Key messages

- Infant and child mortality are long-established measures of child health as well as the overall health of the population and its physical and social environment. Numbers of deaths of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) children can be reported nationally, though rates are limited to the 5 jurisdictions considered to have adequate Indigenous status identification – New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory.

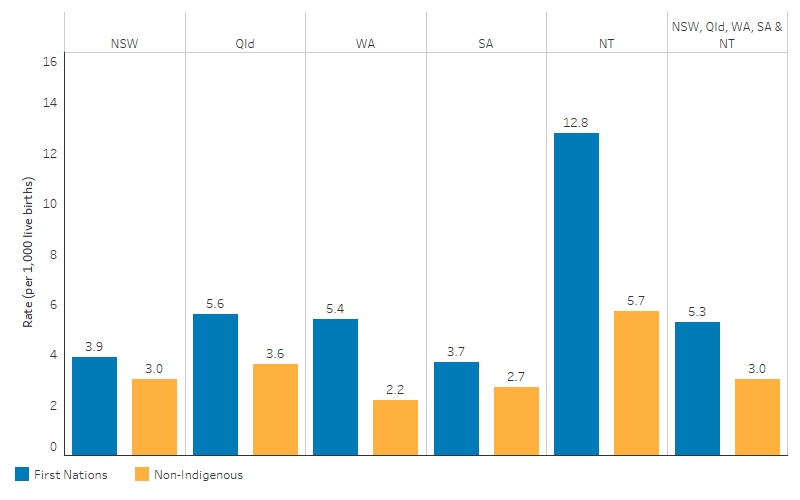

- In 2017–2021, in the 5 jurisdictions combined, the death rate among First Nations infants was 5.3 per 1,000 live births – 1.8 times the rate for non-Indigenous infants (3.0 per 1,000 live births).

- In 2017–2021, in the 5 jurisdictions combined, the death rate among First Nations children aged 0–4 was 145 deaths per 100,000 children – 2.1 times the rate for non-Indigenous children (70 per 100,000 children).

- In 2017–2021, in the 5 jurisdictions combined, certain conditions originating in the perinatal period was the leading cause for First Nations infant deaths (54.2% deaths), followed by signs, symptoms and ill-defined conditions (16.4%), congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (16.2%) and injury and poisoning (5.2%).

- In 2017–2021, injury and poisoning caused 42% of deaths among First Nations children aged 1–4 and accounted for about one-half (49%) of the absolute gap in the death rate between First Nations and non-Indigenous children aged 1–4.

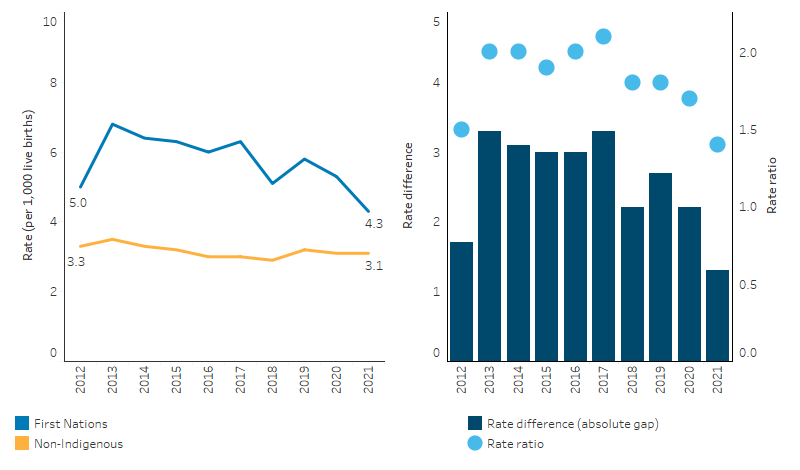

- There were no statistically significant changes in the death rates among First Nations children or infants over the decade from 2012 to 2021. There were also no changes in the gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous infant or child death rates.

- A recent study found that First Nations women receiving continuity of care were more likely to access early antenatal care and have 5 or more antenatal visits, with significantly reduced pre-term births, neonatal nursery admissions, planned caesareans and epidural pain relief, and increased exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital. However, the availability of these models for First Nations women is limited, and little is known about the capacity of large maternity services to implement culturally-specific models of care for First Nations women.

- Injuries are a major component of deaths in the 1–4 year age group. Conclusive evidence of the effectiveness of interventions for injury prevention is currently lacking and more research is needed.

Why is it important?

Infant mortality (death of children under 1 year of age) and child mortality (death of children aged 0–4 years) are long-established measures of child health as well as the overall health of society and the physical and social environment a population of people experience. Australia’s infant and child death rates (for the whole population) have declined over the last 100 years due to improved social and public health conditions. In the first half of the 20th century, there were improvements in sanitation and health education. This was followed by the development of immunisation and, in more recent years, better treatment in neonatal intensive care and interventions for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS). However, there is a large gap in infant and child mortality between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) people and non-Indigenous Australians.

The key risk factors associated with infant and child mortality include low birthweight and pre-term births, maternal health and behaviours (for example, nutrition during pregnancy, smoking and alcohol use), socioeconomic status and access to health services (AIHW 2014a; NIAA 2020). Access to quality medical care, public health initiatives and safe living conditions serve as protective factors and can improve the chances of having a healthy baby (AIHW 2018). Women who are able to eat well, exercise regularly and receive regular antenatal care are less likely to have complications during pregnancy. They are also more likely to give birth successfully to a healthy baby (see measures 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy and 3.01 Antenatal care).

The rates of infant mortality and child mortality for First Nations people need to be understood and interpreted in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and their culture (AIHW 2022a). This history and the ongoing impacts of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and poorer outcomes for First Nations people (Productivity Commission 2023).

Australian government funded antenatal care programs led by Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) for First Nations women have been shown to have an impact on maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal nutrition, and breastfeeding practices, and that this, in turn, can reduce the rates of low birthweight, pre-term birth, and child mortality (AIHW 2014a). The ACCHSs sector plays a significant role in providing comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people, including antenatal programs which have delivered improved outcomes for maternal and child health (Panaretto et al. 2007; Panaretto et al. 2014).

In 2008, the Council of Australian Governments committed to halving the gap in death rates for First Nations children under 5 years by 2018. However, this target was not met.

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including through working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community-controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision making by First Nations communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031, (with infant and child mortality as supporting indicators)

- Target 2: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies with a healthy birthweight to 91 per cent

- Target 4: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children assessed as developmentally on track in all five domains of the Australian Early Development Census (AEDC) to 55 per cent.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement.

‘Healthy babies and children (Age range: 0–12)’ is one of the key life course phases focused on in the Health Plan, and 2 objectives specifically address this age range:

- Objective 4.2. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy babies

- Objective 4.3. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy children.

Both the National Agreement and the Health Plan are discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Burden of disease

Infant deaths (deaths of children aged under 1 year of age) contribute substantially to total years of life lost (YLL) due to premature mortality for First Nations people, accounting for about 10% of the total YLL in 2018. When considering all Australians, infant and congenital conditions accounted for 3.7% of the total YLL in 2018. Infant and congenital conditions were responsible for 82% of YLL for First Nations babies aged under 1. Low birthweight and a short gestation period accounted for 21% of YLL attributable to infant and congenital conditions in this age group (AIHW Burden of Disease database). Over 90% of the total burden due to low birthweight and a short gestation was fatal (5,108 YLL of 5,537 DALY) (AIHW 2022b).

Data findings

The infant and child deaths data in this measure are from the National Mortality Database. The death data are used to provide total number of deaths in Australia (nationally) which include Australian residents of all states and territories. However, national death rates are not published due to concerns around the quality of Indigenous status identification in Victoria, Tasmania and Australian Capital Territory. For 5 jurisdictions (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory), the quality of Indigenous status identification in the deaths data is considered adequate (see ‘Data sources: National Mortality Database’). While the number of deaths are presented nationally, data on death rates are reported only for the 5 jurisdictions with adequate quality on Indigenous status.

Data are reported for the 5-year period 2017–2021 because of small numbers for individual years.

In this measure, death rates for infants (children aged under 1 year of age) are presented per 1,000 live births, while death rates of children (aged 0–4 and aged 1-4) are presented per 100,000 children.

Infant deaths

Nationally, over the 5-year period 2017–2021, there were 562 First Nations infant deaths in Australia.

Considering infant death data for the 5 jurisdictions considered to have adequate quality of Indigenous identification (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory), in 2017–2021 there were 518 First Nations infant deaths, accounting for 92% of all 562 First Nations infant deaths nationally (Table D1.20.4).

In the 5 jurisdictions, in 2017–2021:

- 65% (337) of the 518 First Nations infant deaths were neonatal deaths (occurred within 28 days), compared with 74% (2,234) of all 3,003 non-Indigenous infant deaths.

- the death rate for First Nations male infants was 1.3 times as high as the rate for First Nations female infants (6.0 and 4.6 deaths per 1,000 live births, respectively) (Table D1.20.5).

- the death rate for First Nations infants was 1.8 times the rate of non-Indigenous infants (5.3 and 3.0 per 1,000 live births, respectively) (Table D1.20.4, Figure 1.20.1).

- the death rate was highest in the Northern Territory (12.8 per 1,000 live births), followed by Queensland (5.6 per 1,000 live births), Western Australia (5.4 per 1,000 live births), New South Wales (3.9 per 1,000 live births) and was lowest in South Australia (3.7 per 1,000 live births) (Table D1.20.4, Figure 1.20.1).

Figure 1.20.1: Infant (aged under 1) death rates, by jurisdiction and Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined, 2017–2021

Source: Table D1.20.4. AIHW National Mortality Database.

Child deaths

Nationally, over the 5-year period 2017–2021, there were 663 deaths among First Nations children aged 0–4.

Considering death data of children aged 0–4 in the 5 jurisdictions considered to have adequate quality of Indigenous identification (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory), in 2017–2021 there were 613 deaths of First Nations children, accounting for 92.5% of all 663 First Nations infants deaths nationally (Table 1.20.1).

In the 5 jurisdictions, in 2017–2021:

- there were 613 deaths of First Nations children, corresponding to a rate of 145 deaths per 100,000 children.

- the death rate for First Nations male children was 1.3 times as high as the rate for First Nations female children (163 deaths per 100,000 children compared with 127 deaths per 100,000) (Table D1.20.2).

- the death rate for First Nations children was 2.1 times as high as the rate for non‑Indigenous children (145 per 100,000 children compared with 70 per 100,000 children).

- the death rate for First Nations children was highest for those in the Northern Territory (294 per 100,000), followed by Western Australia (162 per 100,000 children), Queensland (161 per 100,000 children), South Australia (119 per 100,000 children) and was lowest for First Nations children in New South Wales (99 per 100,000 children).

- the death rate for First Nations children in the Northern Territory was 3 times as high as for First Nations children in New South Wales, and 2.5 times as high as for First Nations children in South Australia (Table D1.20.1).

Causes of deaths

This section focuses on the underlying causes of death that includes specific diseases that initiated the events leading directly to death, or the circumstances which produced the fatal injury.

Leading causes of infant deaths

Numbers and rates in this section are for New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined (see Table D1.20.13 for additional national numbers). In 2017–2021, the top 4 broad underlying causes of deaths for First nations infants accounted for over 90% of the 518 deaths in these 5 jurisdictions combined (based on ICD-10 chapters – see Box D1.20.1). These were:

- Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, accounting for 54.2% (281 of 518 deaths) of all infant deaths. Major contributing components of these deaths included, ‘fetus and newborn affected by maternal factors and by complications of pregnancy, labour and delivery’ (26.4% of all infant deaths or 137 deaths), ‘disorders related to length of gestation and fetal growth’ (8.3% or 43 deaths) and ‘respiratory and cardiovascular disorders specific to the perinatal period’ (5.8% or 30 deaths).

- Signs, symptoms and ill-defined conditions, accounting for 16.0% of deaths (83 of 518 deaths), mostly consisting of SUDI (12.4% of deaths, 64 of 518).

- Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities, accounting for 15.8% (82 of 518) of deaths.

- Injury and poisoning, accounting for 5.2% of deaths (27 of 518) (Table D1.20.13).

Comparing broad causes of death between First Nations and non-Indigenous infants in the 5 jurisdictions combined showed that, in 2017–2021:

- the death rate for First Nations infants was higher than non-Indigenous infants in 3 of the 4 leading broad causes – certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (2.9 compared with 1.6 per 1,000 live births), signs, symptoms and ill-defined conditions (0.9 compared with 0.3 per 1,000 live births), and injury and poisoning (0.3 and 0.1 per 1,000 live births).

- for all-causes of death combined, the absolute gap (rate difference) in the death rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous infant deaths was 2.3 per 1,000 live births: the largest absolute difference was for deaths due to certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (a difference of 1.3 per 1,000 live births, which accounted for 54.6% of the total gap), followed by signs, symptoms and ill-defined conditions (0.6 per 1,000 live births, 25.9%), and injury and poisoning (0.2 per 1,000 live births, or 9.1%) (Table D1.20.13).

These broad cause of death data are based on ICD-10 chapters. The data were also analysed using a more detailed grouping that mixes chapters, blocks and specific diseases (see Box 1.20.1).

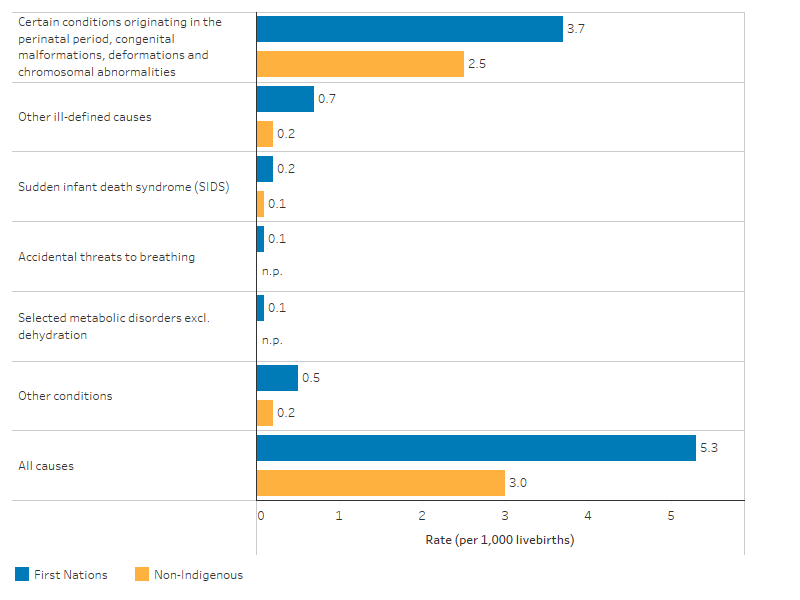

Using this more detailed classification, in 5 jurisdictions combined, the leading specific causes of death for First Nations infants in 2017–2021 were:

- certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (69.9%, 362 deaths of 518 deaths, 3.7 per 1,000 live births)

- other ill-defined causes (12.5%, 65 deaths, 0.7 per 1,000 live births) – this includes: symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, excluding SIDS; and acute or unspecified respiratory failure

- SIDS (3.7%, 19 deaths, 0.2 per 1,000 live births) (Table D1.20.19, Figure 1.20.2).

In 2017–2021, across all the 3 leading causes, the death rates in 5 jurisdictions were higher for First Nations infants compared with non-Indigenous infants. The absolute gap (rate difference) was the largest for certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (1.3 per 1,000 live births), followed by other ill-defined causes (0.5 per 1,000 live births) (Table D1.20.19).

Figure 1.20.2: Leading specific causes of infant death (aged under 1), by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined, 2017–2021

Source: Table D1.20.19. AIHW National Mortality Database.

Leading causes of death for children aged 1–4

Leading causes of death for children aged 1–4 differ to those for infants. In 2017–2021, based on underlying broad causes of death in New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia, and the Northern Territory combined:

- injury and poisoning was the leading cause, accounting for 42% of deaths among First Nations children aged 1–4 (40 of 95 deaths).

- the death rate caused by injury and poisoning for First Nations children aged 1–4 was 2.7 times the rate for non-Indigenous children (11.9 and 4.5 per 100,000 children, respectively).

- deaths due to injury and poisoning accounted for about one-half (49%) of the absolute gap in death rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous children aged 1–4 (Table D1.20.14).

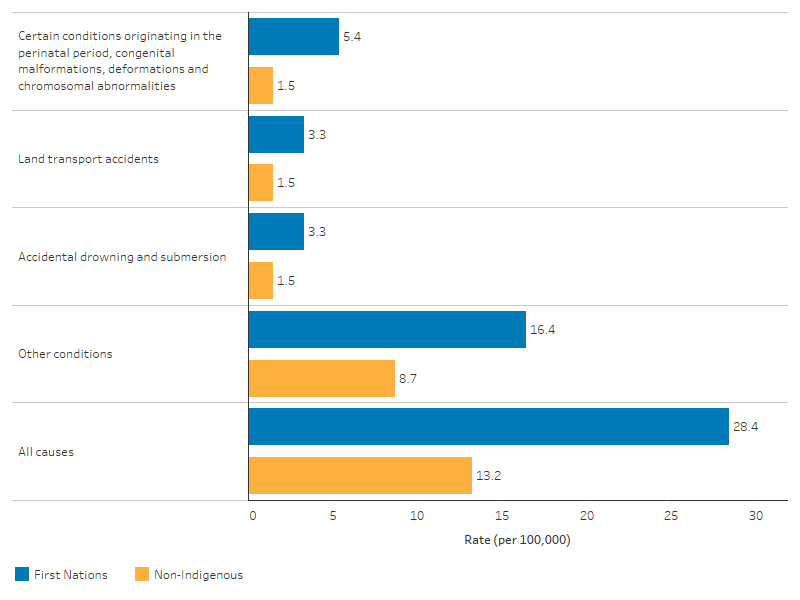

In 2017–2021, the 3 specific leading causes of death for First Nations children aged 1–4 were:

- conditions originating in the perinatal period, congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities (18 of 95 deaths in the 5 jurisdictions combined)

- land transport accidents (11 of 95 deaths)

- accidental drowning and submersion (11 of 95 deaths) (Table D1.20.9).

When comparing the 3 specific leading causes of death for children aged 1–4 by Indigenous status in 5 jurisdictions combined, First Nations children were:

- 3.6 times as likely to die from certain conditions originating in the perinatal period, congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities as non-Indigenous children (5.4 compared with 1.5 per 100,000 children)

- 2.2 times as likely to die from land transport accidents (3.3 compared with 1.5 per 100,000 children)

- 2.2 times as likely to die from accidental drowning and submersion (3.3 compared with 1.5 per 100,000 children) (Table D1.20.19, Figure 1.20.3).

Figure 1.20.3: Leading specific causes of death among children aged 1–4, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined, 2017–2021

Note: Other conditions presented in the figure include diseases and conditions with small counts, and ‘other conditions’ detailed in Table D1.20.19.

Source: Table D1.20.19. AIHW National Mortality Database.

International comparisons

Caution must be used when comparing data with other countries due to variations in data quality, the methods applied for addressing data quality issues and the definitions for identifying the indigenous status of individuals.

International statistics indicate that indigenous infants in the United States and New Zealand have higher death rates than First Nations infants in Australia, though the relative difference in rates between indigenous and other infants is higher in Australia.

- In the United States, the death rate for American Indians/Alaskan Natives infants was 8.1 per 1,000 live births – 1.4 times the rate for the total population (5.8 per 1,000 live births) in the 5-year period 2015–2019 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2023).

- In New Zealand, the infant death rate for Māori people was 5.7 per 1,000 live births – 1.4 times the rate for other infants (4.1 per 1,000 live births) in the 5-year period 2016–2020 (Te Whatu Ora (Health New Zealand) 2022).

In comparison, the death rate for First Nations infants in Australia (for the 5 jurisdictions combined) (5.3 per 1,000 live births) was 1.8 times the rate for non-Indigenous infants (3.0 deaths per 1,000 live births) over the 5-year period 2017–2021 (Table D1.20.13).

Changes over time

To describe trends in mortality data, linear regression has been used to calculate the per cent change over time. This means that information from all years of the specified time period are used, rather than only the first and last points in the series (see Statistical terms and methods). Data presented in this section are for 5 jurisdictions (New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia, South Australia and the Northern Territory) combined.

Over the period of 2012 and 2021, the annual death rate for First Nations infants ranged between 6.8 and 4.3 deaths per 1,000 live births, compared with a death rate for non-Indigenous infants of between 3.5 and 2.9 deaths per 1,000 live births. The change in the death rates among First Nations or non-Indigenous infants was not statistically significant. Also, there were no significant changes in the relative (rate ratio) or absolute gap (rate difference) in the death rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous infants, which showed no consistent trend over the same period (Table D1.20.8, Figure 1.20.4).

Figure 1.20.4: Infant (aged under 1) death rates and changes in the gap, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined, 2012 to 2021

Source: Table D1.20.8. AIHW National Mortality Database

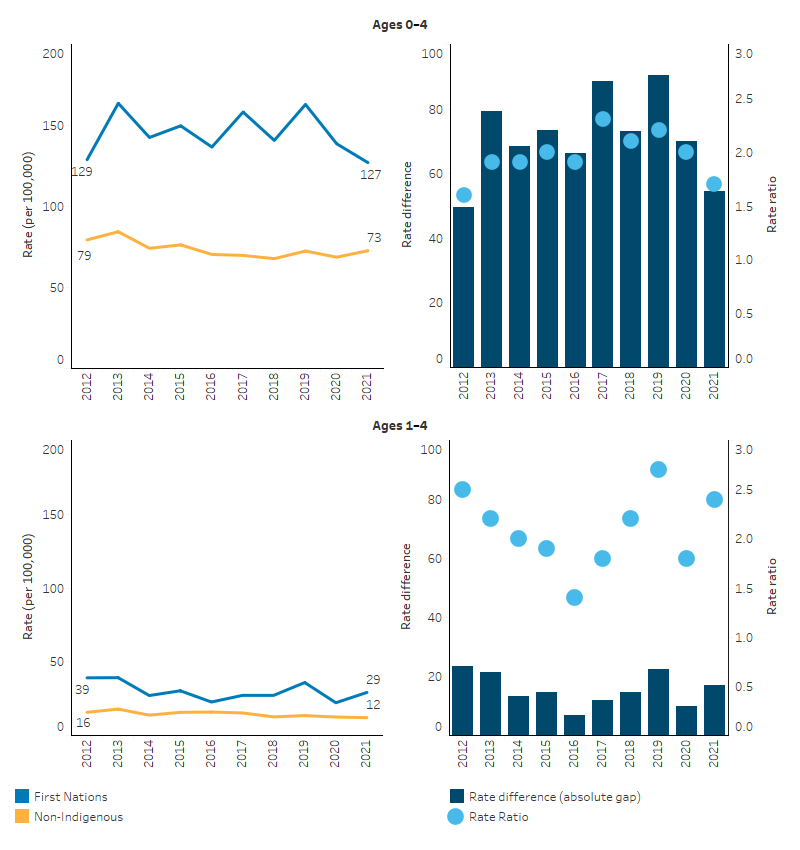

In the years between 2012 and 2021, the annual death rate for First Nations children aged 0–4 ranged between 127 and 164 deaths per 100,000 children, compared with between 68 and 84 deaths per 100,000 for non-Indigenous children. While there was year-to-year variation, there was no statistically significant change in the rate of deaths for First Nations children aged 0–4. For non-Indigenous children over the same period the rate declined by 14%, though there was no statistically significant change in the absolute gap (rate difference) between First Nations and non-Indigenous children. There was also no clear trend in the relative gap between First Nations and non-Indigenous children aged 0–4 over the decade, with rate ratios ranging between 1.6 and 2.3 (Table D1.20.3, Figure 1.20.5).

For First Nations children aged 1–4, there was no significant change in the death rate between 2012 and 2021, nor any significant change in the gap (Table D1.20.18, Figure 1.20.5).

Figure 1.20.5: Death rates and changes in the gap for children aged 0–4 and 1–4, by Indigenous status, NSW, Qld, WA, SA and the NT combined, 2012 to 2021

Source: Tables D1.20.3, D1.20.18. AIHW National Mortality Database.

Research and evaluation findings

Child mortality is associated with a variety of factors such as maternal health (and exposure to both protective and risk factors), quality and access to medical care, socioeconomic conditions and public health practices. The literature suggests that improved access to, and use of, antenatal care services improve outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies. Studies have shown an association between inadequate antenatal care and increased risk of stillbirths, perinatal deaths, retardation of fetal growth, low birthweight and pre-term births (AIHW 2014a; Taylor et al. 2013).

A number of studies and interventions are discussed below that highlight the evidence around addressing child mortality and improving service delivery. Further information on child and maternal health, protective and risk factors, and service delivery responses is also found in other measures of this Framework (see measures 1.01 Birthweight; 1.21 Perinatal mortality; 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy; and 3.01 Antenatal care).

Organisational strategies that incorporate cultural protocols, address social determinants of health, and promote a welcoming environment can enhance First Nations health and wellbeing. Supporting community-controlled health models and developing the First Nations health workforce are crucial for a culturally respectful Australian health system (Freeman et al. 2014).

Sudden Infant Death and related syndromes

Smoking continues to pose a challenge for reducing First Nations infant and child mortality. Researchers found that smoking during lactation and second-hand smoke exposure were associated with increased risk of SIDS (Banderali et al. 2015). Smoking during pregnancy and exposure to second-hand smoke significantly increase the risk of complications that can lead to mortality for both the mother and the developing baby. Cigarette smoke, which contains harmful compounds like nicotine, tar, and carbon monoxide, can cross the placenta, reducing vital oxygen and nutrients. This exposure is associated with a higher chance of miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, pre-term delivery, low birthweight, and serious placental problems, which can be life-threatening. Moreover, smoking during pregnancy is linked to an increased risk of stillbirth and SIDS. Children exposed to cigarette smoke in utero may also face a higher chance of respiratory infections and conditions like asthma and bronchitis. Quitting smoking at any stage of pregnancy can significantly improve outcomes, and avoiding smoking and second-hand smoke exposure during pregnancy and breastfeeding is crucial to minimise these risks (Organisation of Teratology Information Specialists 2023).

A review aimed to explain the role of maternal smoking in the development of sudden fetal or infant death, focusing on SIDS and sudden intrauterine unexplained death syndrome (SIUDS). The study highlighted the physiological abnormalities in infants of mothers who smoked during pregnancy, such as an abnormal response to hypoxia and hypercarbia, reduced arousal responses, and abnormal cardiac function. The study emphasised the harmful effects of tobacco smoke, mainly mediated by carbon monoxide and nicotine, which can enter the fetal circulation and affect multiple developing organs, including the lungs, adrenal glands, and the brain. The study also discussed the neuropathological studies of both SIUDS and SIDS cases, which have highlighted hypoplasia, increased apoptotic figures, and abnormal functioning in several brainstem nuclei, all of which are found to be greater following smoking in pregnancy (Bednarczuk et al. 2020). For more on smoking during pregnancy see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy.

A retrospective cohort study of sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) between First Nations and non-Indigenous infants in Queensland during 2010–2014 examined exposure to SUDI risk factors, to identify factors accounting for higher SUDI mortality among First Nations infants. There were 228 SUDI, of which First Nations infants comprised 26.8%. The First Nations SUDI rate was 2.13 per 1,000 live births compared with 0.72 per 1,000 live births for non-Indigenous infants. The disparity between First Nations and non-Indigenous SUDI was accounted for by sleep surface sharing, smoking, and a combination of antenatal and sociodemographic factors (inadequate antenatal care, young maternal age at first birth and living in outer regional and remote locations). Culturally responsive prevention efforts, including wrap-around maternity care and strategies that reduce maternal smoking and promote safer yet culturally acceptable ways of sleep surface sharing, may reduce First Nations SUDI mortality (Shipstone et al. 2020).

The Pēpi-Pod® Research Study in Queensland involving more than 600 families compared data from all Pēpi-Pod® Program participants from 2012 to 2019. The study targeted families identified as high priority – those with infants with 2 or more risk factors for SUDI, including smoke exposure, prematurity, low birthweight, parental substance and alcohol use, and multiple bed-sharers. Shared sleeping is a valued cultural practice among First Nations communities, often involving infants sharing a sleep surface with family members. The Pēpi-Pod®, inspired by the Wahakura safe sleep basket from New Zealand, provides a dedicated portable sleep space suitable for use in the caregiver’s bed. It also includes personalised education about infant breathing and encourages families to share their learnings within their communities. The primary aim is to decouple smoke exposure and shared sleep, which was associated with the largest proportion of SUDI deaths. In Queensland postcode areas with the highest community participation in the Pēpi-Pod® Program, there was a remarkable 75% reduction in infant mortality. Specifically, the infant mortality rate among the First Nations populations decreased by 46% after the program’s introduction. This significant impact led to an overall 22% reduction in the infant mortality rate across Queensland post-2014. The Pēpi-Pod® Program has proven to be effective in reducing SUDI, especially in the context of known risk factors. It has been shown to be culturally appropriate, feasible, accessible, sustainable, and cost-effective. The program’s success in Queensland, especially among First Nations communities, highlights the importance of culturally sensitive interventions in addressing health disparities (McEniery JA et al. 2022; Young 2022).

Injuries

There is a high burden of child injury and child mortality in remote communities. It has been well documented that injuries resulting from external causes are major causes of death for First Nations children in Australia. Research has found that indigenous children across different communities around the world experience a significantly higher burden of morbidity and mortality from unintentional injuries. Most of these injuries, such as burns, poisoning and transport injuries, are highly preventable. The risks of these injuries are increased by high exposure to hazards in the living environment, socioeconomic disadvantage, lack of means of protection, and living in remote areas (Lee et al. 2018; Möller 2017; Möller et al. 2016a; Möller et al. 2016b; Möller et al. 2015; Möller et al. 2019).

International population-based studies have shown the increased risk of fatal infant injuries for children born with low birthweight, premature birth and other sociodemographic factors. The risk of injury throughout childhood (mainly before 12 years of age) increased with decreasing gestational age and birthweight. This suggests an opportunity to identify children who may benefit from injury prevention (Jain et al. 2001; Sun et al. 2023). Children born prematurely or of low birthweight are frailer and have slower cognitive development, which may put them at a higher risk of injury. There are limited injury prevention programs developed for First Nations children in Australia, and there is a paucity of data to inform the development of appropriate First Nations child injury prevention programs (Möller et al. 2016a).

However, Australian evidence shows that family and community wellbeing were protective against child injury, with programs and services to support caregivers’ wellbeing leading to improvement in injury prevention for the child (Thurber et al. 2018).

A review by Margeson & Gray aimed to identify interventions from 1996 to 2016 that focused on preventing injuries in indigenous children from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Globally, indigenous children are at a higher risk of injury compared to their non-Indigenous counterparts, and mainstream prevention strategies often fall short in indigenous communities. The review analysed 191 records and identified 6 interventions that met the inclusion criteria. These interventions primarily centred on education and awareness to promote child safety. Out of the 6 studies, 3 measured changes in injury hospitalisation rates, with most reporting a significant decrease. All studies that assessed awareness noted positive changes. The success of these interventions was attributed to their culturally appropriate delivery. However, challenges such as staff turnover and the need for experienced staff with indigenous knowledge were identified. The review underscores the positive impact of culturally appropriate interventions, emphasising the significance of indigenous community involvement in shaping initiatives and policies, which not only enhances their effectiveness but also upholds indigenous rights to self-determination and cultural preservation. While there is promising evidence supporting these interventions, definitive conclusions are challenged by varied, small-scale evaluations. The broader context highlights the complex nature of indigenous health, rooted in historical injustices, emphasising the need for a deep understanding of the effects of poverty and marginalisation (Margeson & Gray 2017).

Role and efficacy of health services

Health services play a critical role in the reduction of major risk factors for child mortality. A systematic review of maternal and child health and wellbeing (MCH) programs, highlighted the importance of community health services for the health of First Nations mothers and babies (Jongen et al. 2014). It was found that being community-based or community-controlled is an important factor in the success of First Nations MCH programs around Australia.

Another study identified that involving First Nations women in decisions about their health care was a feature of quality care. It was noted that ACCHSs were better placed than mainstream services to be able to address these barriers through delivering care that meets First Nations women’s social, practical and health care needs, and by having strong links with the community (Hunt 2006).

Increasing the uptake of antenatal care, particularly in the first trimester, is associated with improved maternal health and positive child health outcomes – both soon after birth and later in life. However, there is a disparity in the timing and frequency of antenatal care accessed by First Nations women (see measure 3.01 Antenatal care). This has been attributed to factors such as geographic isolation, cost, language barriers, inefficient communication, a lack of continuity of care, and culturally inappropriate or unsafe services (Sivertsen et al. 2020).

The New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services program, funded by the Australian Government, aimed to increase access to, and use of, child and maternal healthcare services for First Nations families. A review of the New Directions program found that New Directions organisations saw improvements in 7 out of 8 maternal and child health measures, compared with 4 out of 8 measures for non-New Directions organisations. Areas of improvements include the proportion of first antenatal visits before 13 weeks of pregnancy, birthweight recorded, child health assessment, adult health assessment, child immunisations at age 1 recorded, immunisations at age 2 recorded and immunisations at age 3 recorded. The only measures that did not improve were the proportion of babies recording normal birthweights (AIHW 2014b). The New Directions program was consolidated into comprehensive primary health care funding on 1 July 2019.

A study was conducted on the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) and its role in fostering the self-efficacy of First Nations women. Drawing inspiration from the U.S.A Nurse-Family Partnership Program, the ANFPP seeks to improve pregnancy, birth, and early childhood outcomes for First Nations children. Central to its effectiveness is the cultivation of culturally safe relationships, emphasising trust and connection, which promote behaviour change, skill enhancement, and personal growth. The program’s community-centric approach, accentuated by its continuity of care and integration with specialised Midwifery Group Practices, provides a comprehensive support framework for families. Peer support, especially during community days, emerges as a pivotal element, granting women a sense of community and shared experiences. Despite its merits, high staff turnover can lead to high program attrition rates, because in the absence of strong relationships, families disengage. On average, 60% of women leave the program before its completion in Australia. The study also highlights that traditional self-efficacy theories might not adequately represent the collectivist and relational values central to First Nations communities such as First Nations ways of knowing, being and doing, advocating for a more nuanced understanding in future research (Massi et al. 2023).

A study by Singer and others analysed medical records from the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network (SCHN) over a span of 5 years from 2011 to 2015. The aim was to determine the case fatality rate (CFR) for both First Nations and non-Indigenous children admitted to children’s hospitals in New South Wales and to identify predictors of this CFR. Out of 241,823 presentations during the period, the CFR for First Nations children was found to be 2 times that of non-Indigenous children (0.4% vs. 0.2%). First Nations children under the age of 2 and those from remote and regional Australia were at the highest risk of excess mortality. The study found that the highest mortality rates for First Nations children were observed among infants, neonates, and those from outer regional and remote areas with circulatory or perinatal conditions. Despite First Nations children constituting 16% of the study sample, they accounted for 38% of deaths, suggesting potential issues with late presentations, delayed transfers from regional hospitals, or differential treatment within the hospital, including potential institutional racism. The research underscores the need for heightened awareness among healthcare staff of the increased mortality risk in young First Nations children and calls for further research on interventions to reduce mortality and address health inequities (Singer et al. 2019).

Evaluations of community-led approaches

In 2013, a multi-agency partnership between 2 ACCHSs and a Brisbane tertiary maternity hospital co-designed the Birthing in Our Community service (BiOC), which aimed to improve health outcomes and reduce pre-term birth (Kildea et al. 2021). An analysis of the clinical effectiveness of the BiOC service for women who gave birth to a First Nations baby at this hospital during January 2013–June 2019 found that women who received the BiOC service were more likely to access early antenatal care and have 5 or more antenatal visits, with significantly reduced pre-term births, neonatal nursery admissions, planned caesareans, and epidural pain relief, and increased exclusive breastfeeding on discharge from hospital. The results suggest that improving health outcomes of mothers and babies and reducing pre-term birth is possible when First Nations women are targeted early in their pregnancies for antenatal care, through:

- providing culturally safe continuity of care;

- providing a holistic service;

- providing a service with high levels of community investment (collective understanding and valuing of a program), ownership (the program is ‘ours’), and activation (high-level of community participation);

- health service leadership across partner organisations; and

- strengthening the First Nations workforce.

Panaretto et al. (2005) evaluated the effect of a community‐based, collaborative, shared antenatal care intervention (the Mums and Babies program) for First Nations women at the Townsville Aboriginal and Islander Health Service (community-controlled). This program was based on continuity of care, cultural currency and a family‐friendly environment. Women in the intervention group had significantly more antenatal care visits, and improved timeliness of the first visit. There were significantly fewer pre-term births in the intervention group. This study showed that integrated services delivered in a culturally aware and safe environment increased access to antenatal care in the First Nations community. It is possible for this model to be adapted to other urban centres that have significant First Nations populations, community‐controlled health services and with multiple providers of antenatal care (Panaretto et al. 2005).

A follow-up study also showed that the Townsville Mums and Babies program sustained these improvements, and later improved perinatal outcomes for participants, with the reduction in pre-term births later translating into reduced perinatal mortality. Among Townsville-based participants, there was also an increase in mean birthweight, compared with the control group (prior to the start of the program) (Panaretto et al. 2007).

The Child Injury Prevention Partnership (CHIPP) is a community-led solution to prevent First Nations child injury and is a partnership between several organisations working to develop a culturally safe child injury prevention program tailored to meet the needs of families with First Nations children in Walgett, New South Wales. The CHIPP project was funded by a grant from the Australian Prevention Partnership Centre. The program was co-designed and delivered through existing playgroup Goonimoo Mobile Children’s Services (Goonimoo means “mother breast/to nurture”) at the Walgett Aboriginal Medical Service Limited (WAMS). As a result of the program, parents felt that their knowledge, skills, and capacity to prevent and manage child injury within their homes and communities was improved, and the importance of safety was encouraged at the individual, family, organisational and community levels. The message that child safety is everybody’s business was a core theme of the project. Safer environments were advocated for to improve child safety – for example, a WAMS child car seat policy for transporting children across all its services; and Goonimoo implemented a policy on safe arrivals for children at the centre. The CHIPP program highlights the positive impact of investing time and resources to work with communities to build local capacity to deliver child injury prevention programs. The success of the program was largely driven by the strength and expertise at Goonimoo Mobile Children’s Service, and the importance of delivering the program through a trusted and experienced ACCHS (APPC 2022).

The Buckle-Up Safely: Safe Travel for Aboriginal Children and the Safe Homes Safe Kids programs were community-based and community-led initiatives in New South Wales, aimed at enhancing the safety and wellbeing of First Nations children and families. The Buckle-Up Safely program, developed in the Shoalhaven area with support from the Aboriginal Education Consultative Group, focused on increasing the use of child car restraints among First Nations children. This initiative encompassed professional development for educators, informative sessions for parents, and access to subsidised restraints and authorised fitting stations. An evaluation of its pilot phase, involving a pre-test/post-test trial with 71 families, indicated that children in the Shoalhaven group were more than twice as likely to be optimally restrained compared to the control group. Success was attributed to community engagement and support, though challenges such as staff turnover and financial constraints for families were noted. Having expanded to 12 communities across New South Wales, the program underscores the significance of sustained community engagement and addressing economic barriers. The "Safe Homes Safe Kids" program, developed by the Illawarra Aboriginal Medical Service, served disadvantaged First Nations families in the Illawarra region. Delivered by First Nations Family Workers, it offered safety education, resources, and in-home support, fostering trusting relationships. An evaluation involving 51 participants from 17 households reported high satisfaction, improved safety knowledge and skills enhancement, and there were also reports of child injuries being prevented, and changes occurring in the home safety environment. The program’s success was linked to its cultural appropriateness, the comprehensive support from First Nations Family Workers, and the holistic service delivery model of the Illawarra Aboriginal Medical Service. Nonetheless, the program faced hurdles in the availability of trained workers, the cost of safety kits, and participant numbers. Its achievements highlight the critical role of ongoing monitoring, evaluation, and feedback in ensuring program sustainability and innovation (Clapham et al. 2019).

Implications

There was no significant change in the First Nations child mortality rate between 2012 and 2021, nor in the gap with non-Indigenous child mortality. The magnitude of grief and loss experienced by First Nations people through loss of land, language, cultural practices, significantly higher mortality rates, suicide, incarceration and health related problems, has significantly impacted on their social and emotional wellbeing (Wynne-Jones et al. 2016). Policy makers and service providers need to acknowledge this impact and work on culturally appropriate prevention strategies to reduce infant and child mortality.

Young child mortality is also a reflection of the health system’s failure to provide health care to mothers and their babies. First Nations young child and infant mortality may decline with strategies targeting the protective factors and risk factors associated with maternal and child health. Protective factors include the use of culturally-safe antenatal, maternal and child health care.

A continued focus on maternal and child health services to deliver culturally safe, trauma informed continuity of care for mothers and babies during the perinatal period is needed. A key component of improving pregnancy outcomes is early and ongoing engagement in antenatal care, which is facilitated by the provision of culturally safe and evidence-based care relevant to the local community (Clarke & Boyle 2014). These services also need to be geographically accessible and offer outreach services and home visits and provide continuity of care and integration with other services (AHMAC 2012). Strategies addressing modifiable risk factors (such as smoking, alcohol and substance use) as well as fostering positive health behaviours (such as healthy diet and exercise) should be an important focus of antenatal care delivery (see measures 1.01 Birthweight; 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy; and 3.01 Antenatal care).

There has been an increase in First Nations mothers attending antenatal care in the first trimester, a slight increase in attendance at 5 or more antenatal sessions, and a decrease in smoking during pregnancy (AIHW 2023). However, progress in these indicators has not yet been sufficient enough to be translated into a stronger improvement in the First Nations child mortality rate. Further research is needed to better understand the reasons why (including data linkage providing information on the journey of First Nations women throughout the health system from preconception to pregnancy and from antenatal care to birth outcomes and child health outcomes). With regards to birthweight, the HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies presents more detailed statistical analysis on low birthweight including trend analysis of gestational age (pre-term, early-term, full-term births), birthweight and key contributing factors such as maternal health, smoking during pregnancy and antenatal care attendance. It also provides analysis of the level of improvement required in smoking rates to meet the birthweight target in the National Agreement.

Preconception care, typically through primary health care, can be an important avenue to address risk factors for women of reproductive age, including improving reproductive health literacy. However, time constraints and competing priorities for preventive health in the primary health care setting, along with service gaps, indicate preconception care is underutilised, particularly among First Nations women at the younger and older ends of reproductive age. The comprehensive primary health care model employed by ACCHSs has been shown to increase access to preventive health activities. A study in a very remote ACCHS setting showed high engagement with antenatal care in the first 12 weeks of pregnancy among women who received preconception care. Integrating preconception care into existing clinical practice with existing Medicare items such as health assessments and chronic disease management will provide more opportunities for brief interventions, along with upskilling and support of care providers within a comprehensive primary health care context (Griffiths et al. 2020).

First Nations children suffer a disproportionately high burden of unintentional injury. The Australian Government is developing the National Strategy for Injury Prevention 2024–2034, which will include First Nations people as a priority population with regard to injury prevention, and will note that First Nations children are a particularly at-risk population when it comes to injury. The strategy is advancing towards its final stages and it is anticipated to be released by mid-2024.

The Health Plan, released in December 2021, is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap health targets and priority reforms. States, territories and other implementation partners can take flexible approaches to implementing Health Plan priorities. Their approaches will depend on local needs and priorities, led by First Nations people and communities (Department of Health 2021).

Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths-based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure a strong start to life. Comprehensive, wrap-around, community-led Birthing on Country (BoC) services have the potential to support healthy pregnancies and should be explored as a way to offer an integrated, holistic and culturally safe model of care. For example, BoC services can support reduction and cessation of smoking in pregnancy through health-literacy approaches (Department of Health 2021).

Research has shown that BoC models of care, which offer culturally safe, continuous midwifery care for First Nations women, improve birth outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies (such as improving frequency of antenatal care visits and reducing the likelihood of pre-term birth). The Australian Government is actively promoting the BoC model, especially in rural and remote areas where birthing outcomes can be challenging. To support this, the Australian Government has committed $45 million over 4 years (2021–22 to 2024–25) under the Healthy Mums, Healthy Bubs initiative to enhance the maternity health workforce and support BoC practices. This includes $12.8 million to expand the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program from 13 to 15 sites. Additional funding ($22.5 million) has also been allocated over 3 financial years (2022–23 to 2024–25) for the establishment of a BoC Centre of Excellence at Waminda in Nowra, New South Wales. The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) also funded The Birthing on Country: RISE SAFELY study with $5 million, which will establish exemplar BoC services in 3 rural, remote and very remote settings. The study is First Nations led, co-designed and staffed. More broadly, the Department of Health and Aged Care is partnering with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to develop a maternal and child health model of care to enable First Nations mothers and families to access consistent, culturally safe and effective care (NIAA 2023).

The Connected Beginnings Program, funded by the Australian Government, aims to support the early life development of First Nations children. The program focuses on enhancing First Nations families’ engagement with health, early childhood education, and maternal services. It integrates local support services, allowing families to access culturally appropriate resources, with the goal of ensuring that children are safe, healthy, and prepared to thrive at school by the age of 5. The program is community-owned and led, emphasising collaboration with First Nations communities across various sites in Australia.

Australian governments are investing in a range of initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. Descriptions are included in the Policies and strategies section and include the National Tobacco Campaign’s Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program, the iSISTAQUIT program, Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy: 2019 and Beyond, and the National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan. See also measures 1.01 Birthweight; 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy; and 3.01 Antenatal care.

Enhanced primary care services and continued improvement in, and access to, culturally appropriate antenatal care has the capacity to support improvements in the health of the mother and baby. This highlights the important role ACCHSs have in leading culturally safe and responsive health care within their communities (Panaretto et al. 2014). ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. The Australian Government committed to building a strong and sustainable First Nations community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people across the country under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Further work to ensure mainstream services can provide culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations people is also critically important and relates to Priority Reform Three of the National Agreement. These 2 dimensions of health care for First Nations people have been emphasised in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course.

As part of the National Agreement, the health sector was identified as one of 4 initial sectors for a joint national strengthening effort and the development of a 3-year Sector Strengthening Plan. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) was developed in 2021, to acknowledge and respond to the scope of key challenges for the sector, providing 17 transformative sector strengthening actions. Developed through strong consultation across the First Nations community-controlled health sector and other First Nations health organisations, the Health-SSP will be used to prioritise, partner and negotiate beneficial sector-strengthening strategies.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council) 2012. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Antenatal Care – Module 1. (ed., Department of Health and Ageing). Canberra: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2014a. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014b. New Directions: Mothers and Babies Services—assessment of the program using nKPI data—December 2012 to December 2013. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2018. Closing the Gap targets: 2017 analysis of progress and key drivers of change. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Determinants of health for Indigenous Australians. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW, Australian Government.

- AIHW 2023. Australia's mothers and babies. Canberra: AIHW.

- APPC (Australian Prevention Partnership Centre) 2022. Child Injury Prevention Partnership report (CHIPP). The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre (APPC).

- Banderali G, Martelli A, Landi M, Moretti F, Betti F, Radaelli G et al. 2015. Short and long term health effects of parental tobacco smoking during pregnancy and lactation: a descriptive review. Journal of translational medicine 13:327.

- Becker R, Silvi J, Ma Fat D, L’Hours A & Laurenti R 2006. A method for deriving leading causes of death- external site opens in new window. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 84:297–304.

- Bednarczuk N, Milner A & Greenough A 2020. The Role of Maternal Smoking in Sudden Fetal and Infant Death Pathogenesis. Front Neurol. 23.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2023. Infant Deaths: Linked Birth / Infant Death Records. Viewed 18 August 2023.

- Clapham K, Bennett-Brook K, Hunter K, Zwi K & Ivers R 2019. Active and Safe: Preventing unintentional injury to Aboriginal children and young people in NSW: Guidelines for Policy and Practice. Sydney: Sydney Children's Hospital Network.

- Clarke M & Boyle J 2014. Antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australian Family Physician 43:20-4.

- Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2021–2031. Canberra: Australian Government of Department of Health.

- Freeman T, Edwards T, Baum F, Lawless A, Jolley G, Javanparast S et al. 2014. Cultural respect strategies in Australian Aboriginal primary health care services: beyond education and training of practitioners. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 38:355-61.

- Griffiths E, Marley JV & Atkinson D 2020. Preconception Care in a Remote Aboriginal Community Context: What, When and by Whom? International journal of environmental research and public health 17:3702.

- Hunt J 2006. Trying to make a difference: a critical analysis of health care during pregnancy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australian Aboriginal Studies:47.

- Jain A, Khoshnood B, Lee K & Concato J 2001. Injury related infant death: the impact of race and birth weight. Inj Prev 7:135-40.

- Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R & Tsey K 2014. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander maternal and child health and wellbeing: a systematic search of programs and services in Australian primary health care settings. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 14:251.

- Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, Nelson C, Kruske S, Carson A et al. 2021. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial. The Lancet Global Health 9:e651-e9.

- Lee C, Hanly M, Larter N, Zwi K, Woolfenden S & Jorm L 2018. Demographic and clinical characteristics of hospitalised unintentional poisoning in Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal preschool children in New South Wales, Australia: a population data linkage study. BMJ Open 9.

- Margeson A & Gray S 2017. Interventions Aimed at the Prevention of Childhood Injuries in the Indigenous Populations in Canada, Australia and New Zealand in the Last 20 Years: A Systematic Review. International journal of environmental research and public health 14:589.

- Massi L, Hickey S, Maidment S-J, Roe Y, Kildea S & Kruske S 2023. “This has changed me to be a better mum”: A qualitative study exploring how the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy. Women Birth 36(6):e613-e22.

- McEniery JA, Young J, Cruice DC, Archer J & JMD T 2022. Measuring the effectiveness of the Pēpi-Pod® Program in reducing infant mortality in Queensland. Queensland: Published by the State of Queensland (Queensland Health).

- Möller H 2017. Inequalities in unintentional injury hospitalisation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal children in New South Wales, Australia. University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia.

- Möller H, Falster K, Ivers R, Falster M, Randall D, Clapham K et al. 2016a. Inequalities in Hospitalized Unintentional Injury Between Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal Children in New South Wales, Australia. Am J Public Health 106:899-905.

- Möller H, Falster K, Ivers R, Falster MO, Clapham K & L J 2016b. Closing the Aboriginal child injury gap: targets for injury prevention. Aust N Z J Public Health 41:8-14.

- Möller H, Falster K, Ivers R & Jorm L 2015. Inequalities in unintentional injuries between indigenous and non-indigenous children: a systematic review. Injury prevention 21:e144-e52.

- Möller H, Ivers R, Clapham K & Jorm L 2019. Are we closing the Aboriginal child injury gap? A cohort study. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 43:15-7.

- NIAA 2020. Closing the Gap Report 2020. Canberra: National Indigenous Australians Agency.

- NIAA 2023. Commonwealth Closing the Gap Implementation Plan 2023. Canberra: National Indigenous Australians Agency,.

- Organisation of Teratology Information Specialists 2023. Cigarette Smoke.

- Panaretto K, Lee H & Mitchell M 2005. Impact of a collaborative shared antenatal care program for urban Indigenous women: a prospective cohort study. The Medical Journal of Australia 182:514-9.

- Panaretto K, Mitchell M, Anderson L, Larkins S, Manessis V, Buettner P et al. 2007. Sustainable antenatal care services in an urban Indigenous community: the Townsville experience. Medical Journal of Australia 187:18-22.

- Panaretto K, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring I 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

- Productivity Commission 2023. Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report July 2023.

- Shipstone RA, Young J, Kearney L & Thompson JMD 2020. Prevalence of risk factors for sudden infant death among Indigenous and non‐Indigenous people in Australia. Acta Paediatr 109:2614-26.

- Singer R, Zwi K & Menzies R 2019. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in aboriginal children admitted to a tertiary paediatric hospital. International journal of environmental research and public health 16:1893.

- Sivertsen N, Anikeeva O, Deverix J & Grant J 2020. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family access to continuity of health care services in the first 1000 days of life: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Health Serv Res 20:829-.

- Sun Y, Hsu P, Vestergaard M, Christensen J, Li J & Olsen J 2023. Gestational age, birth weight, and risk for injuries in childhood. Epidemiology 21:650-7.

- Taylor LK, Lee YY, Lim K, Simpson JM, Roberts CL & Morris J 2013. Potential prevention of small for gestational age in Australia: a population-based linkage study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 13:210.

- Te Whatu Ora (Health New Zealand) 2022. Fetal and Infant Deaths web tool.

- Thurber K, Burgess L, Falster K, Banks E, Möller H, Ivers R et al. 2018. Relation of child, caregiver, and environmental characteristics to childhood injury in an urban Aboriginal cohort in New South Wales, Australia. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 42:157-65.

- Wynne-Jones M, Hillin A, Byers D, Stanley D, Edwige V & Brideson T 2016. Aboriginal grief and loss: a review of the literature. Australian Indigenous HealthBulletin 16(3), July 2016 – September 2016.

- Young J 2022. The Pēpi-Pod® Program: Preventing sudden unexpected death in infancy.