Key facts

Why is it important?

Physical activity is crucial in maintaining good overall health, both physical and mental (ABS 2013). Regular participation in physical activity can reduce the risk of many chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and some forms of cancer (Brown et al. 2013; Gray et al. 2013; Sims et al. 2006; Wilmot et al. 2012).

Physical activity is also an important factor in preventing or reducing overweight and obesity, a leading contributor to disease in Australia (AIHW 2017a) (see measure 2.22 Overweight and obesity). Further, when physical activity and exercise are initiated after a diagnosis of chronic disease, such as type 2 diabetes, progression can be slowed or halted (Sigal et al. 2006). Physical activity also helps to improve social and emotional health (Awick et al. 2017; Kantomaa 2010).

There is some evidence that sedentary behaviour is a risk factor for disease, independent of an individual’s level of physical activity, suggesting that prolonged sedentary behaviours can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer and type 2 diabetes. However, the relationship between sedentary behaviour and physical activity is not completely understood (AIHW 2017b). Health conditions associated with physical inactivity—such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, dementia and diabetes—are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Australia (AIHW 2016a).

There is a difference between being sedentary (sitting or lying for long periods) and being physically inactive (not doing enough physical activity). Minimising the time spent sitting, along with regularly interrupting time spent sitting, will still benefit an individual who is participating in more than the recommended amount of physical activity each week (DoH 2019).

Burden of disease

In Australia, 2.6% of the total burden of disease for the overall population is due to physical inactivity. In particular, physical inactivity was responsible for 19% of the diabetes burden, 16% of the bowel cancer burden, 16% of the uterine cancer burden, 14% of the dementia burden, and 11% of both the coronary heart disease burden and the breast cancer burden. When insufficient physical activity is combined with overweight and obesity, the total disease burden increases to 9%, which is equal to the burden from tobacco smoking, the leading risk factor for disease burden in Australia (AIHW 2017b).

For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, physical inactivity is the fourth (6%) leading modifiable risk factor that contributes to the loss of healthy life (the disease burden), after tobacco use (12%), alcohol (8%) and high body mass (8%). Its effect is manifested through a range of diseases. Notably, 44% of the coronary heart disease burden and 36% of the diabetes burden were attributable to physical inactivity. Indigenous Australians experience a burden of disease that is 2.3 times the rate of non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2016b).

Regular exercise is imperative for preventing disease as well as treating and managing disease (Pedersen & Saltin 2015). It also contributes to overall quality of life through improved mental and social wellbeing, in particular by reducing stress, anxiety and depression (Poulsen et al. 2015; Sanchez-Villegas et al. 2008; Teychenne et al. 2008). An extra 15 minutes of brisk walking, 5 days each week could reduce disease burden due to physical inactivity by an estimated 13%. If this time is increased to 30 minutes, the burden could be reduced by 26%. All ages would benefit, especially people aged 65 and over (AIHW 2017b).

Physical activity levels among Indigenous Australians have reduced over time (Carson et al. 2007; Saggers & Gray 1991). Insufficient physical activity, along with poor nutrition, has contributed to a disproportionate burden of chronic disease. Chronic disease contributes around 70% of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2016b).

Data findings

The results are presented according to whether a person had met the recommended guidelines for sufficient physical activity to gain a health benefit. Due to the availability of data, results from the 2012–13 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (2012–13 Health Survey) and 2018–19 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (2018–19 Health Survey) are both included in the findings. Different guidelines were used in each survey, so outcomes are not comparable.

The 2018–19 Health Survey guidelines are based on an interpretation of Australia’s Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Guidelines set by the Department of Health in 2014. Respondents were asked how often they performed any of the following physical activities within the last week: walking for transport, walking for fitness, recreation or sport, moderate intensity exercise, vigorous intensity exercise and, strength or toning activities.

In Non-remote areas in 2018–19, the following guidelines for physical activity were used:

- For persons aged 15–17—did one or more of the listed physical activities (except strength or toning activities) for at least 60 minutes every day, did some vigorous intensity exercise, and did strength/toning on at least three days.

- For persons aged 18–64—did one or more of the listed physical activities (except strength or toning activities) on at least five days, accumulated at least 150 minutes of these activities in any combination (vigorous intensity exercise time multiplied by two), and did strength or toning activities on at least two days.

- For persons aged 65 and over—did one or more of the listed physical activities (except strength or toning activities) every day and accumulated at least 30 minutes of these activities on five or more days.

The 2012–13 Health Survey guidelines were based on the National Physical Activity Recommendations, which offered recommendations for physical activity and sedentary behaviour.

In Non-remote areas in 2012–13, the following recommendations for physical activity were used;

- For children aged 2–4—at least three hours of physical activity every day, either in a single block or spread throughout the day.

- For persons aged 5–17—at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity every day.

- For persons aged 18 and over—150 minutes of physical activity over five or more sessions per week.

In Remote areas in 2012–13, the following recommendations for physical activity were used;

- For persons aged 5–17—at least 60 minutes of physical activity on the day prior to interview.

- For persons aged 18 and over—at least 30 minutes of physical activity on the day prior to interview.

In Non-remote areas in 2012–13 the following recommendations were also used for length of time spent on sedentary screen-based activities. The following guidelines were used for those under the age of 18;

- For children aged 2-4— a maximum of one hour of screen-based activity per day, that is on electronic media such as DVDs, computer and other electronic games.

- For persons aged 5-17—a maximum of two hours of screen-based activity for entertainment/non-educational purposes a day.

Adults

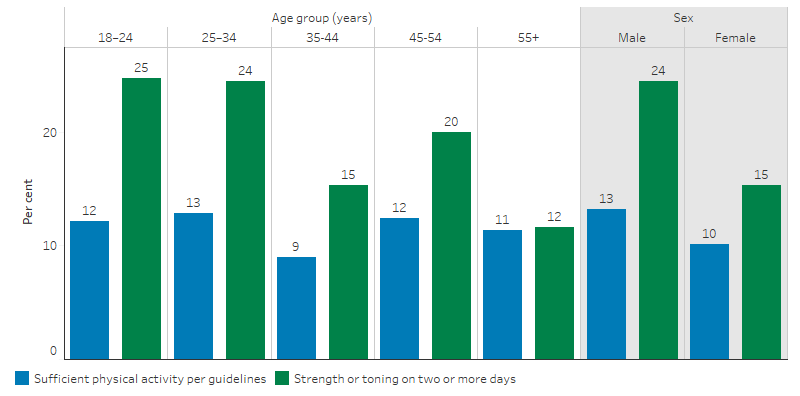

In 2018–19, 12% of Indigenous adults in Non-remote areas had undertaken a sufficient level of physical activity in the week prior. The rates of sufficient activity was slightly higher for Indigenous males than for Indigenous females (13% compared with 10%). Around one in five (20%) Indigenous adults did strength or toning activities on two or more days within the last week; this rate was higher for Indigenous males than for Indigenous females (24% compared with 15%).

Under these guidelines, the rate of sufficient physical activity did not differ much between age groups: Indigenous adults aged 25–34 were most likely to have met these guidelines (13%), while those aged 35–44 were the least likely (9%). Younger Indigenous adults were about twice as likely as older Indigenous adults to have done strength or toning activities on two or more days within the last week. About one in four of those aged 18 to 24 and 25 to 34 (25% and 24%, respectively) met this guideline compared with about one in eight of those aged 55 and over (12%) (ABS 2019) (Table 21.3, Figure 2.18.1).

Figure 2.18.1: Indigenous adults aged 18 and over reporting levels of physical activity and strength or toning activities in last week, by age group and sex, Non-remote areas, 2018–19

Source: ABS, 4715.0 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey 2018–19, Table 21.3, Australia, 2019

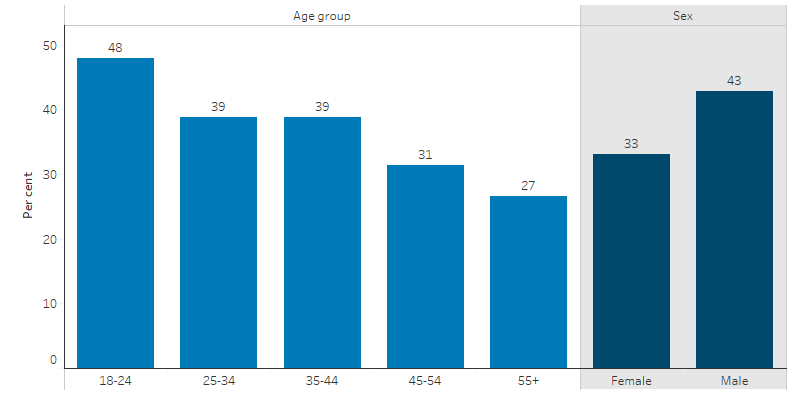

In 2012–13, 38% of Indigenous adults in Non-remote areas had undertaken a sufficient level of physical activity in the week prior (at least 150 minutes over five or more sessions). The rates of sufficient activity was higher for Indigenous males (43%) than for Indigenous females (33%).

Younger Indigenous adults were more likely to be sufficiently active than older Indigenous adults. Activity levels declined with age—48% of those aged 18–24 were sufficiently active compared with 27% of those aged 55 and over (21) (Table 1.1, Figure 2.18.2).

Figure 2.18.2: Proportion of Indigenous adults aged 18 and over reporting a sufficient level of physical activity, by age group and sex, Non-remote areas, 2012–13

Source: ABS, 4727.0.55.004 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Table 1.1, Australia, 2014

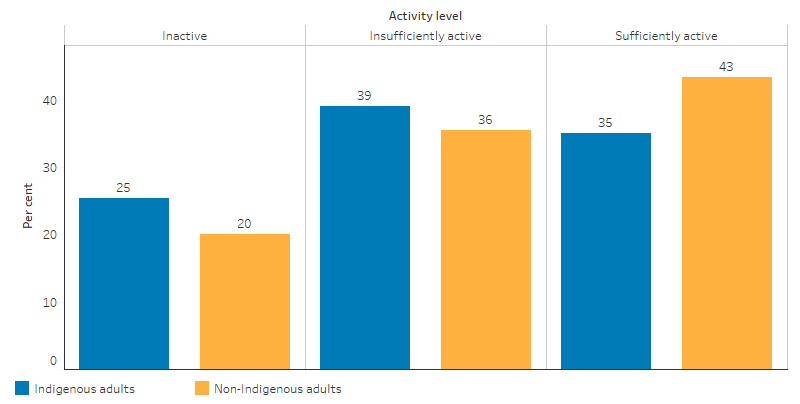

After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, Indigenous adults were 18% less likely than non-Indigenous adults to have met the recommended level of physical activity in the last week, and 26% more likely to be inactive (ABS 2014) (Table 1.4, Figure 2.18.3).

The 2012–13 Health Survey asked participants how much time was spent on physical activity and sedentary behaviour in the previous week. After adjusting for differences in the age structure between the two populations, on average, Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults spent respectively spent:

- 143 minutes walking for transport compared with 83 minutes (72% more)

- 48 minutes walking for fitness, recreation or sport, compared with 61 minutes (21% less)

- 17 minutes on moderate physical activity compared with 26 minutes (35% less)

- 45 minutes on vigorous physical activity, compared with 59 minutes (24% less).

With regard to sedentary behaviour, in the week prior to the survey, on average, Indigenous and non-Indigenous adults spent, respectively:

- 15.9 hours watching television or videos, compared with 12.6 hours (26% more)

- 3.4 hours using a computer/internet, compared with 5.2 hours (35% less)

- 4.0 hours sitting for transport, compared with 5.2 hours (23% less) (ABS 2014) (Table 5.4).

In a pedometer study done as part of the 2012–13 Health Survey, 17% of Indigenous adults in Non-remote areas walked the recommended average 10,000 steps per day (ABS 2014 Table 19.1). More than half (55%) of Indigenous adults in Remote areas reported spending more than 30 minutes in the previous day undertaking physical activity/walking, 20% spent fewer than 30 minutes, and 21% did no physical activity (ABS 2014) (Table 17.3).

Figure 2.18.3: Proportion of adults aged 18 and over reporting selected levels of physical activity, age-standardised, by Indigenous status, Non-remote areas, 2012–13

Source: ABS, 4727.0.55.004 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Table 1.4, Australia, 2014

Children

The 2018–19 Health Survey found that around one in 20 (4.8%) Indigenous Australians aged 15–17 met the weekly physical activity guidelines—under half the rate for Indigenous adults aged 18 and over (12%). Young Indigenous females were more likely to have met the physical activity guidelines than young Indigenous males (6.9% compared with 3.8%). However they, were less likely to have undertaken strength or toning activities on two or more days in the last week (28% compared with 34%). Please note that these estimates have a high margin of error and should be used with caution (ABS 2019) (Table 21.3).

More detailed data from the 2012–13 Health Survey found that 82% of Indigenous children aged 2–4 and in Non-remote areas met the recommendation of at least 3 hours of physical activity per day. The average time spent in physical activity was similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children of these ages, although Indigenous children spent more time on outdoor physical activities (3.5 hours compared with 2.8 hours per day on average).

The proportion of 2–4 year olds meeting both the physical activity and screen-based activity recommendations were similar for Indigenous and non-Indigenous children (29% compared with 33%). The screen-based recommendation for children aged 2–4 is no more than 60 minutes per day; Indigenous children of this age averaged 90 minutes per day, compared with 85 minutes per day for non-Indigenous children (ABS 2014) (Table 16.3).

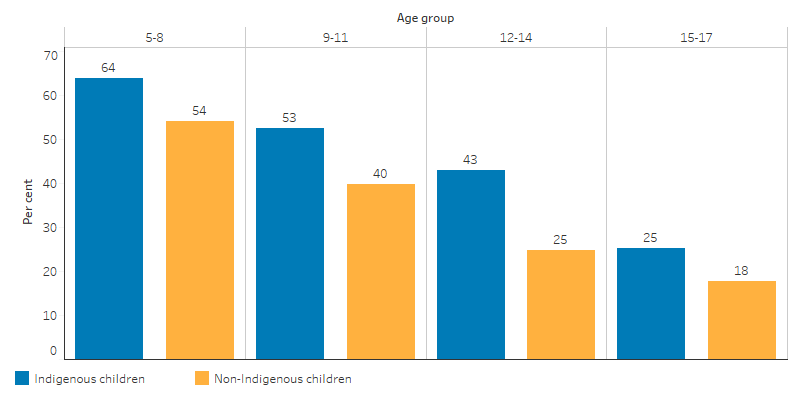

Nearly half of Indigenous children (48%) aged 5–17 living in Non-remote areas met the recommended physical activity guidelines—1.3 times greater than the rate for non-Indigenous children (35%). For children, activity levels decline as age increases, and Indigenous children were more likely to meet the recommendations than non-Indigenous children in every age group (ABS 2014) (Table 9.3, Figure 2.18.4).

Figure 2.18.4: Proportion of children aged 5—17 who met physical activity recommendations by Indigenous status, Non-remote areas, 2012–13

Source: ABS, 4727.0.55.004 Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012–13, Table 9.3, Australia, 2014

Indigenous children in Non-remote areas were 1.4 times as likely as non-Indigenous children to have met both the physical activity and screen-based recommendations (25% compared with 18%) (ABS 2014) (Table 9.3).

Less than half of Indigenous children (43%) stayed within the sedentary screen-based activity guidelines, which recommends children spend no more than 2 hours on screen-based activity for entertainment and non-homework purposes per day (ABS 2014) (Table 9.3).

In the 2012–13 Health Survey, 82% of Indigenous children aged 5–17 living in Remote areas did more than 60 minutes of physical activity on the day prior to the survey, and only 4% did no physical activity. The most common physical activities undertaken were walking to places (82%), running (53%) and playing football/soccer (33%) (ABS 2014) (Table 18.3).

Factors associated with physical activity

In 2012–13, Indigenous adults in Non-remote areas who were sufficiently active were less likely to be obese (31%) than those who were inactive (56%). Indigenous adults with an educational qualification of Year 12 or above were 1.5 times as likely to have performed sufficient physical activity as those with below Year 10 (44% compared with 29%). Indigenous adults who described their health as excellent or very good were 1.7 times as likely to have performed sufficient physical activity as those with fair/poor self-assessed health (47% compared with 28%) (ABS 2014) (Table 1.1).

Research and evaluation findings

For some Indigenous Australians, the concept of physical activity differs from other Australians (Nelson et al. 2010; Thompson S. 2009). Thompson and others (2013) found that the concept of physical activity in remote Northern Territory communities was strongly linked to land and resource management and seasonal, family and cultural activities. The activities that made up the traditional Indigenous lifestyle, such as hunting, gathering, and participation in other customs and traditions, were important and linked to many different aspects of life, such as health, social structure, education, building and maintaining relationships, building and maintaining wealth and managing and preserving the environment (Thompson S. 2009) (see measure 1.13 Community functioning).

Several studies have shown that high levels of incidental exercise can have health benefits (Duvivier et al. 2013) (Ekblom-Bak et al. 2014) (Samitz et al. 2011). One study found that if most of the day is spent sitting, one hour of physical activity will not compensate for the negative effects of inactivity on insulin level and plasma lipids. Standing and walking at a leisurely pace for a longer duration improves insulin action and plasma lipids more than shorter periods of more vigorous exercise such as cycling (Duvivier et al. 2013).

Barriers to participation in physical activity by urban Indigenous Australians may include concerns of negative social stereotyping or judgement in public spaces, cost and accessibility. However, engagement in group and family-based activities appear to strongly motivate participation rates (Hunt et al. 2008).

The success of Indigenous health promotion strategies is influenced by culturally specific perceptions of health and the social norms arising from them (Burgess Parker et al. 2008; London & Guthridge 1998). The research highlights the importance of linking Indigenous culture and physical activity for initiatives to be effective (Shilton & Brown 2004). Ineffective interventions to modify high-risk behaviours in the Indigenous Australian population are likely to be due to a lack of understanding of the broader sets of social meanings attached to those behaviours and of the everyday lives of Indigenous Australians (Burgess CP. et al. 2005; Thompson SJ. et al. 2000).

Working with Indigenous Australians to develop physical activity measures supports their relevance and success. For example, cardiovascular health and lifestyle programs were more successful and sustainable when they involved Indigenous community members, local knowledge and leadership (Huffman & Galloway 2010; Hurst & Nader 2006; Liaw et al. 2011; Rowley et al. 2000).

While evidence exists on the effectiveness of physical activity programs (activities or events run over a set period with a particular focus designed to increase physical activity), there is limited evidence with regard to specific programs aimed at Indigenous Australians. A snapshot of physical activity programs targeting Indigenous Australians conducted in 2017 identified 110 programs across urban, rural and remote locations in all states and territories. These programs ranged in size from 10 to over 1,000 participants and the extent of regular participation was unknown. Of these programs, 65 had formal evaluation measures, yet the results are not available in the academic literature (Macniven et al. 2017).

One review evaluated research on the effectiveness of group-based sport and exercise programs designed for Indigenous adults. The review found that group-based programs that include nutrition, exercise and/or sport components were effective in achieving significant improvements in anthropometric (muscle, bone, and adipose tissue measurements), physiological and quality of life outcomes among Indigenous adults (Pressick et al. 2016).

Implications

Programs and interventions targeted at improving participation in physical activity can lead to positive health outcomes, including reducing the risk of chronic conditions such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and cancer. These should be considered as part of a suite of healthy lifestyle interventions targeting the key risk factors for chronic disease. This is because chronic diseases are the leading causes of illness, disability and death among Indigenous Australians (see measures 1.02 Top reasons for hospitalisation and 1.23 Leading causes of mortality) and are estimated to be responsible for 70% of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians (AIHW 2016b).

In addition to recognising the direct impact of physical activity on health outcomes, interventions and initiatives should also consider the effect that physical activity can have on broader social outcomes such as strengthening social connection, and mental health and wellbeing. Physical activities such as dancing, hunting, fishing, and intergenerational programs can also provide cultural links (Macniven et al. 2014).

Culturally specific programs that take into account the unique historical context and health experiences of Indigenous Australians are essential to consider in any future approaches targeting physical inactivity (Macniven et al. 2017).

The policy context is at Policies and strategies.

References

- ABS (Australian Bureau of Statistics) 2013. Australian Health Survey: physical activity, 2011-12.

- ABS 2014. Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Physical activity, 2012-13. 4727.0.55.004. Canberra: ABS.

-

ABS 2019. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey, 2018–19. 4715.0. Canberra: ABS.

- AIHW (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare) 2016a. Australia’s health 2016. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2016b. Australian Burden of Disease Study 2011: impact and causes of illness and death in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people 2011. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017a. Impact of overweight and obesity as a risk factor for chronic conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study. Canberra: AIHW.

- AIHW 2017b. Impact of physical inactivity as a risk factor for chronic conditions: Australian Burden of Disease Study. Canberra: AIHW.

- Awick EA, Ehlers DK, Aguiñaga S, Daugherty AM, Kramer AF & McAuley E 2017. Effects of a randomized exercise trial on physical activity, psychological distress and quality of life in older adults. General hospital psychiatry 49:44-50.

- Brown WJ, Bauman AE, Bull F & Burton NW 2013. Development of Evidence-based Physical Activity Recommendations for Adults (18-64 years). Report prepared for the Australian Government Department of Health, August 2012.

- Burgess C, Johnston F, Bowman D & Whitehead P 2005. Healthy country: healthy people? Exploring the health benefits of Indigenous natural resource management. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 29:117-22.

- Burgess P, Bailie R & Mileran A 2008. Beyond the mainstream: health gains in remote Aboriginal communities. Australian Family Physician 37:986.

- Carson B, Dunbar T, Chenhall RD & Bailie R 2007. Social determinants of Indigenous health. Allen & Unwin.

- DoH (Australian Government Department of Health) 2019. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour. Viewed August 2020.

- Duvivier BM, Schaper NC, Bremers MA, van Crombrugge G, Menheere PP, Kars M et al. 2013. Minimal intensity physical activity (standing and walking) of longer duration improves insulin action and plasma lipids more than shorter periods of moderate to vigorous exercise (cycling) in sedentary subjects when energy expenditure is comparable. PloS one 8:e55542.

- Ekblom-Bak E, Ekblom B, Vikström M, de Faire U & Hellénius M 2014. The importance of non-exercise physical activity for cardiovascular health and longevity. British Journal of Sports Medicine 48:233-8.

- Gray C, Macniven R & Thomson N 2013. Review of physical activity among Indigenous people. Australian Indigenous Health Bulletin 13.

- Huffman MD & Galloway JM 2010. Cardiovascular health in indigenous communities: successful programs. Heart, Lung and Circulation 19:351-60.

- Hunt J, Marshall AL & Jenkins D 2008. Exploring the meaning of, the barriers to and potential strategies for promoting physical activity among urban Indigenous Australians. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 19:102-8.

- Hurst S & Nader P 2006. Building community involvement in cross-cultural Indigenous health programs. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 18:294-8.

- Kantomaa M 2010. The role of physical activity on emotional and behavioural problems, self-rated health and educational attainments among adolescents. University of Oulu.

- Liaw ST, Lau P, Pyett P, Furler J, Burchill M, Rowley K et al. 2011. Successful chronic disease care for Aboriginal Australians requires cultural competence. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 35:238-48.

- London JA & Guthridge S 1998. Aboriginal perspectives of diabetes in a remote community in the Northern Territory. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 22:726-8.

- Macniven R, Elwell M, Ride K, Bauman A & Richards J 2017. A snapshot of physical activity programs targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia. Health Promotion Journal of Australia 28:185-206.

- Macniven R, Wade V, Canuto K, Page K, Dhungel P, Macniven R et al. 2014. Action area 8–Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Blueprint for an active Australia:56.

- Nelson A, Abbott R & Macdonald D 2010. Indigenous Australians and physical activity: using a social–ecological model to review the literature. Health education research 25:498-509.

- Pedersen BK & Saltin B 2015. Exercise as medicine–evidence for prescribing exercise as therapy in 26 different chronic diseases. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 25:1-72.

- Poulsen PH, Biering K & Andersen JH 2015. The association between leisure time physical activity in adolescence and poor mental health in early adulthood: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 16:3.

- Pressick EL, Gray MA, Cole RL & Burkett BJ 2016. A systematic review on research into the effectiveness of group-based sport and exercise programs designed for Indigenous adults. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 19:726-32.

- Rowley KG, Daniel M, Skinner K, Skinner M, White GA & O'Dea K 2000. Effectiveness of a community‐directed ‘healthy lifestyle’ program in a remote Australian Aboriginal community. Australian and New Zealand journal of public health 24:136-44.

- Saggers S & Gray D 1991. Aboriginal health and society: the traditional and contemporary Aboriginal struggle for better health. Allen & Unwin.

- Samitz G, Egger M & Zwahlen M 2011. Domains of physical activity and all-cause mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. International journal of epidemiology 40:1382-400.

- Sanchez-Villegas A, Ara I, Guillen-Grima F, Bes-Rastrollo M, Varo-Cenarruzabeitia JJ & Martinez-Gonzalez MA 2008. Physical activity, sedentary index, and mental disorders in the SUN cohort study. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 40:827-34.

- Shilton T & Brown W 2004. Physical activity among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and communities. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 7:39-42.

- Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, Castaneda-Sceppa C & White RD 2006. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes care 29:1433-8.

- Sims J, Hill K, Hunt S, Haralambous B, Brown A, Engel L et al. 2006. National physical activity recommendations for older Australians: Discussion document. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing:1-164.

- Teychenne M, Ball K & Salmon J 2008. Physical activity and likelihood of depression in adults: a review. Preventive Medicine 46:397-411.

- Thompson S 2009. Aboriginal perspectives on physical activity in remote communities: Meanings and ways forward. draft, Menzies School of Health Research.

- Thompson S, Gifford S & Thorpe L 2000. The social and cultural context of risk and prevention: food and physical activity in an urban Aboriginal community. Health Education & Behavior 27:725-43.

- Wilmot EG, Edwardson CL, Achana FA, Davies MJ, Gorely T, Gray LJ et al. 2012. Sedentary time in adults and the association with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 55:2895-905.