Key Messages

- In 2021, 48% (182,620) of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 20–64 had either completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification at any level. This is an increase from 42% in 2016 and 35% in 2011.

- In 2018–19, Indigenous Australians aged 15–64 who had a non-school qualification were more likely to be employed (61%) than those without a non-school qualification (38%).

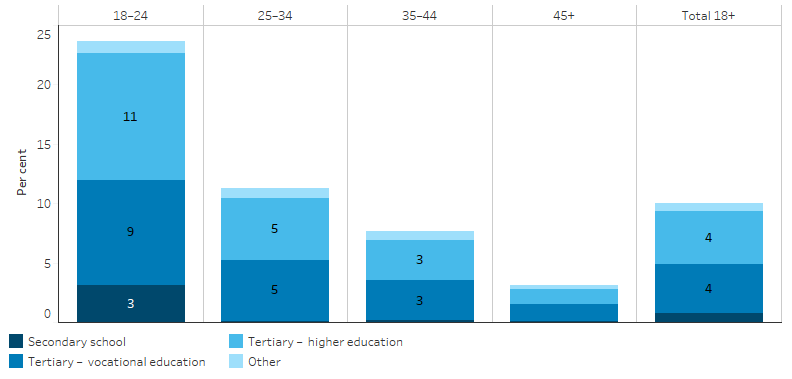

- Of Indigenous Australians aged 18–24, nearly 1 in 4 (24%) were currently studying in 2021 - 11% were attending university or other higher education, 9% were attending vocational education and training, 3% were attending secondary school, and 1% were attending other educational institutions.

- 11% of Indigenous Australians aged 25–34 were currently studying in 2021, as were 8% of those aged 35–44, and 3% of those aged 45 and over.

- The proportion of Indigenous adults currently attending an educational institution decreased with increasing remoteness of usual residence – from 14% in Major cities to 2.8% in Very remote areas. In non-remote areas, 12% of Indigenous adults were currently studying, compared with 3.5% in remote areas.

- In 2018, there were 18,062 Indigenous higher education students, making up 1.8% of the higher education student population.

- The number of Indigenous students commencing in higher education more than doubled, from 3,624 students in 1996 to 7,273 students in 2018. The rate of commencing Indigenous students aged 20–64 increased by 37%, from 148 per 10,000 in 2001 to 170 per 10,000 in 2018.

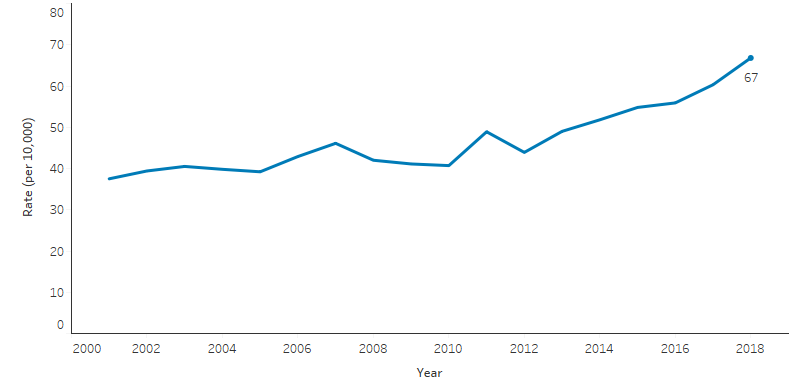

- The rate at which Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 completed higher education courses rose from 38 per 10,000 in 2001 to 67 per 10,000 in 2018, an increase of 68%.

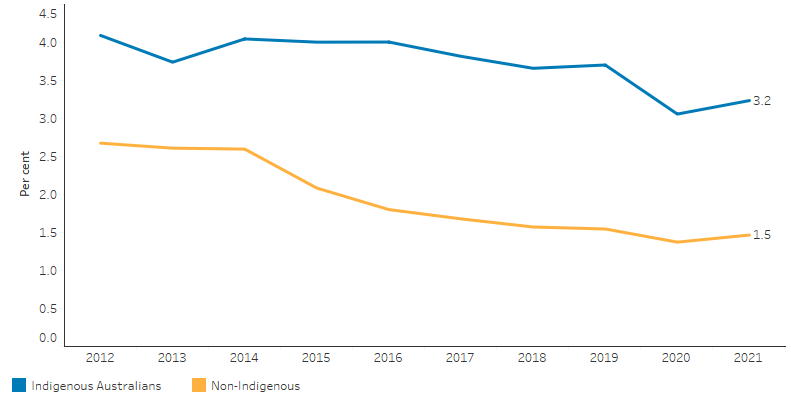

- In the decade from 2012 and 2021, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over completing government funded VET qualifications decreased from 4.1% to 3.2%. The proportion also decreased among non-Indigenous Australians, from 2.7% of those aged 15 and over in 2012, to 1.5% in 2021.

- Looking at non-school qualifications, in 2021, 48% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 reported they either completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification at any level – compared with 71% for non-Indigenous Australians. This gap was due to lower rates of attainment at Bachelor Degree and above, with 10% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 having a Bachelor Degree or above, compared with 35% of non-Indigenous adults.

- Research has found that if Indigenous and non-Indigenous students reach the same level of academic achievement by the time they are 15, there is no significant difference in subsequent educational outcomes, such as completing Year 12 and participating in university or vocational education and training.

- Limited opportunities to participate in higher education on Country requires many Indigenous students wishing to further their education to relocate. A relatively high proportion of Indigenous university students come from regional and remote areas, and housing and relocation costs are often an additional burden. Students who relocate may experience further challenges such as isolation from being away from their families and communities.

- Adult learning can indirectly benefit physical and mental health by improving social capital and connectedness, health behaviour, skills and employment outcomes. There is evidence that participation in adult education can have a greater effect on health and social outcomes for people in more disadvantaged groups. Longitudinal studies show that adults who participate in post-school learning engage in healthier behaviours, including increased amounts of physical exercise, reduced alcohol consumption and smoking cessation, and improved social and emotional wellbeing.

Why is it important?

Education is well recognised as a key determinant of health and continued learning as an adult is regarded as a powerful tool in achieving better health, education and economic outcomes (Chandola & Jenkins 2014). The employment gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians declines as the level of educational attainment increases. A university education will not suit the aspirations of everyone, but pursuing post-school qualifications will increase opportunities for socioeconomic advancement. Indigenous Australians with a post-school qualification have improved likelihood of employment (Boyd 1996). The transition from education to work is usually smoother for VET and university graduates, and salary outcomes are higher than for those who enter the workforce directly from school (Lamb & McKenzie 2001).

Indigenous Australians that have graduated from university and transitioned into professional roles are sending an important signal to future Indigenous Australian graduates by highlighting potential career pathways into professions for which Indigenous Australians have been under-represented. Larger cohorts of Indigenous Australians working in the professions will consequently affect Indigenous Australian participation in the mainstream economy (Anderson 2011).

Health outcomes are also influenced by a person’s ability to use a wide range of materials and resources to build health knowledge and support informed health decision making (ACSQHC 2013). Adult learning can indirectly benefit physical and mental health by improving social capital and connectedness, health behaviour, skills and employment outcomes. Further, there is evidence that participation in adult education can have a greater effect on health and social outcomes for people in more disadvantaged groups (Institute of Health Equity 2014). Longitudinal studies show that adults who participate in post-school learning engage in healthier behaviours, including increased amounts of physical exercise, reduced alcohol consumption and smoking cessation, and have improved social and emotional wellbeing (Schuller 2017). While the benefits of adult learning are well known, there is little evidence to assist with distinguishing ‘cause’ from ‘effect’ with regard to better health and better education (Hart et al. 2017).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap (the National Agreement) was developed in partnership between Australian governments and the Coalition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peak Organisations. The National Agreement has identified the importance of engagement in further education and employment, with specific outcomes and targets to direct policy attention and monitor progress. These include:

- Target 6 — By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25–34 years who have completed a tertiary qualification (Certificate III and above) to 70 per cent.

- Target 7 — By 2031, increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth (15–24) who are in employment, education or training to 67 per cent.

For the latest data on the Closing the Gap targets, see the Closing the Gap Information Repository.

Data findings

Currently attending an educational institution

In the 2021 ABS Census of Population and Housing, 10% of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over reported that they were currently studying at an educational institution (48,246 of 470,973 people whose attendance at an educational institution was stated) (Table D2.06.1).

Among Indigenous Australians aged 18–24, 1 in 4 (24%) were currently studying, decreasing to 11% of those aged 25–34, 8% of those aged 35–44, and 3% of those aged 45 and over (Table D2.06.1).

Among Indigenous Australians aged 18–24, 3.2% (3,044) were in secondary school, 11% (10,314) in tertiary university or other higher education and 8.8% (8,478) in tertiary vocational education (including Technical and Further Education (TAFE) and private training providers) (Table D2.06.1, Figure 2.06.1). About three-quarters (76%) of Indigenous Australians in this age group reported not attending an educational institution.

Figure 2.06.1: Proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over currently attending educational institutions, by type of institution and age group, 2021

Note: In the figure, ‘Other’ includes ‘Tertiary – not further defined’, ‘Other’ and ‘Educational Institution not stated’.

Source: Table D2.06.1. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

The proportion of Indigenous adults who were studying was highest among those living in the Australian Capital Territory, where 19% were currently studying, followed by Victoria at 14% (Table D2.06.3).

The proportion of Indigenous Australians currently attending an educational institution decreased with increasing remoteness of usual residence – from 14% in Major cities to 2.8% in Very remote areas (Table D2.06.4). In non-remote areas combined (Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas), 12% of Indigenous adults were currently studying, compared with 3.5% in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined).

Highest level of school completed

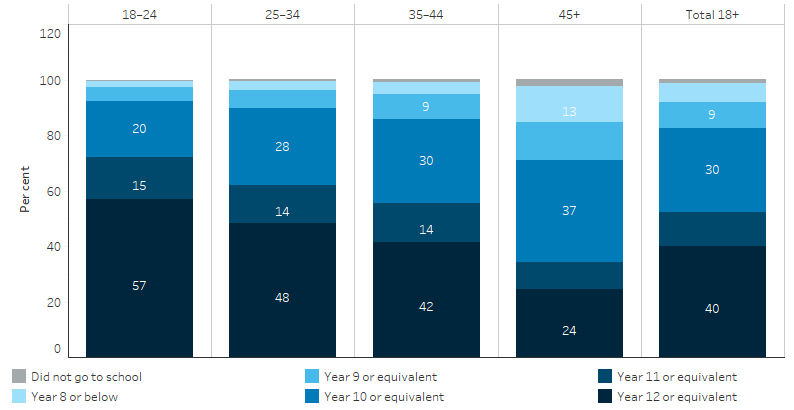

In the 2021 Census, 40% (188,531) of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over reported Year 12 or equivalent as their highest level of school completed (Table D2.06.5). Note that ‘equivalent’ qualifications in the context of these data refers to secondary school-based qualifications or equivalents (for example, Year 13, 6th form, and Higher School Certificate). It excludes non-school qualifications, and therefore differs to the specifications used for the Closing the Gap target on Year 12 or equivalent attainment – see measure 2.05 Education outcomes for young people for those data.

Across age groups, 57% of Indigenous Australians aged 18–24 reported Year 12 or equivalent as their highest level of school completed in the 2021 Census (55,461 of 97,204, excluding those whose highest year of school completed was not stated). This proportion was lower in older age groups – 48% of Indigenous adults aged 25–34 had completed Year 12 or equivalent, compared with 42% of those aged 35–44, and 24% of those aged 45 and over. Among Indigenous Australians aged 18–24, 28% had finished school at Year 10 level or below – this proportion was higher in older age groups, increasing to 66% of those aged 45 and over (Table D2.06.5, Figure 2.06.2).

Figure 2.06.2: Highest level of school completed, Indigenous Australians, by age group, 2021

Source: Table D2.06.5. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

In 2021, among Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over, females were more likely than males to have completed Year 12 or equivalent (42% and 37%, respectively) as their highest level of school completion. The proportion of Indigenous adults who had completed Year 11 as their highest attainment was similar for Indigenous females and males (13% and 12% respectively), while the proportion with Year 10 or below was higher for males than females (51% compared with 45%) (Table D2.06.6).

The Australian Capital Territory had the highest proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over who completed Year 12 or equivalent (60%) and the Northern Territory had the lowest (26%) (Table D2.06.7).

The proportion of Indigenous Australians who had completed Year 12 or equivalent decreased with increasing remoteness, from 47% in Major cities to 27% in Very remote areas (Table D2.06.8). Overall, 42% of Indigenous Australians who lived in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner regional, or Outer regional combined) had completed Year 12 or equivalent, compared with 28% of those in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined).

Non-school qualifications

Non-school qualifications include Certificate I to Certificate IV, Diploma, Bachelor, Master and Doctoral level qualifications. Non-school qualifications can be completed through higher education or Vocational Education and Training (VET).

In the 2021 Census of Population Housing, information was collected on the highest level of non-school qualification among people who had completed a qualification. Information was also collected on whether people were currently studying for a non-school qualification, though not the level of qualification for which they were studying.

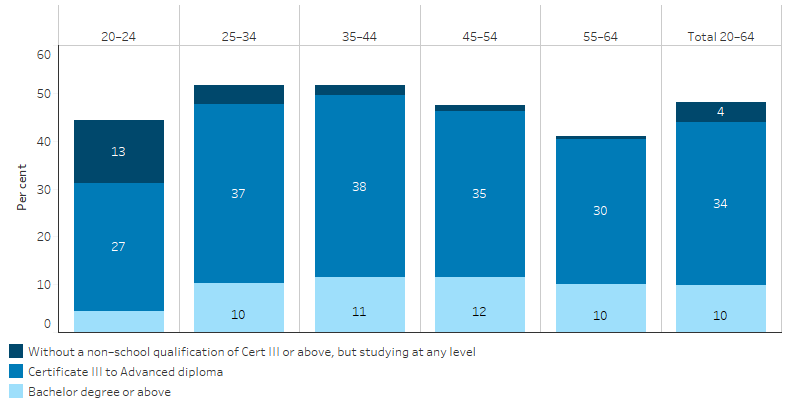

Based on data from the Census of Population and Housing, in 2021:

- 44% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 had completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above (167,004 of 380,593)

- 4% had not completed a qualification at Certificate III or above but were currently studying for a non-school qualification (at any level) (15,609 of 380,593) (Table D2.06.10).

Across age groups in 2021, the proportion of Indigenous adults who had completed a Certificate III or above, or were studying for a non-school qualification (at any level) was highest among those aged 25–34 and 35–44 (both 52%). In 2021, the proportion of Indigenous adults who had completed Bachelor Degree or above was 10%, with this proportion ranging between 10% and 12% across all age groups except younger adults aged 20–24 (4%) (Table D2.06.10, Figure 2.06.3).

Figure 2.06.3: Non–school qualifications at Certificate III level or above and/or currently studying, Indigenous Australians, by age group, 2021

Source: Table D2.06.10. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

The Australian Capital Territory had the highest proportion of Indigenous Australians who completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification (68%) and the Northern Territory had the lowest (23%) (Table D2.06.11).

The proportion of Indigenous Australians who had a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification decreased with increasing remoteness, ranging from 57% in Major cities to 20% in Very remote areas (Table D2.06.12). Overall, about half (53%) of Indigenous Australians who lived in non-remote areas (Major cities, Inner regional and Outer regional areas combined) had a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification, compared with about one-quarter (24%) of those living in remote areas (Remote and Very remote areas combined).

Looking at the level of completed non-school qualifications, in 2021:

- the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 who had completed a Certificate III to Advanced Diploma ranged from 37% in Major cities to 16% in Very remote

- the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 who had completed a Bachelor Degree or above ranged from 14% in Major cities to 2.2% in Very remote areas (Table D2.06.12).

The National Agreement on Closing the Gap includes an outcome to increase the proportion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged 25–34 who have completed a tertiary qualification (Certificate III and above) to 70 per cent. In 2021, 47% of Indigenous Australians aged 25–34 held a non-school qualification of a Certificate III or above, consisting of:

- 1.3% with a Postgraduate Degree

- 1.1% with a Graduate Diploma or Graduate Certificate

- 7.8% with a Bachelor Degree

- 7.4% with an Advanced Diploma or Diploma

- 29.5% with a Certificate III or IV (Productivity Commission 2023).

In this age group, Indigenous females were more likely than Indigenous males to have completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III level or above (51% compared with 43%) (Productivity Commission 2023).

The Australian Capital Territory had the highest proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 25-34 with a non-school qualification at or above Certificate III (65%) and the Northern Territory had the lowest (19%) (Table D2.06.36).

The proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 25-34 with a non-school qualification at or above Certificate III ranged from 57% in Major cities to 17% in Very remote areas (Table D2.06.36).

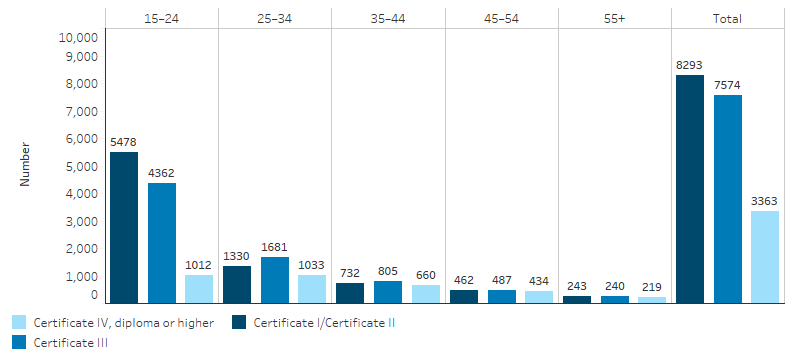

Vocational education and training

In 2021, Indigenous Australians completed 19,230 Vocational Education and Training (VET) sector qualifications – 8,293 at Certificate I/II level (43%), 7,574 at Certificate III level (39%), and 3,363 at Certificate IV level or higher (17%) (Table 2.06.15).

In 2021, 56% of VET completions among Indigenous Australians were for those aged 15–24 (or 10,853). A further 21% of VET completions among Indigenous Australians were for people aged 25–34, 11% were for those aged 35–44 years (2,204), and 11% were for those aged 45 and over (2,092) (Table D2.06.15).

Among Indigenous Australians aged 15–24, VET completions were predominantly at Certificate I/II or Certificate III levels (5,478 and 4,362 completions in 2021 respectively), with a relatively smaller number at Certificate IV level or higher (1,012). In older age groups, Certificate I/II or Certificate III level completions were also more common than completions at Certificate IV or higher, though the differences were smaller (Table D2.06.15, Figure 2.06.4).

In 2021, the number of VET completions at Certificate IV level or higher was highest among Indigenous Australians aged 25–34 (1,033 completions), followed by those aged 15–24 (1,012) (Table D2.06.15, Figure 2.06.4).

Figure 2.06.4: Qualifications completed by Indigenous Australians in the VET sector, by age group, 2021

Note: Total includes qualifications for people aged under 15 and people with unknown age (not shown separately in figure).

Source: Table D2.06.15. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022).

Across jurisdictions, the number of VET qualifications completed among Indigenous Australians in 2021 was highest in Queensland (7,480, or 39% of all VET completions among Indigenous Australians), followed by New South Wales (5,792, or 30%), and Western Australia (2,463, or 13%) (Table D2.06.16).

In 2021, 86% of VET completions among Indigenous Australians were for those who lived in non-remote areas (Table D2.06.31).

Higher education

- there were 18,062 Indigenous higher education students, making up 1.8% of the higher education student population.

- 7,273 Indigenous students commenced a higher education course.

- 2,865 courses were completed by Indigenous students (Table D2.06.24).

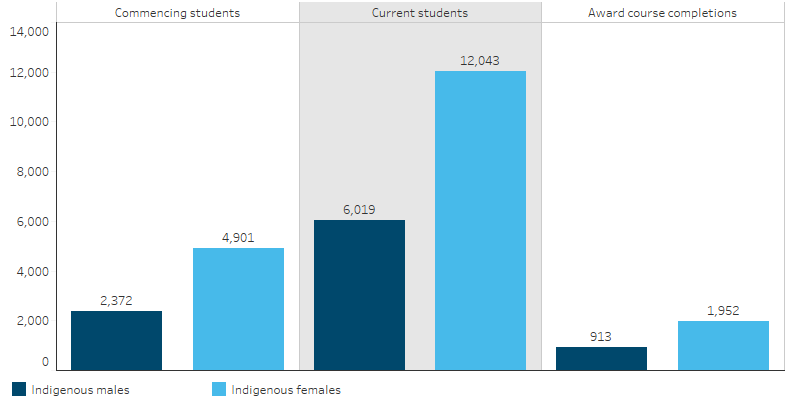

In 2018, there were more Indigenous females engaged in higher education than Indigenous males. Of Indigenous higher education students, twice as many were female (12,043 compared with 6,019 for males). There were twice as many commencing female than male Indigenous students (4,901 compared with 2,372, respectively) (Table D2.06.28, Figure 2.06.5).

Figure 2.06.5: Number of commencing students, current students and course completions, Indigenous higher education students, by sex, 2018

Source: Table D2.06.28. AIHW analysis of Department of Education Higher Education Statistics Collection.

The number of higher education course completions was twice as high for Indigenous females than Indigenous males (1,952 compared with 913, respectively) (Table D2.06.28, Figure 2.06.5). For non-Indigenous higher education students, there were about 1.5 times as many course completions by females (133,262) as by males in 2018 (89,854) (Table D2.06.28).

The top three fields of study for Indigenous students in 2018 were society and culture (34% or 6,172 students), health (23% or 4,169 students) and education (14% or 2,448 students) (Table D2.06.27).

The proportion of Indigenous higher education students who did not complete their course of study was the same in 2005 and 2017. In 2017, the higher education attrition rate for Indigenous students was 35%, up from 31% in 2016. The higher education attrition rate for non-Indigenous students was 23% in 2017, up from 20% in 2005 (Table D2.06.29).

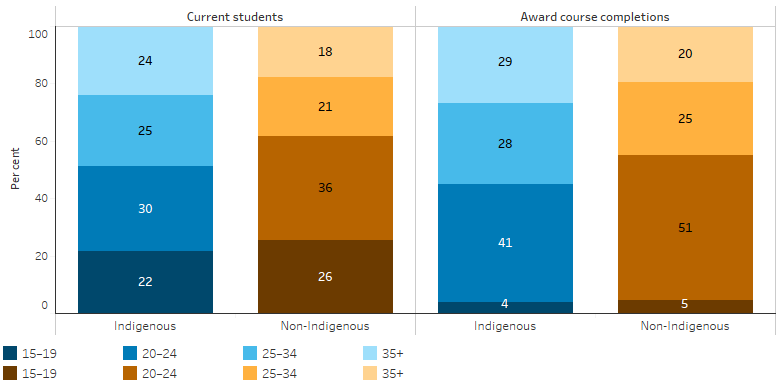

In 2018, 25% of Indigenous students were aged 25–34, and 24% were aged 35 and over, compared with 21% and 18% of non-Indigenous students. A similar age difference was also seen in course completions (Table D2.06.28, Figure 2.06.6).

Figure 2.06.6: Proportion of current higher education students and course completions in selected age ranges, by Indigenous status, 2018

Source: Table D2.06.28. AIHW analysis of Department of Education Higher Education Statistics Collection.

Benefits of attainment

In 2018–19, Indigenous Australians aged 15–64 who had a non-school qualification were more likely to be employed (61%) than those without a non-school qualification (38%) (Table D2.06.33).

In 2014–15, 53% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over reported that they intended to study in the future (Table D2.06.18). One-quarter (25%) said they had wanted to study in the past 12 months, but for various reasons had not. Of those who wanted to study but did not, just under 1 in 5 (19%) cited financial reasons, and under 1 in 6 (17%) cited personal or other family reasons (Table D2.06.19).

Comparisons with non-Indigenous Australians

Based on the 2021 ABS Census of Population and Housing, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over who were currently studying was similar to the proportion of non-Indigenous Australians who were currently studying (10% and 11% respectively) (Table D2.06.1).

However, levels of educational attainment are generally lower for Indigenous Australians than non-Indigenous Australians. In 2021, Year 12 or equivalent was the highest level of school completed for 40% of Indigenous adults, compared with 64% of non-Indigenous adults (Table D2.06.5).

Looking at non-school qualifications, in 2021, 48% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 reported they either completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above or were studying for a non-school qualification at any level – compared with 71% for non-Indigenous Australians. This gap was due to lower rates of attainment at Bachelor Degree and above, with 10% of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 having a Bachelor Degree or above, compared with 35% of non-Indigenous adults. The proportion of people aged 20–64 with a non-school qualification at Certificate III to Advanced Diploma level was slightly higher for Indigenous than non-Indigenous Australians (34% and 31% respectively) (Table D2.06.10).

In 2021, Indigenous Australians had a higher rate of VET attainment than non-Indigenous Australians, with 3.2% of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over completing a VET qualification in 2021, compared with 1.5% of non-Indigenous Australians (Table D2.06.17).

Change over time

Over the 3 Censuses from 2011 to 2021, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 18 and over who reported Year 12 or equivalent as their highest level of school completed increased: from 29% in 2011, to 35% in 2016 and to 40% in 2021 (Table D2.06.9). The proportion also increased for non-Indigenous Australians (from 55% to 64%), with minimal change in the rate difference (decrease from 26 to 24 percentage points) and rate ratio (increase from 0.5 to 0.6).

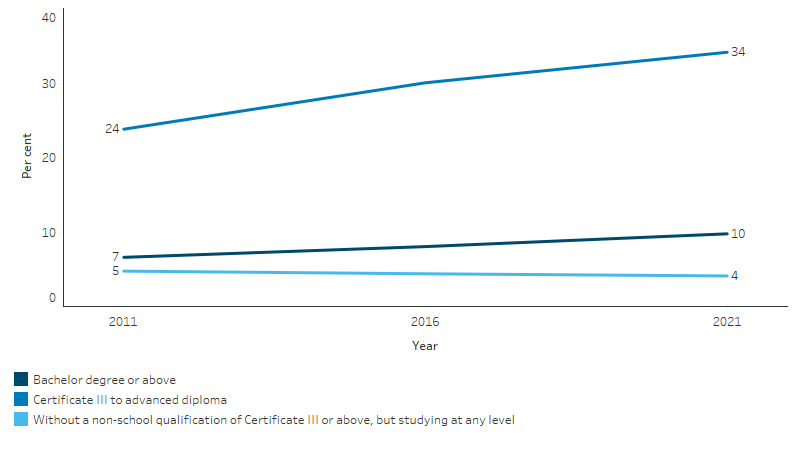

There have also been increases in the rate of non-school qualifications among Indigenous Australians. From 2011 to 2021, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 with a Certificate III to Advanced Diploma increased from 24% to 34%, and the proportion with a Bachelor Degree or above increased from 6.6% to 9.8% (Table D2.06.13, Figure 2.06.7).

Figure 2.06.7: Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 with a non–school qualification at Certificate III level or above and/or currently studying, by level of qualification, Australia, 2011, 2016 and 2021

Source: Table D2.06.13. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

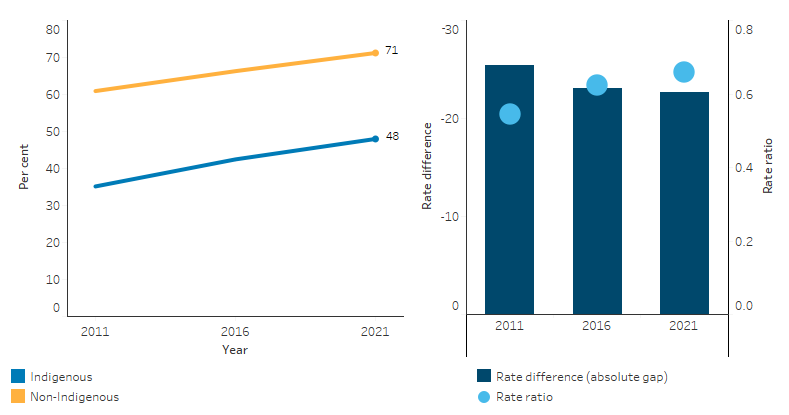

The proportion of Indigenous Australians who had completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above, and/or were currently studying for a non-school qualification at any level, increased from 35% in 2011, to 42% in 2016, and 48% in 2021 (Table D2.06.13, Figure 2.06.8). The proportion of non-Indigenous Australians who completed a non-school qualification at Certificate III or above, and/or were currently studying also increased (from 61% to 71%). The gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians decreased slightly between 2011 (rate difference of 26 percentage points) and 2021 (23 percentage points).

Figure 2.06.8: Proportion of people aged 20–64 with a non–school qualification at Certificate III level or above and/or were currently studying for a non-school qualification at any level, by Indigenous status and changes in the gap, Australia, 2011, 2016 and 2021

Notes

1. Non-school qualification at Certificate III or above includes those who are currently studying.

2. Rate difference is calculated as the rate for Indigenous Australians minus non-Indigenous Australians. The rate difference values are negative, reflecting a lower rate for Indigenous Australians.

Source: Table D2.06.13. AIHW analysis of ABS Census of Population and Housing (ABS 2022).

In the decade from 2012 and 2021, the proportion of Indigenous Australians aged 15 and over completing government funded VET qualifications decreased from 4.1% to 3.2% (Table D2.06.17, Figure 2.06.9). The proportion also decreased among non-Indigenous Australians, from 2.7% of those aged 15 and over in 2012, to 1.5% in 2021.

Figure 2.06.9: Proportion of people aged 15 and over who completed government-funded VET qualification/s in the year, by Indigenous status, 2012–2021

Source: Table D2.06.17. AIHW analysis of VOCSTATS (NCVER 2022).

The VET load pass rate is a way of calculating completion rates, and is the ratio of hours studied by students who passed their subject(s) to the total hours committed to by all students who passed, failed or withdrew from the corresponding subject(s) (Bedmarz 2012). In 2021, the overall VET load pass rate for Indigenous students aged 15–64 was 78%, an increase from 75% in 2012 (Table D2.06.30). For non-Indigenous students, there was no statistically significant change in VET load pass rate between 2012 and 2021, varying between 82% and 85% over this period.

Between 1996 and 2018, Indigenous students as a proportion of all domestic students rose from 1.2% to 1.8%—an increase of 38%.

The number of Indigenous students commencing in higher education more than doubled, from 3,624 students in 1996 to 7,273 students in 2018. The rate of commencing Indigenous students aged 20–64 increased by 37%, from 148 per 10,000 in 2001 to 170 per 10,000 in 2018.

The rate at which Indigenous Australians aged 20–64 completed higher education courses rose from 38 per 10,000 in 2001 to 67 per 10,000 in 2018, an increase of 68% (Table D2.06.25, Figure 2.06.10).

Figure 2.06.10: Higher education course completion rate (per 10,000), Indigenous Australians aged 25–64, 2001–2018

Source: Table D2.06.25. AIHW analysis of Department of Education Higher Education Statistics Collection.

Research and evaluation findings

Adults with higher educational attainment are likely to have better health and lifespans compared with their less educated peers. A study of the influence of education on health using an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015, highlighted that tertiary education is critical in influencing infant mortality, life expectancy, child vaccination, and enrolment rates. In addition, the study also found that with a rise of tertiary adult education level and tertiary enrolment rate, there is a decrease in both value and variation in potential years of life lost (premature mortality) (Raghupathi & Raghupathi 2020).

There is evidence that adult learning can increase skills, which in turn can lead to employment, promotions or wage increases. This can have flow-on benefits for physical and mental health, and the effects can be greater for more socially disadvantaged groups (Chandola et al. 2011; Institute of Health Equity 2014).

Research has identified some important factors for consideration in developing strategies to improve post-school education participation that reflect both academic performance and educational expectations of Indigenous young people.

Mahuteau and others (2015) found that if Indigenous and non-Indigenous students reach the same level of academic achievement by the time they are 15, there is no significant difference in subsequent educational outcomes, such as completing Year 12 and participating in university or vocational education and training (Mahuteau et al. 2015).

Research by Biddle and Cameron (2012) shows that differences in higher education participation may have compounded from differences in academic achievement at younger ages (Biddle & Cameron 2012). However, once Indigenous students received a tertiary admission rank, they were as likely as non-Indigenous students to go to university, albeit with lower tertiary admission scores (on average). Further research on understanding why Indigenous students have lower test scores in school would help direct policy attention to improving academic achievement throughout secondary education, which would lead to broader opportunities post-school (Biddle & Cameron 2012). (See measure 2.04 Literacy and numeracy).

Pathways from school to VET and from VET to university education are convoluted. VET can be seen as a pathway to higher education. However, because VET has a focus on skill development, whereas university has a greater focus on critical thinking, which is a different type of educational pursuit, this pathway may not necessarily be straightforward for students. Universities also need to be supportive enough for Indigenous students to be able to navigate and have the confidence to achieve and complete university education (Frawley et al. 2017). This requires addressing aspirations and achievement earlier in schooling to build self-efficacy among Indigenous students. Several Australian universities have programs with Indigenous Australian school students to build aspiration and highlight the opportunities higher education can offer.

A scoping review identified many barriers to pursuing and accessing higher education for Indigenous adults. A central theme was a lack of career guidance and knowledge about further education, and geographic location was identified as a physical barrier for Indigenous Australians from rural and remote areas (Gore et al. 2017b). Limited opportunities to participate in higher education on Country requires many Indigenous students wishing to further their education to relocate. A relatively high proportion of Indigenous university students come from regional and remote areas, and housing and relocation costs are often an additional burden. Students who relocate may experience further challenges such as isolation from being away from their families and communities (Behrendt et al. 2012; Gore et al. 2017b).

Data from a 2013 University Experience Survey found that, among Indigenous students who had seriously considered leaving university before graduating, financial difficulty was the most commonly reported reason (44%) (Edwards & McMillan 2015).

Noting a lack of high-quality, robust and comprehensive evaluations in Indigenous program and policy contexts across Australia in general, a recent report explored ways of strengthening evaluation in the Indigenous higher education context. The report identified 14 enablers and drivers that can strengthen evaluation in Indigenous higher education and explained how they intersect with three domains of control: Indigenous, government and university. Indigenous control (including Indigenous leadership, valuing Indigenous knowledge and sovereign rights), government control (including increasing funding and resources, leading innovative policy development) and university control (including investing in cultural transformation and improving Indigenous student outcomes) can interact to have a profound effect on evaluation within higher education contexts in Australia. The report presented 17 recommendations for strengthening evaluation in Indigenous higher education that cover research, policy and practice settings. The first recommendation is the prioritisation of ‘the development of a National Indigenous Higher Education Performance and Evaluation Strategy’ that is Indigenous-led and appropriately resourced (Smith et al. 2018).

A 2012 review examined the role of higher education in closing the gap and reducing Indigenous disadvantage. The review, focusing mainly on universities, found that Indigenous Australians are significantly under-represented in the higher education system and that this contributes to the social and economic disadvantage they experience. A range of sources (such as program-based monitoring data) were used to monitor progress and assess overall success; however, the review noted that there was a lack of independent evaluations to draw on. Consequently, a recommendation of the review was for the Australian Government to work with universities to develop a monitoring and evaluation framework for assessing progress in achieving outcomes for Indigenous Australians in higher education (Behrendt et al. 2012).

The review outlines some of the barriers that are preventing Indigenous Australians from achieving successful higher education outcomes, including low numbers of Indigenous students completing Year 12, a lack of awareness about how to transition, a lack of support from families and communities, and a lack of financial support and flexible work arrangements from government and employers. The review panel proposed a collaborative approach with universities, governments, communities and professional bodies working together to improve higher education outcomes for Indigenous Australians. Specific recommendations included that universities develop strategies to recruit and retain Indigenous staff; develop frameworks that reflect the inclusion of Indigenous knowledge within curriculums and teaching practices; and build stronger relationships with schools to better support Indigenous pathways (Behrendt et al. 2012).

The Wiyi Yani U Thangani (Women’s Voices) Securing Our Rights, Securing Our Future Report (Australian Human Rights Commission 2020) is the first national report in over 30 years where 2,300 First Nations women and girls have been heard as a collective on the issues that matter to them. A total of 106 face-to-face engagements were held across 50 communities in Australia, involving a total of in 2,294 women and girls. These consultations explored all aspects of First Nations women and girls’ experiences, including their strengths, challenges and aspirations for the future.

The Report identified the importance of education, training and employment as vehicles for First Nations women and girls to fully participate in all aspects of society. Barriers identified through the consultations as impeding access to education, training and pathways into employment included affordability, local availability, inadequate supports and lack of cultural representation and inclusivity. School-based engagement and mentoring programs were reported to foster a culturally safe and inclusive environment to increase access to education and training opportunities for First Nations women and girls.

A review of the literature found that academic self-concept, cultural connectedness, relationship networks, educational culture and teachers, and regionality influence Indigenous student aspiration and motivation (Bowra A et al. 2020). A study by Briggs demonstrated a need to provide alternative pathways such as TAFE to disengaged students (Briggs 2017). First Nations young people can favour the TAFE pathway for its perceived work opportunities and its practical training pathway (Gore et al. 2017a).

Implications

Concerted efforts to increase Year 12 attainment are positively contributing to increased numbers of Indigenous students enrolling in and completing higher education. However, significant numbers of Indigenous young people aged 15–24 are currently not engaged in further education, training or employment (see measure 2.07 Employment).

Understanding of pathways for Indigenous young people from school into employment would benefit from research using longitudinal data following individuals over time (Hunter 2010). Longitudinal data is needed to understand what specific interventions will encourage an Indigenous youth who would otherwise drop out of school or post-school study to attend and complete school (Biddle & Cameron 2012).

Indigenous Australians’ tertiary educational attainment remains lower than for non-Indigenous Australians. This increases with remoteness. Employment outcomes for Indigenous Australians tended to be much more linked to their education background compared to non-Indigenous Australians. This highlights the importance of accessible and targeted education pathways to improve Indigenous Australians’ employment outcomes. Indigenous Australians completing higher level qualifications (Certificate III and above) in high-demand fields are more likely to be employed in those fields. However, lower level qualifications in high demand fields (Certificate I or Certificate II) do not necessarily result in employment in those fields. For example, Indigenous Australians who studied information technology (IT) were unlikely to work in IT if they have only completed lower level qualifications in that field.

Access to education is life changing for many Indigenous Australians. However, Indigenous Australians do not access tertiary education at the same rate as non-Indigenous Australians. The tertiary education system needs to better engage with Indigenous Australians from remote areas. There is an increase in over-representation of young Indigenous Australians who are not fully engaged in post school education and/or training or employment as remoteness increases. The gap in employment outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians was widest in Remote and Very remote Australia. For example, only 30.2% of Indigenous young people are fully engaged with employment, training and education in Very remote areas compared with 81.7% for non-Indigenous young people (Productivity Commission 2023). Indigenous young people in remote areas are at risk of continuing long-term unemployment and long-term welfare dependency.

Research by the National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER) suggests that Indigenous students are more successful when they are taught by local trainers and are able to engage in their learning on country and in their own language (Guenther et al. 2017). This suggests that efforts to expand and grow the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Community-Controlled Registered Training Organisations (ACCRTOs) sector and other Indigenous organisations providing training and support services, will provide the cultural settings and learning styles needed to improve outcomes for First Nations people in the VET sector.

Tertiary education has an important role in achieving the Closing the Gap targets and priority reforms. The National Agreement on Closing the Gap Targets 6 and 7 relate directly to further education outcomes for First Nations Australians and both are not on track. There is urgent need for more to be done to bring these targets back on track.

Ensuring that young Indigenous Australians are supported throughout their secondary schooling to make successful post-school transitions is critical to improving their employment prospects and, subsequently, their health and other outcomes. The gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians in higher education is linked to factors such as the cost of higher education, non-completion of schooling, low academic achievement, expectations, motivations (Gale et al. 2010; Hunter 2010), and factors affecting educational choices (for example, access to information, educational aspirations, and awareness of how to transition) (Behrendt et al. 2012; Parker et al. 2013). These barriers, as well as those affecting retention and completion rates of Indigenous students in higher education, should inform policies and initiatives aimed at the increasing participation and attainment of Indigenous adults in higher education.

In line with recommendations of the 2012 Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, all Australian universities have strategies in place for improving Indigenous Australians’ access to, and outcomes from, higher education (Behrendt et al. 2012).

However, the lack of rigorous evaluation of efforts to improve educational participation means there is little robust evidence of what works.

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2022. 2021 Census - counting persons, place of usual residence [Census TableBuilder Pro product].

- ACSQHC (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care) 2013. Consumers, the health system and health literacy: taking action to improve safety and quality. Sydney: ACSQHC.

- Anderson I 2011. Indigenous pathways into the professions. Canberra: Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

- Australian Human Rights Commission 2020. Wiyi Yani U Thangani Report (2020).

- Bedmarz A 2012. Lifting the lid on completion rates in the VET sector: how they are defined and derived. (ed., Research NCfVE).

- Behrendt L, Larkin S, Griew R & Kelly P 2012. Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Final Report. Canberra: Department of Education and Training.

- Biddle N & Cameron T 2012. Potential Factors Influencing Indigenous Education Participation and Achievement. Research Report. National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER).

- Bowra A, Howard L, Mashford-pringle A & Di Ruggiero E 2020. Indigenous Cultural Safety Training in Health, Education, and Social Service Work. Social Science Protocols 3.

- Boyd H 1996. The determinants of Indigenous employment outcomes: the importance of education and training. Centre for Aboriginal Economic Policy Research (CAEPR), Australian National University.

- Briggs A 2017. Links Between Senior High School Indigenous Attendance, Retention and Engagement: Observations at Two Urban High Schools. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 46:34-43.

- Chandola T & Jenkins A 2014. The scope of adult and further education for reducing health inequalities. If you Could Do One Thing...82-90.

- Chandola T, Plewis I, Morris JM, Mishra G & Blane D 2011. Is adult education associated with reduced coronary heart disease risk? International journal of epidemiology 40:1499-509.

- Edwards D & McMillan J 2015. Completing university in a growing sector: Is equity an issue? Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research

- Frawley J, Smith JA, Gunstone A, Pechenkina E, Ludwig W & Stewart A 2017. Indigenous VET to Higher Education pathways and transitions: A literature review. International Studies in Widening Participation 4:34-54.

- Gale T, Hattam R, Comber B, Tranter D, Bills D, Sellar S et al. 2010. Interventions early in school as a means to improve higher education outcomes for disadvantaged students. National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education.

- Gore J, Holmes K, Smith M, Fray L, McElduff P, Weaver N et al. 2017a. Unpacking the career aspirations of Australian school students: towards an evidence base for university equity initiatives in schools. Higher Education Research & Development 36:1383-400.

- Gore J, Patfield S, Fray L, Holmes K, Gruppetta M, Lloyd A et al. 2017b. The participation of Australian Indigenous students in higher education: a scoping review of empirical research, 2000–2016. The Australian Educational Researcher 44:323-55.

- Guenther J, Bat M, Stephens A, Skewes J, Boughton B, Williamson F et al. 2017. Enhancing training advantage for remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander learners

- Hart MB, Moore MJ & Laverty M 2017. Improving Indigenous health through education. The Medical Journal of Australia 207:11-2.

- Hunter B 2010. Pathways for Indigenous school leavers to undertake training or gain employment. (ed., Australian Institute of Health and Welfare & Australian Institute of Family Studies). Canberra: Closing the Gap Clearinghouse.

- Institute of Health Equity 2014. Local action on health inequalities. London.

- Lamb S & McKenzie P 2001. Patterns of success and failure in the transition from school to work in Australia. ACER.

- Mahuteau S, Karmel T, Mavromaras K & Zhu R 2015. Educational Outcomes of Young Indigenous Australians. Adelaide: National Institute of Labour Studies.

- NCVER (National Centre for Vocational Education Research) 2022. Government-funded students and courses [VOCSTATS]. NCVER. Viewed 19 May 2023.

- Parker PD, Bodkin-Andrews G, Marsh HW, Jerrim J & Schoon I 2013. Will closing the achievement gap solve the problem? An analysis of primary and secondary effects for Indigenous university entry. Journal of Sociology 51:1085-102.

- Productivity Commission 2023. Closing the Gap Information Repository. Viewed 29 May 2023.

- Raghupathi V & Raghupathi W 2020. The influence of education on health: an empirical assessment of OECD countries for the period 1995–2015. Archives of Public Health 78:20.

- Schuller T 2017. What are the wider benefits of learning across the life course? (Foresight Future of Skills and Lifelong Learning Project). Government Office for Science.

- Smith J, Pollard K, Robertson K & Shalley F 2018. Strengthening Evaluation in Indigenous Higher Education Contexts in Australia: 2017 Equity Fellowship Report. Perth: National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education.