Key messages

- In 2020, 88.9% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) liveborn singleton babies had a healthy birthweight (between 2,500 grams and 4,449 grams), 9.6% had a low birthweight (less than 2,500 grams), and 1.4% had a high birthweight (4,500 grams or more).

- Babies with a low birthweight are more likely to experience illness or die in infancy, have poorer development of their mental functioning abilities, and have an increased risk of chronic diseases in adulthood. A high birthweight can also have adverse consequences for both the mother (for example, emergency caesarean section and postpartum haemorrhage, impairment and injury of the newborn) and the baby (for example, hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes in later life). This measure mainly focuses on low birthweight, as it has a substantially higher prevalence among First Nations babies than high birthweight.

- Between 2013 and 2020, there was no significant change in the healthy or low birthweight rates for First Nations liveborn singleton babies.

- In 2020, the proportion of low birthweight among First Nations babies varied from lowest in Major cities (8.3%) to highest in Very remote areas (13.1%), and was higher for those born to mothers living in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas compared with those born to mothers living in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (10.6% compared with 5.5%).

- Smoking during pregnancy is a known risk factor for having a low birthweight baby. Of the First Nations mothers who gave birth to a liveborn singleton baby of low birthweight in 2020, over two-thirds (67%) reported that they smoked at any time during the pregnancy.

- In 2020, over 4 in 10 (43%) First Nations mothers smoked tobacco during their pregnancy. 15.0% of the total liveborn singleton First Nations babies born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy had a low birthweight, compared with 5.7% of the total liveborn singleton First Nations babies born to mothers who did not smoke during pregnancy.

- In 2020, the low birthweight rate among First Nations babies was higher for mothers who were aged under 20 (12.3%) than those in other age groups (8.9% to 9.9%).

- The low birthweight rate was nearly twice as high among First Nations babies born to mothers who were underweight prior to pregnancy (21.7%) than First Nations babies born to mothers who had a normal weight (11.1%).

- Access to appropriate antenatal care services is critical to address the factors associated with low birthweight. In 2020, First Nations mothers who attended 5 or more antenatal visits during pregnancy were less likely to have a low birthweight baby (7.5%), compared to those with 2 to 4 antenatal visits (16.7%) or one antenatal visit (15.7%).

- A study of the geographic access for First Nations women of child‑bearing age (15–44 years) to maternal health services found that poorer access to First Nations specific primary health care services with maternal/antenatal services was associated with higher rates of smoking and low birthweight.

- Approximately one-fifth of First Nations women of child-bearing age lived outside a one-hour drive time from the nearest hospital with a public birthing unit. The lowest levels of access for maternal health services were for First Nations women in Remote and Very remote areas.

- Evidence shows that models of care tailored specifically for First Nations women, such as ‘Birthing in Our Community’, result in quantifiable improvements in antenatal care attendance, pre-term births, birth outcomes, perinatal mortality, and breastfeeding practice. These models include culturally appropriate and safe care as well as continuity of care, collaboration between midwives and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers, and involvement of family members such as grandmothers.

Why is it important?

Birthweight is a key indicator of infant health and a principal determinant of a baby’s chance of survival and good health. A normal birthweight (newborns weighing 2,500 grams to less than 4,500 grams; also referred to as ‘healthy birthweight’) helps to lay the foundations for lifelong health. Most Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (First Nations) babies are born with a normal birthweight, but the low birthweight rate among First Nations people remains relatively high compared with non-Indigenous babies.

Women who are healthy before and during pregnancy have a better chance of having a healthy baby. Providing culturally safe continuity of care and addressing risk factors such as maternal smoking and alcohol consumption during pregnancy (see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy); supporting attendance at antenatal care (see measure 3.01 Antenatal care); addressing maternal nutritional status, illness during pregnancy, pre-existing high blood pressure and diabetes, and socioeconomic disadvantage, can lead to improved outcomes for First Nations women and babies including fewer low birthweight babies and lower perinatal mortality (ABS & AIHW 2008; AIHW 2011; Brown et al. 2016; Eades et al. 2008; Khalidi et al. 2012; Panaretto et al. 2014; Sayers & Powers 1997). The Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Services (ACCHSs) sector plays a significant role in providing comprehensive culturally safe models of family-centred primary health care services for First Nations people, including antenatal programs which have delivered improved outcomes for maternal and child health (Panaretto et al. 2007; Panaretto et al. 2014).

Babies with birthweights outside the normal range are at greater risk of illness, poor development, perinatal death, and poorer health in adulthood. Babies with a low birthweight (<2,500 grams) are more likely to experience illness or die in infancy, have poorer development of their mental functioning abilities, and have an increased risk of chronic diseases in adulthood (WHO 2014). A high birthweight can also have adverse consequences. High birthweight is associated with an increased risk of adverse maternal outcomes such as emergency caesarean section and postpartum haemorrhage, impairment and injury of the newborn, and hypertension, obesity, and type 2 diabetes in later life (Beta et al. 2019; Cartwright et al. 2020; Chiavaroli et al. 2014; Turkmen et al. 2018). As birthweight increases the likelihood of risks to the newborn and the mother increases. Excessive fetal growth is often described as ‘large for gestational age’ (birthweight greater than or equal to the 90th percentile for a given gestational age) or ‘macrosomia’ which implies growth beyond an absolute weight variously defined as either greater than 4,000g or 4,500g regardless of gestational age. However, a universally accepted definition of macrosomia has been difficult to establish (Akanmode & Mahdy 2023; American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020). See Box 1.01.1 for birthweight categories used in this measure.

Diabetes in pregnancy poses multiple risks for mother and baby, including but not limited to macrosomia. A 2015 review showed First Nations mothers experienced higher rates of many known adverse outcomes of diabetes in pregnancy compared with non-Indigenous mothers including: macrosomia, caesarean section, congenital deformities, low birthweight, hypoglycaemia, and neonatal trauma (Duong et al. 2015).

The birthweight outcomes for First Nations babies need to be understood in context. Colonisation and subsequent discriminatory government policies have had a devastating impact on First Nations people and cultures. This history and the ongoing effects of entrenched disadvantage, political exclusion, intergenerational trauma, and institutional racism have fundamentally affected the health risk factors, social determinants of health and wellbeing, and poorer outcomes for First Nations people (AIHW 2022a; Productivity Commission 2022).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has been built around 4 Priority Reforms that have been directly informed by First Nations people. These reforms are central to the National Agreement and will change the way governments work with First Nations people, including through working in partnership and sharing decision making, building the Aboriginal community-controlled sector, transforming government organisations, and improving and sharing access to data and information to enable informed decision making by First Nations communities. The National Agreement has identified the importance of making sure First Nations people enjoy long and healthy lives, and ensuring First Nations children are born healthy and strong. To support these outcomes the National Agreement specifically outlines the following targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress:

- Target 1: Close the Gap in life expectancy within a generation, by 2031, (with infant and child mortality as supporting indicators)

- Target 2: By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies with a healthy birthweight to 91 per cent.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Plan 2021–2031 (the Health Plan), provides a strong overarching policy framework for First Nations health and wellbeing and is the first national health document to address the health targets and priority reforms of the National Agreement.

‘Healthy babies and children (Age range: 0–12)’ is one of the key life course phases focused on in the Health Plan, and two objectives specifically address this age range:

- Objective 4.2. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy babies.

- Objective 4.3. Deliver targeted, needs-based and community-driven activities to support healthy children.

Both the National Agreement and the Health Plan are discussed further in the Implications section of this measure.

Burden of disease

In 2018, infant and congenital conditions contributed 5% of the total disease burden for First Nations people. The leading causes were pre-term and low birthweight complications, accounting for 28% of infant and congenital total burden. The age-standardised rate of burden due to infant and congenital conditions for First Nations people was 2.2 times the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2022b).

Data findings

Data used in this measure are from the National Perinatal Data Collection which includes all births in Australian hospitals, birth centres and the community where gestational age is at least 20 weeks or birthweight is at least 400 grams. See Data sources and quality for additional information on this data collection.

The Findings section of this measure refers mostly to singleton live births. A singleton birth is the birth of one baby during a pregnancy. Multiple births are associated with low birthweight and as a result are generally excluded from analysis on low birthweight (AIHW 2020).

In addition to this measure, see the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework (HPF) feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies for additional statistical analysis on birthweight and factors contributing to it.

In this section, most reporting is based on the Indigenous status of the baby – this information is available from 2013 onwards. Some information is reported based on the Indigenous status of the mother – this information has been available for a longer period (from 2005 onwards), with information of a suitable quality for all states and territories available from 2011.

In 2020, data from the National Perinatal Data Collection show that of 17,508 First Nations liveborn singleton babies:

- Almost 9 in 10 were born with a healthy (normal) birthweight (88.9% or 15,572 babies).

- 9.6% (1,680 babies) were born with a low or a very low birthweight (less than 2,499 grams) – including 1,436 babies (8.2%) with a low birthweight, and 244 (1.4%) with a very low birthweight.

- 1.4% (245 babies) were born with a high birthweight (Table D1.01.14).

Of 264,905 non-Indigenous liveborn singleton babies:

- The majority were born with a healthy (normal) birthweight (94.0% or 249,116 babies).

- 4.7% (12,437 babies) were born with a low or a very low birthweight, including 4.0% (10,679 babies) with a low birthweight and 0.7% (1,758) with a very low birthweight.

- 1.2% (3,239 babies) were born with a high birthweight (Table D1.01.14).

Table 1.01–1: Healthy birthweight, by Indigenous status of baby and Indigenous status of mother, 2020

|

|

Singleton live births Number |

Healthy birthweight Number |

Healthy birthweight % |

|---|---|---|---|

|

First Nations babies |

17,508 | 15,572 | 88.9 |

|

Non-Indigenous babies |

264,905 | 249,116 | 94.0 |

|

Births to First Nations mothers |

13,999 | 12,348 | 88.2 |

Source: Tables D1.01.1 and D1.01.17. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection. The data on babies include all births in Australian hospitals, birth centres and the community where gestational age is at least 20 weeks or birthweight is at least 400 grams.

In 2020, the average birthweight of singleton First Nations babies (3,271 grams, based on the Indigenous status of the baby) was slightly higher than the average birthweight for babies of First Nations mothers (3,255 grams, based on the Indigenous status of the mother). The average birthweight of singleton babies (based on the Indigenous status of the baby) for First Nations babies (3,271 grams) was, however, lower than for non-Indigenous babies (3,367grams) (Table D1.01.5).

Between 2013 and 2020, the proportion of First Nations babies born with a healthy birthweight remained steady (ranged between 88.7% in 2013 and 89.5% in 2019) (Table D1.01.18).

The remainder of this section focuses on low birthweight, given the high low birthweight rate among liveborn singleton First Nations babies (9.6%).

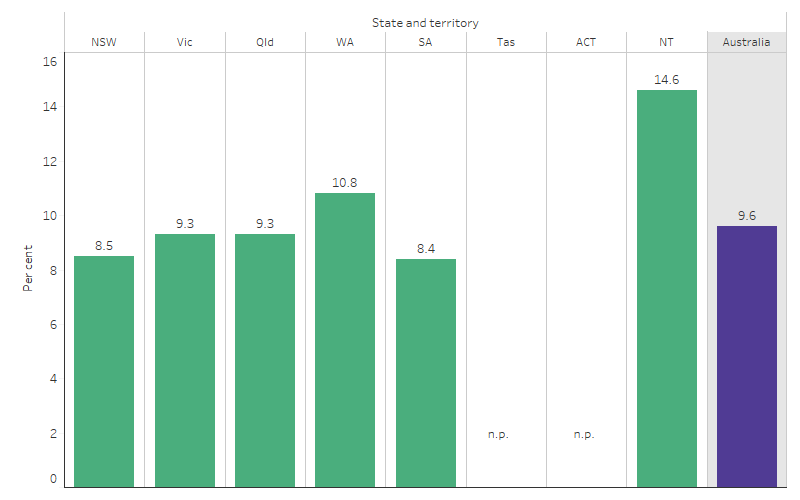

In 2020, the rate of liveborn singleton babies born with a low birthweight varied by jurisdiction:

- For First Nations babies, the low birthweight rate ranged from 8.4% in South Australia to 14.6% in the Northern Territory (Table D1.01.17, Figure 1.01.1).

- For non-Indigenous babies, the rate ranged from 4.5% in New South Wales to 6.2% in Tasmania (Table D1.01.17).

Figure 1.01.1: Low birthweight liveborn singleton First Nations babies, by state and territory, 2020

Source: Table D1.01.17. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

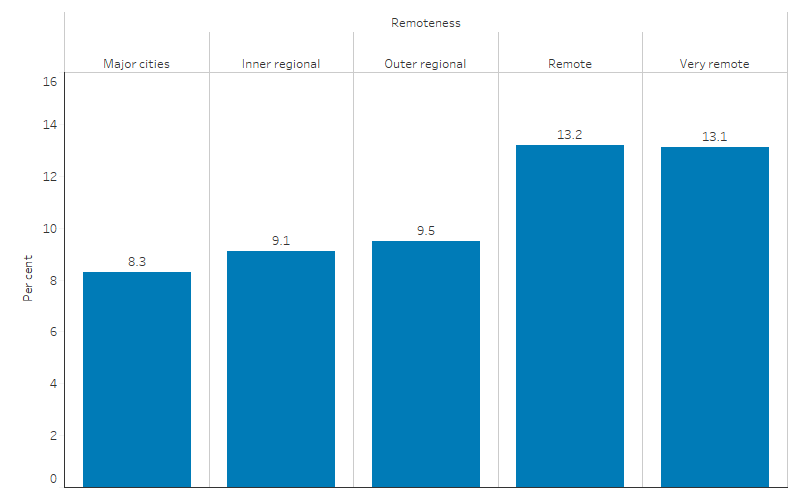

In 2020, the rate of First Nations babies born with a low birthweight varied with remoteness area and was lowest in Major cities (8.3% or 559 babies). When compared with Major cities, rates were higher for those living in Outer regional (9.5% or 334 babies), Remote (13.2% or 157 babies) and Very remote (13.1% or 211 babies) areas. There was no statistically significant difference in rates between Major cities and Inner regional areas (9.1% or 398 babies) (Table D1.01.22; Figure 1.01.2).

Among non-Indigenous babies, the low birthweight rate was similar across jurisdictions, ranging from 4.5% in Outer regional areas to 4.9% in Remote areas (Table D1.01.22).

Figure 1.01.2: Low birthweight liveborn singleton First Nations babies, by remoteness, 2020

Source: Table D1.01.22. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Babies born pre-term with low birthweight

Low birthweight is closely associated with pre-term births (gestational age before 37 completed weeks) (AIHW 2020). The analysis of pre-term birth and low birthweight in this section excludes data on multiple births, stillbirths and births with an unknown gestational age.

In 2020, most First Nations singleton liveborn babies were born full-term (89.6% or 15,691), while 10.4% (1,815 babies) were born pre-term (excludes multiple births). For non-Indigenous babies, 94.3% (249,750 babies) were born full-term, while 5.7% (15,093 babies) were born pre-term (Table D1.01.22).

Among the 1,815 First Nations babies born pre-term in 2020, 58% (1,048 babies) had a low birthweight. For non-Indigenous babies, of the 15,093 born pre-term, 51% (7,659 babies) had a low birthweight (Table D1.01.22).

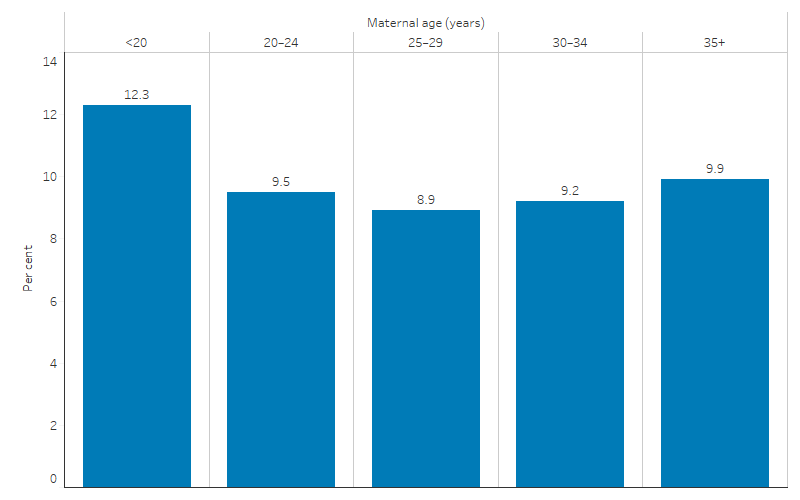

Maternal age and low birthweight

In 2020, the low birthweight rate among First Nations babies was highest for those whose mothers were aged under 20 (12.3% or 235 babies), followed by those aged 35 and over (9.9% or 191 babies), and was lowest for those aged 25–29 (8.9% or 455 babies) (Table D1.01.22, Figure 1.01.3).

Figure 1.01.3: Low birthweight liveborn singleton First Nations babies, by maternal age, 2020

Source: Table D1.01.22. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

For non-Indigenous babies, a higher rate of low birthweight was observed among those whose mothers were aged under 20 and 20–24 (7.7% and 5.8%, respectively) than in other age groups (between 4.3% and 5.1%). Babies born to non-Indigenous mothers in these 2 age groups also had a lower rate of healthy birthweight compared with babies born to mothers of other age groups (Table D1.01.22).

Smoking and low birthweight

Maternal smoking and birth outcomes such as low birthweight and pre-term birth are key drivers of change in infant and child mortality.

Around 4 in 10 First Nations mothers who gave birth in 2020 smoked tobacco during pregnancy (43% or 6,153 mothers). After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, First Nations mothers were 3.8 times as likely to smoke during pregnancy as non-Indigenous mothers (around 44% and 11%, respectively) (Table D2.21.20). Of the 1,411 First Nations mothers who gave birth to a liveborn singleton baby of low birthweight in 2020, over two-thirds (67% or 944 mothers) reported that they smoked at any time during the pregnancy (Table D1.01.7).

In 2020, 15.0% (1,048 babies) of First Nations babies born to a mother who smoked during pregnancy had a low birthweight, compared with 5.7% (591 babies) of First Nations babies born to a mother who did not smoke during pregnancy. First Nations babies born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy were 1.5 times as likely to have a low birthweight as non-Indigenous babies born to mothers who smoked during pregnancy (15.0% and 9.9%, respectively) (Table D1.01.22).

For more information on smoking and low birthweight see Closing the Gap Targets: 2017 Analysis of Progress and Key Drivers of Change.

Antenatal care and low birthweight

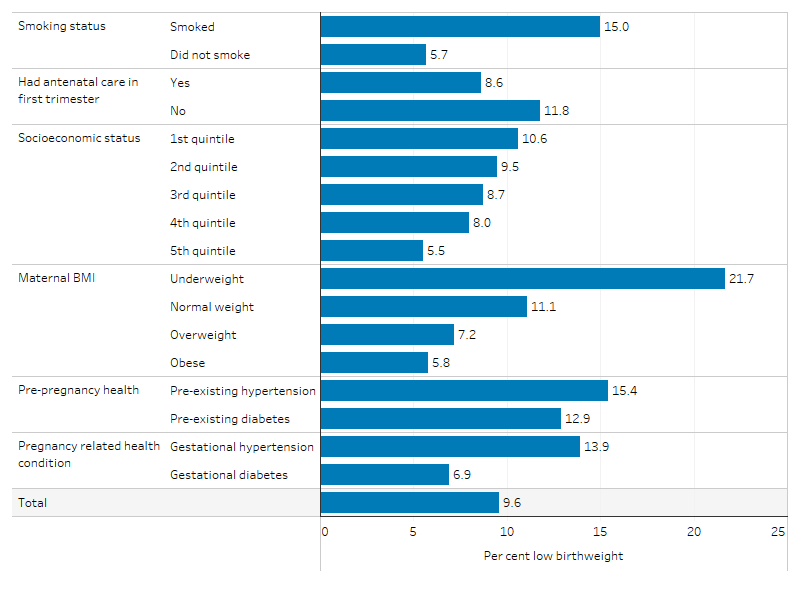

Data from the National Perinatal Data Collection for 2020 showed that First Nations liveborn singleton babies whose mothers attended antenatal care in the first trimester of pregnancy (before 14 weeks) were less likely to have a low birthweight (8.6% or 1,070) compared with First Nations babies whose mothers attended antenatal care after the first trimester or not at all (11.8% or 568) (Table D1.01.22, Figure 1.01.4).

Data by Indigenous status of the mother showed the same pattern. First Nations mothers who attended antenatal care in the first trimester were less likely to have a low birthweight baby than First Nations mothers who attended after 20 or more weeks or not at all to have a low birthweight baby (9.2% compared with 14.0%) (Table D3.01.14).

Of 13,598 First Nations mothers who gave birth at 32 weeks or more gestation with known number of antenatal visits in 2020, 88% (12,023 mothers) had attended 5 or more antenatal visits, 9.3% (1,270 mothers) had attended 2 to 4 antenatal visits, 1.5% (210 mothers) had attended one antenatal visit and 0.7% (95 mothers) attended none of the antenatal visits at any time during their pregnancy. First Nations mothers who attended 5 or more antenatal visits were significantly less likely to give birth to a low birthweight singleton baby (7.5% or 904 of 12,023 mothers), compared with those who had attended 2 to 4 antenatal visits (16.7% or 212 of 1,270 mothers), one antenatal visit (15.7% or 33 of 210 mothers), or who attended no antenatal visits at any time during their pregnancy (16.8% or 16 of 95 mothers) (Table D3.01.5).

Of the 95 First Nations mothers who attended no antenatal visits, one-quarter (25.3% or 24 mothers) gave birth between 32 and 37 weeks of gestation (Table D3.01.6). That is, the period in which the majority of all pre-term births occur (AIHW 2023b).

Low birthweight and other selected characteristics

In 2020, 9.6% (1,680) of all First Nations liveborn singleton babies had a low birthweight. The low birthweight rate was higher among First Nations babies whose mothers:

- lived in the most disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (10.6% or 767 babies), compared with First Nations babies whose mothers lived in the least disadvantaged socioeconomic areas (5.5% or 41 babies) (see Box 1.01.2 for definitions)

- were underweight prior to pregnancy (21.7% or 226 babies), compared with those born to mothers who were a normal weight (11.1%), overweight (7.2%) or obese (5.8%)

- had pre-existing hypertension (15.4% or 26 babies) and pre-existing diabetes (12.9% or 46 babies) (Table D1.01.22, Figure 1.01.4).

Figure 1.01.4: Low birthweight rate among liveborn singleton First Nations babies, by selected maternal characteristics, 2020

Source: Table D1.01.22. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

International birthweight comparisons

For the purposes of presenting comparable results across different countries, this section presents some birthweight results that differ from those presented elsewhere in this measure. Specifically, while most of the results presented elsewhere in this measure relate to liveborn singleton babies (based on the Indigenous status of the baby, the definition used for the Closing the Gap target), the following section presents information for all liveborn babies (including multiple and singleton babies) and information based on the Indigenous status of the mother.

Note that international rate comparisons should be treated with caution because of the differences in methods used to classify and collect data, and the variations in the quality and reliability of the data available in each country. In Australia in 2020, among all live births (including multiple and singleton), 11.2% of First Nations babies were born with low birthweight, compared with 6.2% of other Australians babies. In New Zealand, 7.4% of Māori babies were born with low birthweight, compared with 6.0% of other New Zealander babies (Table D1.01.10).

In Australia in 2020, based on the Indigenous status of the mother, 12.0% of babies born to First Nations mothers had a low birthweight compared with 6.2% of babies born to other Australian mothers. In Canada over the period 2009–2013, 7.2% of mothers from Inuit inhabited regions had babies of low birthweight compared with 6.1% of all mothers. In 2020, the proportion of low birthweight babies among American Indian or Alaska Native mothers was comparable to Other American mothers (7.9% compared with 8.2%) (Table D1.01.10).

Changes over time

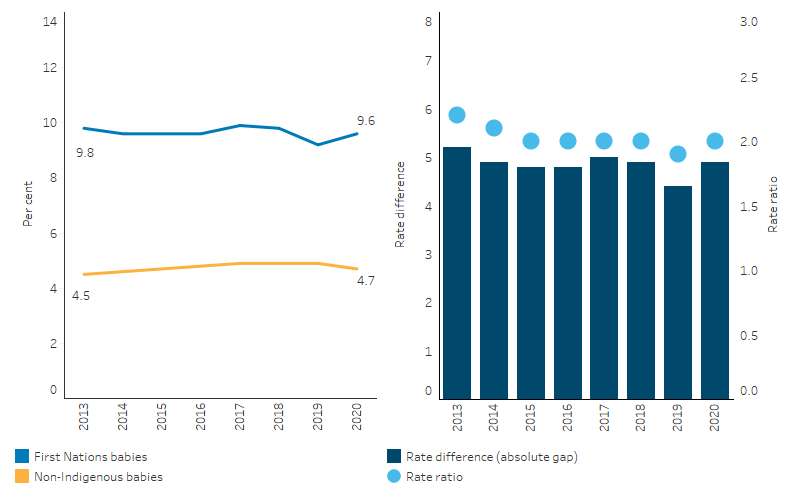

Over the period from 2013 to 2020, the low birthweight rate for First Nations babies did not change significantly (from 9.8% to 9.6%), nor did the rate for non-Indigenous babies (from 4.5% to 4.7%).

The absolute gap in the low birthweight rates between First Nations and non-Indigenous babies ranged between 4.4 percentage points (in 2019) and 5.2 percentage points (in 2013). In 2013, the relative gap was 2.2 times as high for First Nations babies compared with non-Indigenous babies, while in 2020 this was 2.0 times as high for First Nations babies (Table D1.01.20, Figure 1.01.5).

Figure 1.01.5: Proportion of low birthweight liveborn singleton babies and changes in the gap, by Indigenous status of the baby, Australia, 2013 to 2020

Source: Table D1.01.20. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

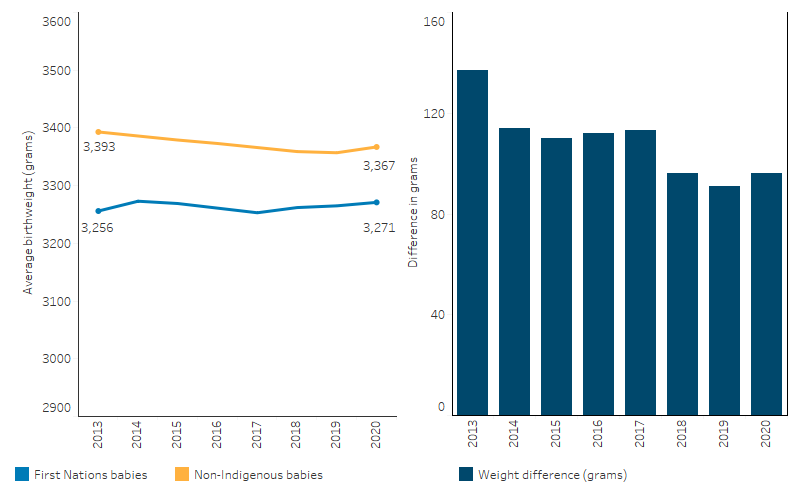

Between 2013 and 2020, the average birthweight of First Nations babies increased slightly (by 0.5%, from 3,256 grams in 2013 to 3,271 grams in 2020, based on singleton live births and Indigenous status of babies), while the average birthweight for non-Indigenous babies decreased slightly over the same period (by 0.8%, from 3,393 gram to 3,367 gram). As a result, the absolute difference in average birthweight between First Nations and non-Indigenous babies decreased from a difference of 137 grams in 2013 to a difference of 96 grams in 2020 (Table D1.01.5, Figure 1.01.6).

Figure 1.01.6: Average birthweight of liveborn singleton babies, by Indigenous status of the baby, Australia, 2013 to 2020

Note: Difference is the average (mean) birthweight of non-Indigenous babies minus the average (mean) birthweight of First Nations babies.

Source: Table D1.01.5. AIHW analysis of the National Perinatal Data Collection.

Research and evaluation findings

Risk of low birthweight

Babies born with low birthweight have been found to experience lifelong and broad-ranging health complications. Studies have identified that low birthweight is associated with:

- greater risks of serious health problems, including pulmonary hypertension, cerebral palsy, intellectual impairment, chronic lung disease, and vision and hearing loss (Howson et al. 2012; Hoy & Nicol 2010)

- increased risk of a range of chronic diseases in adulthood such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and kidney disease (Arnold et al. 2016; Hovi et al. 2007; Hoy & Nicol 2010; Phillips 2006; Tappy 2006; White et al. 2010).

Children who had an extremely low birthweight (less than 1,000 grams) are more likely to face psychosocial problems and difficulties at school. It has been found that teenagers who had extremely low birthweight are less likely to do well at school and experience lower achievement on intellectual measures, particularly arithmetic (AIHW 2011).

A complex range of maternal health and social and demographic factors can contribute to low birthweight.

Based on a multivariate analysis of singleton births for the period 2018–2020, smoking during pregnancy had the largest effect on birthweight (based on adjusted odds ratios) among other maternal characteristics included in the model. When accounting for the prevalence of mothers who smoked, an estimated 38% of low birthweight in First Nations babies was attributable to smoking during pregnancy. If the smoking rate among mothers of First Nations babies was the same as that among mothers of non-Indigenous babies, the proportion of low birthweight First Nations babies could be reduced by 29% (see measure 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy) (Table D1.01.8).

The Western Australian (WA) pre-term birth prevention initiative includes a whole-of-state singleton pregnancy cohort study showing the need to embrace alternative models of care for First Nations women. This initiative, launched in 2014, aimed to reduce pre-term birth rates across the entire population of the state. The study analysed singleton births in WA from 2009 to 2019. Results showed that, among non-Indigenous women, there was an initial reduction in pre-term birth rates across the state, which eventually returned to pre-initiative levels. In contrast, among First Nations women, there was a small reduction in pre-term birth rates in the first 3 years of the initiative, followed by a rise in pre-term birth rates in recent years. The study concluded that the interventions were effective in reducing pre-term birth rates among non-Indigenous women, but were of limited use for First Nations women. It further suggests that future efforts should focus on strategies more likely to be successful for First Nations women, such as midwifery continuity of care models and increased First Nations people’s representation in the healthcare workforce (Berman et al. 2023). This again points to the strength of the ACCHS sector in delivering maternal and child health services that are culturally safe, family-centred, and tailored for First Nations mothers, including the sector’s role in training and employing First Nations health professionals (Panaretto et al. 2014).

Maternal exposure to domestic violence has been found to be associated with significantly increased risk of low birthweight and pre-term birth (Coker et al. 2004; Shah & Shah 2010; Webster 2016). In Australia, First Nations women face a significantly higher risk of violence, particularly domestic violence, compared with non-Indigenous women. Between July 2017 and June 2019, First Nations females were 27 times as likely to be hospitalised for assault as non-Indigenous females. This disparity was most pronounced in remote areas, where First Nations females were 51 times as likely to be hospitalised due to assault as non-Indigenous females living in the same region. For hospitalisations of First Nations females due to assault where the perpetrator was specified, the recorded perpetrator was a domestic partner in 62.3% of cases, and another family member or parent in one-quarter of cases (23.5%) (see measure 2.10 Community safety). These statistics underscore the need for targeted interventions to address domestic violence, as part of broader efforts to ensure the safety and wellbeing of First Nations women and their families.

Other maternal health factors that contribute to low birthweight include excessive alcohol consumption during pregnancy, nutritional status, harmful substance use, low or high body mass index, and maternal age (Howson et al. 2012; Kildea et al. 2017; Kramer et al. 2001; Moutquin 2003; Poulsen et al. 2015).

See the HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies for more detailed analysis of smoking and other factors contributing to birthweight.

A study of the geographic access to maternal health services for First Nations women of child‑bearing age (15–44 years) found that poorer access to First Nations specific primary health care services with maternal/antenatal services was associated with higher rates of smoking and low birthweight. The study found that approximately one-fifth of First Nations women of child-bearing age lived outside a one-hour drive time from the nearest hospital with a public birthing unit. The lowest levels of access for maternal health services were for First Nations women in Remote and very remote areas, compared with other areas (AIHW 2017).

Maternal mental health disorders have been associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as low birthweight and pre-term birth in the literature. A retrospective cohort study using data linkage (N=38,592) using all Western Australian singleton First Nations births (1990–2015) found around 19% of births were to women with at least one mental health disorder reported in the 5 years preceding birth. The study found that compared with not having a mental health disorder, having a disorder in the 5 years before giving birth was associated with adverse perinatal outcomes such as pre-term birth (risk ratio 1.48) and low birthweight (risk ratio 1.81), after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and pre-existing medical conditions. The size of the associations did not vary considerably when examined by type of mental health disorder. The authors argued that prevention and early identification of First Nations women with mental health disorders using culturally validated tools, provision of holistic antenatal care, and provision of culturally safe mental health treatment and support, may improve adverse perinatal and later life outcomes (Adane et al. 2023).

Diabetes in pregnancy and birthweight

Since colonisation, the lifestyle of First Nations people has undergone a rapid transition towards Western lifestyles over a relatively short period of time, and the prevalence of overweight/obesity has become high. In a retrospective cohort study using data linkage of all singleton births in Western Australia (using the Western Australian Data Linkage System), obesity had a stronger association with gestational diabetes in First Nations mothers compared to non-Indigenous mothers. The international literature has shown that gestational diabetes mellitus is the most common complication in pregnancy, and increases the risk of fetal overgrowth, respiratory distress syndrome, neonatal hypoglycaemia, pre-term birth, hyperbilirubinemia and polyhydramnios. Moreover, gestational diabetes has negative long-term implications for both the child and mother. In Australia, gestational diabetes mellitus prevalence is consistently higher among First Nations women. First Nations mothers were also more likely to: be younger, have higher parity, have smoked during pregnancy and live in remote/very remote areas. The likelihood of gestational hypertension, eclampsia/pre-eclampsia and adverse obstetric history events (such as previous events of: Large for Gestational Age (LGA), macrosomia, stillbirth and birth defects) were higher in First Nations mothers than in non-Indigenous mothers. Maternal obesity significantly increases the risk of pregnancy complications among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2023).

In a related study in Western Australia by the same authors, analysis was conducted on the impact of diabetes in pregnancy on trends for births that were LGA. The study found that between 1998 and 2015 the age-standardised rates of pre-gestational diabetes among First Nations mothers rose from 4.3% in 1998 to 5.4% in 2015 but remained below 1% among non-Indigenous women. Over the same period, rates of gestational diabetes rose from 6.7% to 11.5% for First Nations women, and from 3.5% to 10.2% for non-Indigenous women. Analysis highlighted that diabetes in pregnancy substantially contributed to increasing trends in LGA among the First Nations population (Ahmed et al. 2022).

A systematic review of neonatal and pregnancy outcomes of First Nations mothers with diabetes in pregnancy identified that First Nations mothers and babies experienced higher rates of many known adverse outcomes of diabetes in pregnancy than non-Indigenous Australians including: macrosomia, caesarean section, congenital deformities, low birthweight, hypoglycaemia, and neonatal trauma (Duong et al. 2015).

Programs to improve birth outcomes

The literature suggests that one way to improve outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies is through improved access to, and take up of, antenatal care services. Many Australian government- funded antenatal care programs led by ACCHS for First Nations women have been shown to have a quantifiable impact on maternal smoking and alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal nutrition and breastfeeding practices, and that this, in turn, can reduce the low birthweight rate, pre-term birth, and child mortality (AIHW 2014).

Since late 1999, health service providers in Townsville, North Queensland, have worked closely with the First Nations community to improve antenatal services. This collaboration has resulted in an integrated model of shared antenatal care, the Mums and Babies program, delivered from the Townsville Aboriginal and Islanders Health Service. The evaluation of the Mums and Babies program showed that sustained access to a community-based, integrated, shared antenatal services have increased access to antenatal care and improved perinatal outcomes including a reduction in pre-term births and perinatal mortality and an increase in mean birthweight (Panaretto et al. 2007).

A suite of evaluations have been published across Australia on programs to improve the delivery of antenatal services to First Nations women with the intent of improving birth outcomes. The Clinical Practice Guidelines – Pregnancy Care (2020 edition), outlines evidence of successful models of care from these evaluations specifically tailored for First Nations women. This includes culturally appropriate and safe care as well as continuity of care; collaboration between midwives and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health workers; and the role of family members such as grandmothers in attending antenatal care sessions and positively influencing maternal healthy lifestyle behaviours during pregnancy (Department of Health 2020).

The Indigenous Birthing in an Urban Setting study (IBUS) was undertaken to study the effects of ‘Birthing on Country’ service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations people in Queensland. Research from the study focused on the clinical effectiveness of the ‘Birthing in Our Community (BiOC)’ service, a partnership between the Institute for Urban Indigenous Health, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community Health Service Brisbane, and the Mater Mothers’ Hospital. A total of 1,422 women were included in the analysis who received either standard care (656 participants) or the BiOC service (766 participants) between 1 January 2013, and 30 June 2019. The results showed that women engaged with the BiOC service were more likely to attend 5 or more antenatal care visits, had a reduced likelihood of pre-term birth, and were more likely to exclusively breastfeed upon hospital discharge. However, there was no significant difference in smoking rates after 20 weeks of gestation. For the women engaged with the BiOC service, there were also differences in labour care outcomes (such as fewer epidurals in the first stage of labour, fewer planned caesarean sections, being less likely to be admitted to a special neonatal care nursery or neonatal intensive care unit, and more likely to have their third stage of labour managed without intervention) compared with those receiving standard care. The study concluded that the BiOC service, grounded in Birthing on Country principles, has demonstrated clinical effectiveness and resulted in significantly improved maternal and infant outcomes (Kildea S et al. 2021).

The BiOC service offers a cost-effective alternative to Standard Care in reducing the proportion of pre-term births and cost savings per mother-baby pair. The cost savings were driven by less interventions and procedures in birth and fewer neonatal admissions. Investing in comprehensive, community-led models of care improves maternal and child health outcomes at reduced cost (Gao et al. 2023).

The Building On Our Strengths (BOOSt) prospective mixed-methods birth cohort study aims to facilitate and assess the expansion of ‘Birthing on Country’ services into two settings – urban Queensland and rural New South Wales. These services are designed to be community-based and governed, allowing for the incorporation of traditional practices and a connection with land and country. The services offer integrated, holistic care, including continuity of care from primary through to tertiary services, and in safe and supportive spaces. Once published, the analysis will measure the feasibility, acceptability, clinical and cultural safety, effectiveness and cost of the services (Haora et al. 2023).

Many First Nations women do not have access to these specific programs and rely on mainstream health services such as general practitioners and hospital clinics, and it is important therefore for all practitioners to be aware of how to optimise care to First Nations women (Clarke & Boyle 2014). As such, the Clinical Practice Guidelines also urge the importance for mainstream services to embed cultural safety into continuous quality improvement activities for services. Cultural safety is a concept that extends beyond mere recognition and understanding of cultural differences, aiming to foster an environment where individuals, particularly those from marginalised groups such as First Nations people, can feel safe and respected (Evolve Communities 2023). Cultural safety emphasises the experience of the individual receiving care, education, or services. It is rooted in the principle of creating socially and emotionally safe spaces, where people feel their cultural identity is acknowledged and valued. Cultural safety is a commitment to addressing power imbalances and institutional discrimination, ensuring that services and interactions are free from racism and bias, thereby allowing individuals to feel safe and respected in various aspects of their lives.

The evaluation of the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program (ANFPP) found that the program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy, growth, and empowerment. Three main themes were generated: 1) sustaining connections and relationships; 2) developing self-belief and personal skills; and 3) achieving transformation and growth. When the program facilitates the development of culturally safe relationships with staff and peers, it enables behaviour change, skill development, personal goal setting and achievement, leading to self-efficacy. Located within a community-controlled health service, the program can foster cultural connection, peer support and access to health and social services; all contributing to self-efficacy (Massi et al. 2023). However, although the ANFPP has strengths, the impact on low birthweight or smoking during pregnancy among participant mothers was not evident between 2017–18 and 2020–21 (ANFPP Support Service 2021).

Implications

The association between low birthweight and chronic disease in adult life suggests improvements in the rate of low birthweight are essential for improving health outcomes well into the future. The rate of low birthweight among First Nations babies has not changed significantly since 2013, despite an intensified focus on reducing smoking during pregnancy and increasing early and regular access to antenatal care. The HPF feature article Key factors contributing to low birthweight among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies presents more detailed statistical analysis on low birthweight including trend analysis of gestational age (pre-term, early-term, full-term births), birthweight and key contributing factors such as maternal health, smoking during pregnancy and antenatal care attendance. It also provides analysis of the level of improvement required in smoking rates to meet the birthweight target in the National Agreement.

The multivariate analysis of perinatal data suggests that large improvements will result from lowering the rate of smoking during pregnancy. The inclusion of alcohol consumption during pregnancy is a useful addition to the National Perinatal Data Collection, from 2019, that will aid the analysis of maternal risks and birth outcomes in coming years.

Perinatal data indicate that the earlier an expectant mother first accesses antenatal care, the lower the likelihood of having a baby with low birthweight (see measure 3.01 Antenatal care). There is a need for early, high quality, culturally responsive, and women‑centred care delivered for First Nations women in Major cities, Regional and Remote areas (Barclay et al. 2014; Sivertsen et al. 2020). A recent systematic review focused on efforts aimed at improving the delivery of effective health services for First Nations women, including antenatal care, and found improved outcomes when services were designed specifically for and with First Nations women. This finding supports the important role of ACCHSs in the design and delivery of services.

The Australian Government has allocated funding from 2021–22 to 2024–25 to extend the ANFPP at 13 existing locations and introduce it to 2 new areas in Western Australia. The ANFPP, tailored for First Nations communities, offers home visits by nurses to women expecting a First Nations child, supporting them from pregnancy until the child is 2 years old. It also funds several initiatives to enhance antenatal care and health behaviours for First Nations women during pregnancy, including: 'Baby coming you ready; National Pre-term Birth Prevention Program; and the Women-centred care strategy'.

Australian governments are investing in a range of initiatives aimed at improving child and maternal health. Descriptions are included in the Policies and Strategies section and include the Connected Beginnings, the National Tobacco Campaign’s Tackling Indigenous Smoking (TIS) program, the iSISTAQUIT program, Australian National Breastfeeding Strategy: 2019 and Beyond, and the National Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) Strategic Action Plan. See also measures 3.01 Antenatal care and 2.21 Health behaviours during pregnancy.

Enhanced primary care services and continued improvement in, and access to, culturally appropriate antenatal care have the capacity to support improvements in the health of the mother and baby. This highlights the important role ACCHSs have in leading culturally safe and responsive health care within their communities (Panaretto et al. 2014). ACCHSs are operated and governed by the local community to deliver holistic, strengths-based, comprehensive and culturally safe primary health care services across urban, regional, rural and remote locations. The Australian Government committed to building a strong and sustainable First Nations community-controlled sector delivering high quality services to meet the needs of First Nations people across the country under Priority Reform Two of the National Agreement on Closing the Gap. Further work to ensure mainstream services can provide culturally safe and responsive care for First Nations people is also critically important and relates to Priority Reform Three of the National Agreement. These 2 dimensions of health care for First Nations people have been emphasised in the Health Plan which places culture at the foundation for First Nations health and wellbeing as a protective factor across the life course.

The Health Plan, released in December 2021, is the overarching policy framework to drive progress against the Closing the Gap Priority Reforms and health targets. Implementation of the Health Plan aims to drive structural reform towards models of care that are prevention and early intervention focused, with greater integration of care systems and pathways across primary, secondary and tertiary care. It also emphasises the need for mainstream services to address racism and provide culturally safe and responsive care, and be accountable to First Nations people and communities.

The Health Plan suggests that efforts should be targeted at providing strengths-based, culturally safe and holistic, affordable services to ensure a strong start to life. Comprehensive, wrap-around, community-led Birthing on Country services have the potential to support healthy pregnancies by offering an integrated, holistic and culturally safe model of care (Department of Health 2021).

Research has shown that Birthing on Country (BoC) models of care, which offer culturally safe, continuous midwifery care for First Nations women, improve birth outcomes for First Nations mothers and babies (such as improving frequency of antenatal care visits and reducing the likelihood of pre-term birth). The Australian Government is actively promoting the BoC model, especially in rural and remote areas where birthing outcomes can be challenging. To support this, the Australian Government has committed $32.2 million over 4 years (2021–22 to 2024–25) under the Healthy Mums, Healthy Bubs initiative to enhance the maternity health workforce and BoC practices. Additional funding ($22.5 million) has also been allocated over 3 financial years (2022–23 to 2024–25) for the establishment of a BoC Centre of Excellence at Waminda in Nowra, New South Wales. The Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) also funded The Birthing on Country: RISE SAFELY study with $5 million, which will establish exemplar BoC services in 3 rural, remote and very remote settings. The study is First Nations led, co-designed and staffed. More broadly, the Department of Health and Aged Care is partnering with the National Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (NACCHO) to develop a maternal and child health model of care to enable First Nations mothers and families to access consistent, culturally safe and effective care (NIAA 2023).

As part of the National Agreement, the health sector was identified as one of 4 initial sectors for joint national strengthening effort and the development of a 3-year Sector Strengthening Plan. The Health Sector Strengthening Plan (Health-SSP) was developed in 2021, to acknowledge and respond to the scope of key challenges for the sector, providing 17 transformative sector strengthening actions. Developed through strong consultation across the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community-controlled health sector and other First Nations health organisations, the Health-SSP will be used to prioritise, partner and negotiate beneficial sector-strengthening strategies.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2018. Census of Population and Housing: Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA), Australia, 2016. Cat. no. 2033.0.55.001. Canberra: ABS.

- ABS & AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2008. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2008. Canberra: ABS & AIHW.

- Adane A, Shepherd C, Walker R, Bailey H, Galbally M & Marriott R 2023. Perinatal outcomes of Aboriginal women with mental health disorders. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57.

- Ahmed M, Bailey H, Pereira G, White S, Hare M, Wong K et al. 2023. Overweight/obesity and other predictors of gestational diabetes among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal women in Western Australia. Preventive Medicine Reports 36:102444.

- Ahmed M, Bailey H, Pereira G, White S, Wong K & Shepherd C 2022. Trends and burden of diabetes in pregnancy among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal mothers in Western Australia, 1998–2015. BMC Public Health 22:263.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2011. Headline indicators for children's health, development and wellbeing 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2014. Timing impact assessment of COAG Closing the Gap targets: Child mortality. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017. Spatial variation in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women's access to 4 types of maternal health services. Canberra AIHW.

- AIHW 2020. Australia’s mothers and babies 2018: in brief. Perinatal statistics series no. 36. Cat. no. PER 108. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022a. Determinants of health for Indigenous Australians. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2022b. Australian Burden of Disease Study: Impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2018. Canberra: AIHW, Australian Government.

- AIHW 2023a. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and babies. Canberra.

- AIHW 2023b. Australia's mothers and babies. Canberra: AIHW.

- Akanmode AM & Mahdy H 2023. Macrosomia. StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020. Macrosomia: ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 216. Obstetrics & Gynecology 135:e18-e35.

- ANFPP (Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program) Support Service 2021. National Annual Data Report 1 July 2020 - 30 June 2021. Brisbane.

- Arnold L, Hoy W & Wang Z 2016. Low birthweight increases risk for cardiovascular disease hospitalisations in a remote Indigenous Australian community – a prospective cohort study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 40:S102-S6.

- Barclay L, Kruske S, Bar-Zeev S, Steenkamp M, Josif C, Narjic CW et al. 2014. Improving Aboriginal maternal and infant health services in the ‘Top End’ of Australia; synthesis of the findings of a health services research program aimed at engaging stakeholders, developing research capacity and embedding change. BMC health services research 14:241.

- Berman YE, Newnham JP, White SW, Brown K & Doherty DA 2023. The Western Australian preterm birth prevention initiative: a whole of state singleton pregnancy cohort study showing the need to embrace alternative models of care for Aboriginal women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23:7.

- Beta J, Khan N, Khalil A, Fiolna M, Ramadan G & Akolekar R 2019. Maternal and neonatal complications of fetal macrosomia: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 54:308-18.

- Brown S, Mensah FK, Ah Kit J, Stuart-Butler D, Glover K, Leane C et al. 2016. Aboriginal Families Study Policy Brief No 4: Improving the health of Aboriginal babies. Melbourne: MCRI.

- Cartwright RD, Anderson NH, Sadler LC, Harding JE, McCowan LM & McKinlay CJ 2020. Neonatal morbidity and small and large size for gestation: a comparison of birthweight centiles. Journal of Perinatology 40:732-42.

- Chiavaroli V, Marcovecchio ML, de Giorgis T, Diesse L, Chiarelli F & Mohn A 2014. Progression of cardio-metabolic risk factors in subjects born small and large for gestational age. PloS one 9:e104278.

- Clarke M & Boyle J 2014. Antenatal care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Australian Family Physician 43:20-4.

- Coker AL, Sanderson M & Dong B 2004. Partner violence during pregnancy and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 18:260-9.

- Department of Health 2020. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pregnancy Care. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health.

- Department of Health 2021. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health plan 2021–2031. Canberra: Australian Government of Department of Health.

- Duong V, Davis B & Falhammar H 2015. Pregnancy and neonatal outcomes in Indigenous Australians with diabetes in pregnancy. World journal of diabetes 6:880.

- Eades S, Read AW, Stanley FJ, Eades FN, McCaullay D & Williamson A 2008. Bibbulung Gnarneep ('solid kid'): causal pathways to poor birth outcomes in an urban Aboriginal birth cohort. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 44:342-6.

- Evolve Communities 2023. What’s the difference between Cultural Competence and Cultural Safety? .

- Gao Y, Roe Y, Hickey S, Chadha A, Kruske S, Nelson C et al. 2023. Birthing on country service compared to standard care for First Nations Australians: a cost-effectiveness analysis from a health system perspective. The Lancet Regional Health Western Pacific.

- Haora P, Yvette R, Hickey S, Gao Y, Nelson C & Allen J et al. 2023. Developing and evaluating Birthing on Country services for First Nations Australians: the Building On Our Strengths (BOOSt) prospective mixed methods birth cohort study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23.

- Hovi P, Anderson S, Eroksson J & Jarvenpaa A 2007. Glucose regulation in young adults with very low birthweight. New England Journal of Medicine 356:2053-63.

- Howson C, Kinney M & Lawn J 2012. The global action report on preterm birth, born too soon. Geneva: March of Dimes, Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health, Save the Children. World Health Organisation.

- Hoy W & Nicol J 2010. Birthweight and natural deaths in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. The Medical Journal of Australia 192:14-9.

- Khalidi N, McGill K, Houweling H, Arnett K & Sheahan A 2012. Closing the Gap in Low Birthweight Births between Indigenous and Non-Indigenous Mothers, Queensland. (ed., Health Statistics Centre, Queensland Health). Brisbane: QLD Health.

- Kildea S, Gao Y, Hickey S, Nelson C, Kruske S & Carson A et al. 2021. Effect of a Birthing on Country service redesign on maternal and neonatal health outcomes for First Nations Australians: a prospective, non-randomised, interventional trial. The Lancet Global Health 9:e651-e9.

- Kildea SV, Gao Y, Rolfe M, Boyle J, Tracy S & Barclay LM 2017. Risk factors for preterm, low birthweight and small for gestational age births among Aboriginal women from remote communities in Northern Australia. Women and Birth 30:398-405.

- Kramer MS, Goulet L, Lydon J, Séguin L, McNamara H, Dassa C et al. 2001. Socio‐economic disparities in preterm birth: causal pathways and mechanisms. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 15:104-23.

- Massi L, Hickey S, Maidment SJ, Roe Y, Kildea S & Kruske S 2023. “This has changed me to be a better mum”: A qualitative study exploring how the Australian Nurse-Family Partnership Program contributes to the development of First Nations women’s self-efficacy. Women and Birth.

- Moutquin J-M 2003. Socio-economic and psychosocial factors in the management and prevention of preterm labour. BJOG: an international journal of obstetrics and gynaecology 110:56-60.

- NIAA (National Indigenous Australians Agency) 2023. Commonwealth Closing the Gap Implementation Plan 2023. Canberra: National Indigenous Australians Agency.

- Panaretto K, Mitchell M, Anderson L, Larkins S, Manessis V, Buettner P et al. 2007. Sustainable antenatal care services in an urban Indigenous community: the Townsville experience. Medical Journal of Australia 187:18-22.

- Panaretto K, Wenitong M, Button S & Ring I 2014. Aboriginal community controlled health services: leading the way in primary care. The Medical Journal of Australia 200:649-52.

- Phillips D 2006. Birth weight and adulthood disease and the controversies. Fetal and Maternal Medicine Review 17:205-27.

- Poulsen G, Strandberg‐Larsen K, Mortensen L, Barros H, Cordier S, Correia S et al. 2015. Exploring Educational Disparities in Risk of Preterm Delivery: A Comparative Study of 12 E uropean Birth Cohorts. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology 29:172-83.

- Productivity Commission 2022. Closing the Gap Annual Data Compilation Report July 2022.

- Sayers S & Powers J 1997. Risk factors for aboriginal low birthweight, intrauterine growth retardation and preterm birth in the Darwin Health Region. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Public Health 21:524-30.

- Shah PS & Shah J 2010. Maternal exposure to domestic violence and pregnancy and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Journal of Women's Health 19:2017-31.

- Sivertsen N, Anikeeva O, Deverix J & Grant J 2020. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family access to continuity of health care services in the first 1000 days of life: a systematic review of the literature. BMC health services research 20.

- Tappy L 2006. Adiposity in children born small for gestational age. International Journal of Obesity 30:36-40.

- Turkmen S, Johansson S & Dahmoun M 2018. Foetal macrosomia and foetal-maternal outcomes at birth. Journal of pregnancy 2018.

- Webster K 2016. A preventable burden: Measuring and addressing the prevalence and health impacts of intimate partner violence in Australian women Australia's National Research Organisation for Women's Safety, Compass.

- White A, Wong W, Sureshkumur P & Singh G 2010. The burden of kidney disease in Indigenous children of Australia and New Zealand, epidemiology, antecedent factors and progression to chronic kidney disease. Journal of Paediatrics & Child Health 46:504-9.

- WHO (World Health Organization) 2014. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low birth weight policy brief. World Health Organization.