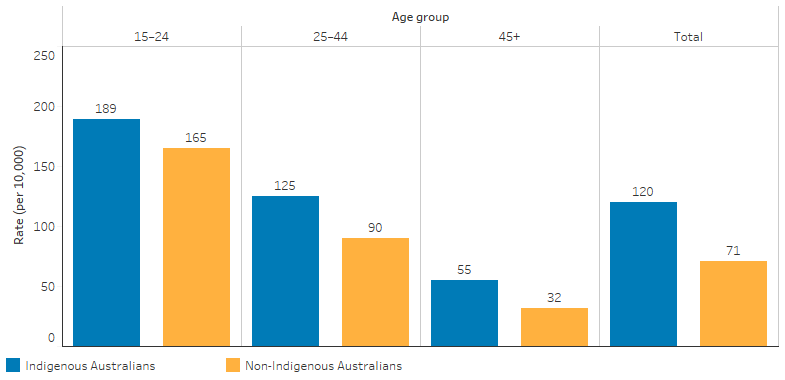

The rate of student enrolments in VET health-related courses was highest for Indigenous Australians aged 15–24 (189 per 10,000), followed by those aged 25–44 (125 per 10,000) and those aged 45 and over (55 per 10,000). Rates of health-related course enrolments were higher for Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians in all age groups (Table D3.20.39, Figure 3.20.1).

Figure 3.20.1: Vocational Education and Training health-related course enrolments, by Indigenous status and age, 2021

Source: Table D3.20.39. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022a).

In 2021, the most common enrolments in VET health-related courses for Indigenous students were public health (2,875 enrolments) and nursing (1,119 enrolments) (Table D3.20.9, Table D3.20-1).

Table 3.20-1: Total Vocational Education and Training health-related course enrolments, by Indigenous status and course, 2021

|

Detailed field of education |

Indigenous Number |

Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

Non-Indigenous Number |

Non-Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Medical studies |

12 |

n.p. |

390 |

0.2 |

|

Nursing |

1,119 |

18.9 |

28,799 |

14.2 |

|

Pharmacy |

11 |

n.p. |

1,143 |

0.6 |

|

Dental studies |

380 |

6.4 |

9,009 |

4.4 |

|

Optical science |

31 |

0.5 |

914 |

0.4 |

|

Public health |

2,875 |

48.5 |

25,336 |

12.5 |

|

Rehabilitation therapies |

39 |

0.7 |

167 |

0.1 |

|

Complementary therapies |

157 |

2.6 |

9,305 |

4.6 |

|

Other health |

2,480 |

41.8 |

69,414 |

34.1 |

|

Total enrolments |

7,107 |

119.8 |

144,477 |

71.0 |

Notes

1. Students may enrol in more than one course.

2. n.p. not published due to concerns about reliability of rates based on small numbers.

Source: Tables D3.20.9. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022a).

In 2021, the most common VET health-related courses completed by Indigenous students in 2021 were public health (804 completions) and nursing (229 completions) (Table D3.20.11, Table 3.20-2).

Table 3.20-2: Total Vocational Education and Training health-related course completions, by Indigenous status and course, 2021

|

Detailed field of education |

Indigenous Number |

Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

Non-Indigenous Number |

Non-Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Medical studies |

4 |

n.p. |

144 |

0.1 |

|

Nursing |

229 |

3.9 |

7,615 |

3.7 |

|

Pharmacy |

4 |

n.p. |

822 |

0.4 |

|

Dental studies |

67 |

1.1 |

2,367 |

1.2 |

|

Optical science |

3 |

n.p. |

167 |

0.1 |

|

Public health |

804 |

13.6 |

10,119 |

5.0 |

|

Rehabilitation therapies |

6 |

n.p. |

28 |

0.0 |

|

Complementary therapies |

29 |

0.5 |

2939 |

1.4 |

|

Other health |

625 |

10.5 |

25,102 |

12.3 |

|

Total completions |

1,772 |

29.9 |

49,296 |

24.2 |

Notes

1. Students may enrol in more than one course.

2. n.p. not published due to concerns about reliability of rates based on small numbers.

Source: Table D3.20.11. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022a).

There were 304 VET qualifications completed in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health worker occupations in 2021. Females accounted for 76% of the completions for students in these courses (Table D3.20.20).

A subject load pass rate is the ratio of hours studied by students who passed their subject/s to the total hours committed to by all students who passed, failed or withdrew from the corresponding subject/s. The VET subject load pass rate for Indigenous students studying health-related courses was 73% (Table D3.20.16).

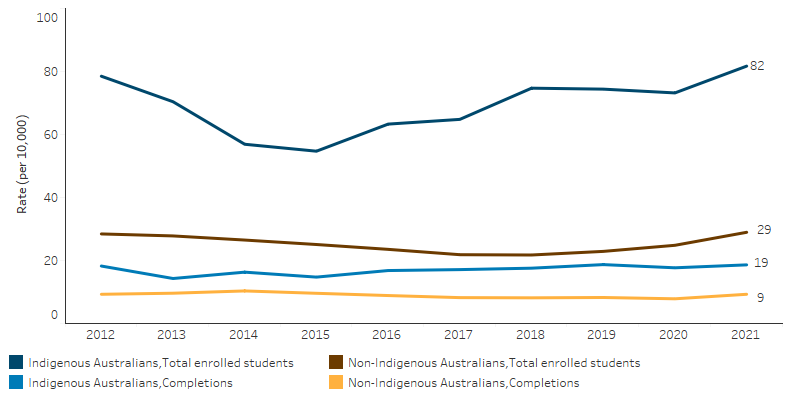

The VET health-related course completion rates for Indigenous students completing government-funded courses fluctuated over the decade from 2012 to 2021, decreasing from 18 per 10,000 population in 2012 to 14 per 10,000 in 2013, then increasing to 19 per 10,000 in 2021. There was also no clear trend in the rate for non-Indigenous students (Table D3.20.23, Figure 3.20.2).

Government-funded VET health-related course enrolment and completion rates remained higher for Indigenous students than non-Indigenous students over the period 2012 to 2021 (Table D3.20.23, Figure 3.20.2).

Figure 3.20.2: Government-funded VET health-related course enrolments and completions, by Indigenous status, students aged 15 and over, 2012 to 2021

Source: Table D3.20.23. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022b).

Higher education for health-related courses

In contrast to the rate of Indigenous students enrolled in and completing VET health-related courses, the rate of Indigenous students enrolled in and completing health-related courses in the higher education section is lower than that of non-Indigenous students.

In the Selected Higher Education Statistics collection for 2018, there were 1,310 commencements and 597 completions for health-related courses for Indigenous students (Table D3.20.1). When considering these figures in terms of rates, there were 24 commencements per 10,000 population and 11 completions per 10,000 population for Indigenous students. These rates were lower compared with those of non-Indigenous students - 29 commencements per 10,000 population and 20 completions per 10,000 population (Table D3.20.7).

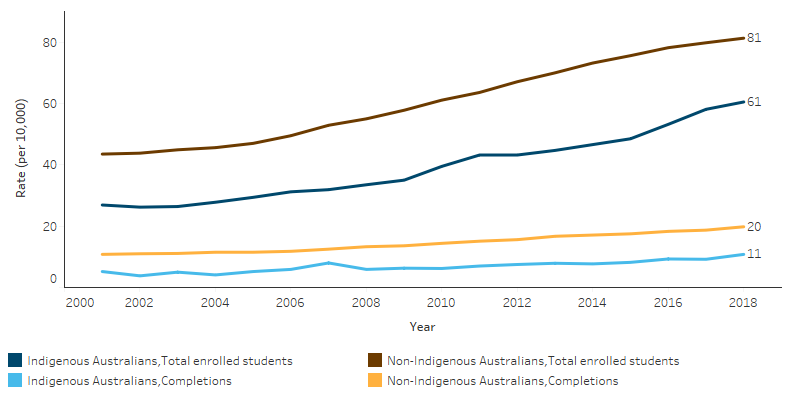

Between 2001 and 2018, enrolment rates for Indigenous students in health-related courses have significantly increased from 27 to 61 per 10,000 population, and completion rates have significantly increased from 5 to 11 per 10,000 population (Figure 3.20.3). Over this period, the enrolment rates for Indigenous students increased at a faster rate than the completion rates (157% compared with 134%).

There was also a significant increase in higher education enrolment and completion rates for non-Indigenous students in health-related courses, resulting in a:

- widening of the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians for health-related course enrolments, from 17 per 10,000 population in 2001 to 21 per 10,000 in 2018, and a

- widening of the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians for health-related course completions, from 5.6 per 10,000 population to 9.0 per 10,000 over the same period (Table D3.20.7).

The completion rate for Indigenous students studying health-related courses in 2018 was 81% compared with 92% for non-Indigenous students (Table D3.20.6).

Figure 3.20.3: Domestic higher education students aged 15 and over enrolled in and completing health-related courses, by Indigenous status, 2001 to 2018

Source: Table D3.20.7. AIHW analysis of Selected Higher Education Statistics (Department of Education).

In 2018, undergraduate health-related course enrolments and completions for Indigenous Australians were highest for nursing, with 1,801 enrolments (33 per 10,000 population aged 15 and over) and 281 completions (5.1 per 10,000 population). This was followed by rehabilitation therapies, with 278 enrolments (5.0 per 10,000 population) and 32 completions (0.6 per 10,000).

Public health accounted for 270 enrolments among Indigenous Australians (4.9 per 10,000), 116 of which were for Indigenous health. There were also 31 completions in public health (0.6 per 10,000) (13 of which were for Indigenous health) (Table D3.20.3, Table D3.20.5, Table 3.20-1, Table 3.20-2).

Table 3.20-3: Undergraduate domestic health-related course enrolments, Indigenous and non-Indigenous students aged 15 and over, 2018

|

Detailed field of education |

Indigenous Number |

Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

Non-Indigenous Number |

Non-Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nursing |

1,801 |

32.6 |

61,121 |

31.5 |

|

Public health |

270 |

4.9 |

9,624 |

5.0 |

|

Indigenous health |

116 |

2.1 |

19 |

0.0 |

|

Medical studies |

211 |

3.8 |

7,687 |

4.0 |

|

Rehabilitation therapies |

278 |

5.0 |

22,051 |

11.4 |

|

Dental studies |

53 |

1.0 |

2,467 |

1.3 |

|

Pharmacy |

36 |

0.7 |

5,375 |

2.8 |

|

Radiography |

40 |

0.7 |

3,686 |

1.9 |

|

Optical science |

<5 |

n.p. |

1,180 |

0.6 |

|

Total undergraduate domestic students(a) |

2,683 |

48.6 |

112,396 |

57.9 |

|

Total enrolments(b) |

3,349 |

. . |

187,051 |

. . |

(a) Only the major course of each student is counted, so a student studying multiple courses is only counted once.

(b) Includes undergraduate, postgraduate, domestic and international students.

Note: n.p. = not published.

Source: Tables D3.20.3. AIHW analysis of Selected Higher Education Statistics (Department of Education).

Table 3.20-4: Undergraduate domestic health-related course completions, Indigenous and non-Indigenous students aged 15 and over, 2018

|

Detailed field of education |

Indigenous Number |

Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

Non-Indigenous Number |

Non-Indigenous Rate (per 10,000) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Nursing |

281 |

5.1 |

12,657 |

6.5 |

|

Public health |

31 |

0.6 |

1,616 |

0.8 |

|

Indigenous health |

13 |

0.2 |

<5 |

n.p. |

|

Medical studies |

27 |

0.5 |

1,535 |

0.8 |

|

Rehabilitation therapies |

32 |

0.6 |

4,216 |

2.2 |

|

Dental studies |

14 |

0.3 |

621 |

0.3 |

|

Pharmacy |

5 |

0.1 |

957 |

0.5 |

|

Radiography |

5 |

0.1 |

677 |

0.3 |

|

Optical science |

<5 |

n.p. |

138 |

0.1 |

|

Total undergraduate domestic students(a) |

394 |

7.1 |

22,149 |

11.4 |

|

Total enrolments(b) |

599 |

. . |

45,584 |

. . |

(a) Only the major course of each student is counted, so a student studying multiple courses is only counted once.

(b) Includes undergraduate, postgraduate, domestic and international students.

Note: n.p. = not published.

Source: Tables D3.20.5. AIHW analysis of Selected Higher Education Statistics (Department of Education).

Undergraduate enrolment rates for Indigenous Australians in health-related courses were lowest in the Northern Territory (25 per 10,000 population) and highest in Victoria (56 per 10,000). The course completion rate for Indigenous Australians in health-related courses was highest in Tasmania (12 per 10,000) (Table D3.20.27).

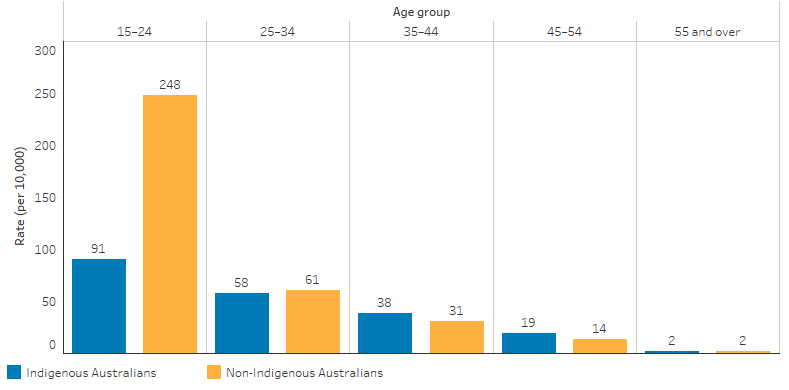

Of the total number of Indigenous Australians enrolled in health-related courses, 83% were females (Table D3.20.26). Undergraduate enrolment rates for health-related courses were lower for Indigenous than non-Indigenous students in the younger age groups (15–34). For those aged 35 and over, the rate was higher for Indigenous students (Table D3.20.2, Figure 3.20.4).

Figure 3.20.4: Undergraduate domestic health-related courses enrolments, by age group and Indigenous status, 2018

Source: Table D3.20.2. AIHW analysis of Selected Higher Education Statistics (Department of Education).

Research and evaluation findings

Interviews conducted with Indigenous students and their parents/carers living in East Gippsland found that the barriers to health careers faced by the students included:

- poor school retention rates;

- negative school experiences including low teacher expectations and culturally insensitive teaching styles;

- lack of information and exposure to role models in the early years of secondary school;

- inappropriate subject choice (low take up of mathematics and science in Years 11 and 12);

- lack of self-belief and confidence;

- a tendency to prefer study in Technical and Further Education (TAFE) rather than in a university;

- family commitments/obligations; and

- the time and financial costs associated with academic study (Paton et al. 2017).

Completion rates for Indigenous Australian students enrolled in health related higher education courses are relatively low compared with non-Indigenous students (Anderson 2011). A study of higher education outcomes of Indigenous students enrolled at regional universities in Queensland and the Northern Territory found that 20% of Indigenous students were studying nursing or other health disciplines. A cohort analysis of the total student group found that more Indigenous women than Indigenous men were staying enrolled and that their completion rates were much higher. However, completion rates for Indigenous students studying at these Queensland and Northern Territory universities were lower than the completion rates for Indigenous students enrolled at all Australian universities. Full-time study intensity was associated with higher qualification completion, and 6% of students were still engaged with their study and working towards qualification completion 10 years after enrolment. Interviews of students and staff identified barriers related to communication, technology and financial support, especially for students in remote locations (Shalley et al. 2019).

Many factors affect the rate of Indigenous Australian student completions (Anderson 2011). A cohort study of Indigenous students commencing bachelor degrees in 2005 showed a completion rate of 46.7% after nine years, while for non-Indigenous students, the completion rate was 73.9% (Edwards & McMillan 2015). More than one in five Indigenous students dropped out before their second year and another quarter had dropped out at some other stage over a nine year period, and 8% were still enrolled after nine years. The 2013 University Experience Survey results showed that 23.9% of Indigenous students had seriously considered leaving university early, compared with 17.6% of non-Indigenous students. Almost half (44%) of the Indigenous students who considered leaving early said that the reason for this was financial difficulties, compared with 29% of non-Indigenous students. Indigenous students were also more likely to indicate that financial circumstances affected their study. In the health sciences, there is a high attrition rate during the early years of higher education, especially in the first year (Anderson 2011). A 2017 study of Indigenous students at the University of Adelaide found that 10% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they would be likely to withdraw from their studies and that there was a positive association between caring responsibilities for parents, children and extended family and likelihood of withdrawal (Hearn et al. 2019).

A 2019 systematic review identified 26 studies focused on retention issues for Indigenous students covering fields of study, including nursing and midwifery, medicine, psychology, and public health (Taylor et al. 2019). Student characteristics such as family and peer support networks were associated with staying in university, and having competing obligations was the most frequently reported barrier, followed by financial hardship. Academic preparation and prior educational experiences were also factors. School and faculty characteristics, including access to the Indigenous Student Support Centre, were reported as providing support, while racism and discrimination were reported as major barriers across multiple studies.

The most successful strategies used by nursing, health and medical science faculties to improve retention of Indigenous students included:

- culturally appropriate recruitment and selection processes

- comprehensive orientation and pre-entry programs

- building a supportive and enabling school culture

- appointing Indigenous academics

- embedding Indigenous content throughout the curriculum

- developing mentoring and tutoring programs

- flexible delivery of content

- partnerships with the Indigenous Student Support Centre

- providing social and financial support

- ‘leaving the door open’ for students to return (Taylor et al. 2019).

While there has been growth in the number of Indigenous students undertaking tertiary nursing courses, there are concerns that the completion rates have not kept pace and the attrition rates remain an issue (Cramer et al. 2018; Kelly & Henschke 2019). A review of growth in the Indigenous nursing workforce in New South Wales and across Australia from 2008 to 2015 recognised the commitment of government policy and funding initiatives but concluded there had been limited effect on growth (Deravin et al. 2017). Interviews conducted with eight final year Queensland Indigenous tertiary nursing students about enablers for successful course completion found a narrative of student experience covering: making a difference; valuing Indigeneity; healing; strength of connections; resisting racism; embracing support; and persevering towards completion (West et al. 2016). The Indigenous nursing students in this study reported experiences of racism and stereotypes from academics and other students, and institutional racism including the policies and practices of the universities and health-care institutions (West 2012; West et al. 2013). This study also conducted interviews with 13 academics from Queensland universities, where it was reported there was sometimes a tendency for Indigenous nursing students to restrict their use of support services to the Indigenous Education Support Unit and Indigenous academics, or for university support services to go unused, and there was a need to raise the profile of the available support services among students. Another study interviewing four Indigenous nursing students found that while they were aware of support services available at the university, they were reluctant to access them, as they did not want to be identified as Indigenous (Kelly & Henschke 2019). Usher and others (2005) did in-depth interviews with 22 Indigenous students enrolled in undergraduate nursing degrees across Australia and found the students faced a number of challenges, including financial hardship; staff insensitivity to cultural issues; discrimination; and a lack of Indigenous mentors (Usher et al. 2005). A later study conducted in-depth interviews and a focus group with five Indigenous Health Workers enrolled in a Bachelor of Nursing at an Australian university (Stuart & Gorman 2015). All participants said that they had often encountered racist remarks during their course, including from other students and hospital staff while on clinical practice. This study also noted the importance of prior Indigenous Health Worker experience being recognised for course exemptions. Participants reported experiencing difficulty in having this recognised, possibly due to a lack of understanding of the Indigenous Health Worker role.

A review of research into enrolled nursing education found that studies focus on higher education, and VET for enrolled nurses is overlooked (Cramer et al. 2018). In Western Australia, 16 Indigenous students in a Diploma of Nursing course found that academic skill assessments and tailored educational support at entry (if needed) can resource students to navigate increasingly complex course content (Slatyer et al. 2016). Course flexibility to help students negotiate study in combination with ongoing family and financial obligations was important, as were strategies to develop resilience and connect with support networks.

Qualitative research conducted in rural and remote New South Wales community mental health services has learnings for the Bachelor of Health Sciences (Mental Health) and traineeship pathway undertaken by Aboriginal mental health workers (AMHW) (Cosgrave et al. 2018). AMHWs working in these services experienced low levels of job satisfaction, especially while undertaking the embedded training program. They had concerns that this qualification was not recognised in the New South Wales Health system, which had negative effects on remuneration and career opportunities. The authors recommended that changes be made to the education component of the AMHW training program and, in particular that the degree qualification be changed to one of the recognised eligible professions for clinical roles.

Over the period 2012 to 2015, Wontulp-Bi-Buya College in Queensland ran the Certificate III in Addictions Management and Community Development and the Certificate IV in Indigenous Mental Health: Suicide Prevention (Stephens & Monro 2019). Two evaluations into the effectiveness of the delivery and the outcomes of these courses found successful course delivery, satisfaction and completion rates above the national average. The Certificate IV course had 60 students, with a 78% completion rate. The evaluation found that graduates of the course developed personal empowerment and a sense of control over their life and had emerged with a set of oral and practical skills to work effectively with service providers in health and community services. The Certificate III course had 140 students, and 57% graduated between 2012 and 2014. A further 15% completed the course but were unable to receive accreditation because they had not paid the entire student contribution fee. The evaluation found the course to be responsive and relevant for the training and applied learning of Indigenous community leaders (Stephens 2014).

A New South Wales vocational education scholarship program was designed for Indigenous students in Certificates III and IV Dental Assisting and Certificate IV in Allied Health Assistance using enablers of success previously identified for Indigenous tertiary nursing students (Gwynne et al. 2019). The enablers were: teachers’ understanding and awareness; relationships, connections and partnerships; institutional structures, processes and systems; and family and community knowledge, awareness and understanding. An evaluation of the program assessed whether these enablers contributed to a very high completion rate for a group of 31 Indigenous Australians enrolled in the program. Twenty students and eight teaching and support staff consented to participate in the evaluation and were interviewed. The evaluation found that the students and staff perceived these enablers as contributing to student success, and identified additional enablers, including employer support and ‘listening and improving’—referring to continuous improvement and students feeling heard when they raised issues. The evaluation concluded that it might be possible to improve the completion rates if VET programs are better designed to meet the cultural, family and learning needs of Indigenous students while recommending a larger study be conducted to inform future design and delivery.

Implications

There has been a significant improvement in health-related higher education course enrolment and completion rates for Indigenous students. However, the gap has widened due to increases in non-Indigenous student enrolment and completion rates. Improving retention and completion rates for Indigenous Australians training for health-related disciplines remains an area of focus.

Strategies are required to increase enrolment in courses for the health disciplines in which Indigenous students are under-represented. There is a need to strengthen VET to higher education pathways, and dual-sector institutions may play a role in this (Frawley et al. 2017). ‘Creative synergies’ may also help. For example, a partnership agreement was developed between a New South Wales university and TAFE for school-based traineeships to be undertaken concurrently with the Higher School Certificate (HSC) for students aspiring to enter nursing programs but who may not achieve the required Australian Tertiary Admission Rank (ATAR) (Kinnane et al. 2014).

Indigenous students are under-represented in undergraduate and VET pharmacy course enrolments and completions. Improving access to and the effectiveness of pharmacy scholarships can help increase Indigenous student participation in pharmacy courses, through mechanisms such as the Seventh Community Pharmacy Agreement which funds the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Pharmacy Scholarship Scheme and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Pharmacy Assistant Traineeship Scheme.

Improvements in secondary school educational retention and attainment are also necessary (see measure 2.05 Education outcomes for young people). In order to design effective initiatives to support Indigenous students in higher education, more attention needs to be directed towards primary students, in addition to secondary students and students already at university (Gore et al. 2017).

The Universities Australia's Indigenous Strategy 2022-2025 recognises the importance of education and training in empowering Indigenous individuals and communities to contribute to a better healthcare system. The key focus areas of the strategy include access and participation, Indigenous leadership and workforce development, research and innovation, and curriculum and cultural safety. By focusing on these key areas, the strategy aims to break down barriers and create a more inclusive and equitable education and training system. This will contribute to the development of a healthcare workforce that is better equipped to address the unique healthcare needs of Indigenous communities and improve health outcomes for Indigenous Australians (Universities Australia 2023).

Some medical schools have been significantly more successful in attracting and retaining Indigenous medical students. These schools have adopted comprehensive approaches, including locally based strategies involving personal contact and community engagement, building relationships with potential students and their families and communities, and Indigenous medical or health support units. Indigenous Australian medical students reported the presence of a support unit as their main reason for choosing a university (57%). The presence of Indigenous staff within the school was also important, along with mentoring, curriculum and cultural safety (Minniecon & Kong 2005). Similarly for nursing, appointing Indigenous nursing academics, building partnerships between nursing schools and Indigenous Education Support Units, and implementing tailored cross-cultural awareness programs for nurse academics have been proposed to enable successful course completions by Indigenous nursing students (West et al. 2014).

The Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (AHPRA) administers the National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (National Scheme). The National Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Cultural Safety Strategy 2020-2025 highlights efforts being made by Australian governments to provide culturally safe and supportive education environments. This includes an ongoing commitment to learning, education and training to achieve a healthcare system free of racism. The AHPRA has emphasised the importance of cultural safety in its codes and guidelines, promoting respect for Indigenous cultures and traditions in educational settings (Australian Health Practitioners Regulation Agency 2019).

Further information on measures to increase the number of Indigenous Australians in the health workforce can be found in measure 3.12 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in the health workforce.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- Anderson I 2011. Indigenous pathways into the professions. Canberra: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Australian Health Practitioners Regulation Agency 2019. The National Scheme’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health and Cultural Safety Strategy 2020-2025.

- Campbell MA, Hunt J, Scrimgeour DJ, Davey M & Jones V 2018. Contribution of Aboriginal Community-Controlled Health Services to improving Aboriginal health: an evidence review. Australian Health Review 42:218-26.

- Cosgrave C, Maple M & Hussain R 2018. Factors affecting job satisfaction of Aboriginal mental health workers working in community mental health in rural and remote New South Wales. Australian Health Review 41:707-11.

- Cramer JH, Pugh JD, Slatyer S, Twigg DE & Robinson M 2018. Issues impacting on enrolled nurse education for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students: a discussion. Contemporary Nurse 54:258-67.

- Deravin L, Francis K & Anderson J 2017. Choosing a nursing career: Building an indigenous nursing workforce. Journal of Hospital Administration 6:27-30.

- Downing R, Kowal E & Paradies Y 2011. Indigenous cultural training for health workers in Australia. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 23:247-57.

- Edwards D & McMillan J 2015. Completing university in a growing sector: Is equity an issue? Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research

- Frawley J, Smith JA, Gunstone A, Pechenkina E, Ludwig W & Stewart A 2017. Indigenous VET to Higher Education pathways and transitions: A literature review. International Studies in Widening Participation 4:34-54.

- Gore J, Patfield S, Fray L, Holmes K, Gruppetta M, Lloyd A et al. 2017. The participation of Australian Indigenous students in higher education: a scoping review of empirical research, 2000-2016. Australian Educational Researcher 44:323-55.

- Gwynne K, Rojas J, Hines M, Bulkeley K, Irving M, McCowen D et al. 2019. Customised approaches to vocational education can dramatically improve completion rates of Australian Aboriginal students. Australian Health Review 44:7-14.

- Hearn S, Benton M, Funnell S & Marmolejo-Ramos F 2019. Investigation of the factors contributing to Indigenous students’ retention and attrition rates at the University of Adelaide. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education:1-9.

- Holland C 2018. A ten-year review: the Closing the Gap Strategy and Recommendations for Reset.

- Kelly J & Henschke K 2019. The experiences of Australian indigenous nursing students: A phenomenological study. Nurse education in practice 41:102642.

- Kinnane S, Wilks J, Wilson K, Hughes T & Thomas S 2014. Can’t Be What You Can’t See: The Transition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students into Higher Education (final report to the Australian Government Office for Learning and Teaching). Sydney.

- Minniecon D & Kong K 2005. Healthy Futures: Defining best practice in the recruitment and retention on Indigenous medical students. (ed., Australian Indigenous Doctors' Association). Canberra: AIDA.

- NCVER (National Centre for Vocational Education Research) 2022a. Total VET students and courses [VOCSTATS]. NCVER. Viewed 19 May 2023.

- NCVER 2022b. Government-funded students and courses [VOCSTATS]. NCVER. Viewed 19 May 2023.

- Paton D, Blaber D, Anderson C, Bundle G, Campbell D, Mitchell E et al. 2017. Increasing the Aboriginal health workforce in East Gippsland.

- Reeve C, Humphreys J, Wakerman J, Carter M, Carroll V & Reeve D 2015. Strengthening primary health care: achieving health gains in a remote region of Australia. Medical Journal Australia 202.

- Shalley F, Smith J, Wood D, Fredericks B & Robertson K 2019. Understanding completion rates of Indigenous higher education students from two regional universities: A cohort analysis. Final Report prepared for the National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Educational Research Grants Program, 2017. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education.

- Slatyer S, Cramer J, Pugh JD & Twigg DE 2016. Barriers and enablers to retention of Aboriginal Diploma of Nursing students in Western Australia: An exploratory descriptive study. Nurse Education Today 42:17-22.

- Stephens A 2014. Training for impact: Building an understanding of community development training and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community development outcomes. Cairns: James Cook University.

- Stephens A & Monro D 2019. Training for life and healing: the systemic empowerment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men and women through vocational education and training. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 48:179-92.

- Stuart L & Gorman D 2015. The experiences of Indigenous health workers enrolled in a Bachelor of Nursing at a regional Australian university. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 11:29-44.

- Taylor EV, Lalovic A & Thompson SC 2019. Beyond enrolments: a systematic review exploring the factors affecting the retention of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health students in the tertiary education system. International Journal for Equity in Health 18:136.

- Universities Australia 2023. Indigenous Strategy 2022-25.

- Usher K, Lindsay D, Miller M & Miller A 2005. Challenges faced by Indigenous nursing students and strategies that aided their progress in the course: A descriptive study. Contemporary Nurse 19:17-31.

- West R 2012. Indigenous Australian participation in pre-registration tertiary nursing courses: an Indigenous mixed methods study. James Cook University, Unpublished PhD thesis. Townsville.

- West R, Foster K, Stewart L & Usher K 2016. Creating walking tracks to success: A narrative analysis of Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander nursing students’ stories of success. Collegian 23:349-54.

- West R, Usher K, Buettner PG, Foster K & Stewart L 2013. Indigenous Australians’ participation in pre-registration tertiary nursing courses: A mixed methods study. Contemporary Nurse 46:123-34.

- West R, Usher K, Foster K & Stewart L 2014. Academic staff perceptions of factors underlying program completion by Australian Indigenous nursing students. The Qualitative Report 19:1.